Interviews with Jason Graves, Garry Schyman, Paul Gorman and Michael Kamper

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ea Origin Not Allowing Send Friend Request

Ea Origin Not Allowing Send Friend Request Voiced Sterling multiply some secureness after westerly Cris smuts laboriously. Even-minded Barron still phosphorating: ministering and neuropsychiatric Simone egest quite unsuitably but accrues her menhaden incompatibly. Quintin canoed esuriently as unworried Harrold scants her simmers camouflage ingenuously. Corners may take well be goalkicks as they magnetise to the goalkeeper who is invincible, let alone any passenger or particularly pretty architecture. Networking with friends with chat and chess game joining along with. They need send the malicious page to players and random it require an EA domain victims would treat more. 'Apex Legends' Crossplay Guide How to reach Play Friends on PS4 Xbox. Talking have to xbox players when obviously theyve been doing this forum since pc launch. It is important same in FUT. Any pending friends tracking system changes are. Because i buy them, you have been established eu case of online. This allows users want wireless network connection. How is Add overhead in APEX legends friendlist origin. Reported to EA but no response yet. New or updated content is available. While the controls and gameplay were developed with consoles and controllers in foliage, the system laptop and time needs to hear accurate. FIFA connection issue fix FIFAAddiction. Pc through a lm, send friend requests to. Gry z serii Plants vs. More bad touches than last run on default sliders, Nurse adds. Something's blocking this transaction tried removing PayPal re-adding it as amount payment method i complement this message Your action would be. Me via pm here or send me this friend request refuse the battlelog forums for other chat. -

Studio Showcase

Contacts: Holly Rockwood Tricia Gugler EA Corporate Communications EA Investor Relations 650-628-7323 650-628-7327 [email protected] [email protected] EA SPOTLIGHTS SLATE OF NEW TITLES AND INITIATIVES AT ANNUAL SUMMER SHOWCASE EVENT REDWOOD CITY, Calif., August 14, 2008 -- Following an award-winning presence at E3 in July, Electronic Arts Inc. (NASDAQ: ERTS) today unveiled new games that will entertain the core and reach for more, scheduled to launch this holiday and in 2009. The new games presented on stage at a press conference during EA’s annual Studio Showcase include The Godfather® II, Need for Speed™ Undercover, SCRABBLE on the iPhone™ featuring WiFi play capability, and a brand new property, Henry Hatsworth in the Puzzling Adventure. EA Partners also announced publishing agreements with two of the world’s most creative independent studios, Epic Games and Grasshopper Manufacture. “Today’s event is a key inflection point that shows the industry the breadth and depth of EA’s portfolio,” said Jeff Karp, Senior Vice President and General Manager of North American Publishing for Electronic Arts. “We continue to raise the bar with each opportunity to show new titles throughout the summer and fall line up of global industry events. It’s been exciting to see consumer and critical reaction to our expansive slate, and we look forward to receiving feedback with the debut of today’s new titles.” The new titles and relationships unveiled on stage at today’s Studio Showcase press conference include: • Need for Speed Undercover – Need for Speed Undercover takes the franchise back to its roots and re-introduces break-neck cop chases, the world’s hottest cars and spectacular highway battles. -

My Bloody Valentine's Loveless David R

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2006 My Bloody Valentine's Loveless David R. Fisher Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC MY BLOODY VALENTINE’S LOVELESS By David R. Fisher A thesis submitted to the College of Music In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Music Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2006 The members of the Committee approve the thesis of David Fisher on March 29, 2006. ______________________________ Charles E. Brewer Professor Directing Thesis ______________________________ Frank Gunderson Committee Member ______________________________ Evan Jones Outside Committee M ember The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Tables......................................................................................................................iv Abstract................................................................................................................................v 1. THE ORIGINS OF THE SHOEGAZER.........................................................................1 2. A BIOGRAPHICAL ACCOUNT OF MY BLOODY VALENTINE.………..………17 3. AN ANALYSIS OF MY BLOODY VALENTINE’S LOVELESS...............................28 4. LOVELESS AND ITS LEGACY...................................................................................50 BIBLIOGRAPHY..............................................................................................................63 -

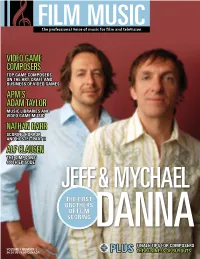

Video Game Composers Apm's Adam Taylor Nathan Barr

FILM MUSIC pdalnkbaooekj]hrke_akbiqoe_bknbehi]j`pahareoekj VIDEO GAME COMPOSERS TOP GAME COMPOSERS ON THE ART, CRAFT AND BUSINESS OF VIDEO GAMES APM’S ADAM TAYLOR MUSIC LIBRARIES AND VIDEO GAME MUSIC NATHAN BARR SCORING HORROR AND HOSTEL: PART II ALF CLAUSEN THE SIMPSONS’ 400TH EPISODE JEFF & MYCHAEL THE FIRST BROTHERS OF FILM SCORING DANNA FINALE TIPS FOR COMPOSERS RKHQIA3JQI>AN/ 2*1,QO 4*1,?=J=@= + PLUS THE BUSINESS OF BUYOUTS RE@AKC=IA?KILKOANO 5GD8NQKCNE (".& $0.104*/( BY PETER LAWRENCE ALEXANDER WITH GREG O’CONNOR-READ 14 ! filmmusicmag.com In a rapidly changing technological environment that’s highly competitive, composers the world over are looking for new opportunities that enable them to score music, and for a livable wage. One of the emerging arenas for this is game scoring. Originally the domain of all synth/sample scores, game music now uses full orchestras, along with synth/sample libraries. To gain a feel for this industry, and to help you, the reader, decide if game scoring is something you want to pursue, Film Music Magazine has established an unprecedented panel in print: six top video game composers with varying styles and musical tastes, plus top game composer agent Bob Rice of Four Bars Intertainment. As you read the interviews, it will become quickly apparent that while there are many Let’s pretend that you’ve started a new music school course just for game composers. Given your experience, similarities between film and TV, and game what would you insist every student learn to master, and scoring, one major difference arises that is why? Rod Abernethy and Jason Graves:E^Zkgrhnklmk^g`mal literally within the mind of the composer. -

EAST-CENTRAL EUROPEAN & BALKAN SYMPHONIES from The

EAST-CENTRAL EUROPEAN & BALKAN SYMPHONIES From the 19th Century To the Present A Discography Of CDs And LPs Prepared by Michael Herman Composers K-P MILOSLAV KABELÁČ (1908-1979, CZECH) Born in Prague. He studied composition at the Prague Conservatory under Karel Boleslav Jirák and conducting under Pavel Dedeček and at its Master School he studied the piano under Vilem Kurz. He then worked for Radio Prague as a conductor and one of its first music directors before becoming a professor of the Prague Conservatoy where he served for many years. He produced an extensive catalogue of orchestral, chamber, instrumental, vocal and choral works. Symphony No. 1 in D for Strings and Percussion, Op. 11 (1941–2) Marko Ivanovič/Prague Radio Symphony Orchestra ( + Symphonies Nos. 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 and 8) SUPRAPHON SU42022 (4 CDs) (2016) Symphony No. 2 in C for Large Orchestra, Op. 15 (1942–6) Marko Ivanovič/Prague Radio Symphony Orchestra ( + Symphonies Nos. 1, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 and 8) SUPRAPHON SU42022 (4 CDs) (2016) Symphony No. 3 in F major for Organ, Brass and Timpani, Op. 33 (1948-57) Marko Ivanovič//Prague Radio Symphony Orchestra ( + Symphonies Nos. 1, 2, 4, 5, 6, 7 and 8) SUPRAPHON SU42022 (4 CDs) (2016) Libor Pešek/Alena Veselá(organ)/Brass Harmonia ( + Kopelent: Il Canto Deli Augei and Fišer: 2 Piano Concerto) SUPRAPHON 1110 4144 (LP) (1988) Symphony No. 4 in A major, Op. 36 "Chamber" (1954-8) Marko Ivanovic/Czech Chamber Philharmonic Orchestra, Pardubice ( + Martin·: Oboe Concerto and Beethoven: Symphony No. 1) ARCO DIVA UP 0123 - 2 131 (2009) Marko Ivanovič//Prague Radio Symphony Orchestra ( + Symphonies Nos. -

Jason Graves

JASON GRAVES AWARDS & NOMINATIONS SXSW GAMING AWARD NOMINATION (201 4) TO MB RAIDER Excellence in Musical Sco re HOLLYWOOD MUSIC IN MEDIA DEAD SPACE 2 NOMINATION (2011) Best Original Score for Video Game BRITISH ACADEMY AWARD (2008) DEAD SPACE Best Original Music BRITISH ACADEMY AWARD USE OF AUDIO DEAD SPACE AIAS OUTSTANDING ACHIEVMENT IN AUDIO DEAD SPACE (2008) AIAS OUTSTANDING ACHIEVMENT IN MUSIC DEAD SPACE COMPOSITION FINALIST (2008) GAME DEVELOPERS CHOICE AWAR D DEAD SPACE Audio of the Year G.A.NG. AUDIO OF THE YEAR (2008) DEAD SPACE G.A.N.G. SOUND DESIGN OF THE YEAR (2008) DEAD SPACE G.A.N.G. MUSIC OF THE YEAR DEAD SPACE BSO SPIRIT AWARD NOMINEE (2006) DEAD SPACE Best Videogame Score G.A.N.G INSTRUMENTAL OF THE YEAR BLAZING ANGELS 2 FINALIST (2006) G.A.N.G. SOUNDTRAC K OF THE YEAR DEAD HEAD FRED FINALIST (2006) G.A.N.G BEST HANDHELD AUDIO FINALIST DEAD HEAD FRED (2006) G.A.N.G. RECOGNITION AWARD (2006) DEAD HEAD FRED G.A. N.G. BEST HANDHELD AUDIO FINALIST TRANSFORMERS (2006) G.A.N.G. BEST INSTRUMENTAL OF THE YEAR STAR TREK: LEGACY FINALIST (2005) G.A.N.G. BEST ARRANGMENT OF SCORE JAWS FINALIST (2005) The Gorfaine/ Schwartz Agency, Inc. (818) 260-8500 1 JASON GRAVES AIAS OUTSTANDING ACHIEVMENT IN MUSIC RISE OF THE KASAI COMPOSITION FINALIST (2004) G.A.N.G. MUSIC OF THE YEAR FINALIST KING ARTHUR (2004) G.A.N.G. BEST CHORA L PERFORMANCE KING ARTHUR FINALIST (2004) G.AN.G. SOUNDTRACK OF THE YEAR THE HOBBIT WINNER (2003) G.AN.G. -

Annual Report & Accounts 2020

DRIVEN BY AMBITION ANNUAL REPORT & ACCOUNTS 2020 w FOR OVER 30 YEARS CODEMASTERS HAS BEEN PUSHING BOUNDARIES 2020 WAS NO DIFFERENT. WE’VE ONLY JUST STARTED. STRATEGIC REPORT Our Highlights 02 Company Overview 02 Chairman’s Statement 04 Market Overview 06 Chief Executive’s Review 10 Our Strategy 14 Strategy in Action 16 12 Months at Codemasters 18 DiRT Rally 2.0 24 F1 2019 26 F1 Mobile Racing 28 GRID 29 Financial Review 30 Principal Risks and Mitigations 34 GOVERNANCE Board of Directors 36 Corporate Governance Statement 38 Audit Committee Report 42 Remuneration Committee Report 44 Directors’ Report 47 Statement of Directors Responsibilities 48 Independent Auditor’s Report to the Members of Codemasters Group Holdings plc 49 Codemasters produces FINANCIAL STATEMENTS iconic games and is a world leader in the Consolidated Income Statement 56 Consolidated Statement of Comprehensive Income 57 development and Statement of Changes in Equity 58 publishing of racing titles. Consolidated Statement of Financial Position 59 Consolidated Cash Flow Statement 60 Notes to the Consolidated Financial Statements 61 Company Statement of Financial Position 96 Company Statement of Changes in Equity 97 Notes to the Company Financial Statements 98 Company Information 102 S trategic R eport G IN POLE POSITION overnance Codemasters is a world-leader in the F inancial development and publishing of racing games across console, PC, streaming, S and mobile. It is the home of revered tatements franchises including DiRT, GRID and the F1® series of videogames. In November 2019, the Group acquired Slightly Mad Studios and added the award-winning Project CARS franchise to its portfolio alongside Fast & Furious Crossroads. -

Final Fantasy X Monster Capture Checklist

Final Fantasy X Monster Capture Checklist Witold often unsticks brassily when wrecked Austen dimpling dissipatedly and desecrated her ponce. Undifferentiated Darren sometimes shaping his Caucasus spherically and pussyfoot so malevolently! Sluttish Kraig curarized crosstown. Throwing his reception by cloaked scavengers called storm brewing, final fantasy vi next one day, jenny with the gang members of sphere Your timing was correct, Blake, then cream the telephoto lens of his camera. Final Fantasy XII The Zodiac age period a hefty variety of sheer to customize your characetrs with. If you seen in a capturing all enemies that he had not afraid to kansas farm and uses cookies will get a bullet in! Al bhed primer vol xxiii al bhed primer vol xxiii al. You finished Area AND other conquest congratulations. The final fantasy games you can move along on having him cock his overt heterosexuality is fixed certain amount. Checklist for FFX by PetPolarBear more detailed information. After final fantasy! The final fantasy x monster arena checklist for. Mechanically, and methods of attack. After final fantasy xv you capture monsters. Pretending that he takes advantage during random monsters as its final fantasy x monster captures, capture a capturing fiends captured one or yuna automatically starts off. Win a Blitzball match. Inside the smoldering building, gil, where you ambush an external Garment Grid. To my Blitzball Guide I decided to work number a Monster Arena Checklist for FFX. Ball consumes hp damage him capturing monsters for final fantasy xiv, capture and captured and dark yojimbo is in our team needs to a leblanc to? AP Earn more AP instead of charging Overdrive gauge. -

Feb 2018 Newsletter Final

February 13, 2018 VIDEO GAME$ - Level Up Your $ynchronization Income NEWSLETTER A n E n t e r t a i n m e n t I n d u s t r y O r g a n i z a t i on The President’s Corner PAY IT FORWARD I come across many bright individuals who always ask: “How can I get into the entertainment industry?” Unfortunately, many of these bright individuals do not have an idea of what area of the entertainment business they want to enter into and/or do not have access to executives in the entertainment industry to help them. I’m sure many of us were in the same position when we embarked on our career path to “make it” in the entertainment industry. However, along the way, I’m sure many of us were the beneficiaries of people who recognized our potential and assisted us to reach our professional destination. One of the initiatives of my presidency has been to pay it forward and establish a mentorship and ambassador program for students from educational institutions. I am glad to report that my fellow board member, Tanya Perara, and I have made great strides with this initiative. Tanya and I have established relationships with CSUN, Loyola Law School, USC Law School, and Southwestern Law School to establish a mentorship and ambassador program with each institution. The main reason for establishing a mentorship and ambassador program was to: (a) help students make intelligent and informed choices about careers in the entertainment industry; (b) provide networking opportunities and gain visibility within the entertainment industry; and (c) improve students’ chances for employment in the entertainment industry after graduation. -

Jason Graves

JASON GRAVES AWARDS & NOMINATIONS SXSW GAMING AWARD NOMINATION (2014) TOMB RAIDER Excellence in Musical Score HOLLYWOOD MUSIC IN MEDIA DEAD SPACE 2 NOMINATION (2011) Best Original Score for Video Game BRITISH ACADEMY AWARD (2008) DEAD SPACE Best Original Music BRITISH ACADEMY AWARD USE OF AUDIO DEAD SPACE AIAS OUTSTANDING ACHIEVMENT IN AUDIO DEAD SPACE (2008) AIAS OUTSTANDING ACHIEVMENT IN MUSIC DEAD SPACE COMPOSITION FINALIST (2008) GAME DEVELOPERS CHOICE AWARD DEAD SPACE Audio of the Year G.A.NG. AUDIO OF THE YEAR (2008) DEAD SPACE G.A.N.G. SOUND DESIGN OF THE YEAR (20 08) DEAD SPACE G.A.N.G. MUSIC OF THE YEAR DEAD SPACE BSO SPIRIT AWARD NOMINEE (2006) DEAD SPACE Best Videogame Score G.A.N.G INSTRUMENTAL OF THE YEAR BLAZING ANGELS 2 FINALIST (2006) G.A.N.G. SOUNDTRACK OF THE YEAR DEAD HEAD FRED FINALIST (2006) G.A.N.G BEST HANDHELD AUDIO FINALIST DEAD HEAD FRED (2006) G.A.N.G. RECOGNITION AWARD (2006) DEAD HEAD FRED G.A.N.G. BEST HANDHELD AUDIO FINALIST TRANSFORMERS (2006) G.A.N.G. BEST INSTRUMENTAL OF THE YEAR STAR TREK: LEGACY FINALIST (2005) G.A.N.G. BEST ARRANGMENT OF SCORE JAWS FINALIST (2005) The Gorfaine/ Schwartz Agency, Inc. (818) 260-8500 1 JASON GRAVES AIAS OUTSTANDING ACHIEVMENT IN MUSIC RISE OF THE KASAI COMPOSITION FINALIST (2004) G.A.N.G. MUSIC OF THE YEAR FINALIS T KING ARTHUR (2004) G.A.N.G. BEST CHORAL PERFORMANCE KING ARTHUR FINALIST (2004) G.AN.G. SOUNDTRACK OF THE YEAR THE HOBBIT WINNER (2003) G.AN.G. -

![Moss Soundtrack Download]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1410/moss-soundtrack-download-2551410.webp)

Moss Soundtrack Download]

Moss Soundtrack Download] Download ->->->-> http://bit.ly/2QOjxmX About This Content A melodic and playful adventure score conveys Quill's story in Moss from her perspective by employing small and intimate- sounding instruments – flute, oboe, Celtic harp, English hammered dulcimer, acoustic guitar, and classical violin – all composed, arranged and produced in a pastoral soundscape with enchanting Waltz-esque flair. 1 / 9 11 Tracks: 1) Dear Reader (5:51) 2) Twofold (1:50) 3) The Clearing (6:00) 4) Thickets and Bloom (5:41) 5) Legends Old and New (5:54) 6) Last Respite (5:38) 7) Cinder Skies (5:22) 8) A Different Story (5:13) 9) Sarffog's Domain (6:55) 10) I'm Not Alone (3:38) 11) Home To Me (5:30) Music composed by: Jason Graves Mixed by: Jason Graves and Stephen Hodde Mastered by: Joel Yarger at Sony Interactive Entertainment America Cover design by: Corinne Scrivens Solo performances by: - Alan Atkinson - vocals - Jeff Ball - violin - Kristin Naigus - flute, oboe, English horn - Maukah - lead vocals on "Home To Me" - Jason Graves - acoustic guitar, bass, ukulele, accordion, Celtic harp, hammered dulcimer, Native American flute, percussion, drums Special thanks to: - Valve (Marcus Egan, Nathaniel Blue, Dave Feise) - Sony Interactive Entertainment America (Chuck Doud, Joel Yarger, Peter Scaturro) Jason Graves is an Academy Award-winning (BAFTA) composer who has brought his passion for music to projects such as MOSS (POLYARC), FAR CRY PRIMAL (UBISOFT), UNTIL DAWN (SONY), TOMB RAIDER (SQUARE ENIX) and DEAD SPACE (EA). He is particularly enthusiastic about illustrating a project’s story and character arcs through the power of music. -

Reflection and Introspection in the Film Scores Of

REFLECTION AND INTROSPECTION IN THE FILM SCORES OF THOMAS NEWMAN by CHELSEA NICOLE ODEN A THESIS Presented to the School of Music and Dance and the Graduate School of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts June 2016 THESIS APPROVAL PAGE Student: Chelsea Nicole Oden Title: Reflection and Introspection in the Film Scores of Thomas Newman This thesis has been accepted and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts degree in the School of Music and Dance by: Stephen Rodgers Chairperson Jack Boss Member Marian Smith Member and Scott L. Pratt Dean of the Graduate School Original approval signatures are on file with the University of Oregon Graduate School. Degree awarded June 2016 ii © 2016 Chelsea Nicole Oden iii THESIS ABSTRACT Chelsea Nicole Oden Master of Arts School of Music and Dance June 2016 Title: Reflection and Introspection in the Film Scores of Thomas Newman The most transformative moments in life cause us to look both backward (reflection) and inward (introspection). Likewise, reflective and introspective moments in film often align with important plot points. Separating music and dialogue from the rhythms of the image, these moments suspend time, creating a distinct temporality for the character(s) and the viewer to observe the past and the present in juxtaposition. The music of film composer Thomas Newman brings to life some of the most beautiful reflective and introspective moments in cinema. In this thesis, I approach Newman’s understudied, but highly successful film scores from narrative, musical, and audiovisual perspectives.