Lynching, Federalism, and the Intersection of Race and Gender in the Progressive Era

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dealing with Jim Crow

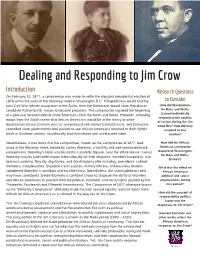

Dealing and Responding to Jim Crow Introduction Research Questions On February 26, 1877, a compromise was made to settle the disputed presidential election of 1876 within the walls of the Wormley Hotel in Washington D.C. If Republicans would end the to Consider post-Civil War military occupation of the South, then the Democrats would allow Republican How did Washington, candidate Rutherford B. Hayes to become president. The compromise signaled the beginning Du Bois, and Wells- of a post-war reconciliation of white Americans from the North and South. However, removing Barnett individually respond to the conflict troops from the South meant that African Americans would be at the mercy of white of racism during the Jim Southerners (many of whom were or sympathized with former Confederates), and Democrat- Crow Era? How did they controlled state governments who wanted to see African Americans returned to their rightful respond to one place in Southern society, as politically disenfranchised and uneducated labor. another? Nevertheless, it was ironic that the compromise, known as the Compromise of 1877, took How did the African place at the Wormley Hotel, owned by James Wormley, a wealthy and well-connected black American community entrepreneur. Wormley’s Hotel was located in Layafette Square, near the White House. James respond to Washington, Du Bois and Wells- Wormley and his hotel were known internationally for their elegance, excellent hospitality, and Barnett? delicious catering. Royalty, dignitaries, and Washington’s elite including: presidents, cabinet members, Congressmen, Supreme Court justices, military officers, and business leaders What was the effect on considered Wormley a confidant and excellent host. -

Mobb Deep Reveal Tracklist for the Black Cocaine EP Featuresnas

Mobb Deep Reveal Tracklist For “The Black Cocaine” EP, Features Nas ERROR_GETTING_IMAGES-1 Mobb Deep Reveal Tracklist For “The Black Cocaine” EP, Features Nas 1 / 4 2 / 4 See separate feature article on page three for more on the ... country club feature. 60 Rider ... ing call for the show's 27th season outside of Tommy Doyle's in ... albums that any hip-hop fan must ... “Mobb Deep : The Black Cocaine. EP.” The album will be released on ... cord with Nas making a guest appear-.. Eight tracks deep, Lil' Fame and Billy Danze are sporting their usual energetic ... The EP was released shortly before their third album, "First Family 4 Life", ... Exactly one month from today, Mobb Deep will be releasing their first project ... and guest features and production from the usual suspects like Nas, ... Plus, it's a soundtrack, and hip-hop soundtracks have a history of mediocrity. ... Drumma Boy-produced album opener “Smokin On” featuring Juicy J sets the ... The classic status of Mobb Deep's The Infamous is undisputed: It's a seminal ... If the Black Cocaine EP released last week is any indication, the .... ... -show-featuring-rockie-fresh-julian-malone-harry-fraud-plastician- and-more-video/ ... http://www.jayforce.com/rb/vinyl-destination-ep-19-vancouver-canada-thats-a-wrap- ... 0.2 http://www.jayforce.com/music/dj-spintelect-the-best-of-nas-mixtape/ ... .jayforce.com/videos/mobb-deep-20th-anniversary- show-in-chicago-video/ .... Mobb Deep Reveal Tracklist For "The Black Cocaine" EP, Features Nas. 169. Mobb Deep has announced an upcoming EP to be released on ... -

Race, Rape And, Media Portrayals of the Central Park Jogger Case

Bard College Bard Digital Commons Senior Projects Spring 2016 Bard Undergraduate Senior Projects Spring 2016 Saintly Victim(s), Savage Assailants: Race, Rape and, Media Portrayals of the Central Park Jogger Case Thomas Palacios Beddall Bard College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.bard.edu/senproj_s2016 Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Beddall, Thomas Palacios, "Saintly Victim(s), Savage Assailants: Race, Rape and, Media Portrayals of the Central Park Jogger Case" (2016). Senior Projects Spring 2016. 194. https://digitalcommons.bard.edu/senproj_s2016/194 This Open Access work is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been provided to you by Bard College's Stevenson Library with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this work in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights- holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Saintly Victim(s), Savage Assailants: Race, Rape and, Media Portrayals of the Central Park Jogger Case Senior Project Submitted to The Division of Languages and Literature of Bard College by Thomas Palacios Beddall Annandale-on-Hudson, New York May 2016 Acknowledgements Thank you to my advisor -

The Brute Caricature

The Brute Caricature MORE PICTURES The brute caricature portrays black men as innately savage, animalistic, destructive, and criminal -- deserving punishment, maybe death. This brute is a fiend, a sociopath, an anti-social menace. Black brutes are depicted as hideous, terrifying predators who target helpless victims, especially white women. Charles H. Smith (1893), writing in the 1890s, claimed, "A bad negro is the most horrible creature upon the earth, the most brutal and merciless"(p. 181). Clifton R. Breckinridge (1900), a contemporary of Smith's, said of the black race, "when it produces a brute, he is the worst and most insatiate brute that exists in human form" (p. 174). George T. Winston (1901), another "Negrophobic" writer, claimed: When a knock is heard at the door [a White woman] shudders with nameless horror. The black brute is lurking in the dark, a monstrous beast, crazed with lust. His ferocity is almost demoniacal. A mad bull or tiger could scarcely be more brutal. A whole community is frenzied with horror, with the blind and furious rage for vengeance.(pp. 108-109) During slavery the dominant caricatures of blacks -- Mammy, Coon, Tom, and picaninny -- portrayed them as childlike, ignorant, docile, groveling, and generally harmless. These portrayals were pragmatic and instrumental. Proponents of slavery created and promoted images of blacks that justified slavery and soothed white consciences. If slaves were childlike, for example, then a paternalistic institution where masters acted as quasi-parents to their slaves was humane, even morally right. More importantly, slaves were rarely depicted as brutes because that portrayal might have become a self-fulfilling prophecy. -

Supplement to the City Record the Council —Stated Meeting of Thursday, March 25, 2010

SUPPLEMENT TO THE CITY RECORD THE COUNCIL —STATED MEETING OF THURSDAY, MARCH 25, 2010 The Invocation was delivered by Rev. Princess Thorbs, Assisting Minister, New THE COUNCIL Jerusalem Baptist Church, 122-05 Smith Street, Jamaica, New York, 11433. Minutes of the Let us pray. STATED MEETING Gracious God, God of Abraham, Isaac and Jacob, of We thank You, God, for another day. Thursday, March 25, 2010, 2:50 p.m. Now Lord, we ask that You would enter into this chamber. We welcome you, Father The President Pro Tempore (Council Member Rivera) that you would allow Your anointing Acting Presiding Officer and Your wisdom to be upon Your people. God bless those with Your wisdom Council Members that are going to be ruling over Your people. Give them your divine guidance according to Your will. Christine C. Quinn, Speaker Amen. Maria del Carmen Arroyo Vincent J. Gentile James S. Oddo Charles Barron Daniel J. Halloran III Annabel Palma Council Member Comrie moved to spread the Invocation in full upon the Record. Gale A. Brewer Vincent M. Ignizio Domenic M. Recchia, Jr. Fernando Cabrera Robert Jackson Joel Rivera Margaret S. Chin Letitia James Ydanis A. Rodriguez At a later point in the Meeting, the Speaker (Council Member Quinn) Leroy G. Comrie, Jr. Peter A. Koo Deborah L. Rose acknowledged the presence of former Council Member David Yassky and Council Member-elect David Greenfield (44th Council District, Brooklyn) in the Chambers. Elizabeth S. Crowley G. Oliver Koppell James Sanders, Jr. Inez E. Dickens Karen Koslowitz Larry B. Seabrook ADOPTION OF MINUTES Erik Martin Dilan Bradford S. -

The Strange Fruit of American Political Development

Politics, Groups, and Identities ISSN: 2156-5503 (Print) 2156-5511 (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rpgi20 The Strange Fruit of American Political Development Megan Ming Francis To cite this article: Megan Ming Francis (2018) The Strange Fruit of American Political Development, Politics, Groups, and Identities, 6:1, 128-137, DOI: 10.1080/21565503.2017.1420551 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/21565503.2017.1420551 Published online: 12 Jan 2018. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 3185 View related articles View Crossmark data Citing articles: 3 View citing articles Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rpgi20 POLITICS, GROUPS, AND IDENTITIES, 2018 VOL. 6, NO. 1, 128–137 https://doi.org/10.1080/21565503.2017.1420551 DIALOGUE: AMERICAN POLITICAL DEVELOPMENT IN THE ERA OF BLACK LIVES MATTER The Strange Fruit of American Political Development Megan Ming Francis Department of Political Science, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA ABSTRACT ARTICLE HISTORY What is the relationship between black social movements, state Received 18 December 2017 violence, and political development in the United States? Today, Accepted 19 December 2017 this question is especially important given the staggering number KEYWORDS of unarmed black women and men who have been killed by the American Political police. In this article, I explore the degree to which American Development; black politics; Political Development (APD) scholarship has underestimated the civil rights; law; social role of social movements to shift political and constitutional movements; Black Lives development. I then argue that studying APD through the lens of Matter Black Lives Matter highlights the need for a sustained engagement with state violence and social movements in analyses of political and constitutional development. -

Cassociation^ of Southern Women for the "Prevention of Cynching ******

cAssociation^ of Southern Women for the "Prevention of Cynching JESSIE DANIEL AMES, EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR MRS. ATTWOOD MARTIN MRS. W. A. NEWELL CHAIRMAN 703 STANDARD BUILDING SECRETARY-TREASURER Louisville, Ky. Greensboro, n. c. EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE cAtlanta, Qa MRS. J. R. CAIN, COLUMBIA, S. C. MRS. GEORGE DAVIS, ORANGEBURG, S. C. MRS. M. E. TILLY, ATLANTA, GA. MRS. W. A. TURNER, ATLANTA, GA. MRS. E. MARVIN UNDERWOOD, ATLANTA, GA. January 7, 1932 Composite Picture of Lynching and Lynchers "Vuithout exception, every lynching is an exhibition of cowardice and cruelty. 11 Atlanta Constitution, January 16, 1931. "The falsity of the lynchers' pretense that he is the guardian of chastity." Macon News, November 14, 1930. "The lyncher is in very truth the most vicious debaucher of spirit ual values." Birmingham Age Herald, November 14, 1930. "Certainly th: atrocious barbarities of the mob do not enhance the security of women." Charleston, S. C. Evening lost. "Hunt down a member of a lynching mob and he will usually be found hiding behind a woman's skirt." Christian Century, January 8, 1931. ****** In the year 1930, Texas and Georgia, were black spots on the map. This year, 1931, those two states cleaned up and came thro with "no lynchings." But honors arc even. Two states, Louisiana and Tennessee, with "no lynchings" in 1930, add one each in 1931. Florida and Mississippi were the only two states having lynchings in both years. Five of the eight in the South were in these two States alone. Jessie Daniel limes Executive Director Association of Southern Women for the Prevention of Lynching CENTRAL COUNCIL Representatives at Large Mrs. -

Re-Presenting Black Masculinities in Ta-Nehisi Coates's

Re-Presenting Black Masculinities in Ta-Nehisi Coates’s Between the World and Me by Asmaa Aaouinti-Haris B.A. (Universitat de Barcelona) 2016 THESIS/CAPSTONE Submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in HUMANITIES in the GRADUATE SCHOOL of HOOD COLLEGE April 2018 Accepted: ________________________ ________________________ Amy Gottfried, Ph.D. Corey Campion, Ph.D. Committee Member Program Advisor ________________________ Terry Anne Scott, Ph.D. Committee Member ________________________ April M. Boulton, Ph.D. Dean of the Graduate School ________________________ Hoda Zaki, Ph.D. Capstone Advisor STATEMENT OF USE AND COPYRIGHT WAIVER I do authorize Hood College to lend this Thesis (Capstone), or reproductions of it, in total or in part, at the request of other institutions or individuals for the purpose of scholarly research. ii CONTENTS STATEMENT OF USE AND COPYRIGHT WAIVER…………………………….ii ABSTRACT ...............................................................................................................iv DEDICATION………………………………………………………………………..v ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS……………………………………………………….....vi Chapter 1: Introduction…………………………………………………………….…2 Chapter 2: Black Male Stereotypes…………………………………………………12 Chapter 3: Boyhood…………………………………………………………………26 Chapter 4: Fatherhood……………………………………………………………....44 Chapter 5: Conclusion…………………………………………………………...….63 WORKS CITED…………………………………………………………………….69 iii ABSTRACT Ta-Nehisi Coates’s memoir and letter to his son Between the World and Me (2015)—published shortly after the emergence of the Black Lives Matter movement—provides a rich and diverse representation of African American male life which is closely connected with contemporary United States society. This study explores how Coates represents and explains black manhood as well as how he defines his own identity as being excluded from United States society, yet as being central to the nation. Coates’s definition of masculinity is analyzed by focusing on his representations of boyhood and fatherhood. -

The Transition of Black One-Dimensional Characters from Film to Video Games

Southern Illinois University Carbondale OpenSIUC Research Papers Graduate School Spring 2016 The ewN Black Face: The rT ansition of Black One- Dimensional Characters from Film to Video Games Kyle A. Harris Southern Illinois University Carbondale, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/gs_rp Recommended Citation Harris, Kyle A. "The eN w Black Face: The rT ansition of Black One-Dimensional Characters from Film to Video Games." (Spring 2016). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at OpenSIUC. It has been accepted for inclusion in Research Papers by an authorized administrator of OpenSIUC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE NEW BLACK FACE: THE TRANSITION OF BLACK ONE-DIMENSIONAL CHARACTERS FROM FILM TO VIDEO GAMES By Kyle A. Harris B.A., Southern Illinois University, 2013 A Research Paper Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Master of Science Department of Mass Communications and Media Arts in the Graduate School Southern Illinois University Carbondale May 2016 RESEARCH PAPER APPROVAL THE NEW BLACK FACE: THE TRANSITION OF BLACK ONE-DIMENSIONAL CHARACTERS FROM FILM TO VIDEO GAMES By Kyle A. Harris A Research Paper Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in the field of Professional Media, Media Management Approved by: Dr. William Novotny Lawrence Department of Mass Communications and Media Arts In the Graduate School Southern Illinois University Carbondale -

African American Contributions to the American Film Industry”

Curriculum Units by Fellows of the Yale-New Haven Teachers Institute 1996 Volume III: Race and Representation in American Cinema In Their Own Words: African American Contributions to the American Film Industry” Curriculum Unit 96.03.14 by Gerene Freeman I believe it is safe to say that a large majority of my high school students are avid movie-goers. Most of them, if not all have a VCR in their homes. Amazingly many students are quite sagacious concerning matters pertaining to the blaxploitation films generated in the Sixties. Few, however, realize that African American involvement in film making had its inception as early as 1913. Through this curriculum unit it is my intention to provide high school students, at Cooperative High School for the Arts and Humanities, with an overview of two African American filmmakers and their contributions to film. Oscar Micheaux will be utilized as an example of African American contributions made to the silent era by African American pioneers in the film industry. Matty Rich will be used as an example of contemporary contributions. I have decided to look at Matty Rich as opposed to Spike Lee, John Singleton and/or Julie Dash for very specific reasons. First because he was so close to the age (18) many of my high school students are now when he made his first movie Straight Out of Brooklyn. Secondly, he emerged from an environment similar to that in which many of my student find themselves. Lastly, I believe he could represent for my students a reason to believe it is very possible for them to accomplish the same thing. -

ABSTRACT “The Good Angel of Practical Fraternity:” the Ku Klux Klan in Mclennan County, 1915-1924. Richard H. Fair, M.A. Me

ABSTRACT “The Good Angel of Practical Fraternity:” The Ku Klux Klan in McLennan County, 1915-1924. Richard H. Fair, M.A. Mentor: T. Michael Parrish, Ph.D. This thesis examines the culture of McLennan County surrounding the rise of the Ku Klux Klan in the 1920s and its influence in central Texas. The pervasive violent nature of the area, specifically cases of lynching, allowed the Klan to return. Championing the ideals of the Reconstruction era Klan and the “Lost Cause” mentality of the Confederacy, the 1920s Klan incorporated a Protestant religious fundamentalism into their principles, along with nationalism and white supremacy. After gaining influence in McLennan County, Klansmen began participating in politics to further advance their interests. The disastrous 1922 Waco Agreement, concerning the election of a Texas Senator, and Felix D. Robertson’s gubernatorial campaign in 1924 represent the Klan’s first and last attempts to manipulate politics. These failed endeavors marked the Klan’s decline in McLennan County and Texas at large. “The Good Angel of Practical Fraternity:” The Ku Klux Klan in McLennan County, 1915-1924 by Richard H. Fair, B.A. A Thesis Approved by the Department of History ___________________________________ Jeffrey S. Hamilton, Ph.D., Chairperson Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Baylor University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Approved by the Thesis Committee ___________________________________ T. Michael Parrish, Ph.D., Chairperson ___________________________________ Thomas L. Charlton, Ph.D. ___________________________________ Stephen M. Sloan, Ph.D. ___________________________________ Jerold L. Waltman, Ph.D. Accepted by the Graduate School August 2009 ___________________________________ J. -

AN ANALYSIS of the MUSICAL INTERPRETATIONS of NINA SIMONE by JESSIE L. FREYERMUTH B.M., Kansas State University, 2008 a THESIS S

AN ANALYSIS OF THE MUSICAL INTERPRETATIONS OF NINA SIMONE by JESSIE L. FREYERMUTH B.M., Kansas State University, 2008 A THESIS submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree MASTER OF MUSIC Department of Music College of Arts and Sciences KANSAS STATE UNIVERSITY Manhattan, Kansas 2010 Approved by: Major Professor Dale Ganz Copyright JESSIE L. FREYERMUTH 2010 Abstract Nina Simone was a prominent jazz musician of the late 1950s and 60s. Beyond her fame as a jazz musician, Nina Simone reached even greater status as a civil rights activist. Her music spoke to the hearts of hundreds of thousands in the black community who were struggling to rise above their status as a second-class citizen. Simone’s powerful anthems were a reminder that change was going to come. Nina Simone’s musical interpretation and approach was very unique because of her background as a classical pianist. Nina’s untrained vocal chops were a perfect blend of rough growl and smooth straight-tone, which provided an unquestionable feeling of heartache to the songs in her repertoire. Simone also had a knack for word painting, and the emotional climax in her songs is absolutely stunning. Nina Simone did not have a typical jazz style. Critics often described her as a “jazz-and-something-else-singer.” She moved effortlessly through genres, including gospel, blues, jazz, folk, classical, and even European classical. Probably her biggest mark, however, was on the genre of protest songs. Simone was one of the most outspoken and influential musicians throughout the civil rights movement. Her music spoke to the hundreds of thousands of African American men and women fighting for their rights during the 1960s.