All in Good Time Their Inside Operations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Type II Familial Synpolydactyly: Report on Two Families with an Emphasis on Variations of Expression

European Journal of Human Genetics (2011) 19, 112–114 & 2011 Macmillan Publishers Limited All rights reserved 1018-4813/11 www.nature.com/ejhg SHORT REPORT Type II familial synpolydactyly: report on two families with an emphasis on variations of expression Mohammad M Al-Qattan*,1 Type II familial synpolydactyly is rare and is known to have variable expression. However, no previous papers have attempted to review these variations. The aim of this paper was to review these variations and show several of these variable expressions in two families. The classic features of type II familial synpolydactyly are bilateral synpolydactyly of the third web spaces of the hands and bilateral synpolydactyly of the fourth web spaces of the feet. Several members of the two families reported in this paper showed the following variations: the third web spaces of the hands showing syndactyly without the polydactyly, normal feet, concurrent polydactyly of the little finger, concurrent clinodactyly of the little finger and the ‘homozygous’ phenotype. It was concluded that variable expressions of type II familial synpolydactyly are common and awareness of such variations is important to clinicians. European Journal of Human Genetics (2011) 19, 112–114; doi:10.1038/ejhg.2010.127; published online 18 August 2010 Keywords: type II familial syndactyly; inherited synpolydactyly; variations of expression INTRODUCTION CASE REPORTS Type II familial synpolydactyly is rare and it has been reported in o30 The first family families.1–12 It is characterized by bilateral synpolydactyly of the third The family had a history of synpolydactyly type II for several web spaces of the hands and bilateral synpolydactyly of the fourth web generations on the mother’s side (Table 1). -

TS4002 Wireless Synchronized Analog Clock Is Designed with an Easy-To-Read Dial Face, Durable Cherry Finished Wood Frame and Tamper-Proof Glass Lens

TS4002 - Wireless Synchronized Analog Clock The TS4002 Wireless Synchronized Analog Clock is designed with an easy-to-read dial face, durable cherry finished wood frame and tamper-proof glass lens. The TS4002 receives a wireless time signal transmitted daily by a main wireless paging controller, such as the VS4800. The TS4002 uses the time signal to automatically adjust itself, if necessary, to ensure accurate and synchronized time throughout the entire facility. The TS4002 does not require any wiring and is ideal for renovation projects and new installations. The TS4002 has a traditional look that matches a wide variety of applications and provides years of maintenance-free service. Key Features: • Viewing Distance of 50' • Automatic Daylight Saving Time Adjustment • Glass Lens • Quick Correction for Time Change (1-3 Minutes) • Flush Mount (Does Not Require Back Box) • Battery Operated (Optional AC Power Adaptor) • Customized Logo Option Options, Accessories and Complementary Products: Part Number Description TS-OPT-003 24-Hour Clock Face TS-OPT-004 Customized Analog Clock Face TS-OPT-005 Sealed Analog Clock TS-OPT-007 110 V AC Adaptor (Replaces Original Clock Batteries, Requires 1.5" Minimum Recessed Power Outlet) TS-OPT-011 Red Second Hand Specifications: Dimensions 19.5" x 8.5" x 2.05" (W x H x D) Dial Face 8", White Weight 5.25 lbs. Frequency VHF (148 - 174 MHz), UHF (400 - 470 MHz) Power Two AA Sized Batteries Paging Format POCSAG, Narrow Band Operating Temperature 32º - 120ºF Synchronization 1 Time/Day (Optional 6 Times/Day, User Selectable) Humidity 0% - 95%, Non-Condensing Receiver Sensitivity 10u V/M Frame and Lens Wood Durable Frame, Glass Lens Limited Warranty One Year Parts and Labor Viewing Distance 50 ft. -

Stauer Swiss Tactical Chronograph

WATCH DISPLAY TIMESETTING USING THE CHRONOGRAPH CHRONOGRAPH RESET A. TO SET THE TIME TO SET THE CHRONOGRAPH Chronograph Reset (includes after 1. Pull the crown (part C) out to position “2” This chronograph is able to measure and replacing the battery) B. G. and rotate it to the desired time. display time in 1 second increments up to a 1. Pull the crown (part C) out to position “2”. 2. Once the correct time is set, push the maximum of 59 minutes (part F) and 2. Press the Start/Stop Button (part B) to set 12 C. crown back into “0” (zero) position. The 59 seconds (part G). the Chronograph Second Hand (part F) to the 0 1 2 30 60 Seconds Dial (part A) will start to run. zero position. The chronograph hand can be 1. To start the Chronograph feature, press advanced rapidly by continuously pressing the the Start/Stop Button (part B). To measure 20 10 40 20 TO SET THE DATE Start/Stop Button (part B). split times press the Split/Reset Button (part 20 1. Pull the crown (part C) out to posi- 3. Once the Chronograph Second Hand (part D) to stop counting. tion “1” and rotate it clockwise (away from you) G) has been set to the zero position, push the to the desired date (part E). 2. Press the Split/Reset Button (part D) to F. 6 crown (part C) back into “0” (zero) position. D. 2. Once the correct date is set, push the crown reset the chronograph, and the Chronograph Minute Dial (part F) and the Chronograph To reset the Chronograph Minute (part H) E. -

C300 Abbreviated Instruction

English C300 Abbreviated instruction • To see details of specifications and operations, refer to the instruction manual: C300 instruction manual Component identification Setting the calendar The calendar of this watch does not have to be adjusted manually until Thursday, UTC hour hand UTC minute hand December 31, 2099 including leap years. (perpetual calendar) • Press and hold button B for 2 seconds or more to move the hour and minute Minute hand hands to 12 o'clock position temporarily to see the digital display without their MHP Button B 9:00 1:10 interruption. Press the button again to return them to normal movement. 8:00 Button A 1:20 22 24 2 M 20 4 1. Press and release the lower right button repeatedly to 7:00 1:30 Hour hand 18 6 16 UTC 8 move the mode hand to point to [CAL]. 14 1:40 12 10 24 6:00 20 4 The calendar is indicated on the digital display. PM AM 1:50 16 8 12 0 24-hour hand PM 2:0 A TME CAL 2. Press and release the upper right button or lower left 5:00 SET TM Digital display H.R. R AL-1 4:30 UP button C repeatedly to indicate an area name you want on CHR MODE DOWN AL-2 2:30 00 : AL-3 4 Button M 0 :3 3 the digital display. 0 0 Button C 3: Mode hand 3. Pull out the lower right button M. The calendar indication on the digital display starts blinking and the calendar becomes adjustable. -

Circular Motion Review KEY 1. Define Or Explain the Following: A

Circular Motion Review KEY 1. Define or explain the following: a. Frequency The number of times that an object moves around a circle in a given period of time. b. Period The amount of time needed for an object to move once around a circular path. c. Hertz The standard unit of frequency. 1 cycle/second (or 1 revolution per second) d. Centripetal Force The centrally directed force that causes an object’s tangential velocity to change direction as it moves around a circle. e. Centrifugal Force The imaginary outward force which you feel as you go around a turn in a car. This “force” is a consequence of you being accelerating and your brain interpreting your tendency to move in a straight line as a force. 2. Which of the following is NOT a property of Centripetal Force? a. It is unbalanced b. It always has a real source c. It is directed outward from the center of the circle d. Its magnitude is proportional to mass e. Its magnitude is proportional to the square of speed f. Its magnitude is inversely proportional to the radius of the circle g. It is the amount of force required to turn a particular object in a particular circle 3. If an object is swung by a string in a vertical circle, explain two reasons why the string is most likely to break at the bottom of the circle. 1. The string tension needs to overcome the weight of the object to provide the needed centripetal force. 2. The object is moving the fastest at the bottom unless some force keeps the object at a constant speed as it moves around the circle. -

Emerald Observatory Is an Ipad™ Application Which Displays a Variety of Astronomical Information

Emerald Observatory is an iPad™ application which displays a variety of astronomical information. It is similar in that way to our flagship products, Emerald Chronometer® and Emerald Chronometer HD, but designed from the start to take advantage of the iPad's larger display. Much of the supporting technology, including NTP (atomic time) and the highly accurate astronomical algorithms, was derived from Emerald Chronometer. Clock First of all, it's an ordinary clock. The main hands (gold colored) display the hours, minutes and seconds in the usual 12-hour format. To read it more precisely use the small numbers and tick marks on the inner edge of the rings. The thin central hand with the large white arrow head and the large white numbers and tick marks indicate the time in 24-hour format (with noon on top by default). Emerald Observatory's time may not exactly match the time in the iPad's status bar becausethe iPad's clock is often not very accurate whereas Emerald Observatory's time is synchronized with the international standard atomic clocks. This is usually accurate to about +/- 0.100 seconds. This is accomplished with the Network Time Protocol (NTP) so it must have a Net connection to get a sync. If the Net is not available, it will fall back to the internal clock's value. It is also possible to change the clock's time and to animate it at very high rates. See Set Mode, below. Moon In the upper left Emerald Observatory displays the Moon as it appears from the current location at the clock's time. -

Murten - Enjoy It the City by the Lake

ENGLISH VERSION Murten - Enjoy It The City by the Lake Attractions Citymap Events Old Town History Excursions www.murtentourismus.ch English Information TOURIST OFFICE Murten Tourismus Franz. Kirchgasse 6 PO Box 210 3280 Murten Tel. +41 (0)26 670 51 12 Fax +41 (0)26 670 49 83 [email protected] www.murtentourismus.ch Opening Hours: April until Sept. Mon-Fri: 9:00-12:00 and 13:00-18:00 Sat-Sun, Holidays: 10:00-12:00 and 13:00-17:00 Oct. until March: Mon-Fri: 09:00-12:00 and 14:00-17:00 Guided Tours The tourist information office offers a wide choice of guided tours. Contact us for more information. www.murtentourismus.ch/tours Signs and QR-Codes On the tour, you’ll see signs with QR codes which direct you to the Internet page, relating to the specific tourist attraction or monument you are viewing. The QR codes can be read with your smartphone. www.murtentourismus.ch/qr Welcome 1 Its relaxing atmosphere and mild climate lends a Mediterranean feeling to this historic medieval town, in the heart of Switzerland. Whether you stop off in one of the cafés or stroll along the lake, Murten shall certainly be a grand experience. Have a nice city tour! Morat in French or Murten in German Bilingualism is an important element of Morat’s/Murten’s identity. About 76% of the population is German speaking and 13% is French speaking. Throughout the ages, the region has been a bridge between languages and cultures. In the Heart of a Beautiful Region Murten is the Lake District’s main town, in the canton of Fribourg. -

By Robert H. Croswell a BRIEF HISTORY of AMERICAN CLOCK

By Robert H. Croswell A BRIEF HISTORY OF AMERICAN CLOCK MAKING The history of timekeeping devices is almost as old as time itself but it was not until about 1658 that the pendulum was introduced as part of the controlling mechanism. Although the name of the inventor is disputed, this improvement revolutionized the construction and accuracy of clocks. During the American colonial period, most clocks were imported from England or France and only the wealthy could afford one. By the mid 18th century numerous American clockmakers were making small numbers of tall case, or “grandfather” clocks. Brass and other materials commonly used in clock making were heavily taxed or just not available in the colonies, so these early clocks were generally made almost entirely of wood and powered by iron weights. Smaller shelf clocks with 1-day (30 hour) wooden movements were produced in fairly large quantities from around 1810 to 1845, after which most clock makers changed over to brass movements. By 1860 iron weights were being replaced by springs as the power source, and smaller clocks, many of them 8-day, were becoming increasingly popular. The last quarter of the 19th century saw many small clock making companies go out of business or be taken over by larger companies. By the year 1900 the vast majority of American clocks were being made by just over a half dozen huge companies. By the 1930s electric clocks had rapidly begun to replace mechanical clocks. CAN AN OLD CLOCK REALLY KEEP GOOD TIME? In order to answer that question one must first consider what is “good time”. -

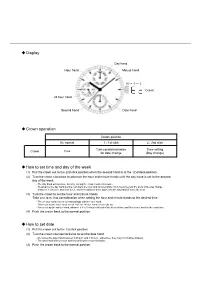

Display Crown Operation How to Set Date How to Set Time

Display Day hand Hour hand Minute hand N → 1 → 2 Crown 24 hour hand Second hand Date hand Crown operation Crown position N : normal 1 : 1st click 2 : 2nd click Turn counterclockwise Time setting Crown Free for date change (Day change) How to set time and day of the week (1) Pull the crown out to the 2nd click position when the second hand is at the 12 o'clock position. (2) Turn the crown clockwise to advance the hour and minute hands until the day hand is set to the desired day of the week. - The day hand will not move back by turning the crown counterclockwise. - To advance the day hand quickly, turn back the hour and minute hands 4 to 5 hours beyond the point of the day change (between 11:00 p.m. and 4:00 a.m.), and then advance them again until the day hand is set to the next. (3) Turn the crown to set the hour and minute hands. Take a.m./p.m. into consideration when setting the hour and minute hands to the desired time. - The 24 hour hand moves correspondingly with the hour hand. - When setting the hour hand, check that the 24 hour hand is correctly set. - When setting the minute hand, advance it 4 to 5 minutes ahead of the desired time and then turn it back to the exact time. (4) Push the crown back to the normal position. How to set date (1) Pull the crown out to the 1st click position. (2) Turn the crown counterclockwise to set the date hand. -

Clinician Position in Relation to the Treatment Area

© Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION MODULE 2 © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC NOT FOR SALEClinician OR DISTRIBUTION Position inNOT Relation FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION to the Treatment Area © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC NOT FOR SALEModule OR DISTRIBUTION Overview NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION The manner in which the seated clinician is positioned in relation to a treatment area is known as the clock position. This module introduces the traditional clock positions for periodontal instrumentation. © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTIONModule Outline NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION Section 1 Clock Positions for Instrumentation 41 Section 2 Positioning for the RIGHT-Handed Clinician 43 © Jones & BartlettSkill Building. Learning, Clock LLCPositions for the RIGHT-Handed© JonesClinician, & p. Bartlett 43 Learning, LLC NOT FOR SALEFlow OR Chart: DISTRIBUTION Sequence for Practicing Patient/ClinicianNOT Position FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION Use of Textbook during Skill Practice Quick Start Guide to the Anterior Sextants, p. 47 Skill Building. Clock Positions for the Anterior Surfaces Toward, p. 48 © Jones & Bartlett Learning,Skill LLC Building. Clock Positions for© the Jones Anterior & SurfacesBartlett Away, Learning, p. 49 LLC Quick Start Guide to the Posterior Sextants, p. 50 NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION Skill Building. Clock Positions for the Posterior Sextants, Aspects Facing Toward the Clinician, p. 51 Skill Building. Clock Positions for the Posterior Sextants, Aspects Facing Away From the Clinician, p. 52 © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC Reference Sheet:© Position Jones for & the Bartlett RIGHT-Handed Learning, Clinician LLC NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTIONSection 3 PositioningNOT for theFOR LEFT-Handed SALE OR DISTRIBUTION Clinician 54 Skill Building. -

The Digital Rectal Examination

Expert Review The Digital Rectal Examination Anna Shirley* and Simon Brewster# …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….. The Journal of Clinical Examination 2011 (11): 1-12 Abstract Digital rectal examination is an important skill for medical students and doctors. This article presents a comprehensive, concise and evidence-based approach to examination of the rectum which is consistent with The Principles of Clinical Examination [1]. We describe the signs of common and important diseases of the rectum and, based on a review of the literature, the precision and accuracy of these signs is discussed. Word Count: 2893 Key Words: digital rectal examination, rectum, anus Address for Correspondence: [email protected] Author affiliations: *Foundation Year 1 Doctor, Charring Cross Hospital, London. #Clinical Director of Urology, Oxford Radcliffe Hospitals NHS Trust. …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….. Introduction examination early in a medical career. The value of The importance of performing a digital rectal learning how to perform the DRE is increasingly examination (DRE) in the appropriate setting is being recognised across UK medical schools, and captured by the phrase, “If you don’t put your finger rectal examination mannequins are now used in in it, you put your foot in it.” – H. Bailey 1973 [2]. student training and beyond. They may also be Anorectal or urogenital symptoms account for 5- used to assess the skill in Objective Structured 10% of all general practice consultations [3] and the Clinical Examinations. DRE is part of the assessment of these. In addition, statistics from 2008 show that colorectal and The Context of the DRE prostate cancer were the third and forth most There are many circumstances in which a DRE is commonly diagnosed cancers in the UK considered to be appropriate. -

Operation Guide 4391

MA0702-EA Operation Guide 4391 I For a watch with an elapsed time bezel Rotate the elapsed time bezel to align the mark with the 10 Setting the Time and Day 0 minute hand. 5 Your watch lets you set two different times: one time with the hour and minute hands, After certain amount of time elapsed, read the graduation on 20 and another time with the 12-hour and 24-hour hands. 40 the elapsed time bezel which the minute hand points to. 30 The elapsed time is indicated. <Time with the hour and <Time with the 12-hour and minute hands (Dual Time)> 24-hour hands (Basic Time)> Elapsed time bezel Hour hand Minute hand 24-hour hand • Some water resistant models are equipped with a screw lock crown. • With such models, you must unscrew the crown in the direction noted in the illustration to loosen it before you can pull it out. Do not pull too forcibly on such crowns. • Also note that such watches are not water resistant while their crowns are loosened. Be sure to screw the crowns back in as far as they will go after making any setting. 30 30 12-hour hand The time indicated by the hour hand and minute hand (Dual Time) can be set to the time you want without stopping watch operation. You can set the 12-hour and 24-hour hands to your basic time (the current time in the time zone where you normally use the watch), and change the hour hand to any other time (Dual Time) you want (current time in a city you are visiting, etc.).