Atomic Clocks for Geodesy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NTIA Technical Report TR-89-241 Meteor–Burst System Communications Compatibility

NTIA REPORT 89·241 METEOR BURST SYSTEM COMMUNICATIONS COMPATIBILITY David Cohen William Grant Francis Steele U.S. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE Robert A. Mosbacher, Secretary Alfred C. Sikes, Assistant Secretary for Communications and Information MARCH 1989 ABSTRACT The technical and operating characteristics of meteor burst systems of importance for spectrum management appl i cati ons are i dent ifi ed. A techni ca1 assessment is included which identifies the most appropriate frequency subbands withi n the VHF spectrum to support meteor burst systems. The electromagnetic compatibility of meteor burst systems with other equipments in the VHF spectrum is determined using computerized analysis methods for both ionospheric and groundwave propagation modes. It is shown that meteor burst equipments can cause and are susceptible to groundwave interference from other VHF equipments. The report includes tables of geographical distance separations between meteor burst and other VHF equipments which satisfy interference threshold criteria. KEY WORDS Compat i bil ity Interference Meteor Bu rst Spectrum Management iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Subsection SECTION 1 INTRODUCTION BACKGROUND. ••••••••••••••••••••• .. • .. •••••••••• .. •••••••••••••••••••••••• • • • • 1 OBJECTIVES •••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 2 APPROACH ••••••••• e'. ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 2 SECTION 2 CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS CONCLUSIONS.... ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• ••• •••• •••••••• • 4 FREQUENCY USE •••••••••••••• -

Type II Familial Synpolydactyly: Report on Two Families with an Emphasis on Variations of Expression

European Journal of Human Genetics (2011) 19, 112–114 & 2011 Macmillan Publishers Limited All rights reserved 1018-4813/11 www.nature.com/ejhg SHORT REPORT Type II familial synpolydactyly: report on two families with an emphasis on variations of expression Mohammad M Al-Qattan*,1 Type II familial synpolydactyly is rare and is known to have variable expression. However, no previous papers have attempted to review these variations. The aim of this paper was to review these variations and show several of these variable expressions in two families. The classic features of type II familial synpolydactyly are bilateral synpolydactyly of the third web spaces of the hands and bilateral synpolydactyly of the fourth web spaces of the feet. Several members of the two families reported in this paper showed the following variations: the third web spaces of the hands showing syndactyly without the polydactyly, normal feet, concurrent polydactyly of the little finger, concurrent clinodactyly of the little finger and the ‘homozygous’ phenotype. It was concluded that variable expressions of type II familial synpolydactyly are common and awareness of such variations is important to clinicians. European Journal of Human Genetics (2011) 19, 112–114; doi:10.1038/ejhg.2010.127; published online 18 August 2010 Keywords: type II familial syndactyly; inherited synpolydactyly; variations of expression INTRODUCTION CASE REPORTS Type II familial synpolydactyly is rare and it has been reported in o30 The first family families.1–12 It is characterized by bilateral synpolydactyly of the third The family had a history of synpolydactyly type II for several web spaces of the hands and bilateral synpolydactyly of the fourth web generations on the mother’s side (Table 1). -

Measuring the Speed of Light and the Moon Distance with an Occultation of Mars by the Moon: a Citizen Astronomy Campaign

Measuring the speed of light and the moon distance with an occultation of Mars by the Moon: a Citizen Astronomy Campaign Jorge I. Zuluaga1,2,3,a, Juan C. Figueroa2,3, Jonathan Moncada4, Alberto Quijano-Vodniza5, Mario Rojas5, Leonardo D. Ariza6, Santiago Vanegas7, Lorena Aristizábal2, Jorge L. Salas8, Luis F. Ocampo3,9, Jonathan Ospina10, Juliana Gómez3, Helena Cortés3,11 2 FACom - Instituto de Física - FCEN, Universidad de Antioquia, Medellín-Antioquia, Colombia 3 Sociedad Antioqueña de Astronomía, Medellín-Antioquia, Colombia 4 Agrupación Castor y Pollux, Arica, Chile 5 Observatorio Astronómico Universidad de Nariño, San Juan de Pasto-Nariño, Colombia 6 Asociación de Niños Indagadores del Cosmos, ANIC, Bogotá, Colombia 7 Organización www.alfazoom.info, Bogotá, Colombia 8 Asociación Carabobeña de Astronomía, San Diego-Carabobo, Venezuela 9 Observatorio Astronómico, Instituto Tecnológico Metropolitano, Medellín, Colombia 10 Sociedad Julio Garavito Armero para el Estudio de la Astronomía, Medellín, Colombia 11 Planetario de Medellín, Parque Explora, Medellín, Colombia ABSTRACT In July 5th 2014 an occultation of Mars by the Moon was visible in South America. Citizen scientists and professional astronomers in Colombia, Venezuela and Chile performed a set of simple observations of the phenomenon aimed to measure the speed of light and lunar distance. This initiative is part of the so called “Aristarchus Campaign”, a citizen astronomy project aimed to reproduce observations and measurements made by astronomers of the past. Participants in the campaign used simple astronomical instruments (binoculars or small telescopes) and other electronic gadgets (cell-phones and digital cameras) to measure occultation times and to take high resolution videos and pictures. In this paper we describe the results of the Aristarchus Campaign. -

Expression of GNSS Positioning Error in Terms of Distance

Filić M, Filjar R, Ševrović M. Expression of GNSS Positioning Error in Terms of Distance MIA FILIĆ, mag. inf. et math.1 Transport Engineering E-mail: [email protected] Preliminary Communication RENATO FILJAR, Ph.D.2 Submitted: 4 Nov. 2016 E-mail: [email protected] Accepted: 11 Apr. 2018 MARKO ŠEVROVIĆ, Ph.D.3 (Corresponding author) E-mail: [email protected] 1 University of Zagreb Faculty of Electrical Engineering and Computing Unska 3, 10000 Zagreb 2 University of Rijeka, Faculty of Engineering Vukovarska 58, 51000 Rijeka, Croatia 3 University of Zagreb Faculty of Transport and Traffic Sciences Vukelićeva 4, 10000 Zagreb, Croatia EXPRESSION OF GNSS POSITIONING ERROR IN TERMS OF DISTANCE ABSTRACT methodology development, and simplifications used, This manuscript analyzes two methods for Global Nav- thus undermining the value of research and providing igation Satellite System positioning error determination for meaningless and non-comparable results [2]. positioning performance assessment by calculation of the In our research, we address the problem by assess- distance between the observed and the true positions: one ing the possible approaches to express GNSS position- using the Cartesian 3D rectangular coordinate system, and ing accuracy for navigation (i.e., used for applications the other using the spherical coordinate system, the Carte- to non-stationary objects, such as those belonging to sian reference frame distance method, and haversine for- location-based services (LBS) and intelligent trans- mula for distance calculation. The study shows unresolved issues in the utilization of position estimates in geographical port systems (ITS) [3]), and propose a solution for a reference frame for GNSS positioning performance assess- common methodology that will allow for comparison ment. -

12.2% 108,000 1.7 M Top 1% 151 3,500

We are IntechOpen, the world’s leading publisher of Open Access books Built by scientists, for scientists 3,500 108,000 1.7 M Open access books available International authors and editors Downloads Our authors are among the 151 TOP 1% 12.2% Countries delivered to most cited scientists Contributors from top 500 universities Selection of our books indexed in the Book Citation Index in Web of Science™ Core Collection (BKCI) Interested in publishing with us? Contact [email protected] Numbers displayed above are based on latest data collected. For more information visit www.intechopen.com Chapter 1 Geomatics Applications to Contemporary Social and Environmental Problems in Mexico Jose Luis Silván-Cárdenas, Rodrigo Tapia-McClung, Camilo Caudillo-Cos, Pablo López-Ramírez, Oscar Sanchez-Sórdia and Daniela Moctezuma-Ochoa Additional information is available at the end of the chapter http://dx.doi.org/10.5772/64355 Abstract Trends in geospatial technologies have led to the development of new powerful analysis and representation techniques that involve processing of massive datasets, some unstructured, some acquired from ubiquitous sources, and some others from remotely located sensors of different kinds, all of which complement the structured information produced on a regular basis by governmental and international agencies. In this chapter, we provide both an extensive revision of such techniques and an insight of the applica‐ tions of some of these techniques in various study cases in Mexico for various scales of analysis from regional migration flows of highly qualified people at the country level and the spatio-temporal analysis of unstructured information in geotagged tweets for sentiment assessment, to more local applications of participatory cartography for policy definitions jointly between local authorities and citizens, and an automated method for three dimensional D modelling and visualisation of forest inventorying with laser scanner technology. -

Stauer Swiss Tactical Chronograph

WATCH DISPLAY TIMESETTING USING THE CHRONOGRAPH CHRONOGRAPH RESET A. TO SET THE TIME TO SET THE CHRONOGRAPH Chronograph Reset (includes after 1. Pull the crown (part C) out to position “2” This chronograph is able to measure and replacing the battery) B. G. and rotate it to the desired time. display time in 1 second increments up to a 1. Pull the crown (part C) out to position “2”. 2. Once the correct time is set, push the maximum of 59 minutes (part F) and 2. Press the Start/Stop Button (part B) to set 12 C. crown back into “0” (zero) position. The 59 seconds (part G). the Chronograph Second Hand (part F) to the 0 1 2 30 60 Seconds Dial (part A) will start to run. zero position. The chronograph hand can be 1. To start the Chronograph feature, press advanced rapidly by continuously pressing the the Start/Stop Button (part B). To measure 20 10 40 20 TO SET THE DATE Start/Stop Button (part B). split times press the Split/Reset Button (part 20 1. Pull the crown (part C) out to posi- 3. Once the Chronograph Second Hand (part D) to stop counting. tion “1” and rotate it clockwise (away from you) G) has been set to the zero position, push the to the desired date (part E). 2. Press the Split/Reset Button (part D) to F. 6 crown (part C) back into “0” (zero) position. D. 2. Once the correct date is set, push the crown reset the chronograph, and the Chronograph Minute Dial (part F) and the Chronograph To reset the Chronograph Minute (part H) E. -

C300 Abbreviated Instruction

English C300 Abbreviated instruction • To see details of specifications and operations, refer to the instruction manual: C300 instruction manual Component identification Setting the calendar The calendar of this watch does not have to be adjusted manually until Thursday, UTC hour hand UTC minute hand December 31, 2099 including leap years. (perpetual calendar) • Press and hold button B for 2 seconds or more to move the hour and minute Minute hand hands to 12 o'clock position temporarily to see the digital display without their MHP Button B 9:00 1:10 interruption. Press the button again to return them to normal movement. 8:00 Button A 1:20 22 24 2 M 20 4 1. Press and release the lower right button repeatedly to 7:00 1:30 Hour hand 18 6 16 UTC 8 move the mode hand to point to [CAL]. 14 1:40 12 10 24 6:00 20 4 The calendar is indicated on the digital display. PM AM 1:50 16 8 12 0 24-hour hand PM 2:0 A TME CAL 2. Press and release the upper right button or lower left 5:00 SET TM Digital display H.R. R AL-1 4:30 UP button C repeatedly to indicate an area name you want on CHR MODE DOWN AL-2 2:30 00 : AL-3 4 Button M 0 :3 3 the digital display. 0 0 Button C 3: Mode hand 3. Pull out the lower right button M. The calendar indication on the digital display starts blinking and the calendar becomes adjustable. -

Circular Motion Review KEY 1. Define Or Explain the Following: A

Circular Motion Review KEY 1. Define or explain the following: a. Frequency The number of times that an object moves around a circle in a given period of time. b. Period The amount of time needed for an object to move once around a circular path. c. Hertz The standard unit of frequency. 1 cycle/second (or 1 revolution per second) d. Centripetal Force The centrally directed force that causes an object’s tangential velocity to change direction as it moves around a circle. e. Centrifugal Force The imaginary outward force which you feel as you go around a turn in a car. This “force” is a consequence of you being accelerating and your brain interpreting your tendency to move in a straight line as a force. 2. Which of the following is NOT a property of Centripetal Force? a. It is unbalanced b. It always has a real source c. It is directed outward from the center of the circle d. Its magnitude is proportional to mass e. Its magnitude is proportional to the square of speed f. Its magnitude is inversely proportional to the radius of the circle g. It is the amount of force required to turn a particular object in a particular circle 3. If an object is swung by a string in a vertical circle, explain two reasons why the string is most likely to break at the bottom of the circle. 1. The string tension needs to overcome the weight of the object to provide the needed centripetal force. 2. The object is moving the fastest at the bottom unless some force keeps the object at a constant speed as it moves around the circle. -

Emerald Observatory Is an Ipad™ Application Which Displays a Variety of Astronomical Information

Emerald Observatory is an iPad™ application which displays a variety of astronomical information. It is similar in that way to our flagship products, Emerald Chronometer® and Emerald Chronometer HD, but designed from the start to take advantage of the iPad's larger display. Much of the supporting technology, including NTP (atomic time) and the highly accurate astronomical algorithms, was derived from Emerald Chronometer. Clock First of all, it's an ordinary clock. The main hands (gold colored) display the hours, minutes and seconds in the usual 12-hour format. To read it more precisely use the small numbers and tick marks on the inner edge of the rings. The thin central hand with the large white arrow head and the large white numbers and tick marks indicate the time in 24-hour format (with noon on top by default). Emerald Observatory's time may not exactly match the time in the iPad's status bar becausethe iPad's clock is often not very accurate whereas Emerald Observatory's time is synchronized with the international standard atomic clocks. This is usually accurate to about +/- 0.100 seconds. This is accomplished with the Network Time Protocol (NTP) so it must have a Net connection to get a sync. If the Net is not available, it will fall back to the internal clock's value. It is also possible to change the clock's time and to animate it at very high rates. See Set Mode, below. Moon In the upper left Emerald Observatory displays the Moon as it appears from the current location at the clock's time. -

Capturing the Spatial Relatedness of Long-Distance Caregiving: a Mixed-Methods Approach

International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health Article Capturing the Spatial Relatedness of Long-Distance Caregiving: A Mixed-Methods Approach Tatjana Fischer 1,* and Markus Jobst 2 1 Institute of Spatial Planning, Environmental Planning and Land Rearrangement, University of Natural Resources and Life Sciences Vienna, Peter-Jordan-Straße 82, 1190 Vienna, Austria 2 Department for Geodesy and Geoinformation, Research Group Cartography, Vienna University of Technology, Erzherzog-Johann-Platz 1/120-6, 1040 Vienna, Austria; [email protected] * Correspondence: tatjana.fi[email protected]; Tel.: +43-1-47654-85517 Received: 29 July 2020; Accepted: 29 August 2020; Published: 2 September 2020 Abstract: Long-distance caregiving (LDC) is an issue of growing importance in the context of assessing the future of elder care and the maintenance of health and well-being of both the cared-for persons and the long-distance caregivers. Uncertainty in the international discussion relates to the relevance of spatially related aspects referring to the burdens of the long-distance caregiver and their (longer-term) willingness and ability to provide care for their elderly relatives. This paper is the result of a first attempt to operationalize and comprehensively analyze the spatial relatedness of long-distance caregiving against the background of the international literature by combining a longitudinal single case study of long-distance caregiving person and semantic hierarchies. In the cooperation of spatial sciences and geoinformatics an analysis grid based on a graph-theoretical model was developed. The elaborated conceptual framework should stimulate a more detailed and precise interdisciplinary discussion on the spatial relatedness of long-distance caregiving and, thus, is open for further refinement in order to become a decision-support tool for policy-makers responsible for social and elder care and health promotion. -

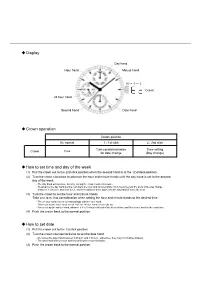

Display Crown Operation How to Set Date How to Set Time

Display Day hand Hour hand Minute hand N → 1 → 2 Crown 24 hour hand Second hand Date hand Crown operation Crown position N : normal 1 : 1st click 2 : 2nd click Turn counterclockwise Time setting Crown Free for date change (Day change) How to set time and day of the week (1) Pull the crown out to the 2nd click position when the second hand is at the 12 o'clock position. (2) Turn the crown clockwise to advance the hour and minute hands until the day hand is set to the desired day of the week. - The day hand will not move back by turning the crown counterclockwise. - To advance the day hand quickly, turn back the hour and minute hands 4 to 5 hours beyond the point of the day change (between 11:00 p.m. and 4:00 a.m.), and then advance them again until the day hand is set to the next. (3) Turn the crown to set the hour and minute hands. Take a.m./p.m. into consideration when setting the hour and minute hands to the desired time. - The 24 hour hand moves correspondingly with the hour hand. - When setting the hour hand, check that the 24 hour hand is correctly set. - When setting the minute hand, advance it 4 to 5 minutes ahead of the desired time and then turn it back to the exact time. (4) Push the crown back to the normal position. How to set date (1) Pull the crown out to the 1st click position. (2) Turn the crown counterclockwise to set the date hand. -

Clinician Position in Relation to the Treatment Area

© Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION MODULE 2 © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC NOT FOR SALEClinician OR DISTRIBUTION Position inNOT Relation FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION to the Treatment Area © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC NOT FOR SALEModule OR DISTRIBUTION Overview NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION The manner in which the seated clinician is positioned in relation to a treatment area is known as the clock position. This module introduces the traditional clock positions for periodontal instrumentation. © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTIONModule Outline NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION Section 1 Clock Positions for Instrumentation 41 Section 2 Positioning for the RIGHT-Handed Clinician 43 © Jones & BartlettSkill Building. Learning, Clock LLCPositions for the RIGHT-Handed© JonesClinician, & p. Bartlett 43 Learning, LLC NOT FOR SALEFlow OR Chart: DISTRIBUTION Sequence for Practicing Patient/ClinicianNOT Position FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION Use of Textbook during Skill Practice Quick Start Guide to the Anterior Sextants, p. 47 Skill Building. Clock Positions for the Anterior Surfaces Toward, p. 48 © Jones & Bartlett Learning,Skill LLC Building. Clock Positions for© the Jones Anterior & SurfacesBartlett Away, Learning, p. 49 LLC Quick Start Guide to the Posterior Sextants, p. 50 NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION Skill Building. Clock Positions for the Posterior Sextants, Aspects Facing Toward the Clinician, p. 51 Skill Building. Clock Positions for the Posterior Sextants, Aspects Facing Away From the Clinician, p. 52 © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC Reference Sheet:© Position Jones for & the Bartlett RIGHT-Handed Learning, Clinician LLC NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTIONSection 3 PositioningNOT for theFOR LEFT-Handed SALE OR DISTRIBUTION Clinician 54 Skill Building.