The Equatorial Sundial Telling Time with the Sun

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Daylight Saving Time

Daylight Saving Time Beth Cook Information Research Specialist March 9, 2016 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov R44411 Daylight Saving Time Summary Daylight Saving Time (DST) is a period of the year between spring and fall when clocks in the United States are set one hour ahead of standard time. DST is currently observed in the United States from 2:00 a.m. on the second Sunday in March until 2:00 a.m. on the first Sunday in November. The following states and territories do not observe DST: Arizona (except the Navajo Nation, which does observe DST), Hawaii, American Samoa, Guam, the Northern Mariana Islands, Puerto Rico, and the Virgin Islands. Congressional Research Service Daylight Saving Time Contents When and Why Was Daylight Saving Time Enacted? .................................................................... 1 Has the Law Been Amended Since Inception? ................................................................................ 2 Which States and Territories Do Bot Observe DST? ...................................................................... 2 What Other Countries Observe DST? ............................................................................................. 2 Which Federal Agency Regulates DST in the United States? ......................................................... 3 How Does an Area Move on or off DST? ....................................................................................... 3 How Can States and Territories Change an Area’s Time Zone? ..................................................... -

The Sundial, Beyond the Form and Time

ISAMA BRIDGES The International Society of the Mathematical Connections Arts, Mathematics, and Architecture in Art, Music, and Science The Sundial, Beyond the Form and Time ... Andrzej Zarzycki 227 Brighton Street Belmont, MA 02478 E-mail: [email protected] Abstract Architecture (iir" k 1-t].lk" ch ... r) n. 1. The art and science of designing and erecting buildings. Can a building inspire scientific thinking? Can an architectural structure reflect the complexity of the universe? Is there a relationship between the artistic and scientific? This paper discusses an approach to design, which uses an architectural structure as a research apparatus to pursue scientifically driven beauty. Architecture could be defined as the man-made universe - the universe whose primary function was to shelter us from elements, animals and other people. Broadly speaking, to protect us from the "outer Uni verse". It is not surprising that the evolution of architecture follows the same trajectories as the evolution of our thinking and perception ofthe surrounding world. However, somewhere along the lines of history, archi tecture acquired another purpose and began to playa new role in our self-awareness. In ancient, medieval and even modem times, we have viewed architecture as a medium to express, symbolize, and address the meaning of our existence. Ancient temples reveal an intimate knowledge of geometry and human perception by purposefully distorting their forms to balance visual illusions. Medieval cathedrals manifested greatness of God through art and structural achievements, while contemporary monu ments address the social and philosophical aspirations of a present-day society. As a result of this centuries long evolution~ we now associate architecture with its less utilitarian and more symbolic values. -

Hourglass User and Installation Guide About This Manual

HourGlass Usage and Installation Guide Version7Release1 GC27-4557-00 Note Before using this information and the product it supports, be sure to read the general information under “Notices” on page 103. First Edition (December 2013) This edition applies to Version 7 Release 1 Mod 0 of IBM® HourGlass (program number 5655-U59) and to all subsequent releases and modifications until otherwise indicated in new editions. Order publications through your IBM representative or the IBM branch office serving your locality. Publications are not stocked at the address given below. IBM welcomes your comments. For information on how to send comments, see “How to send your comments to IBM” on page vii. © Copyright IBM Corporation 1992, 2013. US Government Users Restricted Rights – Use, duplication or disclosure restricted by GSA ADP Schedule Contract with IBM Corp. Contents About this manual ..........v Using the CICS Audit Trail Facility ......34 Organization ..............v Using HourGlass with IMS message regions . 34 Summary of amendments for Version 7.1 .....v HourGlass IOPCB Support ........34 Running the HourGlass IMS IVP ......35 How to send your comments to IBM . vii Using HourGlass with DB2 applications .....36 Using HourGlass with the STCK instruction . 36 If you have a technical problem .......vii Method 1 (re-assemble) .........37 Method 2 (patch load module) .......37 Chapter 1. Introduction ........1 Using the HourGlass Audit Trail Facility ....37 Setting the date and time values ........3 Understanding HourGlass precedence rules . 38 Introducing -

Atomic Desktop Alarm Clock

MODEL: T-045 (FRONT) INSTRUCTION MANUAL SCALE: 480W x 174H mm DATE: June 3, 2009 COLOR: WHITE BACKGROUND PRINTING BLACK 2. When the correct hour appears press the MODE button once to start the Minute digits Activating The Alarm Limited 90-Day Warranty Information Model T045 flashing, then press either the UP () or DOWN () buttons to set the display to the To turn the alarm ‘On’ slide the ALARM switch on the back panel to the ‘On’ position. The correct minute. Alarm On indicator appears in the display. Timex Audio Products, a division of SDI Technologies Inc. (hereafter referred to as SDI Technologies), warrants this product to be free from defects in workmanship and materials, under normal use Atomic Desktop 3. When the correct minutes appear press the MODE button once to start the Seconds At the selected wake-up time the alarm turns on automatically. The alarm begins with a single and conditions, for a period of 90 days from the date of original purchase. digits flashing. If you want to set the seconds counter to “00” press either the UP () or ‘beep’ and then the frequency of the ‘beeps’ increases. The alarm continues for two minutes, Alarm Clock DOWN () button once. If you do not wish to ‘zero’ the seconds, proceed to step 4. then shuts off automatically and resets itself for the same time on the following day. Should service be required by reason of any defect or malfunction during the warranty period, SDI Technologies will repair or, at its discretion, replace this product without charge (except for a 4. -

Daylight Saving Time (DST)

Daylight Saving Time (DST) Updated September 30, 2020 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R45208 Daylight Saving Time (DST) Summary Daylight Saving Time (DST) is a period of the year between spring and fall when clocks in most parts of the United States are set one hour ahead of standard time. DST begins on the second Sunday in March and ends on the first Sunday in November. The beginning and ending dates are set in statute. Congressional interest in the potential benefits and costs of DST has resulted in changes to DST observance since it was first adopted in the United States in 1918. The United States established standard time zones and DST through the Calder Act, also known as the Standard Time Act of 1918. The issue of consistency in time observance was further clarified by the Uniform Time Act of 1966. These laws as amended allow a state to exempt itself—or parts of the state that lie within a different time zone—from DST observance. These laws as amended also authorize the Department of Transportation (DOT) to regulate standard time zone boundaries and DST. The time period for DST was changed most recently in the Energy Policy Act of 2005 (EPACT 2005; P.L. 109-58). Congress has required several agencies to study the effects of changes in DST observance. In 1974, DOT reported that the potential benefits to energy conservation, traffic safety, and reductions in violent crime were minimal. In 2008, the Department of Energy assessed the effects to national energy consumption of extending DST as changed in EPACT 2005 and found a reduction in total primary energy consumption of 0.02%. -

TS4002 Wireless Synchronized Analog Clock Is Designed with an Easy-To-Read Dial Face, Durable Cherry Finished Wood Frame and Tamper-Proof Glass Lens

TS4002 - Wireless Synchronized Analog Clock The TS4002 Wireless Synchronized Analog Clock is designed with an easy-to-read dial face, durable cherry finished wood frame and tamper-proof glass lens. The TS4002 receives a wireless time signal transmitted daily by a main wireless paging controller, such as the VS4800. The TS4002 uses the time signal to automatically adjust itself, if necessary, to ensure accurate and synchronized time throughout the entire facility. The TS4002 does not require any wiring and is ideal for renovation projects and new installations. The TS4002 has a traditional look that matches a wide variety of applications and provides years of maintenance-free service. Key Features: • Viewing Distance of 50' • Automatic Daylight Saving Time Adjustment • Glass Lens • Quick Correction for Time Change (1-3 Minutes) • Flush Mount (Does Not Require Back Box) • Battery Operated (Optional AC Power Adaptor) • Customized Logo Option Options, Accessories and Complementary Products: Part Number Description TS-OPT-003 24-Hour Clock Face TS-OPT-004 Customized Analog Clock Face TS-OPT-005 Sealed Analog Clock TS-OPT-007 110 V AC Adaptor (Replaces Original Clock Batteries, Requires 1.5" Minimum Recessed Power Outlet) TS-OPT-011 Red Second Hand Specifications: Dimensions 19.5" x 8.5" x 2.05" (W x H x D) Dial Face 8", White Weight 5.25 lbs. Frequency VHF (148 - 174 MHz), UHF (400 - 470 MHz) Power Two AA Sized Batteries Paging Format POCSAG, Narrow Band Operating Temperature 32º - 120ºF Synchronization 1 Time/Day (Optional 6 Times/Day, User Selectable) Humidity 0% - 95%, Non-Condensing Receiver Sensitivity 10u V/M Frame and Lens Wood Durable Frame, Glass Lens Limited Warranty One Year Parts and Labor Viewing Distance 50 ft. -

How to Add Another Time Zone to a Lotus Notes Calendar

How to Add Another Time Zone to a Lotus Notes Calendar Adding another Lotus Notes 8 allows users to set up more than one time zone in their calendar views. time zone to Please follow the steps in the table below to add another time zone to your calendar. Lotus Notes Calendar Note: This process has only been tested for Lotus Notes 8. Step Action 1 Open Lotus Notes 2 Navigate to the Calendar 3 In the lower right corner, click on the In Office drop-down menu and select Edit Locations… 4 In the navigator on the left, select Calendar and To Do, then Regional Settings 5 In the Time Zone section, checkmark the Display an additional time zone option 6 Enter the Time zone label that you wish to use Note: This is a free-form text field and is for the user only. It does not impact any system functionality. 7 Use the Time Zone drop-down to select the time zone that you wish to add Continued on next page How To Add Another Time Zone To A Lotus Notes Calendar.Doc Page 1 of 2 How to Add Another Time Zone to a Lotus Notes Calendar, Continued Adding another time zone to Step Action Lotus Notes 8 As desired, checkmark the Display an additional time zone in the main calendar Calendar and/or the Display an additional time zone in the Day-At-A-Glance calendar options (continued) 9 Once all options have been filled out, click the Save button 10 Verify that the calendar displays the time zones correctly How To Add Another Time Zone To A Lotus Notes Calendar.Doc Page 2 of 2 . -

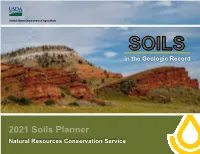

Soils in the Geologic Record

in the Geologic Record 2021 Soils Planner Natural Resources Conservation Service Words From the Deputy Chief Soils are essential for life on Earth. They are the source of nutrients for plants, the medium that stores and releases water to plants, and the material in which plants anchor to the Earth’s surface. Soils filter pollutants and thereby purify water, store atmospheric carbon and thereby reduce greenhouse gasses, and support structures and thereby provide the foundation on which civilization erects buildings and constructs roads. Given the vast On February 2, 2020, the USDA, Natural importance of soil, it’s no wonder that the U.S. Government has Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) an agency, NRCS, devoted to preserving this essential resource. welcomed Dr. Luis “Louie” Tupas as the NRCS Deputy Chief for Soil Science and Resource Less widely recognized than the value of soil in maintaining Assessment. Dr. Tupas brings knowledge and experience of global change and climate impacts life is the importance of the knowledge gained from soils in the on agriculture, forestry, and other landscapes to the geologic record. Fossil soils, or “paleosols,” help us understand NRCS. He has been with USDA since 2004. the history of the Earth. This planner focuses on these soils in the geologic record. It provides examples of how paleosols can retain Dr. Tupas, a career member of the Senior Executive Service since 2014, served as the Deputy Director information about climates and ecosystems of the prehistoric for Bioenergy, Climate, and Environment, the Acting past. By understanding this deep history, we can obtain a better Deputy Director for Food Science and Nutrition, and understanding of modern climate, current biodiversity, and the Director for International Programs at USDA, ongoing soil formation and destruction. -

History of Sundials

History of Sundials The earliest record of the sundial dates back as early as 3500 BCE. At this time the ancient Egyptians were building tall, slender monuments from stone, called obelisks, which cast shadows that functioned like a sundial. Obelisks enabled people to divide the day into morning and afternoon, and they also showed the longest and shortest days of the year when the shadow they cast was longest or shortest at noon. Later on, additional markers were added around the base of the obelisk to indicate further subdivisions of time. Possibly the first portable timepiece came into use around 1500 BCE. Still a sundial, this was another Egyptian invention and it divided the day into ten parts plus two “twilight hours” in the morning and evening; was this the origin of the “twelve hour day” that we know today? Around 600 BCE the Egyptians came up with another invention, the merkhet (the oldest known astronomical tool), which allowed them to tell the time at night when there was no sun to cast a shadow. The merkhet worked in a similar way to a sundial: you would line up a pair of them in a north-south direction using the Pole Star, and then as certain stars crossed that line you would be able to tell what time it was. In the pursuit of year-round accuracy sundials gradually developed from their original shape, of a flat or vertical plate or surface, to much more elaborate forms. One version was a bowl-shape, cut into a block of stone, with a central vertical pointer (gnomon) whose shadow fell on lines marking sets of hour lines for different seasons. -

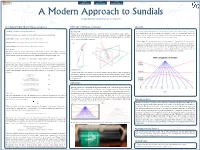

A Modern Approach to Sundial Design

SARENA ANISSA DR. JASON ROBERTSON ZACHARIAS AUFDENBERG A Modern Approach to Sundials DEPARTMENT OF PHYSICAL SCIENCES INTRODUCTION TO VERTICAL SUNDIALS TYPES OF VERTICAL SUNDIALS RESULTS Gnomon: casts the shadow onto the sundial face Reclining Dials A small scale sundial model printed out and proved to be correct as far as the hour lines go, and only a Reclining dials are generally oriented along a north-south line, for example they face due south for a minor adjustment to the gnomon length was necessary in order for the declination lines to be Nodus: the location along the gnomon that marks the time and date on the dial plate sundial in the Northern hemisphere. In such a case the dial surface would have no declination. Reclining validated. This was possible since initial calibration fell on a date near the vernal equinox, therefore the sundials are at an angle from the vertical, and have gnomons directly parallel with Earth’s rotational axis tip of the shadow should have fell just below the equinox declination line. angular distance of the gnomon from the dial face Style Height: which is visually represented in Figure 1a). Shown in Figure 3 is the final sundial corrected for the longitude of Daytona Beach, FL. If the dial were Substyle Line: line lying in the dial plane perpendicularly behind the style 1b) 1a) not corrected for longitude, the noon line would fall directly vertical from the gnomon base. For verti- cal dials, the shortest shadow will be will the sun has its lowest altitude in the sky. For the Northern Substyle Angle: angle that the substyle makes with the noon-line hemisphere, this is the Winter Solstice declination line. -

Standard Time Zones

APPENDIX B Standard Time Zones Table B-1 lists all the standard time zones that you can configure on an MDE and the offset from Coordinated Universal Time (UTC) for each standard time zone. The offset (ahead or behind) UTC in hours, as displayed in Table B-1, is in effect during winter time. During summer time or daylight saving time, the offset may be different from the values in the table and are calculated and displayed accordingly by the system clock. Note The time zone entry is case sensitive and must be specified in the exact notation listed in the following time zone table. When you use a time zone entry from the following time zone table, the system is automatically adjusted for daylight saving time. Table B-1 List of Standard Time Zones and Offsets from UTC Time Zone Offset from UTC Africa/Abidjan 0 Africa/Accra 0 Africa/Addis_Ababa +3 Africa/Algiers +1 Africa/Asmera +3 Africa/Bamako 0 Africa/Bangui +1 Africa/Banjul 0 Africa/Bissau 0 Africa/Blantyre +2 Africa/Brazzaville +1 Africa/Bujumbura +2 Africa/Cairo +2 Africa/Casablanca 0 Africa/Ceuta +1 Africa/Conakry 0 Africa/Dakar 0 Africa/Dar_es_Salaam +3 B-1 Appendix B Standard Time Zones Table B-1 List of Standard Time Zones and Offsets from UTC (continued) Time Zone Offset from UTC Africa/Djibouti +3 Africa/Douala +3 Africa/El_Aaiun +1 Africa/Freetown 0 Africa/Gaborone +2 Africa/Harare +2 Africa/Johannesburg +2 Africa/Kampala +3 Africa/Khartoum +3 Africa/Kigali +2 Africa/Kinshasa +1 Africa/Lagos +1 Africa/Libreville +1 Africa/Lome 0 Africa/Luanda +1 Africa/Lubumbashi +2 Africa/Lusaka -

Physics: Sundial Science

Physics: Sundial Science MAIN IDEA Discover how the sun and its shadow is used to tell time by creating a sundial – an instrument that tracks the position of the sun to indicate time of day. SCIENCE BACKGROUND For centuries humans, have utilized the power of the sun as a light source, to grow food, and to tell time. Ancient civilizations used the sun to understand basic astronomy. By tracking the height of the sun in the sky, these civilizations developed calendars for the year and were able to identify harvesting and planting seasons (fall and spring equinoxes) all by tracking the movement of the sun. This also helped certain civilizations find the Equator, an imaginary circle around the Earth that divides it into two halves, the northern and southern hemisphere. By tracking the sun’s apparent position through the creation of sundials, these ancient civilizations were able to divide the day into morning and afternoon. A sundial is a device used to track time by marking a shadow on its surface as the sun moves. Light travels as a wave, similar to waves in the ocean. Shadows occur when this light wave is blocked by an object, creating a dark silhouette of that object on nearby surfaces as light continues to travel all around the object. Based on where the light source is, and the object that is blocking it, the shadow will look different. This is why for a sundial, the shadow will change throughout the day and even more noticeably throughout the year for the same time of day.