The History of Corporate Ownership in Japan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Foreign Direct Investment and Keiretsu: Rethinking U.S. and Japanese Policy

This PDF is a selection from an out-of-print volume from the National Bureau of Economic Research Volume Title: The Effects of U.S. Trade Protection and Promotion Policies Volume Author/Editor: Robert C. Feenstra, editor Volume Publisher: University of Chicago Press Volume ISBN: 0-226-23951-9 Volume URL: http://www.nber.org/books/feen97-1 Conference Date: October 6-7, 1995 Publication Date: January 1997 Chapter Title: Foreign Direct Investment and Keiretsu: Rethinking U.S. and Japanese Policy Chapter Author: David E. Weinstein Chapter URL: http://www.nber.org/chapters/c0310 Chapter pages in book: (p. 81 - 116) 4 Foreign Direct Investment and Keiretsu: Rethinking U.S. and Japanese Policy David E. Weinstein For twenty-five years, the U.S. and Japanese governments have seen the rise of corporate groups in Japan, keiretsu, as due in part to foreign pressure to liberal- ize the Japanese market. In fact, virtually all works that discuss barriers in a historical context argue that Japanese corporations acted to insulate themselves from foreign takeovers by privately placing shares with each other (See, e.g., Encarnation 1992,76; Mason 1992; and Lawrence 1993). The story has proved to be a major boon for the opponents of a neoclassical approach to trade and investment policy. Proponents of the notion of “Japanese-style capitalism” in the Japanese government can argue that they did their part for liberalization and cannot be held responsible for private-sector outcomes. Meanwhile, pro- ponents of results-oriented policies (ROPs) can point to yet another example of how the removal of one barrier led to the formation of a second barrier. -

Group Companies (As of March 31, 2007)

Group Companies (as of March 31, 2007) SUMITOMO MITSUI Financial Group www.smfg.co.jp/english/ The companies under the umbrella of Sumitomo Mitsui Financial Group Company Name: Sumitomo Mitsui Financial Group, Inc. (SMFG) offer diversified financial services centering on banking opera- Business Description: tions, and including leasing, securities and credit card services, and Management of the affairs of banking subsidiaries (under the stipula- information services. tions of the Banking Law) and of non-bank subsidiaries, and ancillary functions Establishment: December 2, 2002 Our Mission Head Office: 1-2, Yurakucho 1-chome, Chiyoda-ku, Tokyo, Japan Chairman of the Board: Masayuki Oku • To provide optimum added value to our customers (Concurrent President at Sumitomo Mitsui Banking Corporation) and together with them achieve growth President: Teisuke Kitayama To create sustainable shareholder value through (Concurrent Chairman of the Board at Sumitomo Mitsui Banking • Corporation) business growth Capital Stock: ¥1,420.9 billion • To provide a challenging and professionally reward- Stock Exchange Listings: ing work environment for our dedicated employees Tokyo Stock Exchange (First Section) Osaka Securities Exchange (First Section) Nagoya Stock Exchange (First Section) www.smbc.co.jp/global/ SUMITOMO MITSUI Banking Corporation Sumitomo Mitsui Banking Corporation (SMBC) Company Name: Sumitomo Mitsui Banking Corporation was established in April 2001 through the merger Business Profile: Banking of two leading banks, The Sakura Bank, Limited Establishment: June 6, 1996 Head Office: 1-2, Yurakucho 1-chome, and The Sumitomo Bank, Limited. In December Credit Ratings (as of July 31, 2007) Chiyoda-ku, Tokyo 2002, Sumitomo Mitsui Financial Group, Inc. was Long-term Short-term established through a stock transfer as a holding President & CEO: Masayuki Oku Moody’s Aa2 P–1 company, under which SMBC became a wholly Number of Employees: 16,407 S&P A+ A–1 Network: Fitch A F1 owned subsidiary. -

CHAPTER 1. Movements During the Pperiod from the Times When the Signs Appeared to May 1956 When Minamata Dsease Was Oficially Dscovered

CHAPTER 1. Movements during the Pperiod from the Times When the Signs Appeared to May 1956 when Minamata Dsease was Oficially Dscovered 1. Background of the times, positioning of Chisso in industrial policy, position of Chisso in economic society of the district, and characteristics of the technological development by Chisso (1) Situation of economy Industrial reconstruction in Japan was proceeded relatively from 1945 onward, early after World War II. Since around 1955, heavy chemical industrialization policy aiming at conversion of energy resources from coal to petroleum has been promoted, and the time when high economic growth of an annual rate of ca. 10% is achieved has arrived. The times of high economic growth lasted until 1973 when the primary oil shock occurred. In the times, Japan pushed on economic growth by the joint efforts of the Government and people with the national aim of increasing international economic competitive force. (2) Position of Chisso in the local economic society A. Location of Chisso in Minamata Minamata situated on the west side of Kyushu faces the Shiranui Sea (Yatsushiro Sea), and the Amakusa Islands are on the opposite shore of the sea. Minamata is adjacent to Kagoshima Prefecture on the most southern tip of Kumamoto Prefecture. The plain at the mouth of the River Minamata running in the center of the city is narrow, and there is a mountain close to the sea. Because of these situations, general traffic means was a sea-based route. In those days of 1898 before the invasion of Chisso, Minamata was a fishing and agrarian village of a total of 2,542 houses. -

The Mineral Industry of Japan in 1998

THE MINERAL INDUSTRY OF JAPAN By John C. Wu Japan’s reserves of limestone, pyrophyllite, and silica are important role in supplying the ferrous and nonferrous metals, quite large. Japan has considerable reserves of coal and iodine, fabricated metal products, and industrial mineral products to but its reserves of natural gas and crude petroleum are very the construction and manufacturing industries of China, small. As a result of exploration conducted in the past 5 years including Hong Kong, Indonesia, the Republic of Korea, by the Metal Mining Agency of Japan (MMAJ), a Malaysia, Singapore, Thailand, and Taiwan. semigovernment agency under the Ministry of International For the first time since the end of World War II, the Japanese Trade and Industry (MITI), reserves of gold, lead, and zinc had economy went into a severe recession in 1998 after 5 years of been extended (Metal Mining Agency of Japan, 1998a), but slow growth in the 1990’s. According to the Economic Japan’s reserves of ferrous and nonferrous minerals are small. Planning Agency and MITI, Japan’s economy, as measured by Japan relied on imports to meet more than 95% of its raw GDP in 1990 constant yen, contracted 2.8% in 1998. material requirements for energy, ferrous metals, and Restructuring in the financial, manufacturing, and other sectors nonferrous metals for its mineral-processing and mineral- had resulted in a substantial increase in unemployment, which related manufacturing sectors. Japan also relied on imports to reached a record rate of 4.1% in 1998. The depressed real meet between 10% and 25% of its requirements for refined estate and stock markets had caused the major banks to carry a nonferrous metal products, industrial mineral products, and heavy load of bad loans, with limited funds available for refined petroleum products. -

Annual Report 2019 Year Ended March 31, 2019

Annual Report 2019 Year ended March 31, 2019 Contributing to the Construction of Social Infrastructure Contents Editorial Policy This “Annual Report” is a publication for the Furukawa Company Group’s About the Furukawa Company Group 1 shareholders and other investors. It is an integrated report that includes financial information from the Group’s “Annual Securities Report” and Furukawa Company Group’s Value Creation Process 2 environmental, social, and governance (ESG)-related information from its “Corporate Governance Report” and “CSR Report.” The intention of this Message from the President 4 Annual Report is to foster a more accurate understanding of the integrated Interview with President Miyakawa 6 thinking, strategies, and actions of the Group while covering the informa- tion necessary for shareholders and other investors. Special Feature ~Improving ROE~ 10 In addition to these report, we disclose financial statements, financial Review of Operations 12 results briefing materials, and post various other information on our corpo- rate website in a timely and appropriate manner. Topics 16 https://www.furukawakk.co.jp/ir/library/ ESG Information The Furukawa Company Group’s ESG Activities 17 Target Period: April 2018–March 2019 CSR Goals 18 (Some activities before and after this period are also included.) Corporate Governance 19 Message from an Outside Independent Director 21 Directors and Audit & Supervisory Board Members 22 Risk Management 23 Annual Report Compliance 24 Environmental Initiatives 25 Environmental Management 26 Annual Securities Corporate Governance CSR Social Initiatives 28 Report Report Report (Financial information) (ESG information) (ESG information) Financial Information Consolidated Six-Year Financial Summary 30 Forward-Looking Statements This Annual Report contains information about the Furukawa Company Group’s Financial Review 31 plans, strategies, and future prospects. -

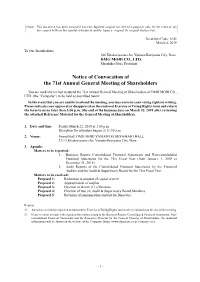

Notice of Convocation of the 71St Annual General Meeting of Shareholders

(Note) This document has been translated from the Japanese original for reference purposes only. In the event of any discrepancy between this translated document and the Japanese original, the original shall prevail. Securities Code: 6141 March 4, 2019 To Our Shareholders 106 Kitakoriyama-cho, Yamato-Koriyama City, Nara DMG MORI CO., LTD. Masahiko Mori, President Notice of Convocation of the 71st Annual General Meeting of Shareholders You are cordially invited to attend the 71st Annual General Meeting of Shareholders of DMG MORI CO., LTD. (the “Company”) to be held as described below. In the event that you are unable to attend the meeting, you may exercise your voting rights in writing. Please indicate your approval or disapproval on the enclosed Exercise of Voting Rights form and return the form to us no later than 5:00 p.m. (the end of the business day) on March 20, 2019 after reviewing the attached Reference Material for the General Meeting of Shareholders. 1. Date and time: Friday, March 22, 2019 at 1:00 p.m. Reception for attendees begins at 11:30 a.m. 2. Venue: Grand Hall, DMG MORI YAMATO KORIYAMAJO HALL 211-3 Kitakoriyama-cho, Yamato-Koriyama City, Nara 3. Agenda: Matters to be reported: 1. Business Report, Consolidated Financial Statements and Non-consolidated Financial Statements for the 71st Fiscal Year (from January 1, 2018 to December 31, 2018) 2. Audit Reports of the Consolidated Financial Statements by the Financial Auditor and the Audit & Supervisory Board for the 71st Fiscal Year Matters to be resolved: Proposal 1: Reduction in amount of capital reserve Proposal 2: Appropriation of surplus Proposal 3: Election of eleven (11) Directors Proposal 4: Election of two (2) Audit & Supervisory Board Members Proposal 5: Revision of remuneration amount for Directors Request ◎ Attendees are kindly requested to submit their Exercise of Voting Rights form to the receptionist on the day of the meeting. -

International Trading Companies: Building on the Japanese Model Robert W

Northwestern Journal of International Law & Business Volume 4 Issue 2 Fall Fall 1982 International Trading Companies: Building on the Japanese Model Robert W. Dziubla Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/njilb Part of the International Law Commons Recommended Citation Robert W. Dziubla, International Trading Companies: Building on the Japanese Model, 4 Nw. J. Int'l L. & Bus. 422 (1982) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Northwestern Journal of International Law & Business by an authorized administrator of Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. Northwestern Journal of International Law & Business International Trading Companies: Building On The Japanese Model Robert W. Dziubla* Passageof the Export Trading Company Act of 1982provides new op- portunitiesfor American business to organize and operate general trading companies. Afterpresenting a thorough history and description of the Japa- nese sogoshosha, Mr. Dziubla gives several compelling reasonsfor Ameri- cans to establish export trading companies. He also examines the changes in United States banking and antitrust laws that have resultedfrom passage of the act, and offers suggestionsfor draftingguidelines, rules, and regula- tionsfor the Export Trading Company Act. For several years, American legislators and businessmen have warned that if America is to balance its international trade-and in particular offset the cost of importing billions of dollars worth of oil- she must take concrete steps to increase her exporting capabilities., On October 8, 1982, the United States took just such a step when President Reagan signed into law the Export Trading Company Act of 1982,2 which provides for the development of international general trading companies similar to the ones used so successfully by the Japanese. -

Whither the Keiretsu, Japan's Business Networks? How Were They Structured? What Did They Do? Why Are They Gone?

IRLE IRLE WORKING PAPER #188-09 September 2009 Whither the Keiretsu, Japan's Business Networks? How Were They Structured? What Did They Do? Why Are They Gone? James R. Lincoln, Masahiro Shimotani Cite as: James R. Lincoln, Masahiro Shimotani. (2009). “Whither the Keiretsu, Japan's Business Networks? How Were They Structured? What Did They Do? Why Are They Gone?” IRLE Working Paper No. 188-09. http://irle.berkeley.edu/workingpapers/188-09.pdf irle.berkeley.edu/workingpapers Institute for Research on Labor and Employment Institute for Research on Labor and Employment Working Paper Series (University of California, Berkeley) Year Paper iirwps-- Whither the Keiretsu, Japan’s Business Networks? How Were They Structured? What Did They Do? Why Are They Gone? James R. Lincoln Masahiro Shimotani University of California, Berkeley Fukui Prefectural University This paper is posted at the eScholarship Repository, University of California. http://repositories.cdlib.org/iir/iirwps/iirwps-188-09 Copyright c 2009 by the authors. WHITHER THE KEIRETSU, JAPAN’S BUSINESS NETWORKS? How were they structured? What did they do? Why are they gone? James R. Lincoln Walter A. Haas School of Business University of California, Berkeley Berkeley, CA 94720 USA ([email protected]) Masahiro Shimotani Faculty of Economics Fukui Prefectural University Fukui City, Japan ([email protected]) 1 INTRODUCTION The title of this volume and the papers that fill it concern business “groups,” a term suggesting an identifiable collection of actors (here, firms) within a clear-cut boundary. The Japanese keiretsu have been described in similar terms, yet compared to business groups in other countries the postwar keiretsu warrant the “group” label least. -

Business Model Innovation and Strategy at Mitsui and Co

MITSUI & CO BUSINESS MODEL INNOVATION AND STRATEGY AT MITSUI & CO. S/N 88-17-027 Mitsui & Co. – Business Model innovation and Strategy at Mitsui & Co. Introduction After successive years of profit, Mitsui & Co’s results in financial year Mar 2016 plunged to a net loss of about USD 834 million1. Its significance is compounded by the fact that it was the first loss ever recorded in recent decade of Mitsui. Is this a sign of more fluctuations of earnings to come, signaling that the general trading strategy traditionally held by Mitsui for decades is on the wrong footing with reality? “I take [this financial loss] very seriously,” said president and chief executive officer (CEO) Tatsuo Yasunaga in his maiden message in Mitsui’s 2016 annual report (Mitsui & Co, 2016, p. 8). Adding to this earning fluctuation concern, Mitsui’s 10-year share price has been flat. As illustrated in Figure A in Appendix A, including dividends and share splits, an investor putting money into Mitsui in 2007 would get a 10-year return-on-investment (ROI) of 8.6percent by 2017. From Appendix C, it is observed in the profit margin percentage chart that net profit margins throughout the 10-year period were around 3.5 percent to 7 percent, ignoring the loss in 2016. With profit margins at these relatively moderate to low levels, Mitsui’s revenue has to improve in order for the profits generated to be grown meaningfully. However, receipts remained relatively flat, with 2016’s end-of-year revenue being approximately the same as that of 2007 at about USD 48 billion. -

I·,;T:A.Chuti-5 S Istutin

THE JAPANESE SOFTWARE INDUSTRY: A COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF SOFTWARE DEVELOPMENT STRATEGY AND TECHNOLOGY OF SELECTED CORPORATIONS by ROBERT W. ARFMAN A.B., Economics Middlebury College (1975) Submitted to the Alfred P. Sloan Schonol of Management and the School of Engineering in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE IN THE MANAGEMENT OF TECHNOLOGY at the MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY May 1988 Copyright Robert W. Arfman 1988 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED The author hereby grants M.I.T. permission to reproduce and to distribute copies of this thesis document in whole or in part. Signatu,- of Author__ Sloan School of Management May 12. 1988 Certified by Michael A. Cusumano Assispant ProAessor of Management Thesis Supervisor Accepted by cPeter P. Gil Acting Director, Management of Technology Program i·,;t:A.CHUTi-5 sISTUTiN O-TFPNW 01WOG1 JUN '3 1988 WARIES THE JAPANESE SOFTWARE INDUSTRY: A COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF SOFTWARE DEVELOPMENT STRATEGY AND TECHNOLOGY OF SELECTED CORPORATIONS by ROBERT W. ARFMAN Submitted to the Alfred P. Sloan School of Management and the School of Engineering on May 12, 1988 in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in the Management of Technology ABSTRACT This thesis discusses the development of the Japanese software industry, beginning with corporate group structures, government support of the computer industry in general and the more recent specific promotion of the software industry and software development process technologies. The SIGMA project is presented in detail followed by a comparative analysis of major Japanese computer manufacturer development process R&D efforts. The current competitive environment is discussed and firms' strategies are compared. -

Knowledge and Power in Occupied Japan: U.S. Censorship of Hiroshima and Nagasaki

Bard College Bard Digital Commons Senior Projects Spring 2018 Bard Undergraduate Senior Projects Spring 2018 Knowledge and Power in Occupied Japan: U.S. Censorship of Hiroshima and Nagasaki May E. Grzybowski Bard College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.bard.edu/senproj_s2018 Part of the Asian History Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Grzybowski, May E., "Knowledge and Power in Occupied Japan: U.S. Censorship of Hiroshima and Nagasaki" (2018). Senior Projects Spring 2018. 134. https://digitalcommons.bard.edu/senproj_s2018/134 This Open Access work is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been provided to you by Bard College's Stevenson Library with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this work in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights- holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Knowledge and Power in Occupied Japan: U.S. Censorship of Hiroshima and Nagasaki Senior Project Submitted to The Division of Social Studies of Bard College by May Grzybowski Annandale-on-Hudson, New York May 2018 Table of Contents Introduction……………………………………………………………………………………………1 Chapter One: Censorship Under SCAP………………………………………………………………..5 Chapter Two: Censored Texts…………………………………………………………..……….…....20 Chapter Three: Effects of Censorship………………………………………………………………...52 Conclusion…………………………………………………………………………………………….66 Bibliography……………………………………………………………………………………...……69 Acknowledgements I would not have been able to finish this project without the support of many people. -

Japan- Tokyo- Office

M A R K E T B E AT TOKYO Office Q4 2020 YoY 12-Mo. Economy Indicates Only Gradual Recovery Chg Forecast The Bank of Japan‘s outlook for real GDP growth rate for FY2020 has been revised downward to -5.6%, 0.1 pp lower than the previous forecast. Total exports value in 2020 declined by 11% y-o-y, the third-largest drop after the GFC in 2009 (-33.1%) and the Plaza Accord in 1986 (-15.9%). -0.14% Exports to China were strong, and total export value in December was up y-o-y for the first time in 25 months. However, global economic recovery is Rental Growth, YoY now expected to be slower due to the re-emergence of COVID-19. In Japan, Capex spending has stopped falling overall in recent month, although 4.22% with variations among industries, and consumer spending has been under increasing downward pressure to face-to-face services. Vacancy Rate Vacancy Rate Trending Up Average Grade A office asking rent in Q4 2020 was JPY37,684, down 1.95% q-o-q. The overall vacancy rate rose 1.13 pp q-o-q to 4.22%, exceeding -1.71% the 4.06% mark of September 2008. Minato Ward, with a concentration of office developments, saw the highest vacancy rise among the five wards of Absorption, QoQ central Tokyo, up 3.49 pp y-o-y to 6%. The vacancy rate in Shinjuku Ward, a hub of SMEs and sales offices, rose 2.88 pp y-o-y to 4.53%, with the ward suspectable to economic shifts.