Remembering 1948 Personal Recollections, Collective Memory, and the Search for “What Really Happened”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Regional Council of Yoav Photo: Lotem Friedland | Design: Kachald

The Regional Council of Yoav Photo: Lotem Friedland | Design: KachalD Tourism Our Vision Hot Springs > Hamei-Yoav Hot Springs is a natural thermo mineral spa. A Municipality composed of multi-generational communities Bet Guvrin > a large national park, which encompasses the sites of an that prosper and renew themselves, maintaining a quality of ancient agricultural settlement of Maresha, and the ancient town of Bet life which guards their specific rural essence, lead by local Guvrin, including many historical caves. Caves of Maresha and Bet Guvrin leadership. recently has inscribed on the World Heritage list by UNESCO. Tending our open spaces and countryside, nature, and the Iron Age sites > One of the largest Iron Age sites in Israel is located in heritage that is special to the Yoav area. Kibbutz Revadim. More than 100 ancient oil presses were discovered there, Excellence in education, fostering culture and social welfare as well as an inscription that clearly identifies the site as Philistine Ekron. services for our residents. Tel Zafit > located inside Tel Zafit National Park. Recent ongoing excavations The joint responsibility of our population and communities for at this Biblical site have produced substantial evidence of siege and security, ecology, and quality of life. subsequent destruction of the site in the late 9th century BC. Fulfillment of our economic potential, and providing quality Sightseeing > Yoav’s magnificent landscapes provide the perfect setting for employment through the development of agriculture, a wide range of leisure activities, such as cycling, hiking, climbing, wine infrastructures, and country tourism, in cooperation with our tasting, gourmet and popular dining, and various festivals such as the neighbouring municipalities renowned Biblical festival. -

Annual Report (PDF)

1 TABLE OF Pulling Together CONTENTS Nowhere did we see a greater display of unity coalescence than in the way AMIT pulled together President’s Message 03 during the pandemic in the early months of 2020. While this annual report will share our proud UNITY in Caring for Our accomplishments in 2019, when the health crisis Most Vulnerable Kids 04 hit, many opportunities arose for unity, which was UNITY in Educational expressed in new and unexpected ways within AMIT. Excellence 05 Since its inception 95 years ago, AMIT has faced its Academy of challenges. Through thick and thin, wars and strife, Entrepreneurship & Innovation 06 and the big hurdles of this small nation, AMIT has been steadfast in its vision and commitment to educate AMIT’s Unique children and create the next generation of strong, Evaluation & Assessment Platform 07 proud, and contributing Israeli citizens. UNITY in Leveling the That Vision Playing Field 08 Has Real Results UNITY in Zionism 09 In 2019, AMIT was voted Israel’s #1 Educational Network for the third year in a row. Our bagrut diploma UNITY in rate climbed to 86 percent, outpacing the national rate Jewish Values 10 of 70 percent. Our students brought home awards Your Impact 11 and accolades in academics, athletics, STEM-centered competitions, and more. Financials 13 And then in the early months of 2020 with the onset Dedications 15 of the pandemic, instead of constricting in fear and uncertainty, AMIT expanded in a wellspring of giving, Board of Directors 16 creativity, and optimism. Students jumped to do chesed Giving Societies 17 to help Israel’s most vulnerable citizens and pivoted to an online distance learning platform during the two months schools were closed. -

Aliyah and Settlement Process?

Jewish Women in Pre-State Israel HBI SERIES ON JEWISH WOMEN Shulamit Reinharz, General Editor Joyce Antler, Associate Editor Sylvia Barack Fishman, Associate Editor The HBI Series on Jewish Women, created by the Hadassah-Brandeis Institute, pub- lishes a wide range of books by and about Jewish women in diverse contexts and time periods. Of interest to scholars and the educated public, the HBI Series on Jewish Women fills major gaps in Jewish Studies and in Women and Gender Studies as well as their intersection. For the complete list of books that are available in this series, please see www.upne.com and www.upne.com/series/BSJW.html. Ruth Kark, Margalit Shilo, and Galit Hasan-Rokem, editors, Jewish Women in Pre-State Israel: Life History, Politics, and Culture Tova Hartman, Feminism Encounters Traditional Judaism: Resistance and Accommodation Anne Lapidus Lerner, Eternally Eve: Images of Eve in the Hebrew Bible, Midrash, and Modern Jewish Poetry Margalit Shilo, Princess or Prisoner? Jewish Women in Jerusalem, 1840–1914 Marcia Falk, translator, The Song of Songs: Love Lyrics from the Bible Sylvia Barack Fishman, Double or Nothing? Jewish Families and Mixed Marriage Avraham Grossman, Pious and Rebellious: Jewish Women in Medieval Europe Iris Parush, Reading Jewish Women: Marginality and Modernization in Nineteenth-Century Eastern European Jewish Society Shulamit Reinharz and Mark A. Raider, editors, American Jewish Women and the Zionist Enterprise Tamar Ross, Expanding the Palace of Torah: Orthodoxy and Feminism Farideh Goldin, Wedding Song: Memoirs of an Iranian Jewish Woman Elizabeth Wyner Mark, editor, The Covenant of Circumcision: New Perspectives on an Ancient Jewish Rite Rochelle L. -

A Christian's Map of the Holy Land

A CHRISTIAN'S MAP OF THE HOLY LAND Sidon N ia ic n e o Zarefath h P (Sarepta) n R E i I T U A y r t s i Mt. of Lebanon n i Mt. of Antilebanon Mt. M y Hermon ’ Beaufort n s a u b s s LEGEND e J A IJON a H Kal'at S Towns visited by Jesus as I L e o n Nain t e s Nimrud mentioned in the Gospels Caesarea I C Philippi (Banias, Paneas) Old Towns New Towns ABEL BETH DAN I MA’ACHA T Tyre A B a n Ruins Fortress/Castle I N i a s Lake Je KANAH Journeys of Jesus E s Pjlaia E u N s ’ Ancient Road HADDERY TYRE M O i REHOB n S (ROSH HANIKRA) A i KUNEITRA s Bar'am t r H y s u Towns visited by Jesus MISREPOTH in K Kedesh sc MAIM Ph a Sidon P oe Merom am n HAZOR D Tyre ic o U N ACHZIV ia BET HANOTH t Caesarea Philippi d a o Bethsaida Julias GISCALA HAROSH A R Capernaum an A om Tabgha E R G Magdala Shave ACHSAPH E SAFED Zion n Cana E L a Nazareth I RAMAH d r Nain L Chorazin o J Bethsaida Bethabara N Mt. of Beatitudes A Julias Shechem (Jacob’s Well) ACRE GOLAN Bethany (Mt. of Olives) PISE GENES VENISE AMALFI (Akko) G Capernaum A CABUL Bethany (Jordan) Tabgha Ephraim Jotapata (Heptapegon) Gergesa (Kursi) Jericho R 70 A.D. Magdala Jerusalem HAIFA 1187 Emmaus HIPPOS (Susita) Horns of Hittin Bethlehem K TIBERIAS R i Arbel APHEK s Gamala h Sea of o Atlit n TARICHAFA Galilee SEPPHORIS Castle pelerin Y a r m u k E Bet Tsippori Cana Shearim Yezreel Valley Mt. -

Liliislittlilf Original Contains Color Illustrations

liliiSlittlilf original contains color illustrations ENERGY 93 Energy in Israel: Data, Activities, Policies and Programs Editors: DANSHILO DAN BAR MASHIAH Dr. JOSEPH ER- EL Ministry of Energy and Infrastructure Jerusalem, 1993 Front Cover: First windfarm in Israel - inaugurated at the Golan Heights, in 1993 The editors wish to thank the Director-General and all other officials concerned, including those from Government companies and institutions in the energy sector, for their cooperation. The contributions of Dr. Irving Spiewak, Nissim Ben-Aderet, Rachel P. Cohen, Yitzhak Shomron, Vladimir Zeldes and Yossi Sheelo (Government Advertising Department) are acknowledged. Thanks are also extended to the Eilat-Ashkelon Pipeline Co., the Israel Electric Corporation, the National Coal Supply Co., Mei Golan - Wind Energy Co., Environmental Technologies, and Lapidot - Israel Oil Prospectors for providing photographic material. TABLE OF CONTENTS OVERVIEW 4 1. ISRAEL'S ENERGY ECONOMY - DATA AND POLICY 8 2. ENERGY AND PEACE 21 3. THE OIL AND GAS SECTOR 23 4. THE COAL SECTOR 29 5. THE ELECTRICITY SECTOR 34 6. OIL AND GAS EXPLORATION. 42 7. RESEARCH, DEVELOPMENT AND DEMONSTRATION 46 8. ENERGY CONSERVATION 55 9. ENERGY AND ENVIRONMENTAL QUALITY. 60 OVERVIEW Since 1992. Israel has been for electricity production. The latter off-shore drillings represer involved, for the first time in its fuel is considered as one of the for sizable oil findings in I: short history, in intensive peace cleanest combustible fuels, and may Oil shale is the only fossil i talks with its neighbors. At the time become a major substitute for have been discovered in Isi this report is being written, initial petroleum-based fuels in the future. -

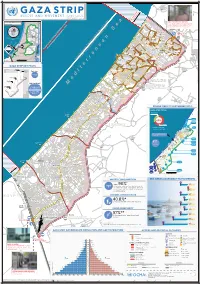

Gaza CRISIS)P H C S Ti P P I U

United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs occupied Palestinian territory Zikim e Karmiya s n e o il Z P m A g l in a AGCCESSA ANDZ AMOV EMENTSTRI (GAZA CRISIS)P h c s ti P P i u F a ¥ SEPTEMBER 2014 o nA P N .5 F 1 Yad Mordekhai EREZ CROSSING (BEIT HANOUN) occupied Palestinian territory: ID a As-Siafa OPEN, six days (daytime) a B?week4 for B?3the4 movement d Governorates e e of international workers and limited number of y h s a b R authorized Palestinians including aid workers, medical, P r 2 e A humanitarian cases, businessmen and aid workers. Jenin d 1 e 0 Netiv ha-Asara P c 2 P Tubas r Tulkarm r fo e S P Al Attarta Temporary Wastewater P n b Treatment Lagoons Qalqiliya Nablus Erez Crossing E Ghaboon m Hai Al Amal r Fado's 4 e B? (Beit Hanoun) Salfit t e P P v i Al Qaraya al Badawiya i v P! W e s t R n m (Umm An-Naser) n i o » B a n k a North Gaza º Al Jam'ia ¹¹ M E D I TER RAN EAN Hatabiyya Ramallah da Jericho d L N n r n r KJ S E A ee o Beit Lahia D P o o J g Wastewater Ed t Al Salateen Beit Lahiya h 5 Al Kur'a J a 9 P l D n Treatment Plant D D D D 9 ) D s As Sultan D 1 2 El Khamsa D " Sa D e J D D l i D 0 D s i D D 0 D D d D D m 2 9 Abedl Hamaid D D r D D l D D o s D D a t D D c Jerusalem D D c n P a D D c h D D i t D D s e P! D D A u P 0 D D D e D D D a l m d D D o i t D D l i " D D n . -

Three Conquests of Canaan

ÅA Wars in the Middle East are almost an every day part of Eero Junkkaala:of Three Canaan Conquests our lives, and undeniably the history of war in this area is very long indeed. This study examines three such wars, all of which were directed against the Land of Canaan. Two campaigns were conducted by Egyptian Pharaohs and one by the Israelites. The question considered being Eero Junkkaala whether or not these wars really took place. This study gives one methodological viewpoint to answer this ques- tion. The author studies the archaeology of all the geo- Three Conquests of Canaan graphical sites mentioned in the lists of Thutmosis III and A Comparative Study of Two Egyptian Military Campaigns and Shishak and compares them with the cities mentioned in Joshua 10-12 in the Light of Recent Archaeological Evidence the Conquest stories in the Book of Joshua. Altogether 116 sites were studied, and the com- parison between the texts and the archaeological results offered a possibility of establishing whether the cities mentioned, in the sources in question, were inhabited, and, furthermore, might have been destroyed during the time of the Pharaohs and the biblical settlement pe- riod. Despite the nature of the two written sources being so very different it was possible to make a comparative study. This study gives a fresh view on the fierce discus- sion concerning the emergence of the Israelites. It also challenges both Egyptological and biblical studies to use the written texts and the archaeological material togeth- er so that they are not so separated from each other, as is often the case. -

He Walked Through the Fields, with His Own Hands , and for Naked Thou Art

MOSHE SHAMIR (Playwright) (1921-2004) was born in Jewish Theatre Collaborative & The Harold Schnitzer Safed, Israel, and spent most of his life in Tel Aviv. He was a Family Program in Judaic Studies present: prolific novelist, journalist, playwright, children’s author, literary critic and political figure. He Walked Through the Israel Onstage: Israeli Society through Drama Fields is based on his own 1947 novel, which was awarded the Ussishkin Prize. Shamir was a member of Kibbutz Mishmar HaEmek from 1944 to 1946 A member of the He Walked Palmach, in 1948, he founded the soldiers` weekly, Bamahaneh, and was its first editor. He edited it until he Through the Fields was dismissed at the request of David Ben-Gurion for By Moshe Shamir publishing an article about a celebration of the disbanding of Palmach . He served on the editorial board of the daily Maariv in the 50s. Shamir was a member of Knesset, the Israeli Parliament, from 1977 to 1981, his politics shifting from Mapam (labor) to Likud to participating in the founding of Tehiya, after the Camp David Treaty of 1979. The most prominent representative of his generation of writers Shamir was awarded the Bialik Prize (1955), the Israel Prize (1988) and the ACUM Prize for Lifetime Achievement (2002). His best known historical novels include The King of Flesh and Blood and David’s Stranger. His best known topical works are He Walked through the Fields, With His Own Hands , and For Naked Thou Art . His books generally deal with contemporary problems of Israel as seen from the viewpoint of the younger generation. -

Memory Trace Fazal Sheikh

MEMORY TRACE FAZAL SHEIKH 2 3 Front and back cover image: ‚ ‚ 31°50 41”N / 35°13 47”E Israeli side of the Separation Wall on the outskirts of Neve Yaakov and Beit Ḥanīna. Just beyond the wall lies the neighborhood of al-Ram, now severed from East Jerusalem. Inside front and inside back cover image: ‚ ‚ 31°49 10”N / 35°15 59”E Palestinian side of the Separation Wall on the outskirts of the Palestinian town of ʿAnata. The Israeli settlement of Pisgat Ze’ev lies beyond in East Jerusalem. This publication takes its point of departure from Fazal Sheikh’s Memory Trace, the first of his three-volume photographic proj- ect on the Israeli–Palestinian conflict. Published in the spring of 2015, The Erasure Trilogy is divided into three separate vol- umes—Memory Trace, Desert Bloom, and Independence/Nakba. The project seeks to explore the legacies of the Arab–Israeli War of 1948, which resulted in the dispossession and displacement of three quarters of the Palestinian population, in the establishment of the State of Israel, and in the reconfiguration of territorial borders across the region. Elements of these volumes have been exhibited at the Slought Foundation in Philadelphia, Storefront for Art and Architecture, the Brooklyn Museum of Art, and the Pace/MacGill Gallery in New York, and will now be presented at the Al-Ma’mal Foundation for Contemporary Art in East Jerusalem, and the Khalil Sakakini Cultural Center in Ramallah. In addition, historical documents and materials related to the history of Al-’Araqīb, a Bedouin village that has been destroyed and rebuilt more than one hundred times in the ongoing “battle over the Negev,” first presented at the Slought Foundation, will be shown at Al-Ma’mal. -

Israel I Palestina Diversos Territoris, Dues Nacions I Una Disputa

Israel i Palestina Diversos territoris, dues nacions i una disputa Arret d’Arreug i Pau Treball de Recerca Octubre de 2020 2n de Batxillerat Israel i Palestina: Diversos territoris, dues nacions i una disputa ÍNDEX AGRAÏMENTS 5 OBJECTIUS 6 INTRODUCCIÓ 7 BLOC I: DE L’ORIGEN A LA VIOLÈNCIA 9 1. CONTEXT HISTÒRIC 10 1.1. L’estima jueu cap a l’anomenada terra promesa 11 1.2. Judea, província romana 15 1.3. Els Àrabs, les Croades i l’Imperi Otomà 16 1.4. El Sionisme original 17 1.5. El Sionisme polític 18 2. ISRAEL, DE NACIÓ A PAÍS 20 2.1. Introducció 21 2.2. Un origen envoltat de conflictes 22 2.3. El “mes cruel” 24 2.4. Els britànics es plantegen cedir el protectorat 25 2.5. Batalla de Haifa 26 3. ISRAEL, UNA QÜESTIÓ INTERNACIONAL 27 3.1. Predeclaració d’independència israelí 28 3.2. Proclamació d’independència d’Israel 28 3.3. Conflictes postindependència 29 3.4. Entrada d’Egipte a la guerra 30 3.5. Jerusalem al maig del 48 31 3.6. Finals de maig 32 3.7. Gran aturament del foc del 48 33 3.8. La primera treva (juny del 48) 33 3.9. L’Altalena 34 3.10. Expansions després de la unificació jueva 34 3.11. Lod i Ramla 35 3.12. Folke Bernadotte, mediador de l’ONU 36 3.13. Nègueb I 37 3.14. Operació Hiram 37 2 Israel i Palestina: Diversos territoris, dues nacions i una disputa 3.15. Nègueb II 38 3.16. -

The Tunnels in Gaza February 2015 the Tunnels in Gaza Testimony Before the UN Commission of Inquiry on the 2014 Gaza Conflict Dr

Dr. Eado Hecht 1 The Tunnels in Gaza February 2015 The Tunnels in Gaza Testimony before the UN Commission of Inquiry on the 2014 Gaza Conflict Dr. Eado Hecht The list of questions is a bit repetitive so I have decided to answer not directly to each question but in a comprehensive topical manner. After that I will answer specifically a few of the questions that deserve special emphasis. At the end of the text is an appendix of photographs, diagrams and maps. Sources of Information 1. Access to information on the tunnels is limited. 2. I am an independent academic researcher and I do not have access to information that is not in the public domain. All the information is based on what I have gleaned from unclassified sources that have appeared in the public media over the years – listing them is impossible. 3. The accurate details of the exact location and layout of all the tunnels are known only by the Hamas and partially by Israeli intelligence services and the Israeli commanders who fought in Gaza last summer. 4. Hamas, in order not to reveal its secrets to the Israelis, has not released almost any information on the tunnels themselves except in the form of psychological warfare intended to terrorize Israeli civilians or eulogize its "victory" for the Palestinians: the messages being – the Israelis did not get all the tunnels and we are digging more and see how sophisticated our tunnel- digging operation is. These are carefully sanitized so as not to reveal information on locations or numbers. -

By Nathan Shaham

"Tracing Back my Own Footsteps": Space, Walking and Memory in "Shiv'a Mehem" by Nathan Shaham Ayala Amir Absract This article focuses on Natan Shaham's short story "Shiva Mehem" ("Seven of Them"). Written in 1948, the story presents the moral dilemma faced by a group of warriors caught in a minefield. Combining insights from various discourses (ecocriticism, postcolonialism and the emerging field of geocriticism), the article explores the theme of walking both in the story and in the wider context of Shaham's writing and the ideology of the 1948 generation. The exploration of the various aspect of the story's main image, the landmine and its effect on the body's movement in space, leads to viewing the mine image as a thematic and formal nexus connecting time and space, personal and historical time, past memory and the present. Through this powerful image that conveys the experience of the generation facing life in their own sovereign state, "Shiva Mehem" also illustrates the deep connection between Shaham's writing and his movement in or upon the land, both as a writer and as a warrior. I. Walking I will begin by bringing together three writers who reflect on the nature of walking. The first, a writer, philosopher, naturalist and walker, the prophet of today's environmental thinking, Henry David Thoreau, writes in his essay "Walking": I have met with but one or two persons in the course of my life who understood the art of Walking, that is, of taking walks,—who had a genius, so to speak, for sauntering: which word is beautifully derived “from idle people who roved about the country, in the Middle Ages, and asked charity, under pretence of going à la Sainte Terre,” to the Holy Land, till the children exclaimed, “There goes a Sainte-Terrer,” 1 a Saunterer,—a Holy-Lander […] Some, however, would derive the word from sans terre, without land or a home, which, therefore, in the good sense, will mean, having no particular home, but equally at home everywhere.