First Record of the White-Collared Swift in California

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tinamiformes – Falconiformes

LIST OF THE 2,008 BIRD SPECIES (WITH SCIENTIFIC AND ENGLISH NAMES) KNOWN FROM THE A.O.U. CHECK-LIST AREA. Notes: "(A)" = accidental/casualin A.O.U. area; "(H)" -- recordedin A.O.U. area only from Hawaii; "(I)" = introducedinto A.O.U. area; "(N)" = has not bred in A.O.U. area but occursregularly as nonbreedingvisitor; "?" precedingname = extinct. TINAMIFORMES TINAMIDAE Tinamus major Great Tinamou. Nothocercusbonapartei Highland Tinamou. Crypturellus soui Little Tinamou. Crypturelluscinnamomeus Thicket Tinamou. Crypturellusboucardi Slaty-breastedTinamou. Crypturellus kerriae Choco Tinamou. GAVIIFORMES GAVIIDAE Gavia stellata Red-throated Loon. Gavia arctica Arctic Loon. Gavia pacifica Pacific Loon. Gavia immer Common Loon. Gavia adamsii Yellow-billed Loon. PODICIPEDIFORMES PODICIPEDIDAE Tachybaptusdominicus Least Grebe. Podilymbuspodiceps Pied-billed Grebe. ?Podilymbusgigas Atitlan Grebe. Podicepsauritus Horned Grebe. Podicepsgrisegena Red-neckedGrebe. Podicepsnigricollis Eared Grebe. Aechmophorusoccidentalis Western Grebe. Aechmophorusclarkii Clark's Grebe. PROCELLARIIFORMES DIOMEDEIDAE Thalassarchechlororhynchos Yellow-nosed Albatross. (A) Thalassarchecauta Shy Albatross.(A) Thalassarchemelanophris Black-browed Albatross. (A) Phoebetriapalpebrata Light-mantled Albatross. (A) Diomedea exulans WanderingAlbatross. (A) Phoebastriaimmutabilis Laysan Albatross. Phoebastrianigripes Black-lootedAlbatross. Phoebastriaalbatrus Short-tailedAlbatross. (N) PROCELLARIIDAE Fulmarus glacialis Northern Fulmar. Pterodroma neglecta KermadecPetrel. (A) Pterodroma -

AOS Classification Committee – North and Middle America Proposal Set 2018-B 17 January 2018

AOS Classification Committee – North and Middle America Proposal Set 2018-B 17 January 2018 No. Page Title 01 02 Split Fork-tailed Swift Apus pacificus into four species 02 05 Restore Canada Jay as the English name of Perisoreus canadensis 03 13 Recognize two genera in Stercorariidae 04 15 Split Red-eyed Vireo (Vireo olivaceus) into two species 05 19 Split Pseudobulweria from Pterodroma 06 25 Add Tadorna tadorna (Common Shelduck) to the Checklist 07 27 Add three species to the U.S. list 08 29 Change the English names of the two species of Gallinula that occur in our area 09 32 Change the English name of Leistes militaris to Red-breasted Meadowlark 10 35 Revise generic assignments of woodpeckers of the genus Picoides 11 39 Split the storm-petrels (Hydrobatidae) into two families 1 2018-B-1 N&MA Classification Committee p. 280 Split Fork-tailed Swift Apus pacificus into four species Effect on NACC: This proposal would change the species circumscription of Fork-tailed Swift Apus pacificus by splitting it into four species. The form that occurs in the NACC area is nominate pacificus, so the current species account would remain unchanged except for the distributional statement and notes. Background: The Fork-tailed Swift Apus pacificus was until recently (e.g., Chantler 1999, 2000) considered to consist of four subspecies: pacificus, kanoi, cooki, and leuconyx. Nominate pacificus is highly migratory, breeding from Siberia south to northern China and Japan, and wintering in Australia, Indonesia, and Malaysia. The other subspecies are either residents or short distance migrants: kanoi, which breeds from Taiwan west to SE Tibet and appears to winter as far south as southeast Asia. -

Partial Migration in the Mediterranean Storm Petrel Hydrobates Pelagicus Melitensis

Lago et al.: Partial migration in Mediterranean Storm Petrel 105 PARTIAL MIGRATION IN THE MEDITERRANEAN STORM PETREL HYDROBATES PELAGICUS MELITENSIS PAULO LAGO*, MARTIN AUSTAD & BENJAMIN METZGER BirdLife Malta, 57/28 Triq Abate Rigord, Ta’ Xbiex XBX 1120, Malta *([email protected]) Received 27 November 2018, accepted 05 February 2019 ABSTRACT LAGO, P., AUSTAD, M. & METZGER, B. 2019. Partial migration in the Mediterranean Storm Petrel Hydrobates pelagicus melitensis. Marine Ornithology 47: 105–113. Studying the migration routes and wintering areas of seabirds is crucial to understanding their ecology and to inform conservation efforts. Here we present results of a tracking study carried out on the little-known Mediterranean Storm Petrel Hydrobates pelagicus melitensis. During the 2016 breeding season, Global Location Sensor (GLS) tags were deployed on birds at the largest Mediterranean colony: the islet of Filfla in the Maltese Archipelago. The devices were retrieved the following season, revealing hitherto unknown movements and wintering areas of this species. Most individuals remained in the Mediterranean throughout the year, with birds shifting westwards or remaining in the central Mediterranean during winter. However, one bird left the Mediterranean through the Strait of Gibraltar and wintered in the North Atlantic. Our results from GLS tracking, which are supported by data from ringed and recovered birds, point toward a system of partial migration with high inter-individual variation. This highlights the importance of trans-boundary marine protection for the conservation of vulnerable seabirds. Key words: Procellariformes, movement, geolocation, wintering, Malta, capture-mark-recovery INTRODUCTION The Mediterranean Storm Petrel has been described as sedentary, because birds are present in their breeding areas throughout the year The Mediterranean Storm Petrel Hydrobates pelagicus melitensis is (Zotier et al. -

Best Management Practices for Excluding Barn Swallows and Chimney Swifts from Buildings and Structures

Best Management Practices for Excluding Barn Swallows and Chimney Swifts from Buildings and Structures Photo: R. Kimpel (flickr.com/creative commons) ontario.ca/speciesatrisk BLEED Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry 2017 Suggested Citation Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry. 2017 Best Management Practices for Excluding Barn Swallows and Chimney Swifts from Buildings and Structures. Queen’s Printer for Ontario, 2017. 22 pp. Authors This document was prepared by Debbie Badzinski, Brandon Holden and Sean Spisani of Stantec Consulting Ltd. and Kristyn Richardson of Bird Studies Canada on behalf of the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry. Acknowledgements The project team wishes to acknowledge the following individuals for providing guidance and review of this document: ´ Todd Copeland, Darlene Dove, Lauren Kruschenske, Megan McAndrew, Kerry Reed, Chris Risley, Lara Griffin and Erin Thompson Seabert from the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry ´ Larry Sarris from the Ontario Ministry of Transportation ´ Nicole Kopysh from Stantec Consulting Ltd. This document includes best available information as of the date of publication and will be updated as new information becomes available. If you are interested in providing information for consideration in updates of this document, please email [email protected]. Page 1 | Best Management Practices for Excluding Barn Swallows and Chimney Swifts from Buildings and Structures 1.0 Introduction & Purpose ..........................................................................................3 -

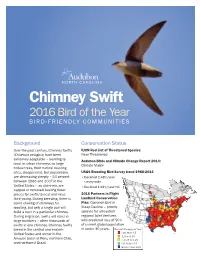

Chimney Swift 2016 Bird of the Year BIRD-FRIENDLY COMMUNITIES

Chimney Swift 2016 Bird of the Year BIRD-FRIENDLY COMMUNITIES Background Conservation Status Over the past century, Chimney Swifts IUCN Red List of Threatened Species: (Chaetura pelagica) have been Near Threatened extremely adaptable – learning to Audubon Birds and Climate Change Report 2014: roost in urban chimneys as large Climate Stable hollow trees, their natural roosting sites, disappeared. But populations USGS Breeding Bird Survey trend 1966-2013 are decreasing steeply – 53 percent •Declined 2.48%/year between 1966 and 2007 in the survey-wide United States – as chimneys are •Declined 1.61%/year NC capped or removed, leaving fewer places for swifts to nest and raise 2016 Partners in Flight their young. During breeding, there is Landbird Conservation some sharing of chimneys for Plan: Common Bird in roosting, but only a single pair will Steep Decline – priority build a nest in a particular chimney. species for all eastern During migration, swifts will roost in regional Joint Ventures large numbers – often thousands of with predicted loss of 50% swifts in one chimney. Chimney Swifts of current global population breed in the central and eastern in under 30 years. Percent Change per Year United States and winter in the Less than 1.5 -1.5 to -0.25 Amazon basin of Peru, northern Chile, > -0.25 to 0.25 and northwest Brazil. > 0.25 to +1.5 Greater than +1.5 Four Ways You Can Help 1 Keep Your Chimney Open The practice of capping older chimneys makes 2 them inaccessible to swifts. One solution is to Be a Citizen hire a chimney sweep to Scientist cap the chimney in Report nesting and 3 November and open it up roosting sites at again before Chimney Construct A nc.audubon.org. -

Foraging Habitat Selection and Seasonality of Breeding in Germain's Swiftlet (Aerodramus Inexpectatus Germani) in Southern Thailand

Foraging Habitat Selection and Seasonality of Breeding in Germain's Swiftlet (Aerodramus inexpectatus germani) in Southern Thailand Nutjarin Petkliang A Thesis Submitted in Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Doctor of Philosophy in Biology Prince of Songkla University 2017 Copyright of Prince of Songkla University i Foraging Habitat Selection and Seasonality of Breeding in Germain's Swiftlet (Aerodramus inexpectatus germani) in Southern Thailand Nutjarin Petkliang A Thesis Submitted in Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Doctor of Philosophy in Biology Prince of Songkla University 2017 Copyright of Prince of Songkla University ii Thesis Title Foraging Habitat Selection and Seasonality of Breeding in Germain’s Swiftlet (Aerodramus inexpectatus germani) in Southern Thailand Author Mrs. Nutjarin Petkliang Major Program Biology Major Advisor Examining Committee : .............................................................. ...........................................Chairperson (Assist. Prof. Dr. Sara Bumrungsri) (Assoc. Prof. Philip David Round) Co-advisor .............................................Committee (Assoc. Prof. Dr. George Andrew Gale) .............................................................. (Assoc. Prof. Dr. George Andrew Gale) .............................................Committee (Assist. Prof. Dr. Sara Bumrungsri) .............................................Committee (Dr. Sopark Jantarit) The Graduate School, Prince of Songkla University, has approved this thesis as fulfillment of the requirements for Doctor -

Apodiformes: Apodidae) Breeding Near Presidente Figueiredo, Amazonas: the First Documented Record for Brazil

Revista Brasileira de Ornitologia, 16(4):398-401 NOTA dezembro de 2008 The White-chinned Swift Cypseloides cryptus (Apodiformes: Apodidae) breeding near Presidente Figueiredo, Amazonas: the first documented record for Brazil Andrew Whittaker and Steven Araújo Whittaker Conjunto Acariquara Sul. Rua Samaumas 214, 69085-410, Manaus, AM, Brasil. E-mails: [email protected] e [email protected] Recebido em 15/01/2008. Aceito em 22/09/2008. RESUMO: O taperuçu Cypseloides cryptus (Apodiformes: Apodidae) nidificando perto de Presidente Figueiredo, Amazonas: primeiro registro documentado para o Brasil. O pouco conhecido Cypseloides cryptus Zimmer, 1945 foi encontrado nidificando em duas cachoeiras situadas em locais diferentes perto de Presidente Figueiredo em julho de 2007. Um ninho predado foi coletado e depositado na coleção de aves do INPA e no outro ninho o filhote foi manipulado, medido e fotografado e colocado de volta em seu ninho. Estes registros estendem para o sul a distribuição conhecida cerca de 700 km a partir dos tepuis do sudeste da Venezuela e sudeste da Guiana. O nome sugerido para a espécie em português é Taperuçu-do-mento-branco. PALAVras-CHAVE: Amazonas, Apodidae, Brasil, cachoeira, Cypseloides cryptus, nidificação, Taperuçu-do-mento-branco, nidificação, cachoeira. KEY-WORDS: Amazonas, Apodidae, Brazil, breeding, Cypseloides cryptus, waterfall, White-chinned Swift. The distribution of the White-chinned Swift Cypsel- AW’s knowledge of the distributions of all know oides cryptus Zimmer, 1945 is poorly known with scattered Brazilian Cypseloides suggested that this record could per- records from both Central and South America. In Cen- tain to the poorly-known White-chinned Swift, which tral America records primarily originate from the Carib- had not yet been documented in Brazil, although known bean slope and lowlands of Belize, Honduras, Nicaragua, to occur and breed further north in the Guianan Shield Costa Rica and Panama. -

The Common Swift Apus Apus—A New Bird for Sri Lanka

Correspondence 195 appearance and size, and its double-pointed casque with black false&gp=false&ev=Z&mr=1-12&bmo=1&emo=12&yr=all&byr=1900&eyr=2020. rim in front. It was feeding on a Ficus tree. Soon a female Great [Accessed on 05 August 2020.] Hornbill was also seen on the same tree [206]. They stayed there eBird. 2020b: Siberian Rubythroat Calliope calliope. Website URL: https://ebird.org/ map/sibrub?neg=true&env.minX=&env.minY=&env.maxX=&env.maxY=&zh=fa for few minutes and then flew away. The species was not seen lse&gp=false&ev=Z&mr=1-12&bmo=1&emo=12&yr=all&byr=1900&eyr=2020. on the subsequent visits to the national park. [Accessed on 05 August 2020.] eBird. 2020c. Rufous Woodpecker Micropternus brachyurus. Website URL: https://ebird.org/map/rufwoo2?neg=true&env.minX=&env. minY=&env.maxX=&env.maxY=&zh=false&gp=false&ev=Z&mr=1- 12&bmo=1&emo=12&yr=all&byr=1900&eyr=2020. [Accessed on 05 August 2020.] eBird. 2020d. Great Hornbill Buceros bicornis. Website URL: https://ebird.org/map/ grehor1?neg=true&env.minX=&env.minY=&env.maxX=&env.maxY=&zh=false&gp =false&ev=Z&mr=1-12&bmo=1&emo=12&yr=all&byr=1900&eyr=2020 [Accessed on 05 August 2020.] Grimmett, R., Inskipp, C., & Inskipp, T., 1998. Birds of the Indian Subcontinent. 1st ed. London: Christopher Helm, A & C Black. Pp. 1–888. Grimmett, R., Inskipp, C., & Inskipp, T., 2011. Birds of the Indian Subcontinent. 2nd ed. -

277 Common Swift Put Your Logo Here

Javier Blasco-Zumeta & Gerd-Michael Heinze Sponsor is needed. Write your name here Put your logo here 277 Common Swift Pallid Swift Common Swift. Adult (13-VII). SEXING COMMON SWIFT (Apus apus ) Plumage of both sexes alike. IDENTIFICATION AGEING 14-16 cm. Plumage blackish brown; with some 4 age groups can be recognized: greenish gloss on upperparts; whitish throat; Juvenile with feathers on body, wing and tail long wings; forked tail. edged white; outermost tail feather with both webs rounded and curved. CAUTION: in late summer some birds have lost much of their whi- te edging by wear. 2nd year similar to adult , but recognizable by retained juvenile flight feathers and wing co- verts, which will be very worn; outermost tail feather more rounded than in adults but less than in juveniles (CAUTION: this characteris- tic is not always useful due to overlap). 3rd year only in birds which have retained Common Swift. Pattern of juvenile 10th primay, which will be very throat, tail and strongly worn and reduced to the shaft. flank. Adult with plumage without white edges; flight feathers and wing coverts less worn than in 2nd year ; if outer primaries retained, then SIMILAR SPECIES brownish and worn contrasting with the Can recall a Barn Swallow , which has white neighbouring moulted feathers; outermost tail underparts and buff throat and forehead. Pallid feather with both webs straight. Swift has bigger pale patch on throat, flanks with pale streaked, no so black plumage and less forked tail. Common Barn Swift. Ageing. Swallow Pattern of a wing covert: left adult; right juvenile. -

VANIKORO SWIFTLET Aerodramus Vanikorensisbartschi

RECOVERY PLAN Maxima Islands Population of the VANIKORO SWIFTLET Aerodramus vanikorensisbartschi U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR FISH AND WILDLIFE SERVICE RegionOne, Portland, Oregon September1992 Recovery Plan for the Mariana Islands Population of the Vanikoro Swiftiet, Aerodramus vanikorensis bartschi Published by: U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service Portland, Oregon Approved: Regional Director, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service 7-ro -9/ Date• THIS IS THE COMPLETED VANIKORO SWIFTLET RECOVERY PLAN. IT DELINEATES REASONABLE ACTIONS WHICH ARE BELIEVED TO BE REQUIRED TO RECOVER AND/OR PROTECT THE SPECIES. OBJECTIVES WILL BE ATTAINED AND ANY NECESSARY FUNDS MADE AVAILABLE SUBJECT TO BUDGETARY AND OTHER CONSTRAINTS AFFECTING THE PARTIES INVOLVED, AS WELL AS THE NEED TO ADDRESS OTHER PRIORITIES. THIS RECOVERY PLAN DOES NOT NECESSARILY REPRESENT OFFICIAL POSITIONS OR APPROVALS OF THE COOPERATING AGENCIES, AND IT DOES NOT NECESSARILY REPRESENT THE VIEWS OF ALL INDIVIDUALS WHO PLAYED A ROLE IN PREPARING THIS PLAN. IT IS SUBJECT TO MODIFICATION AS DICTATED BY NEW FINDINGS, CHANGES IN SPECIES STATUS, AND COMPLETION OF TASKS DESCRIBED IN THE PLAN. Literature Citation: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 1991. Recovery Plan for the Mariana Islands Population of the Vanikoro Swiftlet, Aerodramus vanikorensis bartschi U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Portland, OR. 49 pp. ADDITIONAL COPIES MAY BE PURCHASED FROM Fish and Wildlife Reference Service 5430 Grosvenor Lane, Suite 110 Bethesda, Maryland 20814 301/492-6403 or 1-800-582-3421 The fee for the Plan varies depending on the number of pages of the Plan. i . ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The Vanikoro Swiftlet Recovery Plan was prepared by the Honolulu Field Office of the U.S. -

Migration Dynamics and Directional Preferences of Passerine Migrants in Azraq (E Jordan) in Spring 2008

THE RING 33, 1-2 (2011) DOI 10.2478/v10050-011-0001-9 MIGRATION DYNAMICS AND DIRECTIONAL PREFERENCES OF PASSERINE MIGRANTS IN AZRAQ (E JORDAN) IN SPRING 2008 Katarzyna Stêpniewska, Ashraf El-Hallah and Przemys³aw Busse ABSTRACT Stêpniewska K., El-Hallah A., Busse P. 2011. Migration dynamics and directional prefer- ences of passerine migrants in Azraq (E Jordan) in spring 2008. Ring 33, 1-2: 3-25. Azraq ringing station is located in the Azraq Wetland Reserve in the eastern part of Jordan, on the Eastern Palearctic Flyway. It covers different types of habitat: reedbeds and a dry area with tamarisks (Tamarix sp.) and nitre bushes (Nitraria billardierei). In total, from 18 March till 28 April 2008, we caught 2767 birds from 64 species. Three species dominated distinctly, constituting 58% of total number of caught birds: the Reed Warbler (Acrocepha- lus scirpaceus) – 570, the Chiffchaff (Phylloscopus collybita) – 535 and the Lesser Whitethroat (Sylvia curruca) – 488 birds. The catching dynamics reveals the highest num- bers of birds in the beginning of the studied period. The total number constantly decreased till 6 April and then subsequently increased. The first high peak of the dynamics at the end of March was due to intensive migration of Chiffchaffs and Lesser Whitethroats. The se- cond one at the end of April was caused by pronounced migration of Reed Warblers and Blackcaps. High numbers of migrants in the beginning and at the end of the catching pe- riod reveal that we did not cover the whole migration season in Azraq, so it is necessary to begin the study much earlier and to finish later there. -

Northern Goshawk Surveys on the Beartooth, Ashland, and Sioux Districts of the Custer Gallatin National Forest: 2012‐2014

Northern Goshawk Surveys on the Beartooth, Ashland, and Sioux Districts of the Custer Gallatin National Forest: 2012‐2014 Prepared for: Custer‐Gallatin National Forest Prepared by: Bryce A. Maxell Montana Natural Heritage Program a cooperative program of the Montana State Library and the University of Montana February 2016 Northern Goshawk Surveys on the Beartooth, Ashland, and Sioux Districts of the Custer Gallatin National Forest: 2012‐2014 Prepared for: Custer‐Gallatin National Forest 10 East Babcock Bozeman, MT 59771 Agreement Numbers: 09‐CS‐11015600‐054 12‐CS‐11015600‐056 Prepared by: Bryce A. Maxell © 2016 Montana Natural Heritage Program P.O. Box 201800 • 1515 East Sixth Avenue • Helena, MT 59620‐1800 • 406‐444‐3290 _____________________________________________________________________________________ This document should be cited as follows: Maxell, B.A. 2016. Northern Goshawk surveys on the Beartooth, Ashland, and Sioux Districts of the Custer Gallatin National Forest: 2012‐2014. Report to Custer Gallatin National Forest. Montana Natural Heritage Program, Helena, Montana 65 pp. plus appendices. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Forest Service contracted with the Ashland, and Sioux Districts, including 38 Montana Natural Heritage Program to conduct detections of Northern Goshawks and 230 surveys for the Northern Goshawk (Accipter detections of 25 other Montana and South gentilis) between 2012 and 2014 to inform Dakota species of conservation concern. forest and project planning efforts on the Beartooth, Ashland and Sioux Districts. The Despite our efforts, four units on the Beartooth, major goals were to: (1) provide more Ashland, and Sioux Districts still stand out as widespread baseline survey coverage for being in need of baseline call playback surveys Northern Goshawk; (2) conduct bird point count for Northern Goshawk.