MARINE DEBRIS POLLUTION in the PACIFIC Literature Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FISH LIST WISH LIST: a Case for Updating the Canadian Government’S Guidance for Common Names on Seafood

FISH LIST WISH LIST: A case for updating the Canadian government’s guidance for common names on seafood Authors: Christina Callegari, Scott Wallace, Sarah Foster and Liane Arness ISBN: 978-1-988424-60-6 © SeaChoice November 2020 TABLE OF CONTENTS GLOSSARY . 3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY . 4 Findings . 5 Recommendations . 6 INTRODUCTION . 7 APPROACH . 8 Identification of Canadian-caught species . 9 Data processing . 9 REPORT STRUCTURE . 10 SECTION A: COMMON AND OVERLAPPING NAMES . 10 Introduction . 10 Methodology . 10 Results . 11 Snapper/rockfish/Pacific snapper/rosefish/redfish . 12 Sole/flounder . 14 Shrimp/prawn . 15 Shark/dogfish . 15 Why it matters . 15 Recommendations . 16 SECTION B: CANADIAN-CAUGHT SPECIES OF HIGHEST CONCERN . 17 Introduction . 17 Methodology . 18 Results . 20 Commonly mislabelled species . 20 Species with sustainability concerns . 21 Species linked to human health concerns . 23 Species listed under the U .S . Seafood Import Monitoring Program . 25 Combined impact assessment . 26 Why it matters . 28 Recommendations . 28 SECTION C: MISSING SPECIES, MISSING ENGLISH AND FRENCH COMMON NAMES AND GENUS-LEVEL ENTRIES . 31 Introduction . 31 Missing species and outdated scientific names . 31 Scientific names without English or French CFIA common names . 32 Genus-level entries . 33 Why it matters . 34 Recommendations . 34 CONCLUSION . 35 REFERENCES . 36 APPENDIX . 39 Appendix A . 39 Appendix B . 39 FISH LIST WISH LIST: A case for updating the Canadian government’s guidance for common names on seafood 2 GLOSSARY The terms below are defined to aid in comprehension of this report. Common name — Although species are given a standard Scientific name — The taxonomic (Latin) name for a species. common name that is readily used by the scientific In nomenclature, every scientific name consists of two parts, community, industry has adopted other widely used names the genus and the specific epithet, which is used to identify for species sold in the marketplace. -

An Assessment Report on Microplastics

An Assessment Report on Microplastics This document was prepared by B Stevens, North Carolina Coastal Federation Table of Contents What are Microplastics? 2 Where Do Microplastics Come From? 3 Primary Sources 3 Secondary Sources 5 What are the Consequences of Microplastics? 7 Marine Ecosystem Health 7 Water Quality 8 Human Health 8 What Policies/Practices are in Place to Regulate Microplastics? 10 Regional Level 10 Outer Banks, North Carolina 10 Other United States Regions 12 State Level 13 Country Level 14 United States 14 Other Countries 15 International Level 16 Conventions 16 Suggested World Ban 17 International Campaigns 18 What Solutions Already Exist? 22 Washing Machine Additives 22 Faucet Filters 23 Advanced Wastewater Treatment 24 Plastic Alternatives 26 What Should Be Done? 27 Policy Recommendations for North Carolina 27 Campaign Strategy for the North Carolina Coastal Federation 27 References 29 1 What are Microplastics? The category of ‘plastics’ is an umbrella term used to describe synthetic polymers made from either fossil fuels (petroleum) or biomass (cellulose) that come in a variety of compositions and with varying characteristics. These polymers are then mixed with different chemical compounds known as additives to achieve desired properties for the plastic’s intended use (OceanCare, 2015). Plastics as litter in the oceans was first reported in the early 1970s and thus has been accumulating for at least four decades, although when first reported the subject drew little attention and scientific studies focused on entanglements, ‘ghost fishing’, and ingestion (Andrady, 2011). Today, about 60-90% of all marine litter is plastic-based (McCarthy, 2017), with the total amount of plastic waste in the oceans expected to increase as plastic consumption also increases and there remains a lack of adequate reduce, reuse, recycle, and waste management tactics across the globe (GreenFacts, 2013). -

Recent Data of Maximum Age and Length of Painted Comber Serranus Scriba (Linnaeus, 1758) in Mediterranean Sea

ISSN: 0001-5113 ACTA ADRIAT., UDC: 594.1 (497.5) (262.3) AADRAY 51(2): 223 - 226, 2010 Recent data of maximum age and length of painted comber Serranus scriba (Linnaeus, 1758) in Mediterranean Sea Barbara ZORICA*, Armin PALLAORO, Gorenka SINOVČIĆ and Vanja ČIKEŠ KEČ Institute of Oceanography and Fisheries, P.O. Box 500, 21 000 Split, Croatia *Corresponding author, e-mail: [email protected] The present study was undertaken not only to register the new recently noticed maximum age and total length of Serranus scriba (Linnaeus, 1758), contributing to the knowledge of this species in the Mediterranean and Adriatic Sea inclusively. A painted comber specimen of 323 mm of total length and age 16 years was caught during August 2008 in the Lavdra Channel (middle-eastern Adriatic Sea). Key words: Serranus scriba, Serranidae, maximum length, maximum age, Adriatic Sea, Mediterranean INTRODUCTION (43º55’N and 15º13’E) by a fishhook at a depth of 3.5 m. All lengths of the specimen were In fisheries science, theoretical parameters measured up to the nearest 0.1 cm and weighed such as maximum length, weight and age are with an electric balance to the nearest 0.1 g. The very important as they directly and indirectly sagittal otolith was removed by opening the otic enter into most of the models used in stock bulla under the operculum, washed in freshwa- assessments (BORGES, 2001). Thereupon, updat- ter and stored in plastic tube prior to ageing. ing the maximum size of a species that might The fish was dissected for determination of become commercially exploited is significant. -

CHECKLIST and BIOGEOGRAPHY of FISHES from GUADALUPE ISLAND, WESTERN MEXICO Héctor Reyes-Bonilla, Arturo Ayala-Bocos, Luis E

ReyeS-BONIllA eT Al: CheCklIST AND BIOgeOgRAphy Of fISheS fROm gUADAlUpe ISlAND CalCOfI Rep., Vol. 51, 2010 CHECKLIST AND BIOGEOGRAPHY OF FISHES FROM GUADALUPE ISLAND, WESTERN MEXICO Héctor REyES-BONILLA, Arturo AyALA-BOCOS, LUIS E. Calderon-AGUILERA SAúL GONzáLEz-Romero, ISRAEL SáNCHEz-ALCántara Centro de Investigación Científica y de Educación Superior de Ensenada AND MARIANA Walther MENDOzA Carretera Tijuana - Ensenada # 3918, zona Playitas, C.P. 22860 Universidad Autónoma de Baja California Sur Ensenada, B.C., México Departamento de Biología Marina Tel: +52 646 1750500, ext. 25257; Fax: +52 646 Apartado postal 19-B, CP 23080 [email protected] La Paz, B.C.S., México. Tel: (612) 123-8800, ext. 4160; Fax: (612) 123-8819 NADIA C. Olivares-BAñUELOS [email protected] Reserva de la Biosfera Isla Guadalupe Comisión Nacional de áreas Naturales Protegidas yULIANA R. BEDOLLA-GUzMáN AND Avenida del Puerto 375, local 30 Arturo RAMíREz-VALDEz Fraccionamiento Playas de Ensenada, C.P. 22880 Universidad Autónoma de Baja California Ensenada, B.C., México Facultad de Ciencias Marinas, Instituto de Investigaciones Oceanológicas Universidad Autónoma de Baja California, Carr. Tijuana-Ensenada km. 107, Apartado postal 453, C.P. 22890 Ensenada, B.C., México ABSTRACT recognized the biological and ecological significance of Guadalupe Island, off Baja California, México, is Guadalupe Island, and declared it a Biosphere Reserve an important fishing area which also harbors high (SEMARNAT 2005). marine biodiversity. Based on field data, literature Guadalupe Island is isolated, far away from the main- reviews, and scientific collection records, we pres- land and has limited logistic facilities to conduct scien- ent a comprehensive checklist of the local fish fauna, tific studies. -

Abstract Book

January 21-25, 2013 Alaska Marine Science Symposium hotel captain cook & Dena’ina center • anchorage, alaska Bill Rome Glenn Aronmits Hansen Kira Ross McElwee ShowcaSing ocean reSearch in the arctic ocean, Bering Sea, and gulf of alaSka alaskamarinescience.org Glenn Aronmits Index This Index follows the chronological order of the 2013 AMSS Keynote and Plenary speakers Poster presentations follow and are in first author alphabetical order according to subtopic, within their LME category Editor: Janet Duffy-Anderson Organization: Crystal Benson-Carlough Abstract Review Committee: Carrie Eischens (Chair), George Hart, Scott Pegau, Danielle Dickson, Janet Duffy-Anderson, Thomas Van Pelt, Francis Wiese, Warren Horowitz, Marilyn Sigman, Darcy Dugan, Cynthia Suchman, Molly McCammon, Rosa Meehan, Robin Dublin, Heather McCarty Cover Design: Eric Cline Produced by: NOAA Alaska Fisheries Science Center / North Pacific Research Board Printed by: NOAA Alaska Fisheries Science Center, Seattle, Washington www.alaskamarinescience.org i ii Welcome and Keynotes Monday January 21 Keynotes Cynthia Opening Remarks & Welcome 1:30 – 2:30 Suchman 2:30 – 3:00 Jeremy Mathis Preparing for the Challenges of Ocean Acidification In Alaska 30 Testing the Invasion Process: Survival, Dispersal, Genetic Jessica Miller Characterization, and Attenuation of Marine Biota on the 2011 31 3:00 – 3:30 Japanese Tsunami Marine Debris Field 3:30 – 4:00 Edward Farley Chinook Salmon and the Marine Environment 32 4:00 – 4:30 Judith Connor Technologies for Ocean Studies 33 EVENING POSTER -

Dedication Donald Perrin De Sylva

Dedication The Proceedings of the First International Symposium on Mangroves as Fish Habitat are dedicated to the memory of University of Miami Professors Samuel C. Snedaker and Donald Perrin de Sylva. Samuel C. Snedaker Donald Perrin de Sylva (1938–2005) (1929–2004) Professor Samuel Curry Snedaker Our longtime collaborator and dear passed away on March 21, 2005 in friend, University of Miami Professor Yakima, Washington, after an eminent Donald P. de Sylva, passed away in career on the faculty of the University Brooksville, Florida on January 28, of Florida and the University of Miami. 2004. Over the course of his diverse A world authority on mangrove eco- and productive career, he worked systems, he authored numerous books closely with mangrove expert and and publications on topics as diverse colleague Professor Samuel Snedaker as tropical ecology, global climate on relationships between mangrove change, and wetlands and fish communities. Don pollutants made major scientific contributions in marine to this area of research close to home organisms in south and sedi- Florida ments. One and as far of his most afield as enduring Southeast contributions Asia. He to marine sci- was the ences was the world’s publication leading authority on one of the most in 1974 of ecologically important inhabitants of “The ecology coastal mangrove habitats—the great of mangroves” (coauthored with Ariel barracuda. His 1963 book Systematics Lugo), a paper that set the high stan- and Life History of the Great Barracuda dard by which contemporary mangrove continues to be an essential reference ecology continues to be measured. for those interested in the taxonomy, Sam’s studies laid the scientific bases biology, and ecology of this species. -

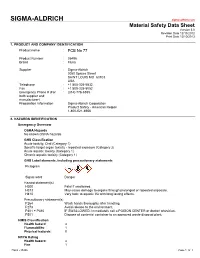

SIGMA-ALDRICH Sigma-Aldrich.Com Material Safety Data Sheet Version 5.0 Revision Date 12/13/2012 Print Date 12/10/2013

SIGMA-ALDRICH sigma-aldrich.com Material Safety Data Sheet Version 5.0 Revision Date 12/13/2012 Print Date 12/10/2013 1. PRODUCT AND COMPANY IDENTIFICATION Product name : PCB No 77 Product Number : 35496 Brand : Fluka Supplier : Sigma-Aldrich 3050 Spruce Street SAINT LOUIS MO 63103 USA Telephone : +1 800-325-5832 Fax : +1 800-325-5052 Emergency Phone # (For : (314) 776-6555 both supplier and manufacturer) Preparation Information : Sigma-Aldrich Corporation Product Safety - Americas Region 1-800-521-8956 2. HAZARDS IDENTIFICATION Emergency Overview OSHA Hazards No known OSHA hazards GHS Classification Acute toxicity, Oral (Category 1) Specific target organ toxicity - repeated exposure (Category 2) Acute aquatic toxicity (Category 1) Chronic aquatic toxicity (Category 1) GHS Label elements, including precautionary statements Pictogram Signal word Danger Hazard statement(s) H300 Fatal if swallowed. H373 May cause damage to organs through prolonged or repeated exposure. H410 Very toxic to aquatic life with long lasting effects. Precautionary statement(s) P264 Wash hands thoroughly after handling. P273 Avoid release to the environment. P301 + P310 IF SWALLOWED: Immediately call a POISON CENTER or doctor/ physician. P501 Dispose of contents/ container to an approved waste disposal plant. HMIS Classification Health hazard: 4 Flammability: 1 Physical hazards: 0 NFPA Rating Health hazard: 4 Fire: 1 Fluka - 35496 Page 1 of 7 Reactivity Hazard: 0 Potential Health Effects Inhalation May be harmful if inhaled. May cause respiratory tract irritation. Skin May be harmful if absorbed through skin. May cause skin irritation. Eyes May cause eye irritation. Ingestion May be fatal if swallowed. 3. COMPOSITION/INFORMATION ON INGREDIENTS Synonyms : 3,3′,4,4′-PCB 3,3′,4,4′-Tetrachlorobiphenyl Formula : C12H6Cl4 Molecular Weight : 291.99 g/mol No ingredients are hazardous according to OHSA criteria. -

Universidad Nacional Agraria La Molina

UNIVERSIDAD NACIONAL AGRARIA LA MOLINA ESCUELA DE POSTGRADO MAESTRÍA EN ESTADÍSTICA APLICADA “Relaciones ontogénicas y espacio-temporales en la dieta del calamar gigante (Dosidicus gigas) en Perú, utilizando un Modelo Aditivo Generalizado”. Presentada por: ANA RENZA PAOLA ALEGRE NORZA TESIS PARA OPTAR EL GRADO DE MAGISTER SCIENTIAE EN: ESTADÍSTICA APLICADA Lima - Perú 2011 UNIVERSIDAD NACIONAL AGRARIA LA MOLINA ESCUELA DE POSTGRADO MAESTRÍA EN ESTADÍSTICA APLICADA “Relaciones ontogénicas y espacio-temporales en la dieta del calamar gigante (Dosidicus gigas) en Perú, utilizando un Modelo Aditivo Generalizado”. Presentada por: ANA RENZA PAOLA ALEGRE NORZA TESIS PARA OPTAR EL GRADO DE MAGISTER SCIENTIAE EN: ESTADÍSTICA APLICADA Sustentada y aprobada por el siguiente jurado: Mg. Rino Sotomayor Ruiz Mg. César Menacho Chiok PRESIDENTE MIEMBRO Mg. Clodomiro Miranda Villagómez Mg. Víctor Maehara Oyata MIEMBRO PATROCINADOR Dedicado a mis padres Mario┼ y Angélica┼ que son mi fuente de inspiración y a mis hijos Paula y Salvador quienes son el motor que me impulsa a cumplir mis sueños. AGRADECIMIENTOS En primer lugar quiero agradecer a mi profesor M Sc. Víctor Maehara, mi mentor, patrocinador y maestro, por ayudarme minuciosamente con el desarrollo de esta tesis, siendo siempre muy acucioso en sus críticas; pero también por darme la confianza de estar desarrollando un buen trabajo. También quiero dar las gracias al Dr. Arnaud Bertrand (IRD - Francia) por haberme dado la oportunidad de estudiar esta maestría, por su incansable apoyo y sabios consejos, por darme el ánimo para seguir en el camino y no desfallecer, por ser amigo y compañero en esta lucha, sin su voto de confianza no hubiera podido subir este peldaño en mi carrera. -

Feeding Habits of Centropomus Undecimalis (Actinopterygii, Centropomidae) in the Parnaíba River Delta, Piauí, Brazil

Brazilian Journal of Development 39536 ISSN: 2525-8761 Feeding habits of Centropomus undecimalis (Actinopterygii, Centropomidae) in the Parnaíba river delta, Piauí, Brazil Alimentação do Centropomus undecimalis (Actinopterygii, Centropomidae) no estuário do delta do rio Parnaíba, Piauí, Brasil DOI:10.34117/bjdv7n4-423 Recebimento dos originais: 07/03/2021 Aceitação para publicação: 16/04/2021 José Rafael Soares Fonseca Doutorando em Recursos Pesqueiros e Engenharia de Pesca Programa de Pós-Graduação em Recursos Pesqueiros e Engenharia de Pesca, Centro de Engenharias e Ciências Exatas, Universidade Estadual do Oeste do Paraná – UNIOESTE, Rua da Faculdade, 645, 85903-000 – Toledo– PR – Brasil E-mail: [email protected] Cezar Augusto Freire Fernandes Doutorado em Recursos Pesqueiros e Aquicultura Universidade Federal do Delta do Parnaíba – UFDPAR, Av. São Sebastião, 2819 Bairro Nossa Senhora de Fátima– CEP: 64.202-020 – Parnaíba – PI – Brasil E-mail: [email protected] Francisca Edna de Andrade Cunha Doutorado em Ciências Biológicas Universidade Federal do Delta do Parnaíba – UFDPAR, Av. São Sebastião, 2819 Bairro Nossa Senhora de Fátima– CEP: 64.202-020 – Parnaíba – PI – Brasil E-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT The objective of this work was to evaluate the feeding of Centropomus undecimalis in the estuary of the Parnaíba river delta, with emphasis on diet composition during seasonal variations between dry and rainy seasons. The samples were obtained from artisanal fishing with gillnets, from June 2014 - July 2015. The individuals were measured, weighed and dissected to remove the stomachs. The fish diet was analyzed using the methods: Gravimetric, Frequency of Occurrence, Dominance of the item and Food Index. -

Updated Checklist of Marine Fishes (Chordata: Craniata) from Portugal and the Proposed Extension of the Portuguese Continental Shelf

European Journal of Taxonomy 73: 1-73 ISSN 2118-9773 http://dx.doi.org/10.5852/ejt.2014.73 www.europeanjournaloftaxonomy.eu 2014 · Carneiro M. et al. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License. Monograph urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:9A5F217D-8E7B-448A-9CAB-2CCC9CC6F857 Updated checklist of marine fishes (Chordata: Craniata) from Portugal and the proposed extension of the Portuguese continental shelf Miguel CARNEIRO1,5, Rogélia MARTINS2,6, Monica LANDI*,3,7 & Filipe O. COSTA4,8 1,2 DIV-RP (Modelling and Management Fishery Resources Division), Instituto Português do Mar e da Atmosfera, Av. Brasilia 1449-006 Lisboa, Portugal. E-mail: [email protected], [email protected] 3,4 CBMA (Centre of Molecular and Environmental Biology), Department of Biology, University of Minho, Campus de Gualtar, 4710-057 Braga, Portugal. E-mail: [email protected], [email protected] * corresponding author: [email protected] 5 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:90A98A50-327E-4648-9DCE-75709C7A2472 6 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:1EB6DE00-9E91-407C-B7C4-34F31F29FD88 7 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:6D3AC760-77F2-4CFA-B5C7-665CB07F4CEB 8 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:48E53CF3-71C8-403C-BECD-10B20B3C15B4 Abstract. The study of the Portuguese marine ichthyofauna has a long historical tradition, rooted back in the 18th Century. Here we present an annotated checklist of the marine fishes from Portuguese waters, including the area encompassed by the proposed extension of the Portuguese continental shelf and the Economic Exclusive Zone (EEZ). The list is based on historical literature records and taxon occurrence data obtained from natural history collections, together with new revisions and occurrences. -

Order MYCTOPHIFORMES NEOSCOPELIDAE Horizontal Rows

click for previous page 942 Bony Fishes Order MYCTOPHIFORMES NEOSCOPELIDAE Neoscopelids By K.E. Hartel, Harvard University, Massachusetts, USA and J.E. Craddock, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, Massachusetts, USA iagnostic characters: Small fishes, usually 15 to 30 cm as adults. Body elongate with no photophores D(Scopelengys) or with 3 rows of large photophores when viewed from below (Neoscopelus).Eyes variable, small to large. Mouth large, extending to or beyond vertical from posterior margin of eye; tongue with photophores around margin in Neoscopelus. Gill rakers 9 to 16. Dorsal fin single, its origin above or slightly in front of pelvic fin, well in front of anal fins; 11 to 13 soft rays. Dorsal adipose fin over end of anal fin. Anal-fin origin well behind dorsal-fin base, anal fin with 10 to 14 soft rays. Pectoral fins long, reaching to about anus, anal fin with 15 to 19 rays.Pelvic fins large, usually reaching to anus.Scales large, cycloid, and de- ciduous. Colour: reddish silvery in Neoscopelus; blackish in Scopelengys. dorsal adipose fin anal-fin origin well behind dorsal-fin base Habitat, biology, and fisheries: Large adults of Neoscopelus usually benthopelagic below 1 000 m, but subadults mostly in midwater between 500 and 1 000 m in tropical and subtropical areas. Scopelengys meso- to bathypelagic. No known fisheries. Remarks: Three genera and 5 species with Solivomer not known from the Atlantic. All Atlantic species probably circumglobal . Similar families in occurring in area Myctophidae: photophores arranged in groups not in straight horizontal rows (except Taaningichthys paurolychnus which lacks photophores). Anal-fin origin under posterior dorsal-fin anal-fin base. -

BODRUM PAMUKKALE Mark O’Connell Photography 26 102 Istock FETHIYE KAPADOKYA 44 110

TURKEY I MONTENEGRO I GREECE I MIAMI Charter & Brokerage & Charter Yacht Services & Bunkering & Services Yacht Concierge Itinerary Planning Agency Special Events Provisioning www.c2cyacthing.com EXPERIENCE Agency I Concierge I Yacht Services & Bunkering I Provisioning I Itinerary Planning I Special Events I Brokerage I Charter COAST TO COAST SEA TO SEA We enjoy discovering the best places on the most reliable coasts, offering you the best local places, the best entertainment places, the great flavors. Turkey’s most experienced marine service we provide to you for many years. We love the sea and our work. EDITOR CLIFFORD H. POLLEY President & CEO C2C Yachting International Welcome to our latest edition, highlighting We are driven by our mantra to explore not the array of destinations we cover to only what you are going to do, but what you’re spotlighting ideal cruising and vacation not going to do. Allow us to show you. locales. As we navigate the perplexity of life, seize the opportunity to unplug in the serenity From all of us at C2C Yachting we wish you of paradise. every success with your adventures, wherever they may take you. C2C Yachting’s coverage has expanded from Turkey, Greece, Montenegro and Croatia To keep abreast of key information to include our main US office in Miami, please continue to visit our website Florida. Taking our services global allows www.c2cyachting.com us to enhance your experience and the pages which follow exhibit our first-rate capabilities. Sincerely, C2C Yachting takes pride in our commitment to provide the highest level of service inclusive of operational needs, cruising itineraries, dining and nightlife curated to your wishes, all fulfilled by the highest level of professional staff.