Implementing Preventive Architectural Conservation: Do Historic Property

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ansteorran Internal Letter of Intent 2009-06

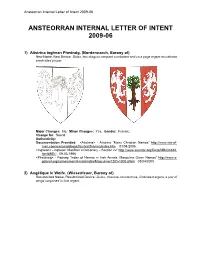

Ansteorran Internal Letter of Intent 2009-06 ANSTEORRAN INTERNAL LETTER OF INTENT 2009-06 1) Alistrina inghean Phedraig. (Bordermarch, Barony of) New Name. New Device. Gules, two dragons rampant combatant and on a page argent an oak tree eradicated proper. Major Changes: No. Minor Changes: Yes. Gender: Female. Change for: Sound. Authenticity: Documentation Provided: <Alistrina> - Alistrina “Manx Christian Names” http://www.isle-of- man.com/manxnotebook/famhist/fnames/index.htm 03/04/2005. <inghean> - inghean “MacBain‟s Dictionary – Section 22” http://www.ceantar.org/Dicts/MB2/mb22. html#MB.I 09-03-1996 <Pha‟draig> - Padraig “Index of Names in Irish Annals: Masculine Given Names” http://www.s- gabriel.org/names/mari/AnnalsIndex/Masculine/1201-1300.shtml 03/04/2005 2) Angélique le Wolfe. (Wiesenfeuer, Barony of) Resubmitted Name. Resubmitted Device. Gules, chaussé countermine, fimbriated argent, a pair of wings conjoined in lure argent. Ansteorran Internal Letter of Intent 2009-06 Submission History: [Name] Angéle le Wolfe was returned 06/08 for insufficient documentation of <Angele> in period. Submission History: [Device] Ermine sable with tails argent, on a pile gules, wings argent was returned for lack of a name 06/08. Additionally, this needs a complete redraw: whether this is meant to be a chaussé field division or an incorrectly drawn pile, the contrast is poor and cause for return; the ermine spots look odd and are too many and too small; and the wings need to be drawn better as well. Please see the commentary for details! [Asterisk Note: I recolored the red because it did not scan well.] Major Changes: No. -

The Palace of Pleasure; Elizabethan Versions of Italian and French

THE alace of IHleasure ELIZABETHAN VERSIONS OF ITALIAN AND FRENCH NOVELS FROM BOCCACCIO, BANDELLO, CINTHIO, STRAPAROLA, QUEEN MARGARET OF NAVARRE, AND OTHERS DONE INTO ENGLISH BY WILLIAM PAINTER NOW AGAIN EDITED FOR THE FOURTH TIME BY JOSEPH JACOBS VOL. HI. LONDON: PUBLISHED BY DAVID NUTT IN THE STRAND a, MDCCCXC TABLE OF CONTENTS. VOLUME III. TOME II.— Continued. TITLE PAGE (EDITION 1 580) CJe 53alace of Peasure^ THE TWENTY-THIRD NOUELL. The infortunate manage of a Gentleman, called Antonio Bologna, wyth the Duchejfe of Malfi, and the pitifull death of them loth. The great Honor and authority men haue in thys World, and the greater their eftimation is, the more fenfible and notorious are the faultes by theim committed, and the greater is their flaunder. In lyke manner more difficult it is for that man to tolerate and fus- tayne Fortune, which al the dayes of his life hath lyued at his eafe, if by chaunce he fall into any great neceffity than for hym whych neuer felt but woe, mifliap, and aduerfity. Dyonifius the Tyraunt of Scicilia, felt greater payne when hee was expelled his Kyng- dome, than Milo did, beinge banifhed from Rome: for fo mutch as the one was a Soueraygne Lorde, the fonne of a Kynge, a lufticiary on Earth, and the other but a fimple Citizen of a Citty, wherein the People had Lawes, and the Lawes of Magis- trates were had in reuerence. So lykewyfe the fall of a high and lofty Tree, maketh greater noyfe, than that whych is low and little. Hygh Towers, and ftately Palaces of Prynces bee feene further of, than the poore Cabans, and homely Sheepe- heardes Sheepecotes : the Walles of lofty Cittyes more a loofe doe Salute the Viewers of the fame, than the fimple Caues, which the Poore doe digge belowe theMountayneRockes. -

UC San Diego UC San Diego Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC San Diego UC San Diego Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Adaptive Design & Optimization of 3D Printable, Shape-Changing, Ballistically Deployable Drone Platforms Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/8905d3kh Author Henderson, Luke Warby Publication Date 2017 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO Adaptive Design & Optimization of 3D Printable, Shape-Changing, Ballistically Deployable Drone Platforms A thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Master of Science in Structural Engineering by Luke Henderson Committee in charge: Professor Falko Kuester, Chair Professor Thomas Bewley Professor John B. Kosmatka 2017 Copyright Luke Henderson, 2017 All rights reserved. The thesis of Luke Henderson is approved, and it is accept- able in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: Chair University of California, San Diego 2017 iii EPIGRAPH Design is not just what it looks like and feels like. Design is how it works. —Steve Jobs iv TABLE OF CONTENTS Signature Page . iii Epigraph . iv Table of Contents . v List of Figures . vii Acknowledgements . viii Vita ......................................... ix Abstract of the Thesis . x Chapter 1 Introduction . 1 Chapter 2 Concept Development . 4 2.1 Related Work . 4 2.1.1 Unmanned Aerial Vehicles . 4 2.1.2 Biomimicry . 6 2.1.3 Optimization . 6 2.1.4 multi-disciplinary optimization . 9 2.2 Possible Application Scenarios . 10 2.2.1 Adaptive Design and 3D printing . 11 2.2.2 Ground Launched Air Deployed . 13 2.2.3 High Altitude Low Opening . 14 2.2.4 Folding platform / small footprint . -

Name, a Novel

NAME, A NOVEL toadex hobogrammathon /ubu editions 2004 Name, A Novel Toadex Hobogrammathon Cover Ilustration: “Psycles”, Excerpts from The Bikeriders, Danny Lyon' book about the Chicago Outlaws motorcycle club. Printed in Aspen 4: The McLuhan Issue. Thefull text can be accessed in UbuWeb’s Aspen archive: ubu.com/aspen. /ubueditions ubu.com Series Editor: Brian Kim Stefans ©2004 /ubueditions NAME, A NOVEL toadex hobogrammathon /ubueditions 2004 name, a novel toadex hobogrammathon ade Foreskin stepped off the plank. The smell of turbid waters struck him, as though fro afar, and he thought of Spain, medallions, and cork. How long had it been, sussing reader, since J he had been in Spain with all those corkoid Spanish medallions, granted him by Generalissimo Hieronimo Susstro? Thirty, thirty-three years? Or maybe eighty-seven? Anyhow, as he slipped a whip clap down, he thought he might greet REVERSE BLOOD NUT 1, if only he could clear a wasp. And the plank was homely. After greeting a flock of fried antlers at the shevroad tuesday plied canticle massacre with a flash of blessed venom, he had been inter- viewed, but briefly, by the skinny wench of a woman. But now he was in Rio, fresh of a plank and trying to catch some asscheeks before heading on to Remorse. I first came in the twilight of the Soviet. Swigging some muck, and lampreys, like a bad dram in a Soviet plezhvadya dish, licking an anagram off my hands so the ——— woundn’t foust a stiff trinket up me. So that the Soviets would find out. -

Barony of Al-Barran Roll of Arms 2012

al-Barran Roll of Arms 2012 Barony of al-Barran Roll of Arms 2012 al-Barran Roll of Arms 2012 Adam Steadfast Adelicia von Hohenschwangau Per chevron azure and Per chevron vert and Or, sable, a phoenix Or rising two voided hearts Or and from flames proper issu- a swan naiant sable ant from the line of divi- sion and a rose argent Aelflaed of Duckford Aelinel von Nachtenwald Vert, a duck rampant Quarterly azure and argent, billed and counter-ermine, on a membered Or, above Latin saltire throughout a ford proper and on argent a crescent fess- an escutcheon azure, wise gules in pale a sun and a key fesswise within a bordure Or Ælric Kyrri Aidan Cocrinn Azure, a cross arron- Vert, three chevronels di between four braced inverted Or roundels, a bordure argent al-Barran Roll of Arms 2012 Aigiarn Aljin Aindrea Mac Parthaláin Gules, three crescents in Azure, an equal-armed pall inverted horns to Celtic cross formy Or center argent between issuant from a mount three mullets of six vert points Or A'isha al-Naysaburiya Alaric der Jaeger Or, a sexfoil within the Arabic words "kaana khafi Per pale azure and bishshawkihi ja- argent, on a trian- maalat-il-wardata" gle inverted an in orle gules. ankh, a bordure embattled, all counterchanged Alaric the Fool Alasdair MacArthur Per fess argent and Or, a saltire vert sable, a fool's hat per pale gules and vert, and a sun Or al-Barran Roll of Arms 2012 Aldred Colson Aleron of Eagle's Reach Quarterly vert and sable, Per saltire azure and a saltire between in pale gules, four bendlets and two crescents argent. -

Ansteorran College of Heralds

ANSTEORRAN COLLEGE OF HERALDS Annotated Collated Commentary on IloI 0008 Unto the Ansteorran College of Heralds does Estrill Swet, Retiarius Pursuivant, make greetings. For information on commentary submission formats or to receive a copy of the collated commentary, you can contact me at: Deborah Sweet 824 E 8th, Stillwater, OK 74074 405/624-9344 (before 10pm) [email protected] Commenters for this issue: Da’ud ibn Auda - al-Jamal Herald Magnus von Lübeck - Raven's Fort. All items were checked against the on-line O&A. If you are preparing items for the ILOI please make sure the submitter’s branch is listed. This is helpful for those of us who travel. Gawain of Miskbridge – Green Anchor Herald, Calontir Elfsea - Timothy of Glastonbury (Forerynel Pursuivant), Sigmund Theodoric von Halberstadt (Western Regional Pursuivant), Willim Penbraus, Rebekah of Newcastle. Note : Commentary is only provided on Armorial entries as the books of the Nautilus library were not available. Collated Commentary on IloI 0008 1) Alistair of Avalon (Stargate) New device. Name registered 10/91. Azure, a bears head cabossed within a mascule of four needles Or. Gawain of Miskbridge [Device] That’s a "mascle". Elfsea [Device] This device cannot reasonably be reproduced from the blazon. The arrangement of the needles as 'head to toe' is unclear. Save this point, no conflicts were found. 1. COLLEGE ACTION: Device: Forwarded to Laurel 2) Brigit Ni Sheachnasaigh (Steppes) New device. Name registered 0/00. Per bend sable and argent, a pair of barnacles counterchanged. Magnus von Lübeck [Device] Name registered February 1995 (via Ansteorra). Elfsea [Device] Cannot find barnacles within the Ordinary. -

ÆTHELMEARC Andreas Jäger Von Holstein

ACCEPTANCES Page 1 of 20 September 2007 LoAR THE FOLLOWING ITEMS HAVE BEEN REGISTERED: ÆTHELMEARC Andreas Jäger von Holstein. Name and device. Argent, a bear sejant erect sable and on a chief enarched rayonny gules a lightning bolt argent. Elyenora Houll. Device. Argent, three leaves bendwise sinister vert between two scarpes sable between six dragonflies purpure. This was originally pended on the February 2007 LoAR. Marija Kotok. Name change from Mariia Kotova. Precedent set in October 2002 forbade the registration of unmarked patronymics in Russian names: Bola is a Russian masculine given name. Lacking evidence that Russian used unmarked patronymic bynames, we have changed this to the patronymic form Bolin in order to register this name. [Gorm Bolin, 10/2002, A-Middle] This appeal raised the issue of whether there is evidence for unmarked patronymic bynames in Russian. The submitter and commenters provided examples that could be interpreted as unmarked patronymics in Russian names. Furthermore, they found statements from authorities on Russian names supporting unmarked patronymics as a rare practice in Russian names. The evidence presented is sufficient to allow unmarked patronymics in Russian names as a rare, but registerable practice. Therefore, this name is registerable. For more details on the information provided for this practice, see this month’s Cover Letter. This was originally pended on the February 2007 LoAR. Her old name, Mariia Kotova, is released. Petr Kotok. Name change from Petr Kotov. His old name, Petr Kotov, is released. This name is a Russian name using an unmarked patronymic. For more information on the registerability of this practice, see this month’s Cover Letter. -

ACCEPTANCES Page 1 of 45 September 2002 Loar

Page 1 of 45 September 2002 LoAR ACCEPTANCES ÆTHELMEARC Ailith of H eronter. Device reblazon. Per bend azure and vert, a bend b etween a cro ss crosslet and a sprig bend wise argent. The previous blazo n, Per bend azure and vert, a bend between a cross crosslet and a sprig argent, did not correctly specify the orientation of the sprig. AN TIR Alexander of M aldon. Name and device. Quarterly gules and sable, a Bowen knot crosswise between four lozenges Or. Andreu Recheles. Device. P er fess Or and gules, a winged rat couchant and a wagon wheel counterchanged. Winged quadrupeds have their wings addorsed by default, so this detail need not be specified in the blazon. Aquaterra, Barony of. Badge (see RETURNS for order name O rder of the Starfish). Azure, an estoile within a bordure nebuly Or. Please advise the submitters to draw the estoile larger and the bordure somewhat narrower. Arnóra in hárfagra. Name. Submitted as Arnóra inn hárfagri, the submitted byname is a m asculine form. Since the given name is feminine, we have changed the byname to the feminine form in hárfagra in order to register this name. Bagsecg of Aquaterra. Holding name and device (see RETURNS for name). Purpure, in pale an eagle argent and a crossbow fesswise Or. Submitted under the name Basecg von Basel. Caterina Giulia di Raffaello Strozzi. Alternate name Ælfflæd Ælfgaresdo htor. Consta ncia Tattersall. Device change. Argent goutty, on a chamfron azure a cross patonce argent. Please advise the submitter to draw a more standard chamfron. Chamfrons in heraldry generally have a more distinct "scoop" where the eyes are. -

The Anstaorran Gazette

The Ansteorran Gazette © 2000 Society for Creative Anachronism, Inc. Ridgway’s Publishing House FEBRUARY, A.S. XXXIV (2000 A.D.) 1 DOLLAR A LETTER FROM THE ZODIACUS HERALD ANSTEORRAN Greetings! I am HL Rosalia O Brogan the somewhat new Zodiacus Herald. COLLEGE OF HERALDS I will be endeavoring during my term in this office to improve the Order of Prece- CALENDAR dence (OP) and make it more accessible to the populace of the Kingdom. A reminder to EVERY MONTH that end, court reports are due within two weeks of an event. These should be sent to 15 Deadline for submissions Zodiacus (myself), Forerynel Pursuivant, Sable Scroll, and to Star Signet. It is very due at ASTERISK. important that all these offices receive copies of this report as quickly as possible so that the OP may be as accurate as possible at all times. Please do not hand me court reports 20 Comments on ILoI of pre- at the event where it was taken, as this report must go to several offices I will only accept vious month due to RETIARIUS. these reports by mail. Items for Ansteorran Ga- If you have corrections that need to be made to the OP please send me a photocopy zette due to OBELISK. of the charter award scroll. If the charter is missing or was not given I will need the name of the individual, award given, the event the award was given at, and what crown 15-19 MARCH -- GULF WARS gave the award. For name corrections a letter from the individual, whose name is to be Gulf Wars -- CoH meeting corrected is preferable. -

Handbuch Der Theoretischen Und Praktischen Heraldik Unter Steter Bezugnahme Auf Die Übrigen Historischen Hilfswissenschaften

Handbuch der theoretischen und praktischen Heraldik unter steter Bezugnahme auf die übrigen historischen Hilfswissenschaften. Vorangestellte Bemerkung. Der vorliegende Text ist eine Bearbeitung der beiden Teile des Heraldikhandbuches von Otto Titan von Hefner, aus den Jahren 1861 (Theoretische Heraldik) und 1863 (Praktische Heraldik). Es wurde die Schreibweise heutigen Gepflogenheiten (Heirat statt Heurath, Tor statt Thor etc. ) angepasst um den Text leichter lesbar zu machen. Es fehlen die Abbildungen, die Seitenzahlen stimmen natürlich nicht und wurden bei Verweisen auch nicht angepasst. Auf meinem Webauftritt sind die beiden Teile zu konsultieren, dort werde ich auch Fehler korrigieren und Links bereithalten. Es sei nach darauf hingewiesen, dass die ursprüngliche Digitalisierung von Google Books durchgeführt wurde. Google Books sei daher mein Dank und meine Anerkennung ausgedrückt. Der unbearbeitete Text, dann aber auch mit vielen OCRisierungsfehlern, kann unter der nachstehenden Adresse eingesehen werden: http://books.google.de/books/reader?id=IYRTAAAAcAAJ&hl=de&printsec=frontcover&outp ut=reader&pg=GBS.PA19 Inhaltsverzeichnis Handbuch der theoretischen und praktischen Heraldik unter steter Bezugnahme auf die übrigen historischen Hilfswissenschaften. ................................................................................. 1 Vorangestellte Bemerkung. ........................................................................................................ 1 Erster Teil Theoretische Heraldik .............................................................................................. -

Design Your Personal Coat of Arms: Rubric Elements

Design your personal coat of arms: Select a shape for your shield. You will put your "motto for life" at the bottom or the top of the shield. Here are some examples, but you will find more on page 3 of this document: 1. Divide the shield into three or four parts. In each part you will symbolically depict one of the following: 1. Your greatest success 2. What you value most 3. Your highest goal in life 4. Your goal for humankind 5. Your family’s importance/Your position in your family 6. Something else (that is important to you) of your choosing 2. Use a piece of construction paper to display your coat of arms. Neatness, presentation, and creativity count. 3. Attach a one–paragraph explanation for each of the three or four sections symbolically depicted on the shield, and explain in one additional paragraph why you chose your "motto for life." These four/five paragraphs must be typed and edited. USE YOUR IMAGINATION AND HAVE FUN! Rubric Elements Your Coat of Arms includes: • includes your "motto for life" and images that symbolically depict your greatest successes, goals, etc. (25 points) • shows neatness, presentation (10 points) • shows creativity (25 points) • contains powerful explanations for each of the elements (25 points) • contains clarity and correctness of language (15 points) 1 Choosing the charges on your shield: A charge is what is shown on the base color of your shield. Animals were frequently used as a main charge. Animals were shown in certain traditional postures, which were not meant to be realistic pictures of the animals. -

Roll of Arms

Roll of Arms Kingdom of the Outlands For Their Royal Majesties Artan VI and Aziza April A.S. XXXXI Presented by the combined efforts of Duchess Kathryn of Iveragh, Ardent Herald, and Arglwydd Llywus ap Alan, Wharrow Herald (Roll contains arms through December 2006 LOAR) Roll of Arms -- Kingdom of the Outlands -- April 1, A.S. XXXXI Adam Stedefast Aindrea Mac Pharláin Per chevron azure and Azure, an equal-armed sable, a phoenix Or rising Celtic cross formy Or issuant from flames proper issuant from a mount vert (0103) from the line of division and a rose argent (0402) Aelflaed of Duckford A'isha bint Asad Ud-Din Vert, a duck rampant argent, Or, a sexfoil within the billed and membered Or, Arabic words "kaana khafi above a ford proper and on bishshawkihi jamaalat-il- an escutcheon azure, in pale wardata" in orle gules (0111) a sun and a key fesswise (name change in process to within a bordure Or (8411) A'isha bint al-Miraayaat 0612) Ælric Kyrri Alaric der Jaeger Azure, a cross arrondi Per pale azure and argent, between four roundels, a on a triangle inverted an bordure argent (9802) ankh, a bordure embattled, all counterchanged (9802) Aidan Cocrinn Alaric the Fool Vert, three chevronels Per fess argent and sable, a braced inverted Or (8604) fool's hat per pale gules and vert, and a sun Or (9504) Aigiarn Aljin Alasdair MacArthur Gules, three crescents in Or, a saltire vert (0203) pall inverted horns to center argent between three mullets of six points Or (0312) Sunday, April 01, 2007 Page 1 of 20 Alethea la Sage Anna Fae Per bend sinister