Heraldic Symbolism and Convention

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Heraldic Terms

HERALDIC TERMS The following terms, and their definitions, are used in heraldry. Some terms and practices were used in period real-world heraldry only. Some terms and practices are used in modern real-world heraldry only. Other terms and practices are used in SCA heraldry only. Most are used in both real-world and SCA heraldry. All are presented here as an aid to heraldic research and education. A LA CUISSE, A LA QUISE - at the thigh ABAISED, ABAISSÉ, ABASED - a charge or element depicted lower than its normal position ABATEMENTS - marks of disgrace placed on the shield of an offender of the law. There are extreme few records of such being employed, and then only noted in rolls. (As who would display their device if it had an abatement on it?) ABISME - a minor charge in the center of the shield drawn smaller than usual ABOUTÉ - end to end ABOVE - an ambiguous term which should be avoided in blazon. Generally, two charges one of which is above the other on the field can be blazoned better as "in pale an X and a Y" or "an A and in chief a B". See atop, ensigned. ABYSS - a minor charge in the center of the shield drawn smaller than usual ACCOLLÉ - (1) two shields side-by-side, sometimes united by their bottom tips overlapping or being connected to each other by their sides; (2) an animal with a crown, collar or other item around its neck; (3) keys, weapons or other implements placed saltirewise behind the shield in a heraldic display. -

Flags and Banners

Flags and Banners A Wikipedia Compilation by Michael A. Linton Contents 1 Flag 1 1.1 History ................................................. 2 1.2 National flags ............................................. 4 1.2.1 Civil flags ........................................... 8 1.2.2 War flags ........................................... 8 1.2.3 International flags ....................................... 8 1.3 At sea ................................................. 8 1.4 Shapes and designs .......................................... 9 1.4.1 Vertical flags ......................................... 12 1.5 Religious flags ............................................. 13 1.6 Linguistic flags ............................................. 13 1.7 In sports ................................................ 16 1.8 Diplomatic flags ............................................ 18 1.9 In politics ............................................... 18 1.10 Vehicle flags .............................................. 18 1.11 Swimming flags ............................................ 19 1.12 Railway flags .............................................. 20 1.13 Flagpoles ............................................... 21 1.13.1 Record heights ........................................ 21 1.13.2 Design ............................................. 21 1.14 Hoisting the flag ............................................ 21 1.15 Flags and communication ....................................... 21 1.16 Flapping ................................................ 23 1.17 See also ............................................... -

Bibliomara: an Annotated Indexed Bibliography of Cultural and Maritime Heritage Studies of the Coastal Zone in Ireland

BiblioMara: An annotated indexed bibliography of cultural and maritime heritage studies of the coastal zone in Ireland BiblioMara: Leabharliosta d’ábhar scríofa a bhaineann le cúltúr agus oidhreacht mara na hÉireann (Stage I & II, January 2004) Max Kozachenko1, Helen Rea1, Valerie Cummins1, Clíona O’Carroll2, Pádraig Ó Duinnín3, Jo Good2, David Butler1, Darina Tully3, Éamonn Ó Tuama1, Marie-Annick Desplanques2 & Gearóid Ó Crualaoich 2 1 Coastal and Marine Resources Centre, ERI, UCC 2 Department of Béaloideas, UCC 3 Meitheal Mara, Cork University College Cork Department of Béaloideas Abstract BiblioMara: What is it? BiblioMara is an indexed, annotated bibliography of written material relating to Ireland’s coastal and maritime heritage; that is a list of books, articles, theses and reports with a short account of their content. The index provided at the end of the bibliography allows users to search the bibliography using keywords and authors’ names. The majority of the documents referenced were published after the year 1900. What are ‘written materials relating to Ireland’s coastal heritage’? The BiblioMara bibliography contains material that has been written down which relates to the lives of the people on the coast; today and in the past; their history and language; and the way that the sea has affected their way of life and their imagination. The bibliography attempts to list as many materials as possible that deal with the myriad interactions between people and their maritime surroundings. The island of Ireland and aspects of coastal life are covered, from lobster pot making to the uses of seaweed, from the fate of the Spanish Armada to the future of wave energy, from the sailing schooner fleets of Arklow to the County Down herring girls, from Galway hookers to the songs of Tory Islanders. -

Kingdom of Atlantia Scribal Handbook

Kingdom of Atlantia Scribal Handbook TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction to 2016 Revision 4 Scribal Arts Primer Analysing a Style—Kingdom of Lochac 6 Layout and Design of Scrolls—Kingdoms of the Middle & Atlantia 9 Contemporary Techniques for Producing Scrolls and Advice for 11 Choosing Tools and Materials—Kingdom of the Middle Illumination The Ten Commandments to Illuminators—Kingdom of the West 19 Advice on Painting—Kingdom of the Middle 20 Design and Construction of Celtic Knotwork—Kingdom of the West 27 Calligraphy The Ten Commandments to Calligraphers—Kingdom of the West 31 Advice on Calligraphy—Kingdom of the Middle 32 The Sinister Scribe—Kingdom of the Middle 34 How to Form Letter—Kingdom of the Middle 36 Calligraphy Exemplars—Kingdom of the Middle 38 Heraldry and Heraldic Display Interpreting a Blazon 51 Heraldry for Scribes—Kingdom of the West 52 Blazoning of Creatures—Kingdom of Atlantia 66 Achievements in Heraldic Display—Kingdom of Atlantia 73 Some Helms and Shields Used in Heraldic Art—Kingdom of the Middle 83 Atlantian Scroll Conventions Artistic Expectations for Kingdom scrolls 87 Typographical Conventions for scroll texts 87 Kingdom Policy Regarding the College of Scribes 88 Kingdom Law Regarding the College of Scribes 90 How to Receive a Kingdom Scroll Assignment 90 Kingdom Law pertaining to the issuance of scrolls 88 Scroll Text Conventions in the Kingdom of Atlantia 89 Mix and Match Scroll Texts 91 List of SCA Dates 94 List of Atlantian Monarchs 95 Scroll Texts by Type of Award 97 Non-Armigerous Awards Fountain 101 Herring 102 King’s Award of Excellence (KAE) 103 Nonpariel 104 Queen’s Order of Courtesy (QOC) 105 Shark’s Tooth 106 Silver Nautilus 107 Star of the Sea 108 Undine 109 Vexillum Atlantia 110 Order of St. -

ÆTHELMEARC Alays De Rambert. Name and Device. Per Chevron Raguly Gules and Or, Three

ACCEPTANCES Page 1 of 32 March 2010 LoAR THE FOLLOWING ITEMS HAVE BEEN REGISTERED: ÆTHELMEARC Alays de Rambert. Name and device. Per chevron raguly gules and Or, three hares sejant counterchanged. Great 14th C Perigord name! Annys de Valle. Name and device. Per chevron inverted purpure and sable, a chevron inverted ermine, in chief a fox passant argent. Anzelm Wo{l/}czek. Name and device. Or, in pale a woman affronty with arms raised argent vested vert crined sable seated atop a crow sable. Submitted as Anzelm W{o-}u{l/}czek, the documentation provided on the LoI for the byname was for the spelling Wo{l/}czek. No documentation was provided, and none could be found, for the change from o to {o-}u. We have corrected the byname to match the documentation in order to register the name. Aron of Hartstone. Holding name and device (see RETURNS for name). Gules, a fret Or between two wyverns sejant respectant argent. Submitted under the name Galdra-Aron. Avelina del Dolce. Device. Vert, in pale a slipper Or and a unicorn rampant argent. Belcolore da Castiglione. Name and device. Argent, in pale a lion statant gules and a castle purpure. This is clear of the device of Joyesse de Wolfe of Cath Mawr, Argent, a lion sejant erect coward guardant contourny gules seated upon a maintained rock sable and playing a maintained viol vert with a bow sable, reblazoned elsewhere in this letter. There is a CD for the change of posture of the lion and a CD for the addition of the castle. -

Ansteorran Internal Letter of Intent 2009-06

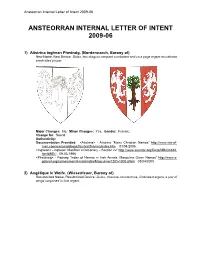

Ansteorran Internal Letter of Intent 2009-06 ANSTEORRAN INTERNAL LETTER OF INTENT 2009-06 1) Alistrina inghean Phedraig. (Bordermarch, Barony of) New Name. New Device. Gules, two dragons rampant combatant and on a page argent an oak tree eradicated proper. Major Changes: No. Minor Changes: Yes. Gender: Female. Change for: Sound. Authenticity: Documentation Provided: <Alistrina> - Alistrina “Manx Christian Names” http://www.isle-of- man.com/manxnotebook/famhist/fnames/index.htm 03/04/2005. <inghean> - inghean “MacBain‟s Dictionary – Section 22” http://www.ceantar.org/Dicts/MB2/mb22. html#MB.I 09-03-1996 <Pha‟draig> - Padraig “Index of Names in Irish Annals: Masculine Given Names” http://www.s- gabriel.org/names/mari/AnnalsIndex/Masculine/1201-1300.shtml 03/04/2005 2) Angélique le Wolfe. (Wiesenfeuer, Barony of) Resubmitted Name. Resubmitted Device. Gules, chaussé countermine, fimbriated argent, a pair of wings conjoined in lure argent. Ansteorran Internal Letter of Intent 2009-06 Submission History: [Name] Angéle le Wolfe was returned 06/08 for insufficient documentation of <Angele> in period. Submission History: [Device] Ermine sable with tails argent, on a pile gules, wings argent was returned for lack of a name 06/08. Additionally, this needs a complete redraw: whether this is meant to be a chaussé field division or an incorrectly drawn pile, the contrast is poor and cause for return; the ermine spots look odd and are too many and too small; and the wings need to be drawn better as well. Please see the commentary for details! [Asterisk Note: I recolored the red because it did not scan well.] Major Changes: No. -

American City Flags, Part 1

Akron, Ohio 1 Akron, Ohio Population Rank: U.S..... # 81 Ohio...... # 5 Proportions: 3:5 (usage) Adopted: March 1996 (official) DESIGN: Akron’s flag has a white field with the city seal in the center. The seal features an American shield, which recalls the design of the All-America City program’s shield, awarded to cities meeting the pro- gram criteria. Akron’s shield is divided roughly into thirds horizontally. At the top of the shield are two rows of five white five-pointed stars on a dark blue field. In the center section is AKRON in black on white. The lower third displays six red and five white vertical stripes. Around the shield and the white field on which it rests is a dark blue ring on which 1981-ALL-AMERICA CITY-1995 curves clockwise above, and CITY OF INVENTION curves counterclockwise below, all in white. 2 American City Flags SYMBOLISM: Akron, having twice won the distinction of “All-America City” (in 1981 and 1995), has chosen to pattern its seal to commemo- rate that award. The ten stars represent the ten wards of the city. CITY OF INVENTION refers to Akron as home to the National Inventor’s Hall of Fame at Inventure Place, a museum of inventors and inven- tions. HOW SELECTED: Prepared by the mayor and his chief of staff. DESIGNER: Mayor Don Plusquellic and his chief of staff, Joel Bailey. FORMER FLAG: Akron’s former flag also places the city seal in the center of a white field. That former logo-type seal is oval, oriented horizontally. -

The Following Items Have Been Registered: Æthelmearc

ACCEPTANCES Page 1 of 16 May 2013 LoAR THE FOLLOWING ITEMS HAVE BEEN REGISTERED: ÆTHELMEARC Hrefna in heppna Þorgrímsdóttir. Release of badge. Or, a bird displayed vert within a bordure rayonny sable. Mathias Mendel. Release of name and device. Per fess gules and vert, on a fess embattled Or three suns sable. Roana d’Evreux. Release of badge. (Fieldless) A tree eradicated per pale purpure and sable. ANSTEORRA Andreas von Meißen. Alternate name ‘Ali ibn Ja‘far al-Tayyib. Appearing on the Letter of Intent as ‘Ali ibn Ja’far al-Tayyib, the patronym should be Ja‘far, not Ja’far. Both ‘Ali and Ja‘far use the same letter, ‘ayn, while the system which uses ‘ and ’ uses ’ for hamza. The submitter used the correct forms for the letter, but the Letter of Intent did not. We have restored the name to its submitted form. The submitter requested authenticity for late 12th or early 13th century Ayyubid Arab. A man named ‘Ali ibn Ja‘far was involved in mid-12th century shipping on the Indian Ocean (in Shelomo Dov Goitein’s India Traders of the Middle Ages: Documents from the Cairo Geniza). The byname al-Tayyib appears in the same source in the later 12th century. Thus, the name meets his authenticity request. Andreas von Meißen. Badge. (Fieldless) On an eagle Or a seeblatt per pale gules and argent. Éibhilín inghean Shéafraid. Name. Submitted as Éibhleann inghean Séafraid, the given name uses a modern spelling. The period spelling is Eibhilín. Additionally, the byname must be lenited because of Gaelic grammar, making it inghean Shéafraid. -

The Palace of Pleasure; Elizabethan Versions of Italian and French

THE alace of IHleasure ELIZABETHAN VERSIONS OF ITALIAN AND FRENCH NOVELS FROM BOCCACCIO, BANDELLO, CINTHIO, STRAPAROLA, QUEEN MARGARET OF NAVARRE, AND OTHERS DONE INTO ENGLISH BY WILLIAM PAINTER NOW AGAIN EDITED FOR THE FOURTH TIME BY JOSEPH JACOBS VOL. HI. LONDON: PUBLISHED BY DAVID NUTT IN THE STRAND a, MDCCCXC TABLE OF CONTENTS. VOLUME III. TOME II.— Continued. TITLE PAGE (EDITION 1 580) CJe 53alace of Peasure^ THE TWENTY-THIRD NOUELL. The infortunate manage of a Gentleman, called Antonio Bologna, wyth the Duchejfe of Malfi, and the pitifull death of them loth. The great Honor and authority men haue in thys World, and the greater their eftimation is, the more fenfible and notorious are the faultes by theim committed, and the greater is their flaunder. In lyke manner more difficult it is for that man to tolerate and fus- tayne Fortune, which al the dayes of his life hath lyued at his eafe, if by chaunce he fall into any great neceffity than for hym whych neuer felt but woe, mifliap, and aduerfity. Dyonifius the Tyraunt of Scicilia, felt greater payne when hee was expelled his Kyng- dome, than Milo did, beinge banifhed from Rome: for fo mutch as the one was a Soueraygne Lorde, the fonne of a Kynge, a lufticiary on Earth, and the other but a fimple Citizen of a Citty, wherein the People had Lawes, and the Lawes of Magis- trates were had in reuerence. So lykewyfe the fall of a high and lofty Tree, maketh greater noyfe, than that whych is low and little. Hygh Towers, and ftately Palaces of Prynces bee feene further of, than the poore Cabans, and homely Sheepe- heardes Sheepecotes : the Walles of lofty Cittyes more a loofe doe Salute the Viewers of the fame, than the fimple Caues, which the Poore doe digge belowe theMountayneRockes. -

UC San Diego UC San Diego Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC San Diego UC San Diego Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Adaptive Design & Optimization of 3D Printable, Shape-Changing, Ballistically Deployable Drone Platforms Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/8905d3kh Author Henderson, Luke Warby Publication Date 2017 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO Adaptive Design & Optimization of 3D Printable, Shape-Changing, Ballistically Deployable Drone Platforms A thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Master of Science in Structural Engineering by Luke Henderson Committee in charge: Professor Falko Kuester, Chair Professor Thomas Bewley Professor John B. Kosmatka 2017 Copyright Luke Henderson, 2017 All rights reserved. The thesis of Luke Henderson is approved, and it is accept- able in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: Chair University of California, San Diego 2017 iii EPIGRAPH Design is not just what it looks like and feels like. Design is how it works. —Steve Jobs iv TABLE OF CONTENTS Signature Page . iii Epigraph . iv Table of Contents . v List of Figures . vii Acknowledgements . viii Vita ......................................... ix Abstract of the Thesis . x Chapter 1 Introduction . 1 Chapter 2 Concept Development . 4 2.1 Related Work . 4 2.1.1 Unmanned Aerial Vehicles . 4 2.1.2 Biomimicry . 6 2.1.3 Optimization . 6 2.1.4 multi-disciplinary optimization . 9 2.2 Possible Application Scenarios . 10 2.2.1 Adaptive Design and 3D printing . 11 2.2.2 Ground Launched Air Deployed . 13 2.2.3 High Altitude Low Opening . 14 2.2.4 Folding platform / small footprint . -

Ansteorran College of Heralds Does Estrill Indented, Not Dancetty

ANSTEORRAN COLLEGE OF [Device] Missing comma after field tincture in HERALDS blazon. Lovely arms! Collated Commentary on ILoI 0311 Gawain [Device] The chief, having only one edge, is Unto the Ansteorran College of Heralds does Estrill indented, not dancetty. I’d have drawn the Swet, Retiarius Pursuivant, make greetings. dogs and flowers a bit larger, but this should be For information on commentary submission formats or OK. to receive a copy of the collated commentary, you can contact me at: Da’ud Deborah Sweet [Device] There is nothing markedly either “Irish” 824 E 8th, Stillwater, OK 74074 or “hound”-like about these wolves. 405/624-9344 (before 10pm) “Dancetty: Applies only to a two-sided ordinary [email protected] (such as a pale or fess) which zig-zags or “dances” across the field. Indeed, a fess dancetty may be blazoned simply as a dance. Commenters for this issue: Modern non-SCA heraldic treatises define dancetty as a larger version of indented, but Knute period blazons do not make this distinction.” (Glossary of Terms) The chief here is indented. Aryanhwy merch Catmael – Herald-at-Large, Northshield, Midrealm Seawinds [Device] Vert, three irish wolfounds passant, on a Gawain of Miskbridge - Green Anchor Herald chief dancetty Or three cinquefoils vert. Da’ud ibn Auda - al-Jamal Herald Magnus [Device] The chief should be blazoned as Seawinds Heraldry Guild - Jayme Dominguez del indented. Valle, Pursuivant Extraordinary; Fearghus Cochrane, Deputy Pursuivant; Marguerite du College Action Bois; Caitriona inghean Mhic Lochlainn; Moira Device: Cochrane. Conflict Checking done via the Online Ordinary. Magnus von Lübeck – Orle Herald 2. -

Name, a Novel

NAME, A NOVEL toadex hobogrammathon /ubu editions 2004 Name, A Novel Toadex Hobogrammathon Cover Ilustration: “Psycles”, Excerpts from The Bikeriders, Danny Lyon' book about the Chicago Outlaws motorcycle club. Printed in Aspen 4: The McLuhan Issue. Thefull text can be accessed in UbuWeb’s Aspen archive: ubu.com/aspen. /ubueditions ubu.com Series Editor: Brian Kim Stefans ©2004 /ubueditions NAME, A NOVEL toadex hobogrammathon /ubueditions 2004 name, a novel toadex hobogrammathon ade Foreskin stepped off the plank. The smell of turbid waters struck him, as though fro afar, and he thought of Spain, medallions, and cork. How long had it been, sussing reader, since J he had been in Spain with all those corkoid Spanish medallions, granted him by Generalissimo Hieronimo Susstro? Thirty, thirty-three years? Or maybe eighty-seven? Anyhow, as he slipped a whip clap down, he thought he might greet REVERSE BLOOD NUT 1, if only he could clear a wasp. And the plank was homely. After greeting a flock of fried antlers at the shevroad tuesday plied canticle massacre with a flash of blessed venom, he had been inter- viewed, but briefly, by the skinny wench of a woman. But now he was in Rio, fresh of a plank and trying to catch some asscheeks before heading on to Remorse. I first came in the twilight of the Soviet. Swigging some muck, and lampreys, like a bad dram in a Soviet plezhvadya dish, licking an anagram off my hands so the ——— woundn’t foust a stiff trinket up me. So that the Soviets would find out.