Uofcpress Canadiantelevision

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Special Studies Series Foreign Nations

This item is a finding aid to a ProQuest Research Collection in Microform. To learn more visit: www.proquest.com or call (800) 521-0600 This product is no longer affiliated or otherwise associated with any LexisNexis® company. Please contact ProQuest® with any questions or comments related to this product. About ProQuest: ProQuest connects people with vetted, reliable information. Key to serious research, the company has forged a 70-year reputation as a gateway to the world’s knowledge – from dissertations to governmental and cultural archives to news, in all its forms. Its role is essential to libraries and other organizations whose missions depend on the delivery of complete, trustworthy information. 789 E. Eisenhower Parkway ■ P.O Box 1346 ■ Ann Arbor, MI 48106-1346 ■ USA ■ Tel: 734.461.4700 ■ Toll-free 800-521-0600 ■ www.proquest.com A Guide to the Microfilm Edition of THE SPECIAL STUDIES SERIES FOREIGN NATIONS The Middle East War in Iraq 2003–2006 A UPA Collection from Cover: Neighborhood children follow U.S. army personnel conducting a patrol in Tikrit, Iraq, on December 27, 2006. Photo courtesy of U.S. Department of Defense Visual Information Center (http://www.dodmedia.osd.mil/). The Special Studies Series Foreign Nations The Middle East War in Iraq 2003–2006 Guide by Jeffrey T. Coster A UPA Collection from 7500 Old Georgetown Road Bethesda, MD 20814-6126 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data The Middle East war in Iraq, 2003–2006 [microform] / project editors, Christian James and Daniel Lewis. microfilm reels ; 35 mm. – (Special studies series, foreign nations) Summary: Reproduces reports issued by U.S. -

Beryllium Diffusion of Ruby and Sapphire John L

VOLUME XXXIX SUMMER 2003 Featuring: Beryllium Diffusion of Rubies and Sapphires Seven Rare Gem Diamonds THE QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF THE GEMOLOGICAL INSTITUTE OF AMERICA Summer 2003 VOLUME 39, NO. 2 EDITORIAL _____________ 83 “Disclose or Be Disclosed” William E. Boyajian FEATURE ARTICLE _____________ pg. 130 84 Beryllium Diffusion of Ruby and Sapphire John L. Emmett, Kenneth Scarratt, Shane F. McClure, Thomas Moses, Troy R. Douthit, Richard Hughes, Steven Novak, James E. Shigley, Wuyi Wang, Owen Bordelon, and Robert E. Kane An in-depth report on the process and characteristics of beryllium diffusion into corundum. Examination of hundreds of Be-diffused sapphires revealed that, in many instances, standard gemological tests can help identify these treated corundums. NOTES AND NEW TECHNIQUES _______ 136 An Important Exhibition of Seven Rare Gem Diamonds John M. King and James E. Shigley A look at the background and some gemological observations of seven important diamonds on display at the Smithsonian Institution from June to September 2003, in an exhibit titled “The Splendor of Diamonds.” pg. 137 REGULAR FEATURES _____________________ 144 Lab Notes • Vanadium-bearing chrysoberyl • Brown-yellow diamonds with an “amber center” • Color-change grossular-andradite from Mali • Glass imitation of tsavorite • Glass “planetarium” • Guatemalan jade with lawsonite inclusions • Chatoyant play-of-color opal • Imitation pearls with iridescent appearance • Sapphire/synthetic color-change sapphire doublets • Unusual “red” spinel • Diffusion-treated tanzanite? -

Park Pavilions”

! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Architectural !Design !Competition ! PARK !PAVILIONS ! for ! BORDEN !PARK ! CASTLE !DOWNS !PARK ! JOHN !FRY !SPORTS !PARK ! MILL !WOODS !SPORTS !PARK ! VICTORIA !PARK ! ! ! ! (is !in !the !process !of !being) !SANCTIONED !BY !THE !ALBERTA !ASSOCIATION !OF ! ARCHITECTS !! ! City of Edmonton Parks Amenities Buildings Competitions Page 1 of 30 ! PROJECT !NUMBER: ! ! CP R2240 ! Close !of !Registration: ! March !01, !2011 ! Deadline !for !Entries: ! March !22, !2011 !before !2:00 !pm, !local !time ! ! ! TABLE !OF !CONTENTS ! ! LIST !OF !DOCUMENTS ! Cover !Page ! Table !of !Contents ! Introduction !and !General !Information ! Competition !Background ! Instructions !and !Guidelines ! ATTACHED !DOCUMENTS ! City !of !Edmonton !Draft !Professional !Services !Agreement ! City !of !Edmonton !General !Terms !for !Construction ! City !of !Edmonton !CAD !Standards !&!Consultant !Deliverables !Manual ! City !of !Edmonton !Checklist !for !Accessibility !&!Universal !Design !in !Architecture ! City of Edmonton Parks Amenities Buildings Competitions Page 2 of 30 INTRODUCTION !AND !GENERAL !INFORMATION ! LIST !OF !REFERENCE !MATERIAL !(AVAILABLE !ON !SECURE !SITE !FOR !DOWNLOAD !AFTER !REGISTRATION) ! General !Information ! This !Competition !Brief ! City !of !Edmonton !–!Draft !Professional !Services !Agreement ! City !of !Edmonton !–!General !Terms !for !Construction ! Borden !Park !Information ! Air !Photos ! Site !Photos ! Borden !Park !Building !! Program ! Borden !Park !Site !Cadastral !–!AutoCAD !file ! Borden !Park !Site -

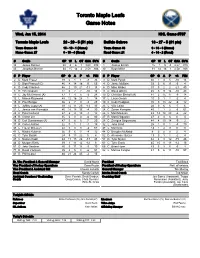

Toronto Maple Leafs Game Notes

Toronto Maple Leafs Game Notes Wed, Jan 15, 2014 NHL Game #707 Toronto Maple Leafs 23 - 20 - 5 (51 pts) Buffalo Sabres 13 - 27 - 5 (31 pts) Team Game: 49 15 - 10 - 1 (Home) Team Game: 46 9 - 13 - 3 (Home) Home Game: 27 8 - 10 - 4 (Road) Road Game: 21 4 - 14 - 2 (Road) # Goalie GP W L OT GAA SV% # Goalie GP W L OT GAA SV% 34 James Reimer 20 8 6 1 3.08 .918 1 Jhonas Enroth 15 1 9 4 2.57 .913 45 Jonathan Bernier 34 15 14 4 2.58 .926 30 Ryan Miller 31 12 18 1 2.58 .928 # P Player GP G A P +/- PIM # P Player GP G A P +/- PIM 2 D Mark Fraser 19 0 1 1 -8 33 3 D Mark Pysyk 40 1 4 5 -10 14 3 D Dion Phaneuf (C) 46 4 14 18 9 65 4 D Jamie McBain 33 3 6 9 -5 4 4 D Cody Franson 46 2 19 21 -11 18 6 D Mike Weber 31 0 2 2 -21 40 8 D Tim Gleason 22 0 2 2 -10 14 9 C Steve Ott (C) 45 5 9 14 -16 43 11 C Jay McClement (A) 47 1 4 5 -2 24 10 D Christian Ehrhoff (A) 44 2 15 17 -9 18 12 L Mason Raymond 48 12 16 28 1 14 17 L Linus Omark 10 0 1 1 -2 4 15 D Paul Ranger 36 2 7 9 -8 28 19 C Cody Hodgson 35 9 13 22 -9 12 19 L Joffrey Lupul (A) 39 14 11 25 -13 35 23 L Ville Leino 28 0 6 6 -7 6 21 L James van Riemsdyk 46 18 18 36 -4 30 24 C Zenon Konopka 40 1 1 2 -6 61 24 C Peter Holland 27 6 4 10 -1 12 26 L Matt Moulson 43 14 14 28 -6 22 28 R Colton Orr 35 0 0 0 -6 80 27 R Matt D'Agostini 27 2 4 6 0 4 36 D Carl Gunnarsson (A) 47 0 6 6 7 20 28 C Zemgus Girgensons 44 4 10 14 -9 2 37 R Carter Ashton 22 0 1 1 -1 19 32 L John Scott 25 1 0 1 -8 70 38 L Frazer McLaren 22 0 0 0 -3 67 37 L Matt Ellis 13 1 2 3 0 0 41 L Nikolai Kulemin 36 5 6 11 -4 12 44 D Brayden McNabb 9 0 0 0 2 4 42 C Tyler Bozak 24 9 13 22 5 4 52 D Alexander Sulzer 13 0 1 1 -2 4 43 C Nazem Kadri 44 11 15 26 -13 43 57 D Tyler Myers 42 4 8 12 -15 46 44 D Morgan Rielly 39 1 11 12 -12 8 63 C Tyler Ennis 45 10 8 18 -12 16 51 D Jake Gardiner 46 3 11 14 -3 10 65 C Brian Flynn 43 3 3 6 -5 4 71 R David Clarkson 35 3 5 8 -6 51 82 L Marcus Foligno 41 5 6 11 -10 57 81 R Phil Kessel 48 21 24 45 -2 15 Sr. -

Sport-Scan Daily Brief

SPORT-SCAN DAILY BRIEF NHL 1/2/2020 Anaheim Ducks Detroit Red Wings 1168875 Why the Ducks’ youth movement could be costing them 1168903 Detroit sports in the 2010s was a decade to forget. But victories let's see how much you remember 1168904 Physical play, fighting spirit a winning formula for Red Arizona Coyotes Wings 1168876 Coyotes recall D Kyle Capobianco, assign Aaron Ness to 1168905 Red Wings aim to maintain grittier disposition second half Tucson of season 1168877 Coyotes’ penalty kills, timely goals lead to much-needed win over Blues Edmonton Oilers 1168878 Updated 10 bold predictions: Me vs. Mrs. Rita’s 1168906 Klefbom hurt against the Rangers but how bad is it? 1168907 Hats off to James Neal who likes to score three Boston Bruins 1168908 Lowetide: A shift-by-shift analysis of Kailer Yamamoto’s 1168879 The bests and worsts for the Bruins in the season’s first 2019-20 debut in the Oilers’ New Year’s Eve game half 1168880 Bruins need more help from rest of lineup Florida Panthers 1168881 The 12 biggest Boston sports stories of the 2010s 1168909 Blue Jackets’ Werenski, Merzlikins spoil Bobrovsky’s 1168882 What we learned in Bruins' 3-2 shootout loss to the Devils return to Columbus 1168910 An Elvis rockin’ eve: Sergei Bobrovsky’s emotional return Buffalo Sabres to Columbus ends in a Blue Jackets’ party 1168883 Sabres' Evan Rodrigues does not deny he wants a fresh start elsewhere Los Angeles Kings 1168884 Five years later, Sabres and Oilers have given Jack Eichel 1168911 WORLD JUNIORS UPDATE, PHILLIPS, MACDERMID and Connor McDavid -

Examining Our Christian Heritage 2

_____________________________________________________________________________________ Student Guide Examining Our Christian Heritage 2 Clergy Development Church of the Nazarene Kansas City, Missouri 816-333-7000 ext. 2468; 800-306-7651 (USA) 2004 ____________________________________________________________________________________ Copyright ©2004 Nazarene Publishing House, Kansas City, MO USA. Created by Church of the Nazarene Clergy Development, Kansas City, MO USA. All rights reserved. All scripture quotations are from the Holy Bible, New International Version (NIV). Copyright 1973, 1978, 1984 by the International Bible Society. Used by permission of Zondervan Publishing House. All rights reserved. NASB: From the American Standard Bible (NASB), copyright the Lockman Foundation 1960, 1962, 1963, 1968, 1971, 1972, 973, 1977, 1995. Used by permission. NRSV: From the New Revised Standard Version of the Bible, copyright 1989 by the Division of Christian Education of the National Council of the Churches of Christ in the U.S.A. Used by permission. All rights reserved. Notice to educational providers: This is a contract. By using these materials you accept all the terms and conditions of this Agreement. This Agreement covers all Faculty Guides, Student Guides, and instructional resources included in this Module. Upon your acceptance of this Agreement, Clergy Development grants to you a nonexclusive license to use these curricular materials provided that you agree to the following: 1. Use of the Modules. • You may distribute this Module in electronic form to students or other educational providers. • You may make and distribute electronic or paper copies to students for the purpose of instruction, as long as each copy contains this Agreement and the same copyright and other proprietary notices pertaining to the Module. -

33313331MAY 12TH CATALOG.Pdf

Sensational Home Furnishings,High End Liquor & Collectibles 5/12/2019 LOT # LOT # 1 WELCOME TO THE KASTNER AUCTIONS EXPERIENCE 8 1958 CANADA SILVER HALF DOLLAR (COLLECTABLES) 1a FEATURED: SOJIN BABY GRAND PIANO! SEARCH LOT 326 TO BID. 9 2014 $20 ROYAL CANADIAN MINT MAJESTIC MAPLE 1b FEATURED: ALCOHOL! COIN. SEARCH LOTS 101-125, 201-225, 301-325, 401-425, 501-525, (COLLECTABLES) 601-625, 701-725, 801-825, 901-925, 1001-1004 TO BID. 10 2012 $20 FINE SILVER COIN: ROBERT BATEMAN - BULL MOOSE (COLLECTABLES) 1c FEATURED: VEHICLES! SEARCH LOTS 328, 332, 336, 340, 347-349 TO BID. 11 2014 $20 ROYAL CANADIAN MINT MAPLE CANOPY 1d FEATURED: SPORTS MEMORABILIA! COIN SEARCH LOTS 333, 788-793, 935, 937-953 TO BID. (COLLECTABLES) 1e FEATURED: 1983 GMC CUTAWAY MOTORHOME! 12 2007 .25 CENT RUBY THROATED HUMMINGBIRD SEARCH LOT 344 TO BID. (COLLECTABLES) 1f FEATURED: CRYSTAL AND CHINA SETS! 13 2014 $20 FINE SILVER COIN: THE BISON FAMILY - A SEARCH LOTS 357-362, 886, 887, 892, 893 TO BID. FAMILY AT REST (COLLECTABLES) 1g FEATURED: ESTATE FURNISHINGS! 14 2004 .50 CENT STERLING SILVER COIN: TIGER SEARCH LOTS 737, 782, 845-848, 855-857, 859-864, 877, 889, SWALLOWTAIL (COLLECTABLES) 960, 967, 992, 1033-1038, 1044, 1045, 1058, 1059, 1062, 1078 TO 15 2013 .25 CENT COLOURED COIN: PURPLE BID, CONEFLOWER AND EASTER TAILED BLUE (COLLECTABLES) 1h FEATURED: APPLIANCES! LOTS 375-396 TO BID. 16 150th ANNIVERSARY OF TORONTO (1834 - 1984) 1i FEATURED: SOFA SETS AND SECTIONALS! SILVER SEARCH LOTS 556-558, 664, 766, 767, 786, 957, 993 TO BID. DOLLAR (COLLECTABLES) 1j FEATURED: -

Canadian Television Today

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository University of Calgary Press University of Calgary Press Open Access Books 2006 Canadian Television Today Beaty, Bart; Sullivan, Rebecca University of Calgary Press Beaty, B. & Sullivan, R. "Canadian Television Today". Series: Op/Position: Issues and Ideas series, No. 1. University of Calgary Press, Calgary, Alberta, 2006. http://hdl.handle.net/1880/49311 book http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/ Attribution Non-Commercial No Derivatives 3.0 Unported Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca University of Calgary Press www.uofcpress.com CANADIAN TELEVISION TODAY by Bart Beaty and Rebecca Sullivan ISBN 978-1-55238-674-3 THIS BOOK IS AN OPEN ACCESS E-BOOK. It is an electronic version of a book that can be purchased in physical form through any bookseller or on-line retailer, or from our distributors. Please support this open access publication by requesting that your university purchase a print copy of this book, or by purchasing a copy yourself. If you have any questions, please contact us at [email protected] Cover Art: The artwork on the cover of this book is not open access and falls under traditional copyright provisions; it cannot be reproduced in any way without written permission of the artists and their agents. The cover can be displayed as a complete cover image for the purposes of publicizing this work, but the artwork cannot be extracted from the context of the cover of this specific work without breaching the artist’s copyright. COPYRIGHT NOTICE: This open-access work is published under a Creative Commons licence. -

Bakalářská Práce

MASARYKOVA UNIVERZITA Fakulta sportovních studií Katedra spole čenských v ěd a managementu sportu Marketing NHL Bakalá řská práce Vedoucí bakalá řské práce: Vypracoval: Mgr. Viktor Pruša Mat ěj Šidák Management cestovního ruchu Brno, 2014 Prohlašuji, že jsem bakalá řskou práci vypracoval samostatn ě a na základ ě literatury a pramen ů uvedených v použitých zdrojích. V Brn ě dne 28. dubna 2014 ..................................... Zde bych rád pod ěkoval svému vedoucímu Mgr. Viktoru Prušovi za odborné vedení bakalá řské práce, za cenné rady a p řipomínky k práci. Obsah ÚVOD ..................................................................................................................... 6 1 LITERÁRNÍ P ŘEHLED ................................................................................. 7 1.1 Marketing ................................................................................................. 7 1.1.1 Marketingový mix ............................................................................. 8 1.1.2 Marketingová komunikace ................................................................ 9 1.1.3 Sportovní marketing ........................................................................ 11 1.1.4 Internet marketing ........................................................................... 13 1.2 Masmédia ............................................................................................... 14 1.2.1 Televizní vysílání ............................................................................ 15 1.2.2 Internet ........................................................................................... -

Wayne Gretzky from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Wayne Gretzky From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Wayne Douglas Gretzky , OC (/ ˈɡrɛtski/; born January 26, 1961) is a Canadian former professional ice hockey player and former head coach. He played 20 seasons in the National Hockey League (NHL) for four teams from 1979 to 1999. Wayne Gretzky Nicknamed "The Great One" , he has been called "the greatest hockey player ever" [1] by many sportswriters, players, and Hockey Hall of Fame, 1999 the NHL itself. He is the leading point-scorer in NHL history, with more assists than any other player has points, and is the only NHL player to total over 200 points in one season – a feat he accomplished four times. In addition, he tallied over 100 points in 16 professional seasons, 14 of them consecutive. At the time of his retirement in 1999, he held 40 regular- season records, 15 playoff records, and six All-Star records. He won the Lady Byng Trophy for sportsmanship and performance five times, [2] and he often spoke out against fighting in hockey. [1][3] Born and raised in Brantford, Ontario, Gretzky honed his skills at a backyard rink and regularly played minor hockey at a level far above his peers. [4] Despite his unimpressive stature, strength and speed, Gretzky's intelligence and reading of the game were unrivaled. He was adept at dodging checks from opposing players, and he could consistently anticipate where the puck was going to be and execute the right move at the right time. Gretzky also became known for setting up behind Wayne Gretzky in 2001 his opponent's net, an area that was nicknamed "Gretzky's office". -

First Sports

First Sports First Sports eLITEFINe Online Shopping System - Product Listing Page Sitemap eLITEFINe Reverse Susan B. Anthony (1979 -1981, 1999) Two Tone Rope Bezel U.S. Coin with 24' Chain Shopping Form Reverse Washington Quarter (1932-1998) Two Tone U.S. Coin Cut Out Tie Tack Reverse Kennedy Half Dollar (1970-Date) Two Tone U.S. Coin Cut Out Tie Tack Terms Delaware Two Tone Statehood Quarter Hinged Money Clip Pennsylvania Two Tone Statehood Quarter Hinged Money Clip New Jersey Two Tone Statehood Quarter Hinged Money Clip Georgia Two Tone Statehood Quarter Hinged Money Clip Featured Site Connecticut Two Tone Statehood Quarter Hinged Money Clip Massachusetts Two Tone Statehood Quarter Hinged Money Clip Maryland Two Tone Statehood Quarter Hinged Money Clip South Carolina Two Tone Statehood Quarter Hinged Money Clip New Hampshire Two Tone Statehood Quarter Hinged Money Clip Virginia Two Tone Statehood Quarter Hinged Money Clip New York Two Tone Statehood Quarter Hinged Money Clip North Carolina Two Tone Statehood Quarter Hinged Money Clip Shopping Portal Rhode Island Two Tone Statehood Quarter Hinged Money Clip Vermont Two Tone Statehood Quarter Hinged Money Clip Kentucky Two Tone Statehood Quarter Hinged Money Clip Tennessee Two Tone Statehood Quarter Hinged Money Clip designed by Ohio Two Tone Statehood Quarter Hinged Money Clip Louisiana Two Tone Statehood Quarter Hinged Money Clip Indiana Two Tone Statehood Quarter Hinged Money Clip Mississippi Two Tone Statehood Quarter Hinged Money Clip Delaware Two Tone Statehood Quarter Spring Loaded -

Changing Narratives of the Mountain Meadows Massacre in Utah's Public School Curricula

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU All Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies 5-2013 The Evolution of History: Changing Narratives of the Mountain Meadows Massacre in Utah's Public School Curricula Casey W. Olson Utah State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd Part of the Education Commons Recommended Citation Olson, Casey W., "The Evolution of History: Changing Narratives of the Mountain Meadows Massacre in Utah's Public School Curricula" (2013). All Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 2071. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd/2071 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE EVOLUTION OF HISTORY: CHANGING NARRATIVES OF THE MOUNTAIN MEADOWS MASSACRE IN UTAH’S PUBLIC SCHOOL CURRICULA by Casey W. Olson A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in Education Approved: Steven P. Camicia, Ph.D. Cindy D. Jones, Ph.D. Major Professor Committee Member Philip L. Barlow, Th.D. Keri Holt, Ph.D. Committee Member Committee Member Barry M. Franklin, Ph.D. Mark R. McLellan, Ph.D. Committee Member Vice President for Research and Dean of the School of Graduate Studies UTAH STATE UNIVERSITY Logan, Utah 2013 Copyright © Casey W. Olson 2013 ii All rights reserved iii ABSTRACT The Evolution of History: Changing Narratives of the Mountain Meadows Massacre in Utah’s Public School Curricula by Casey W.