Remotely Operated Vehicles—An Overview

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter 2. Electrical Theory

Open Research Online The Open University’s repository of research publications and other research outputs Theoretical and Experimental Investigations Into Umbilical Cables for Communications Under the Sea Thesis How to cite: Mitchell, Andrew George Cairncross (2014). Theoretical and Experimental Investigations Into Umbilical Cables for Communications Under the Sea. PhD thesis The Open University. For guidance on citations see FAQs. c 2014 A.G.C. Mitchell Version: Version of Record Link(s) to article on publisher’s website: http://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21954/ou.ro.00009a49 Copyright and Moral Rights for the articles on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. For more information on Open Research Online’s data policy on reuse of materials please consult the policies page. oro.open.ac.uk Thesis: Theoretical and Experimental Investigations Into Umbilical Cables for Communications Under the Sea Author: Andrew George Cairncross Mitchell BSc. (Hons.) Electronics and Microprocessor Engineering, University of Strathclyde, 1984 Thesis: Theoretical and Experimental Investigations Into Umbilical Cables for Communications Under the Sea Submitted for PhD, 30th September 2012 The Open University Faculty of Mathematics, Computing and Technology Thesis: Theoretical and Experimental Investigations Into Umbilical Cables for Communications Under the Sea Thesis: Theoretical and Experimental Investigations Into Umbilical Cables for Communications Under the Sea Abstract Continual advances are being made in the control and monitoring of subsea oil wells by the application of new technology for sensors, subsea processing and communications devices. With these advances, the demands on the subsea umbilical are constantly increasing with deployment lengths and depths growing and the quantity of controlled functions now greater than ever. -

Ss521-Ah-Pro-010 0910-Lp-103-2583 Revision 1

Downloaded from http://www.everyspec.com SS521-AH-PRO-010 0910-LP-103-2583 REVISION 1 TECHNICAL MANUAL U.S. NAVY DIVING UMBILICAL (UBA MK 20 AND MK 21) DESCRIPTION, MATERIALS, AND ASSEMBLY GPC, A Joint Venture Contract N00024-01-D-4018 SUPERSEDES: SS521-AH-PRO-010, APRIL 1997. DISTRIBUTION STATEMENT A: APPROVED FOR PUBLIC RELEASE; DISTRIBUTION UNLIMITED. PUBLISHED BY DIRECTION OF COMMANDER, NAVAL SEA SYSTEMS COMMAND. Downloaded from http://www.everyspec.com Downloaded from http://www.everyspec.com SS521-AH-PRO-010 0910-LP-103-2583 REVISION 1 TECHNICAL MANUAL U.S. NAVY DIVING UMBILICAL (UBA MK 20 AND MK 21) DESCRIPTION, MATERIALS, AND ASSEMBLY GPC, A Joint Venture Contract N00024-01-D-4018 SUPERSEDES: SS0521-AH-PR0-010, APRIL 1997. DISTRIBUTION STATEMENT A: APPROVED FOR PUBLIC RELEASE; DISTRIBUTION UNLIMITED. PUBLISHED BY DIRECTION OF COMMANDER, NAVAL SEA SYSTEMS COMMAND. 24 FEBRUARY 2005 Downloaded from http://www.everyspec.com SS521-AH-PRO-010 LIST OF EFFECTIVE PAGES Date of Issue: Original ...........................................................0.................................................................... April 15, 1997 Revision ..........................................................1.............................................................. February 24, 2005 Total number of pages in this publication is 75, consisting of the following: Page No. Change No. Title and A ...................................................................................................................................................1 Change -

Technology and Oceanography

Chapter 3 Discussion of Technologies Contents Page Introduction . 41 12. Number of Ships Reaching Age 25 in Oceanographic Ships. ..., . 41 Next 20 years. 51 Manned Submersibles and ROVs , . 42 13. Length and Age Characteristics of Buoy, Moored, and Ocean-Floor Systems . 42 Major World Oceanographic Research Equipment and Instrumentation . 43 Fleets . 52 Satellites . 43 14, Oceanographic Fleet Replacement Aircraft . 44 Cost Estimates in Millions of Dollars in Oceanic Data Systems . 44 the Next 20 Years. 53 15. Oceanographic Fleet Operating Cost Ships . 46 Comparison. 53 Current Uses . 50 16. Academic and NOAA Fleet Age.., . 50 Comparison of Daily Ship Operating Size and Length Comparison With Foreign costs . 53 Oceanographic Fleets. 50 17. Federally Owned and Operated U.S. Costs . , . 52 Submersibles. 64 Present and Future Plans for Ships. 53 18. Costs for Navy Submersibles. 64 Alternative Plans for Future Ship Operations ..,. 59 19. U.S. Private-Sector Submersibles . 69 Submersibles . 64 20. Foreign Government-Supported Manned Submersibles . 64 Submersibles. 70 Comparison of Submersible Capabilities. 70 21. Foreign Private-Sector Submersibles. 71 Remotely Operated Vehicles . 72 22. ROV Applications. 73 23. U.S. Government-Supported ROVs . 73 Buoy, Moored, and Ocean-Floor Systems . 75 24. U.S. Satellites of Utility in Ocean, Buoys . 75 Coastal, and Polar Monitoring. 91 Moored Systems. , . , . ,. 78 25. Measurement Needs for Ocean-Floor ystems . 81 Oceanographic Satellites . 92 Other Vehicles. 82 26. Satellite Sensor Records of Interest in Equipment and Instrumentation . 84 Ocean, Coastal, and Polar Monitoring. 93 Equipment . 84 27, Geophysical Oceanographic Instrumentation . 85 Measurement Design Capabilities for Seasat-A . 99 Satellites ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● . ● ● . 91 28, Aircraft and Sensors. -

Amron 8225I-UM 2-Diver Air Control Systems User Manual REV

Instruction Manual for Amron International, Inc. Model 8225i & 8225iC-01 2-Diver Air Control Systems S/N: 1380 Aspen Way, Vista California 92081-8349 United States of America Phone: (760) 208-6500 Fax (760) 599-3857 email: [email protected] web: www.amronintl.com This manual and the information contained herein are provided for use as an operation and maintenance guide. No license or rights to manufacture, reproduce, or sell either the manual or articles described herein are given. Amron International, Inc. reserves the right to change specifications without notice. Copyright© 2021 Amron International, Inc. MODEL 8225i & 8225iC-01 USER MANUAL TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION AND SPECIFICATIONS ............................................................................................ 1 1.1 Introduction .................................................................................................................................... 1 1.2 Specifications Air Control .............................................................................................................. 2 1.3 Specifications Depth Monitoring (Pneumo) ................................................................................... 3 1.4 Specifications Communications (8225iC-01 Model Only) ............................................................. 4 1.5 Specifications Enclosure ............................................................................................................... 4 2. OPTIONS AND ACCESSORIES .......................................................................................................... -

Seeking Signals in The

$: t j ! Ij ~ ,l IOJ I ~ , I I I! 1I I 1 " Edited by Elizabeth N. Shor Layout by jo p. griffith June 1997 Published by: Marine Physical Laboratory ofthe Scripps Institution of Oceanography University of California, San Diego We gratefully acknowledge the following for use of their photographs in this publication: Christine Baldwin W. Robert Cherry Defense Nuclear Agency Fritz Goro William S. Hodgkiss Alan C. Jones MPL Photo Archives SIO Archives (UCSD) Eric T. Slater SIO Reference Series 97-5 ii Contents Introduction: How MPL Came To Be Betty Shor 1 Carl Eckart and the Marine Physical Laboratory Leonard Liebermann 6 Close Encounter of the Worst Kind Fred Fisher and Christine Baldwin 9 Early Days of Seismic and Magnetic Programs at MPL Arthur D. Raft 10 Recollections of Work at the Marine Physical Laboratory: A Non-Academic Point of View Dan Gibson 23 Capricorn Expedition, 1952 Alan C. Jones 39 Que Sera Sera R. J. Smith 42 A Beginning in Undersea Research Fred Noel Spiess ....... 46 The Value of MPL to the Navy Charles B. Bishop 51 The Outhouse Fred Fisher ....... 54 Exploring the Gulf of Alaska and Beyond George G. Shor, Jr 55 Chinook Expedition, 1956 Alan C. Jones 59 Operation HARDTACK I W. Robert Cherry 62 DELTIC and DIMUS, Two Siblings Victor C. Anderson 65 MPL and ARTEMIS Victor C. Anderson 71 Early Days of MPL Christine Baldwin 78 There's Always a Way Around the Rules George G. Shor, Jr 82 iii A Saga from Graduate Student to FLIP Fred Fisher 85 Anchoring FLIP in Deep Water Earl Bronson 95 Then There was SLIP Fred Fisher ...... -

Environmental Statement

Environmental Statement INFORMATION SHEET Project name: Beatrice Wind Farm Demonstrator Project DTI Project Reference: D/2875/2005 Type of project: Demonstration of offshore wind farm Undertaker name: Talisman Energy (UK) Limited Address: 163 Holburn Street Aberdeen AB10 6BZ Licensees/Owners: Talisman Energy (UK) Limited Anticipated commencement of works: May 2006 Short description of project: Proposed installation and operation of two stand- alone wind turbine generating units (WTGs) to provide electrical power to the Beatrice platforms. The WTGs will be supported on small steel jackets piled into the seabed, and will be 88m high with blades 63m long. The WTGs will be linked to the Beatrice AP platform by a buried umbilical containing the electrical cable. Date and reference number of any Beatrice Decommissioning Programme earlier Statement related to this RDBF/003/00006C-01 and 02 project: December 2004 Significant environmental impacts Underwater noise from piling identified: Potential interaction with birds at sea Statement prepared by: Talisman Energy (UK) Limited – 1– TALISMAN ENVIRONMENTAL STATEMENT ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Talisman is grateful for the support, advice and comments received from all organisations and individuals during the consultation programme. Thanks are due to the Moray Firth Partnership for help in organising major stakeholder meetings, and to the University of Aberdeen Lighthouse Field Station for access to unpublished data. This Environmental Statement was prepared with support from BMT Cordah Limited. Design and production by The Big Picture. – 2– CONTENTS CONTENTS 1 NON-TECHNICAL SUMMARY . .9 1.1 Introduction . .9 1.2 Description of proposed project . .10 1.3 Environmental setting for the proposed WTGs . .11 1.4 Consultation programme . -

The Daily Egyptian, November 10, 1999

Southern Illinois University Carbondale OpenSIUC November 1999 Daily Egyptian 1999 11-10-1999 The Daily Egyptian, November 10, 1999 Daily Egyptian Staff Follow this and additional works at: https://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/de_November1999 Volume 85, Issue 55 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Daily Egyptian 1999 at OpenSIUC. It has been accepted for inclusion in November 1999 by an authorized administrator of OpenSIUC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ATTENTION: ... THESE DOCUMENTS~ _FILMt:D EXACTLY · . · · AS THEY WERE RECEIVED. IN SOME CASES,, ·PAGES MAYBEDIFFICULTT0READ. SOME ... PAGES APPEART0 HVEOVERLAPPING DOCtJMENTS.r~BUT THEY WE~. PHOTOCOPIED.IN THIS.MANNER. SANDRA MAS()~' . · DIRECTOR OF RECORDS MANAGEMENT . - . - SOUTHERN ILLINOIS UNIVERSITY .. MICROORA.PfUCS DEPARJMENT CARB"OND~E, ILLINOIS · · . Internet 2: The pros and cons of advancement on the Rats: Internet. page 6 Study shows that soy . proteins prevent Spring cleaning: cardiovascular disorders Asbestos removal-from in rodents. Anthony Hall to begin . page5 in spring semester. page·3 SOlITHERN ILLJNOIS UN!VERSIIT AT CARBONDALE w,.65, i,.'<155, l6rACEl' slfi%Maili•!MP• Evezythine~ I ' r I , , i i I • I . 1 , . , ·on·n·ect- - - - ·~ - ' ..·s· - : Story bv I BRYNN Scarr I : Photos by f IPPEI WATANABE I I IEddie Swimmer, an i East Ban°d Cherokee j Indian, makes hoop ; dance designs !during a · : performance i Saturday, at Carbondale . Community High _____:>_:_ 1 School. Tearing down stere_~types was th~ f OCUS of the_: Recl/Ecigli' :--: . Alliance and: American.Indian Association'~ FaW Fesavali Seth Russell, a 12~year-old· Pima-Papago Native Jcids''parents are proba_bly th!! same kids who teased1me American, comes home day· after day crying when his when I was young." . -

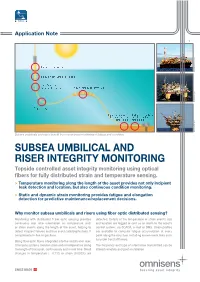

Subsea Umbilical and Riser Integrity Monitoring

Application Note 1 Sunlight - temperature © Stéphane © Bommert Bend stiffener - strain and fatigue Shock/abrasion/ clashing - temperature Buoyancy modules - temperature © Øyvind Hagen Weight - fatigue Touch-down point - Geohazard - landslide, abrasion, friction - seismic - strain/ temperature temperature © Michael Grimes Subsea umbilicals and risers benefi t from continuous monitoring of fatigue and condition. SUBSEA UMBILICAL AND RISER INTEGRITY MONITORING Topside controlled asset integrity monitoring using optical fi bers for fully distributed strain and temperature sensing. > Temperature monitoring along the length of the asset provides not only incipient leak detection and location, but also continuous condition monitoring. > Static and dynamic strain monitoring provides fatigue and elongation detection for predictive maintenance/replacement decisions. Why monitor subsea umbilicals and risers using fiber optic distributed sensing? Monitoring with distributed fi ber optic sensing provides detected. Details of the temperature or strain event’s size continuous real time information on temperature and/ and location are logged or sent as an alarm to the asset’s or strain events along the length of the asset, helping to control system, via SCADA, e-mail or SMS. Strain profi les detect incipient failures and thus avoid catastrophic loss. It are available to compute fatigue accumulation at every compliments in-line inspections. point along the structure, including known weak links such as under bend stiffeners. Using fi ber optic fi bers integrated into the umbilical or riser, Omnisens systems monitor strain and/or temperature along The frequency and type of information transmitted can be the length of that asset, continuously and in real time. Small altered remotely and post-installation. changes in temperature (± 0.1°C) or strain (0.002%) are 2 Umbilicals Umbilicals are increasing in length, weight, complexity and power transmission ability in response to deep- water production and subsea processing demand. -

Rota, Tinian See Tough ~ by Eileen 0

~--------- arianas ~riety;;~ Micronesia's Leading Newspaper Since 1972 b&) V\IS lls~Zp·i~=g~ntl Due to defeat.. of. initiatives H ~ IJmaker to put up fj ij factory in Palau !1 ~ ~ Rota, Tinian see tough ~ By Eileen 0. Tabaranza !' /.1 For the Variety ti [: KOROR(PalauHorizon)- l'i /: A Saipan-based garment /1 prospects for ec9nom.y i manufacturer has been given i; f; the green light by the Foreign l: By Haldee V. Eugenio also feared the island is heading :; Investment Board (FIB) here ::: Variety News Staff for a more difficult economic fu ; toputupa$2-milliongarment ;: LOCAL officials of Rota and ture. i: factory that will manufacture :: Tinian yesterday expressed dis "We are very disappointed with ; cotton knitted apparel for ex- 0 appointment and grave concern the results . The proposed :, port to the United States. ' " I over the defeat of their local ini amendments were the result of a · Pacific Garments would be • tiatives seeking to establish and number of months' hard work not ;; the second garment factory to improve, respectively, casino only by the task force but also by (i be put up in Palau. The first to '.· gaming in their jurisdictions. all the people who want it," Sutton ;; set up shop and take advan- : Rota Mayor Benjamin T. said in a telephone interview. ii tage ofexport quota-free treat- . Manglona said economic oppor Sutton also said it will be harder [; ment by the U.S. is Orientex !·: tunities - including more jobs for Tinian to correct loopholes in [j Palau, Inc. [: and more investors - will be the current gaming act and im t The FIB approved the ap- i'. -

Powering the Blue Economy: Exploring Opportunities for Marine Renewable Energy in Martime Markets

™ Exploring Opportunities for Marine Renewable Energy in Maritime Markets April 2019 This report is being disseminated by the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE). As such, this document was prepared in compliance with Section 515 of the Treasury and General Government Appropriations Act for fiscal year 2001 (Public Law 106-554) and information quality guidelines issued by DOE. Though this report does not constitute “influential” information, as that term is defined in DOE’s information quality guidelines or the Office of Management and Budget’s Information Quality Bulletin for Peer Review, the study was reviewed both internally and externally prior to publication. For purposes of external review, the study benefited from the advice and comments of nine energy industry stakeholders, U.S. Government employees, and national laboratory staff. NOTICE This report was prepared as an account of work sponsored by an agency of the United States government. Neither the United States government nor any agency thereof, nor any of their employees, makes any warranty, express or implied, or assumes any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of any information, apparatus, product, or process disclosed, or represents that its use would not infringe privately owned rights. Reference herein to any specific commercial product, process, or service by trade name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise does not necessarily constitute or imply its endorsement, recommendation, or favoring by the United States government or any agency thereof. The views and opinions of authors expressed herein do not necessarily state or reflect those of the United States government or any agency thereof. -

ECOS Green Report Focuses on State Environmental Agency Use of UAS,1 Actual and Potential Benefits, and Current and Planned Uses by the Spotlighted State Agencies

February 2021 GREEN REPORT State Environmental Agency Modernization — Leveraging Unmanned Aerial Systems to Improve Environmental Results By Paulina Lopez-Santos, Project Associate, under the direction of Beth Graves, Executive Project Manager, Environmental Council of the States (ECOS) Copyright ©2021 by the Environmental Council of the States INTRODUCTION Unmanned aerial systems (UAS) have emerged as an important tool for state environmental agencies to quickly obtain data, more effectively respond to emergencies, and ensure worker safety while improving environmental results. UAS encompasses unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) (without a human pilot on board), commonly referred to as drones, as well as the person controlling the flight on the ground and a system of communications between the two. State environmental agencies have long been drivers of innovative approaches and programs to maximize environmental protection. ECOS has highlighted many examples through its annual State Program Innovation Awards, including modernized document management systems, new ways to interface with communities and share data, self-auditing programs, and more effective inspection and permitting programs. Use of UAS contributes to the continued evolution of state environmental agency approaches. This ECOS Green Report focuses on state environmental agency use of UAS,1 actual and potential benefits, and current and planned uses by the spotlighted state agencies. Each identified state environmental agency drone program is highlighted in more detail in the latter part of this report, including a summary of each state program along with benefits, current and planned activities, application highlights, lessons learned, state contacts, and links and resources. 1 In this report, the term “drone,” UAS, and UAV are used interchangeably or depending upon state preference. -

ATMOSPHERIC DIVING SUITS Kyznecov RR, Egorov IB

УДК 004.9 ATMOSPHERIC DIVING SUITS Kyznecov R.R., Egorov I.B., Scientific adviser: senior teacher Labusheva T.M. Siberian Federal University In our lives, information technology is found almost in everything - in smart stoves and in supercomputers. And atmospheric diving suits are not an exception. The report is dedicated to them. It will show the way they are connected to our future profession and what they can do. The most important periods of the atmospheric diving suit evolution are given below: LETHBRIDGE 1715 (UK) The first recorded attempt at protecting a diver in a rigid armor was done by John Lethbridge of Devonshire. It happened in England in 1715. The oak suit offered by him had a viewing port and holes for the diver’s arms. Water was kept out of the suit by greased leather cuffs which sealed around the operator’s arms. The device was said to have made many working dives to 60ft/18m. Lethbridge’s device probably performed as claimed. It is known from the painstaking work of Belgian expert, Robert Stenuit. Working under the protection of Comex with assistance from Comex’s founder, Henri Delauze, Stenuit imitated and operated as the "Lethbridge Engine," using only materials and techniques available in day time. JIM In 1960s an English company called DHB was interested very mush in Atmospheric Diving Suits. With the help of the government it started to perfect the Peress Tritonia suit from 1930 that it found out by coincidence and luck. After performing some tests with the old suit it became obvious that the joints had to be designed again.