Pouch Checking Guide How You Can Help Orphaned Australian Wildlife

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tammar Wallaby Macropus Eugenii (Desmarest, 1817)

Tammar Wallaby Macropus eugenii (Desmarest, 1817) Description Dark, grizzled grey-brown above, becoming rufous on the sides of the body and the limbs, especially in males. Pale grey-buff below. Other Common Names Dama Wallaby (South Australia) Distribution The Western Australian subspecies of the Tammar Wallaby was previously distributed throughout most of the south-west of Western Australia from Kalbarri National Park to Cape Arid on the south coast Photo: Babs & Bert Wells/DEC and extending to western parts of the Wheat belt. Size The Tammar Wallaby is currently known to inhabit three islands in the Houtman Abrolhos group (East and West Wallabi Island, and an introduced population on North Island), Garden Island near Perth, Kangaroo Island wallabies Middle and North Twin Peak Islands in the Archipelago of the Head and body length Recherche, and several sites on the mainland - including, Dryandra, Boyagin, Tutanning, Batalling (reintroduced), Perup, private property 590-680 mm in males near Pingelly, Jaloran Road timber reserve near Wagin, Hopetoun, 520-630 mm in females Stirling Range National Park, and Fitzgerald River National Park. The Tammar Wallaby remains relatively abundant at these sites which Tail length are subject to fox control. 380-450 mm in males They have been reintroduced to the Darling scarp near Dwellingup, 330-440 mm in females Julimar Forest near Bindoon, state forest east of Manjimup, Avon Valley National Park, Walyunga National Park, Nambung National Park and to Karakamia and Paruna Sanctuaries. Weight For further information regarding the distribution of this species Western Australian wallabies please refer to www.naturemap.dec.wa.gov.au 2.9-6.1 kg in males Habitat 2.3-4.3 kg in females Dense, low vegetation for daytime shelter and open grassy areas for feeding. -

Energetics and Biomechanics of Locomotion by Red Kangaroos (Macropus Rufus)

Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part B 120 (1998) 41–49 Review Energetics and biomechanics of locomotion by red kangaroos (Macropus rufus) Rodger Kram a,*, Terence J. Dawson b a Department of Integrati6e Biology, Uni6ersity of California, Berkeley CA 94720-3140, USA b School of Biological Sciences, Uni6ersity of New South Wales, Sydney NSW 2052, Australia Received 15 May 1997; received in revised form 22 September 1997; accepted 7 October 1997 Abstract As red kangaroos hop faster over level ground, their rate of oxygen consumption (indicating metabolic energy consumption) remains nearly the same. This phenomenon has been attributed to exceptional elastic energy storage and recovery via long compliant tendons in the legs. Alternatively, red kangaroos may have exceptionally efficient muscles. To estimate efficiency, we measured the metabolic cost of uphill hopping, where muscle fibers must perform mechanical work against gravity. We found that −1 uphill hopping was much more expensive than level hopping. The maximal rate of oxygen consumption measured (3 ml O2 kg s−1) exceeds all but a few vertebrate species. However, efficiency values were normal, 30%. At faster level hopping speeds the effective mechanical advantage of the extensor muscles of the ankle joint remained the same. Thus, kangaroos generate the same muscular force at all speeds but do so more rapidly at faster hopping speeds. This contradicts a recent hypothesis for what sets the cost of locomotion. The cost of transport (J kg−1 m−1) decreases at faster hopping speeds, yet red kangaroos prefer to use relatively slow speeds that avoid high levels of tendon stress. © 1998 Elsevier Science Inc. -

Platypus Collins, L.R

AUSTRALIAN MAMMALS BIOLOGY AND CAPTIVE MANAGEMENT Stephen Jackson © CSIRO 2003 All rights reserved. Except under the conditions described in the Australian Copyright Act 1968 and subsequent amendments, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, duplicating or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. Contact CSIRO PUBLISHING for all permission requests. National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Jackson, Stephen M. Australian mammals: Biology and captive management Bibliography. ISBN 0 643 06635 7. 1. Mammals – Australia. 2. Captive mammals. I. Title. 599.0994 Available from CSIRO PUBLISHING 150 Oxford Street (PO Box 1139) Collingwood VIC 3066 Australia Telephone: +61 3 9662 7666 Local call: 1300 788 000 (Australia only) Fax: +61 3 9662 7555 Email: [email protected] Web site: www.publish.csiro.au Cover photos courtesy Stephen Jackson, Esther Beaton and Nick Alexander Set in Minion and Optima Cover and text design by James Kelly Typeset by Desktop Concepts Pty Ltd Printed in Australia by Ligare REFERENCES reserved. Chapter 1 – Platypus Collins, L.R. (1973) Monotremes and Marsupials: A Reference for Zoological Institutions. Smithsonian Institution Press, rights Austin, M.A. (1997) A Practical Guide to the Successful Washington. All Handrearing of Tasmanian Marsupials. Regal Publications, Collins, G.H., Whittington, R.J. & Canfield, P.J. (1986) Melbourne. Theileria ornithorhynchi Mackerras, 1959 in the platypus, 2003. Beaven, M. (1997) Hand rearing of a juvenile platypus. Ornithorhynchus anatinus (Shaw). Journal of Wildlife Proceedings of the ASZK/ARAZPA Conference. 16–20 March. -

Post-Release Monitoring of Western Grey Kangaroos (Macropus Fuliginosus) Relocated from an Urban Development Site

animals Article Post-Release Monitoring of Western Grey Kangaroos (Macropus fuliginosus) Relocated from an Urban Development Site Mark Cowan 1,* , Mark Blythman 1, John Angus 1 and Lesley Gibson 2 1 Biodiversity and Conservation Science, Department of Biodiversity, Conservation and Attractions, Wildlife Research Centre, Woodvale, WA 6026, Australia; [email protected] (M.B.); [email protected] (J.A.) 2 Biodiversity and Conservation Science, Department of Biodiversity, Conservation and Attractions, Kensington, WA 6151, Australia; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +61-8-9405-5141 Received: 31 August 2020; Accepted: 5 October 2020; Published: 19 October 2020 Simple Summary: As a result of urban development, 122 western grey kangaroos (Macropus fuliginosus) were relocated from the outskirts of Perth, Western Australia, to a nearby forest. Tracking collars were fitted to 67 of the kangaroos to monitor survival rates and movement patterns over 12 months. Spotlighting and camera traps were used as a secondary monitoring technique particularly for those kangaroos without collars. The survival rate of kangaroos was poor, with an estimated 80% dying within the first month following relocation and only six collared kangaroos surviving for up to 12 months. This result implicates stress associated with the capture, handling, and transport of animals as the likely cause. The unexpected rapid rate of mortality emphasises the importance of minimising stress when undertaking animal relocations. Abstract: The expansion of urban areas and associated clearing of habitat can have severe consequences for native wildlife. One option for managing wildlife in these situations is to relocate them. -

Biparental Care and Obligate Monogamy in the Rock-Haunting Possum, Petropseudes Dahli, from Tropical Australia

ANIMAL BEHAVIOUR, 2000, 59, 1001–1008 doi:10.1006/anbe.1999.1392, available online at http://www.idealibrary.com on Biparental care and obligate monogamy in the rock-haunting possum, Petropseudes dahli, from tropical Australia MYFANWY J. RUNCIE CRC for Sustainable Development of Tropical Savannas, Northern Territory University (Received 10 May 1999; initial acceptance 9 June 1999; final acceptance 30 December 1999; MS. number: 6222R) Monogamy is rare among mammals, including marsupials. I studied the social organization of the little-known rock-haunting possum in Kakadu National Park in Northern Australia. Preliminary field observations revealed that the majority of possums live in cohesive groups consisting of a female–male pair and young, suggesting a monogamous mating system. I used radiotracking to determine home range patterns, and observations to measure the degree of symmetry between the sexes in maintaining the pair bond and initiating changes in group activity. I also measured the extent of maternal and paternal indirect and direct care. Nocturnal observations and radiotelemetric data from 3 years showed that six possum groups maintained nonoverlapping home ranges with long-term consorts and young sharing dens. Males contributed more than females to maintaining the pair bond but they contributed equally to parental care. For the first time, the parental behaviours of bridge formation, embracing, marshalling of young, sentinel behaviour and tail beating are reported in a marsupial. Males participated to a high degree in maintaining relationships with one mate and their offspring. Collectively, these results suggest that the mating system of this wild population of rock-haunting possums is obligate social monogamy. -

Thylacinidae

FAUNA of AUSTRALIA 20. THYLACINIDAE JOAN M. DIXON 1 Thylacine–Thylacinus cynocephalus [F. Knight/ANPWS] 20. THYLACINIDAE DEFINITION AND GENERAL DESCRIPTION The single member of the family Thylacinidae, Thylacinus cynocephalus, known as the Thylacine, Tasmanian Tiger or Wolf, is a large carnivorous marsupial (Fig. 20.1). Generally sandy yellow in colour, it has 15 to 20 distinct transverse dark stripes across the back from shoulders to tail. While the large head is reminiscent of the dog and wolf, the tail is long and characteristically stiff and the legs are relatively short. Body hair is dense, short and soft, up to 15 mm in length. Body proportions are similar to those of the Tasmanian Devil, Sarcophilus harrisii, the Eastern Quoll, Dasyurus viverrinus and the Tiger Quoll, Dasyurus maculatus. The Thylacine is digitigrade. There are five digital pads on the forefoot and four on the hind foot. Figure 20.1 Thylacine, side view of the whole animal. (© ABRS)[D. Kirshner] The face is fox-like in young animals, wolf- or dog-like in adults. Hairs on the cheeks, above the eyes and base of the ears are whitish-brown. Facial vibrissae are relatively shorter, finer and fewer than in Tasmanian Devils and Quolls. The short ears are about 80 mm long, erect, rounded and covered with short fur. Sexual dimorphism occurs, adult males being larger on average. Jaws are long and powerful and the teeth number 46. In the vertebral column there are only two sacrals instead of the usual three and from 23 to 25 caudal vertebrae rather than 20 to 21. -

Dipodomys Ingens)

Species Status Assessment Report for the Giant Kangaroo Rat (Dipodomys ingens) Photo by Elizabeth Bainbridge Version 1.0 August 2020 Prepared by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service August 2020 GKR SSA Report – August 2020 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service listed the giant kangaroo rat (Dipodomys ingens) as endangered under the Endangered Species Act in 1987 due to the threats of habitat loss and widespread rodenticide use (Service 1987, entire). The giant kangaroo rat is the largest species in the genus that contains all kangaroo rats. The giant kangaroo rat is found only in south-central California, on the western slopes of the San Joaquin Valley, the Carrizo and Elkhorn Plains, and the Cuyama Valley. The preferred habitat of the giant kangaroo rat is native, sloping annual grasslands with sparse vegetation (Grinnell, 1932; Williams, 1980). This report summarizes the results of a species status assessment (SSA) that the U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service (Service) completed for the giant kangaroo rat. To assess the species’ viability, we used the three conservation biology principles of resiliency, redundancy, and representation (together, the 3Rs). These principles rely on assessing the species at an individual, population, and species level to determine whether the species can persist into the future and avoid extinction by having multiple resilient populations distributed widely across its range. Giant kangaroo rats remain in fragmented habitat patches throughout their historical range. However, some areas where giant kangaroo rats once existed have not had documented occurrences for 30 years or more. The giant kangaroo rat is found in six geographic areas (units), representing the northern, middle, and southern portions of the range. -

Exotic to Australia

Fact sheet Introductory statement Foot and mouth disease (FMD) is a highly contagious viral vesicular disease of cloven hoofed animals. It is a major issue in international trade in livestock and livestock products. Australia is free of the disease and it is vital that it remains so. The 2001 outbreak in the United Kingdom resulted in over 10 million cattle and sheep being slaughtered at a cost of over GBP 8 billion in order to eradicate the disease. This fact sheet summarises what is known about FMD and Australian native wildlife. WHA also manages an fact sheet that briefly summarises information on FMD and feral animals “Foot and Mouth Disease (General Information)”. Aetiology and natural hosts FMD is caused by an aphthovirus belonging to the family Picornaviridae. It is a single stranded non enveloped 25 nm RNA virus. There are seven serotypes: A, O, C, SAT 1, SAT 2, SAT 3, and Asia 1. All cloven hoofed animals are considered susceptible. Cases have also been reported in elephants, hedgehogs and some rodents. World distribution and occurrences in Australia FMD is endemic in Africa, the Middle East, Asia and parts of South America. The disease has almost been eradicated from Europe with the most recent cases occurring in the United Kingdom and Cyprus in 2007. FMD has not occurred in Australia for over 130 years, and then only in livestock. Minor outbreaks occurred in 1801, 1804, 1871 and 1872 (Geering et al 1995). However, a case was reported in an eastern grey kangaroo (Macropus giganteus) held in a zoo in India (Bhattacharya et al 2003). -

The Kangaroo Island Tammar Wallaby

The Kangaroo Island Tammar Wallaby Assessing ecologically sustainable commercial harvesting A report for the Rural Industries Research and Development Corporation by Margaret Wright and Phillip Stott University of Adelaide March 1999 RIRDC Publication No 98/114 RIRDC Project No. UA-40A © 1999 Rural Industries Research and Development Corporation. All rights reserved. ISBN 0 642 57879 6 ISSN 1440-6845 "The Kangaroo Island Tammar Wallaby - Assessing ecologically sustainable commercial harvesting " Publication No: 98/114 Project No: UA-40A The views expressed and the conclusions reached in this publication are those of the author and not necessarily those of persons consulted. RIRDC shall not be responsible in any way whatsoever to any person who relies in whole or in part on the contents of this report. This publication is copyright. However, RIRDC encourages wide dissemination of its research, providing the Corporation is clearly acknowledged. For any other enquiries concerning reproduction, contact the Publications Manager on phone 02 6272 3186. Researcher Contact Details Margaret Wright & Philip Stott Department of Environmental Science and Management University of Adelaide ROSEWORTHY SA 5371 Phone: 08 8303 7838 Fax: 08 8303 7956 Email: [email protected] [email protected] Website: http://www.roseworthy.adelaide.edu.au/ESM/ RIRDC Contact Details Rural Industries Research and Development Corporation Level 1, AMA House 42 Macquarie Street BARTON ACT 2600 PO Box 4776 KINGSTON ACT 2604 Phone: 02 6272 4539 Fax: 02 6272 5877 Email: [email protected] Website: http://www.rirdc.gov.au Published in March 1999 Printed on environmentally friendly paper by Canprint ii Foreword The Tammar Wallaby on Kangaroo Island, South Australia, is currently managed as a vertebrate pest. -

Eastern Grey Kangaroo Macropus Giganteus Shaw 1790 As a Vulnerable Species in Part 1 of Schedule 2 of the Act

NSW SCIENTIFIC COMMITTEE Preliminary Determination The Scientific Committee, established by the Threatened Species Conservation Act, has made a Preliminary Determination NOT to support a proposal to list the Eastern Grey Kangaroo Macropus giganteus Shaw 1790 as a Vulnerable species in Part 1 of Schedule 2 of the Act. Rejection of nominations is provided for by Part 2 of the Act. The Scientific Committee has found that: 1. Macropus giganteus Shaw 1790 (family Macropodidae), known as the Eastern Grey Kangaroo, is a large, highly sexually dimorphic macropod. Head-body to 2302 mm (males), 1857 mm (females); tail to 1090 mm (males), 842 mm (females); weight to 85 kg (males), 42 kg (females). Grey-brown dorsally, paler ventrally and on legs. Ears long, dark brown outside, pale grey inside with whitish fringe. Distal third of tail blackish. Muzzle finely haired (Menkhorst and Knight 2001; Johnson 2006; Coulson 2008). 2. Macropus giganteus is endemic to Australia. It is widely distributed in eastern Australia from Cape York Peninsula, Queensland, to far southeast South Australia and northeastern Tasmania. It is found throughout New South Wales (NSW). In western NSW, northwestern Victoria and southwestern Queensland M. giganteus is sympatric with its sister species the Western Grey Kangaroo (Macropus fuliginosus) (Johnson 2006; Coulson 2008). Eastern and Western Grey Kangaroos were recognised as separate species only in the 1970s (Kirsch and Poole 1972). Macropus giganteus mostly occurs where annual rainfall is >250 mm (Caughley et al. 1987b) in sclerophyll forest, woodland (including mallee), shrubland and heathland. It can also occur in modified habitats including farmland with remnant native vegetation, pine plantations and golf courses (Menkhorst and Knight 2001; Johnson 2006; Coulson 2008; Dawson 2012). -

Meet a Marsupial

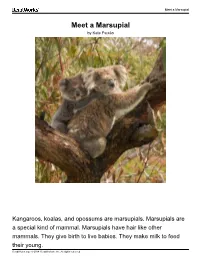

Meet a Marsupial Meet a Marsupial by Kate Paixão Kangaroos, koalas, and opossums are marsupials. Marsupials are a special kind of mammal. Marsupials have hair like other mammals. They give birth to live babies. They make milk to feed their young. ReadWorks.org · © 2014 ReadWorks®, Inc. All rights reserved. Meet a Marsupial But marsupials have something that makes them different from other mammals. Female marsupials have a pouch. They use this pouch to carry their babies. Marsupial babies are called joeys. A joey stays in its mother's pouch for a long time. When it is old enough, the joey gets out and can move around on its own! ReadWorks.org · © 2014 ReadWorks®, Inc. All rights reserved. ReadWorks Vocabulary - mammal mammal mam·mal Definition noun 1. an animal that has hair and feeds its babies with milk from the mother. Dogs, whales, and humans are mammals. Spanish cognate mamífero: The Spanish word mamífero means mammal. These are some examples of how the word or forms of the word are used: 1. Bats are mammals. Mammals are warm-blooded animals that have hair on their bodies. 2. Whales are big ocean mammals. Mammals are animals that drink milk from their mothers. 3. The African elephant is the largest living land mammal, and the ostrich is the largest living bird. 4. The only fish Liza liked were dolphins, except her teacher told her that dolphins were mammals, not fish. 5. Every dog is a mammal. All mammals have hair on their bodies. People, horses, and elephants are also mammals. 6. The Mississippi is home to all kinds of animals. -

Cercartetus Lepidus (Diprotodontia: Burramyidae)

MAMMALIAN SPECIES 842:1–8 Cercartetus lepidus (Diprotodontia: Burramyidae) JAMIE M. HARRIS School of Environmental Science and Management, Southern Cross University, Lismore, New South Wales, 2480, Australia; [email protected] Abstract: Cercartetus lepidus (Thomas, 1888) is a burramyid commonly called the little pygmy-possum. It is 1 of 4 species in the genus Cercartetus, which together with Burramys parvus form the marsupial family Burramyidae. This Lilliputian possum has a disjunct distribution, occurring on mainland Australia, Kangaroo Island, and in Tasmania. Mallee and heath communities are occupied in Victoria and South Australia, but in Tasmania it is found mainly in dry and wet sclerophyll forests. It is known from at least 18 fossil sites and the distribution of these reveal a significant contraction in geographic range since the late Pleistocene. Currently, this species is not listed as threatened in any state jurisdictions in Australia, but monitoring is required in order to more accurately define its conservation status. DOI: 10.1644/842.1. Key words: Australia, burramyid, hibernator, little pygmy-possum, pygmy-possum, Tasmania, Victoria mallee Published 25 September 2009 by the American Society of Mammalogists Synonymy completed 2 April 2008 www.mammalogy.org Cercartetus lepidus (Thomas, 1888) Little Pygmy-possum Dromicia lepida Thomas, 1888:142. Type locality ‘‘Tasma- nia.’’ E[udromicia](Dromiciola) lepida: Matschie, 1916:260. Name combination. Eudromicia lepida Iredale and Troughton, 1934:23. Type locality ‘‘Tasmania.’’ Cercartetus lepidus: Wakefield, 1963:99. First use of current name combination. CONTEXT AND CONTENT. Order Diprotodontia, suborder Phalangiformes, superfamily Phalangeroidea, family Burra- myidae (Kirsch 1968). No subspecies for Cercartetus lepidus are currently recognized.