Cot LWRP DRAFT Desktop.Pub

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Historic Overview

Updated Reconnaissance Level Survey of Historic Resources Town of Amherst HISTORIC OVERVIEW LOCATION The Town of Amherst lies in northern Erie County, New York. It is bordered by Niagara County to the north, the Erie County towns of Clarence to the east, Cheektowaga to the south, and Tonawanda to the west. The total area of Amherst is approximately 53 square miles. ENVIRONMENTAL SETTING The natural environmental setting influenced prehistoric and historic settlement patterns in the Town of Amherst. The town lies within the Erie‐Ontario Lake Plain physiographic province, described as a nearly level lowland plain with few prominent topographic features. The area is underlain by Onondaga limestone dating to the Late Devonian period. Later glaciations shaped much of the western New York topography, including that of Amherst. One of the most prominent topographic features in the relatively featureless province is the Onondaga Escarpment, an east‐west trending hard limestone bedrock formation that lies in the southern portion of the Town of Amherst. The Onondaga Escarpment proved resistant to the effects of glacial scouring and it forms the southern boundary of a large basin once occupied by the shallow glacial Lake Tonawanda. Lake Tonawanda eventually receded leaving behind wetlands and deposits of clay and sand throughout much of northern Amherst (Owens et al. 1986:2). The most important drainages in the Town of Amherst are Tonawanda Creek, Ransom Creek, and Ellicott Creek. Tonawanda Creek forms the northern boundary between Amherst and Niagara County. It flows in a western direction and drains much of the eastern and Northern portions of Amherst. -

Impact of Urbanization on Large Wood Sizes and Associated Recruitment Zones

hydrology Article Impact of Urbanization on Large Wood Sizes and Associated Recruitment Zones Matthew T. Allen 1 and Philippe G. Vidon 2,* 1 Atlantic States Rural Water & Wastewater Association, 11 High St., Suite 204, Suffield, CT 06078, USA; [email protected] 2 Department of Sustainable Resources Management, State University of New York College of Environmental Science and Forestry (SUNY-ESF), 1 Forestry Drive, Syracuse, NY 13210, USA * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 14 October 2020; Accepted: 13 November 2020; Published: 16 November 2020 Abstract: Although the presence of large wood (LW) has long been recognized to enhance watershed function, land use impact on LW remains poorly understood. Using a series of six watersheds, we investigate the relationships between LW recruitment zones, LW size, and LW jam occurrence and land use. Although the results in general show urban land use to severely limit LW, they also stress that agricultural land use may be positively correlated to LW. Occurrence of potentially productive LW recruitment zones is nevertheless best correlated to total forest land cover and forested riparian area. However, the lack of mature forest due to previous widespread deforestation linked to historical agricultural land use is likely a limiting legacy effect. Since the pattern of land use seen in the study area is typical of much of the developed world, our results suggest the limiting of LW may be a major way in which watersheds are impacted in many regions. Accordingly, reintroduction of LW represents a significant opportunity to restore watersheds on a broad scale. Specifically, we propose a mix of passive conservation and active restoration of LW sources and that the targeting of these tactics be planned using the spatial analysis methods of this study. -

Ellicott Creek Park Final Plan

2.4 ELLICOTT CREEK PARK FINAL PLAN ELLICOTT CREEK PARK DESCRIPTION At 165 acres, Ellicott Creek Park is one of the original Heritage parks in the County system, and is entirely within an urban environment setting. The park is centrally located and easily accessed by residents of Tonawanda, Amherst, Buffalo, and North Tonawanda (Niagara County), and is also a destination along area bike routes, including the Ellicott Creek Bike Path (via the Town of Amherst), and Erie Canalway Trail which connects with the Shoreline Trail. It is one of the four oldest parks in the system, acquired by the County in 1925 due to its attractive landscape setting between Ellicott Creek and the Erie Canal (Tonawanda Creek). This beautiful Heritage park is noted for its impressive collection of old stone structures and waterfront setting. Ellicott Creek Park is generally flat, which was considered ideal for the development of many field sports and active recreation, such as tennis and ice- skating. The Park is bisected by a major floodway corridor (spillway flume) between the two Creeks. Park Location Map: Ellicott Creek Park is located in the Town of Tonawanda PARK SPECIFIC PRIORITIES • Preserve and enhance Heritage areas and special park features, including; Repoint/clean stonework where needed, replace missing stones, replace or repair roofs, make improvements to concrete/asphalt floors, etc. to all historic structures and facilities. • Reduce lawn mowing in passive recreational areas, provide meadows and wildflowers to enhance natural character of park. • Coordinate with Friends of Ellicott Island Bark Park to maintain and upgrade amenities on Ellicott Island, as well as protecting and enhancing sensitive shoreline conditions. -

NIAGARA RIVER WATERSHED MANAGEMENT PLAN (Phase 1)

ATLAS NIAGARA RIVER WATERSHED MANAGEMENT PLAN (Phase 1) September 2013 During the development of the Niagara River Watershed Management Plan (Phase 1), an impressive collection of existing plans, studies, reports, data, information and maps were gathered and reviewed to help establish the overall physical, biological and ecological conditions of the Niagara River Watershed. This Atlas is a full assembly of these resources, providing a comprehensive record of previous watershed efforts utilized in the watershed management planning process. NIAGARA RIVER WATERSHED MANAGEMENT PLAN Developed By: 1250 Niagara Street Buffalo, NY 14213 Buffalo Niagara RIVERKEEPER® is a community‐based organization dedicated to protecting the quality and quantity of water, while connecting people to water. We do this by cleaning up pollution from our waterways, restoring fish and wildlife habitat, and enhancing public access through greenways that expand parks and open space. In Conjunction with: 2919 Delaware Ave. 478 Main Street Kenmore, NY 14217 Buffalo, NY 14202 Financial support for the development of this Atlas and the Niagara River Watershed Management Plan (Phase 1) is from the New York State Department of State with funds provided under Title 11 of the Environmental Protection Fund. For more information on the Niagara River Watershed Management Plan (Phase 1), or to become involved in our regional watershed’s protection and restoration, visit Buffalo Niagara RIVERKEEPER® online at www.bnriverkeeper.org. For more information regarding watershed planning in New York State, visit the NYS Department of State’s website at www.nyswaterfronts.com/watershed_home.asp. 1 NIAGARA RIVER WATERSHED MANAGEMENT PLAN 2 NIAGARA RIVER WATERSHED MANAGEMENT PLAN Atlas Layout The Atlas has been divided into the following sections that correspond with the watershed as a whole and the 11 sub-watersheds that make up the Niagara River watershed. -

Water Quality

NIAGARA RIVER WATERSHED MANAGEMENT PLAN (Phase I) Chapter 4: Water Quality More than 1 billion people in Clean water is an essential human need and one whose the world do not have access to value will increase as global climates change. The safe drinking water, yet we are Niagara River Watershed and Lake Erie’s tremendous privileged to have 20 percent water supply supports everything from daily living needs of the world’s accessible fresh (drinking, bathing, cooking) to recreation (swimming, water at our front door. fishing, boating) and local economies (industry, tourism, shipping). Presently, the Great Lakes provide drinking water to 34 million people in the United States and Canada, and support more than 1.5 million U.S. jobs that generate $62 billion in wages1. While certain areas of the watershed have improved considerably since the enactment of the Clean Water Act in 1972 (i.e. Buffalo River), there are a number of areas within the watershed with poor and impacted water quality stemming from various types of pollution, existing storm-water management practices, adverse land uses and development trends, and other stressors that threaten our freshwater resources. Water Classification & Quality Assessment There are several mechanisms by which water quality is evaluated in New York State. One of the primary methods includes classifying water resources based upon their best uses and determining whether or not the water quality is in line with those uses2. For example, a water body used for drinking water has lower thresholds for contaminants or pollutants than a water body used solely for recreation. -

Description of the Niagara Quadrangle

DESCRIPTION OF THE NIAGARA QUADRANGLE. By E. M. Kindle and F. B. Taylor.a INTRODUCTION. different altitudes, but as a whole it is distinctly higher than by broad valleys opening northwestward. Across northwestern GENERAL RELATIONS. the surrounding areas and is in general bounded by well-marked Pennsylvania and southwestern New York it is abrupt and escarpments. i nearly straight and its crest is about 1000 feet higher than, and The Niagara quadrangle lies between parallels 43° and 43° In the region of the lower Great Lakes the Glaciated Plains 4 or 5 miles back from the narrow plain bordering Lake Erie. 30' and meridians 78° 30' and 79° and includes the Wilson, province is divided into the Erie, Huron, and Ontario plains From Cattaraugus Creek eastward the scarp is rather less Olcott, Tonawanda, and Lockport 15-minute quadrangles. It and the Laurentian Plateau. (See fig. 2.) The Erie plain abrupt, though higher, and is broken by deep, narrow valleys thus covers one-fourth of a square degree of the earth's sur extending well back into the plateau, so that it appears as a line face, an area, in that latitude, of 870.9 square miles, of which of northward-facing steep-sided promontories jutting out into approximately the northern third, or about 293 square miles, the Erie plain. East of Auburn it merges into the Onondaga lies in Lake Ontario. The map of the Niagara quadrangle shows escarpment. also along its west side a strip from 3 to 6 miles wide comprising The Erie plain extends along the base of the Portage escarp Niagara River and a small area in Canada. -

New York's Upper Tonawanda Creek Section 319 Success Story

Section 319 NONPOINT SOURCE PROGRAM SUCCESS STORY Implementing Agricultural BestNew Management Practices York Restores Upper Tonawanda Creek Nutrients and sediment in runoff from agricultural activities and Waterbody Improved other nonpoint sources impaired the water supply use for the upper portion of Tonawanda Creek in Wyoming and Genesee counties in New York. As a result, the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation (NYSDEC) included this segment on the New York State Priority Waterbodies List in 1996 and added it to the Clean Water Act (CWA) section 303(d) list of impaired waters in 2004 for silt and sediment. The soil and water conservation districts (SWCDs) in both counties worked with farmers to install agricultural best management practices (BMPs) to reduce sediment and nutrient pollutant loads in the watershed. The upper portion of Tonawanda Creek now meets water quality standards for total dissolved solids, prompting NYSDEC to remove it from New York’s list of impaired waters in 2012. Problem Upper Tonawanda Creek Watersrshedd New York’s Tonawanda Creek is a 101-mile-long tributary to the Niagara River. The creek drains approximately 631.9 square miles, making its water- shed one of the largest in western New York. The watershed drains portions of Wyoming, Genesee, Niagara and Erie counties, as well as the Tonawanda native reservation area. The principal land use in the watershed is agriculture (45 percent; primarily dairy, vegetable crops and cash crops), followed by forest (27 percent), urban/residential (17 percent) and wetlands (11 percent). Tonawanda Creek flows through the former lake bed of the prehistoric Glacial Lake Tonawanda, and many of the wetlands in the watershed are remnants of that earlier time. -

Bridge Data: August 31, 2021

NY State Highway Bridge Data: August 31, 2021 Erie County Year Date BIN Built or of Last Poor Region County Municipality Location Feature Carried Feature Crossed Owner Replaced Inspectio Status n 05 Erie Akron (Village) 1034780 2.1 MI N JCT RTS 5 + 93 93 93 53021046 MURDER CREEK NYSDOT 1932 04/13/2020 N 05 Erie Akron (Village) 1034790 0.2 MI S JCT RTS 93 + 267 93 93 53021056 MURDER CREEK NYSDOT 1961 04/13/2020 N 05 Erie Akron (Village) 3362100 IN AKRON FALLS COUNTY PRK AKRON PK SERV RD MURDER CREEK 30 - County 2013 11/27/2019 N 05 Erie Akron (Village) 3326450 SE CORNER OF AKRON AKRON-CRITTENDEN MURDER CREEK 30 - County 1958 05/05/2020 Y 05 Erie Akron (Village) 3362090 1.4 MI N JCT SH 5 & SH 93 BROOKLYN STREET MURDER CREEK 30 - County 1957 07/08/2020 N 05 Erie Akron (Village) 3326350 IN AKRON FALLS PARK PARKVIEW DRIVE MURDER CREEK 30 - County 1933 09/04/2020 N 05 Erie Akron (Village) 3328800 1.5 MI NE JCT 93'5 STATE STREET MURDER CREEK 41 - Village 1938 09/03/2020 Y 05 Erie Alden (Town) 1022930 7.4 MI E JCT SH 33 & SH78 33 33 53012128 ELLICOTT CREEK NYSDOT 1960 08/13/2020 Y 05 Erie Alden (Town) 3326990 4.6 MI WSW JCT RTE 33& CL 952Q952Q53011129 ELLICOTT CREEK NYSDOT 1991 08/13/2019 N 05 Erie Alden (Town) 3362520 .2 MI S JCT SH 33 & CR 1 ALDEN CRTTNDEN RD CSX TRANS/ AMTRAK 30 - County 1990 11/12/2020 N 05 Erie Alden (Town) 3326850 1 MILE NORTH OF ALDEN ALDEN-CRITTENDEN ELLICOTT CREEK 30 - County 1964 07/13/2020 N 05 Erie Alden (Town) 5523520 .9 MI SE OF MILL GROVE CREEKVIEW DRIVE ELLICOTT CREEK 20 - State - Other 1991 07/21/2021 N 05 Erie -

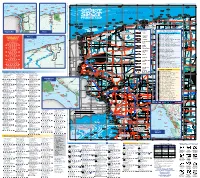

FAB Fishing Guide Side 1.Pdf

15 0 60 79°5'0"W 79°0'0"W 78°55'0"W 78°50'0"W 78°45'0"W 78°40'0"W 78°35'0"W 78°30'0"W 3 360 0 345 36 N 360 " N " 0 45 ' 0 ' 30 5 5 2 ° 2 ° 3 30 3 3 4 345 4 30 300 e e 270 v Av A Western ke k r Four Mile 30 La 240 Creek 3 Pa 15 Lake Rd New York State Park Keg Ck HOT 210 Rd 30 Lake 80 «¬18F 3 ke Rd 1 St E La 10 9 4 ntario St 15 Bluff O Main Lake Ontario 50 W 1 Fort Niagara 120 5 t 45 State 2 S Park 00 s 3 0 10 Rd Krull 9 d Rd ht Rd ke Golden Hill e R ort La d shor kp ig ke SP T See inset: ke oc State Park La 60 t L La County 1 W me S He 60 L na e rd o Park k 1 c Un Olcott a 93 0 k Wa 3 ¬ d L St « port p k FISHING MAP R ck o h C Lo 5 Fis 6 r 1 r t 70 e O Jockey Rd 2 k St a l c NOT FOR NAVIGATION USE u in C d hu o F ish Creek Q r R t Lak ch t e Rd Ma Veterans St r Roosevelt Hwy R e 2S4w0igert Rd Park d 2 W k om C Godfrey Rd e g o K 18 C ¬ d 25 Ck « C 2 k ill R n H 4 e B Rd N d r l l ld o a " 5 3 Somerset G N i e 0 r d 21 4 " v O 0 il ' Krull l m e R Town Park 0 ' R 0 o R County 0 d 2 Keg Creek d 5 ° 19 2 o 2 Co Ck Park d ° NEWFANE 3 b R 5 R k 6 3 4 1 e d C s 135 105 R 4 e r l ke W Somerset Rd e i a t lip W L l n Rd ma n d Cole d i Millers R M m hi R r L 18 o P u it «¬ Balmer Rd y s o t e F ns 5 n s a 6 u o Tr P Eighteen Mile d C a d See inset: 5 R r R k Wilson s r 30 w s e l Tuscarora e k a 3 Wilson Creek ul Wilson Burt Rd y C State Park H Marsh F k S 15 4 C d E ile Town Line Rd R Wilson Burt Rd B 7 H M r 8 r 2 o e a Drake Settlement Rd 1 148 k p 269 v n «¬ C i ¬ k « c See inset: 15 7 o i 5 R FISH KEY h 1 d n SHORE FISHING SITES Joseph s -

2.0 Historic Overview

Intensive Level Historic Resources Survey of Selected Resources Town of Amherst 2.0 HISTORIC OVERVIEW CBCA PN 16-049 2 - 1 © September 2017 Intensive Level Historic Resources Survey of Selected Resources Town of Amherst 2.0 HISTORIC OVERVIEW Location The Town of Amherst is located in Western New York State in the northern section of Erie County. To the north, Tonawanda Creek divides the town from Niagara County. The Town of Clarence is at its eastern border, with Transit Road as the dividing line. Amherst is set off from the Town of Cheektowaga, to the south, by Wehrle Drive and the NYS Thruway, I-90. At its western border, Niagara Falls Boulevard separates Amherst from the Town of Tonawanda; and the city of Buffalo borders it to the southwest near Main Street and Kenmore Avenue at Grover Cleveland Park. Amherst is 53.28 square miles or 33,600 acres and has a population (as of July 1, 2017) of 124,733.1 Setting and Geography Geography played an important role in the development of the Town of Amherst. Settlers were attracted by rich soil and timber resources and the water power of the creeks. Mills along the creeks were important to the farm economy of Amherst during the nineteenth century. Ellicott Creek, once called Eleven-Mile Creek, enters the town south of the Village of Williamsville and flows northwest, emptying into Tonawanda Creek not far from the Niagara River. Tonawanda Creek on the town’s northern border flows west to the Niagara River and eventually became part of New York’s Erie Canalway system. -

Water Resources of the Iroquois National Wildlife Refuge, Genesee and Orleans Counties, New York, 2009–2010

Prepared in cooperation with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Water Resources of the Iroquois National Wildlife Refuge, Genesee and Orleans Counties, New York, 2009–2010 Scientific Investigations Report 2012–5027 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Cover. All photos from the Iroquois National Wildlife Refuge photo archives. Upper Left - Cayuga Marsh overlook at NY-Route 77, autumn scene. Right - Ice fog (hoar frost) view of wetland behind Iroquois Refuge office building along Casey Road, midwinter. Lower left - Oak Orchard Creek looking downstream from Knowlesville Road, on the eastern side of the Refuge, early autumn. Water Resources of the Iroquois National Wildlife Refuge, Genesee and Orleans Counties, New York, 2009–2010 By William M. Kappel and Matthew B. Jennings Prepared in cooperation with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Scientific Investigations Report 2012–5027 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior KEN SALAZAR, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey Marcia K. McNutt, Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2012 For more information on the USGS—the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment, visit http://www.usgs.gov or call 1–888–ASK–USGS. For an overview of USGS information products, including maps, imagery, and publications, visit http://www.usgs.gov/pubprod To order this and other USGS information products, visit http://store.usgs.gov Any use of trade, product, or firm names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. -

Water Resources of the Buffalo- Niagara Falls Region

GEOLOGICAL SURVEY CIRCULAR 173 WATER RESOURCES OF THE BUFFALO NIAGARA FALLS REGION By Charles W. Reck, and Edward T. Simmons UNITEb STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Oscar L. Chapman, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY W. E. Wrather, Director GEOLOGICAL SURVEY CffiCULAR 173 WATER RESOURCES OF THE BUFFALO-NIAGARA FALLS REGION By Charles W. Reck, and Edward T. Simmons Based on data collected in cooperation with the New York Department of Public Works, New York Department of Conservation, New York Power and Control Commission, and Corps. of Engineers Washington, D. C., 1952 Free on application to the Geological Survey, Washington 25, D. C. CONTENTS Page Page Introduction ............................................. 1 Ground water-Continued The Niagara Frontier ............................ .. 1 Quality of water ................................... .. 21 Topography .......................................... 1 Pollution ............................................. 21 Climate ............................................... 1 Temperature ....................................... 23 Population and industry ......................... .. 2 Public water supplies .............................. .. 23 Natural resources ... : .............................. 4 City of Buffalo .. - .................................. 23 Sources of water ....................................... 4 City of Niagara Falls ............................ 24 Surface water .......................................... 4 Western New York Water Co .................. 24 Lake Erie: .........................................