University of Florida Thesis Or Dissertation Formatting

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Survival of the the Fittest? the Rebranding of WV Higher Education

SURVIVAL OF THE FITTEST? THE REBRANDING OF WEST VIRGINIA HIGHER EDUCATION EXCERPT: CHAPTER ONE: REBRANDING -- AN INTRODUCTION James Martin Owston, EdD Marshall University College of Education and Human Services Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Marshall University Graduate College in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Education in Educational Leadership Committee Chair, Barbara L. Nicholson, PhD Powell E. Toth, PhD H. Keith Spears, EdD Charles H. Polk, EdD Huntington, West Virginia, 2007 Keywords: Higher education, rebranding, brand identity, college-to-university Copyright 2007 by James Martin Owston SURVIVAL OF THE FITTEST? THE REBRANDING OF WEST VIRGINIA HIGHER EDUCATION CHAPTER ONE: REBRANDING -- AN INTRODUCTION We do what we must, and call it by the best names. – Ralph Waldo Emerson (n.d.). Your premium brand had better be delivering something special, or it's not going to get the business – Warren Buffet (n.d.). In an April 2006 editorial, New York Times columnist Stephan Budiansky recounted his research for a satirical novel set on the campus of a university. “The idea was to have a bunch of gags about how colleges prostitute themselves to improve their U.S. News & World Reports’ rankings and keep up a healthy supply of tuition-paying students while wrapping their craven commercialism in high-minded sounding academic blather.” Budiansky continued, “One of my best bits, or so I thought, was about how the fictional university . had hired a branding consultant to come up with a new name with the hip, possibility-rich freshness needed to appeal to today’s students. Two weeks later, a friend called to say it was on the front page of The Times: ‘To Woo Students, Colleges Choose Names That Sell’” (p. -

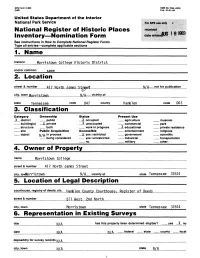

Nomination Form See Instructions in How to Complete National Register Forms Type All Entries—Complete Applicable Sections______1

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 Exp. 10-31-84 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Inventory—Nomination Form See instructions in How to Complete National Register Forms Type all entries—complete applicable sections________________ 1. Name historic Morris town College Historic District and/or common same 2. Location street & number 417 North James N/ not for publication city, town Morristown N/A — vicinity of state Tennessee code 047 county Hambl en code 063 3. Classification Category Ownership Status Present Use X district public _ X_ occupied agriculture museum building(s) _ X- private _ X_ unoccupied commercial park structure both work in progress _ X_ educational private residence site Public Acquisition Accessible entertainment religious object N/A- in Process _ X- yes: restricted government scientific being considered yes: unrestricted industrial transportation no military other: 4. Owner of Property name Morristown College street & number 417 North James Street city, towMorris town N/A_ vicinity of state Tennessee 37814 5. Location of Legal Description courthouse, registry of deeds, etc. Hamblen County Courthouse, Register of Deeds street & number____________511 West 2nd North________ city, town Morristown state Tennessee 37814 6. Representation in Existing Surveys title has this property been determined eligible? date _N/A, federal __ state __ county __ local depository for survey records [\j//\ city, town state N/A 7. Description Condition Check one Check one excellent deteriorated unaltered _ X original site _J(_good ruins X altered moved date fair unexposed Describe the present and original (iff known) physical appearance The Morristown College Historic District is located in Morristown, Tennessee (pop. -

The Bennett Banner

ARCHIVES Bennett Colloga G/^eensb'ofo, II c . “Living Christmas Madonnas” THE BENNETT< BANNER Dec, 7— 7 p. m. “Believing that an informed campus is a Key to Democracy’’ VOL. XXVI, NO. Ill GREENSBORO, NORTH CAROLINA NOVEMBER, 1958 Morehouse Sives Ten Girls Elected Itnnual Concert To College Highlighting the annual More Who's Who house College Glee Club visit Ten Bennett students—nine sen was the combined singing of the iors and one junior—have been Morehouse Glee Club and the Ben selected to “Who’s Who Among nett Choir in three musical com Students in American Colleges and positions. Universities” for the academic The selections were “In the year 1958-59. Year That King Uzziah Died,” ar These seniors so honored are: ranged by David McK. Williams; “Rejoice In the Lamb,” a festival Hudene Abney of Norristown, cantata, with music by Benjamin Pennsylvania, a pre-law student Britten; and “Alleluia,” by Randall who is spending her senior year Thompson. tudying at the American Univer These outstanding works were sity, Washington, D. C., under one sung first on Friday, November of Bennett’s cooperative programs. 28, during the chapel period. The Barbara Campbell of Greens concert was held Friday night boro, North Carolina, English at 8 o’clock in the Annie Merner major, editor of the Bennett Ban Pfeiffer Chapel. ner, and a member of Alpha Kap The combined singing of the two pa Mu Honor Siciety. choral groups, as well as the con Jamesena Chalmers of Fayette certs (Bennett appears at More ville, North Carolina, English house in the spring), have become major, president of the Student annual events. -

Appendix G: School of Graduation

FLORIDA DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION Implementation Date: DOE INFORMATION DATA BASE REQUIREMENTS Fiscal Year 1991-92 VOLUME II: AUTOMATED STAFF INFORMATION SYSTEM July 1, 1991 AUTOMATED STAFF DATA ELEMENTS APPENDIX G SCHOOL OF GRADUATION Revised: 11/89 Volume II Effective: 7/98 Page Number: 161 SCHOOL OF GRADUATION (FICE CODE) STATE: AK FICE INSTITUTION FICE INSTITUTION CODE NAME CODE NAME 11462 ALASKA ANCHORAGE, UNIV OF, 29117 ALASKA BIBLE COLLEGE 11463 ALASKA JUNEAU, UNIV OF, 01061 ALASKA PACIFIC UNIVERSITY 01063 ALASKA-FAIRBANKS,U OF 01064 ANCHORAGE COMM COLLEGE 29016 INUPIAT U OF THE ARTIC 01065 JUNEAU-DOUGLAS COMM COLL 01066 KENAI PENINSULA COMM COL 01067 KETCHIKAN COMM COLLEGE 08315 KODIAK CMTY COLLEGE 11045 KUS KOKWIN CC 00103 AND CLAIMS COLLEGE 01068 MATNUSKA-SUSTINA COLLEGE 29245 NORTHWEST CC 01062 SHELDON JACKSON COLLEGE 01069 SITKA COM COLLEGE 29141 STRATTON JOINT LIBRARY 29093 TANANA VALLEY CC 29095 U ALAS ANCHORAGE ALL CAM 29094 U ALAS FAIRBANKS ALL CAM 29009 U ALASKA ANCHORAGE JT LIB 29096 U ALASKA STHESTN ALL CAM 08698 U ALASKA SYS ALL INSTN 08005 U OF ALAS SYS HI ED SYS Revised 11/91 Volume II Effective 7/98 Page Number 162 SCHOOL OF GRADUATION (FICE CODE) STATE: AL FICE INSTITUTION FICE INSTITUTION CODE NAME CODE NAME 12308 AIR FORCE, CC OF THE 29452 AL CHRISTIAN SCH OF REL 00835 AL CHRISTIAN SCH OF RELGI 05749 ALA AVN AND TECH COLLEGE 01002 ALABAMA A & M UNIVERSITY 01052 ALABAMA AT BIRMINGHAM,U 01055 ALABAMA IN HUNTSVILLE,U 00709 ALABAMA ST. NORMAL SCHOOL 01005 ALABAMA STATE UNIVERSITY 08004 ALABAMA SYSTEM OFF, U OF 05706 -

Methodism's Splendid Mission: the Black Colleges

Methodist History, 22:3 (April /984) METHODISM'S SPLENDID MISSION: THE BLACK COLLEGES JAMES S. THOMAS In the past, many historians of higher education often accepted the twin generalizations that black colleges, (1) "while collegiate in name, did not remotely resemble a college in standards or facilities,"l and (2) that the history of these colleges, while probably important as early hTi'Ssionary ventures, would hardly rate complete chapters in general histories of higher education. This essay begins as a direct challenge to both points of view. Among otheT propositions, it will be argued (1) that, while the contrast between the facilities and standards ofblack and white colleges is dramatically real, it is by no means an unbroken contrast, and (2) admitting the truth of the missionary beginnings of the early black colleges, there is a much greater story of their survival and their production of a group of leaders whose quality stands high on any national standard of leadership. Indeed, the major purpose of this essay is not to argue a particular point, such as any one of the too-easy generalizations of many historians, but to tell the remarkable story of the black colleges of the United Methodist Church. The Earliest of Foundations The history of the black colleges, like that of all institutional history, J predated the founding of any particular institution. Perhaps it is important 1 for United Methodists to remember, in this bicentennial year, that the founder of Methodism, John Wesley, held very strong views about educa,. tion and the worth of every human being. -

CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION in the Period Immediately Following The

CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION In the period immediately following the close of the Civil War, philanthropic endeavors were undertaken to reconstruct secessionist states, establish wide-scale peace among still- hostile factions, and develop efforts to enact social, legal, and educational support. This philanthropic era is characterized by the activities of a number of individual, denominational, organizational, including state and federal supporters that were subsequently responsible for engendering a Negro College Movement, which established institutions for providing freed slaves, and later, Negroes with advanced educational degrees. This dissertation studied: the genesis, unfolding, contributions, and demise issues in conjunction with the social, economic, and political forces that shaped one such institution in Harper’s Ferry (Jefferson County), West Virginia: Storer College, which was founded in 1865 as an outgrowth of several mission schools. By an Act of Congress, in 1868, the founders of Storer College initially were granted temporary use of four government buildings from which to create their campus.1 Over the next 90 years, until its closure in 1955, the college underwent four distinct developmental phases: (a) Mission School [Elementary], (b) Secondary Division, (c) a Secondary Expansion, and (d) Collegiate. Even today—as a result of another Act of Congress—it continues to exist, albeit in altered form: in 1960, the National Park Service branch of the United States Department of the Interior was named the legal curator of the 1 United States. Congress. Legislative, Department of War. An Act Providing for the Sale of Lands, Tenements, and Water Privileges Belonging to the United States at or Near Harpers Ferry, in the County of Jefferson, West Virginia (1868). -

2019 - 2020 Undergraduate Catalog

VIRGINIA UNION UNIVERSITY RRIICCHHMMOONNDD,, VVIIRRGGIINNIIAA 2019 - 2020 UNDERGRADUATE CATALOG i VIRGINIA UNION UNIVERSITY Founded in 1865 Richmond, Virginia 2019 - 2020 CATALOG Rights reserved - - - Virginia Union University (VUU) reserves the right to change the information, regulations, requirements, and procedures announced in this catalog. VUU does not discriminate on the basis of race, sex, color, religion, national origin, age, disability, or veteran status, sexual orientation, gender identity or genetic information. We value a learning community in which all members feel secure physically and intellectually. ii ALMA MATER Union, we’ll e’re revere the cause for which you stand; Union! Majestic light, send rays throughout the land; Thy hallowed grounds and dear old walls, May they forever be, Dear Union, we still love thee; Thy hallowed grounds and dear old walls, May they forever be, Dear Union, we still love thee. O, for the happy hours we spend On that cherished and sacred hill; Our ‘Dream of joy’ to us attends, With truth and virtue to instill; Thoughts of by-gone days at thy shrine Fill my raptured soul with ecstasy, Alma Mater, my praises are Thine! You are God’s gift to humanity. Union, we’ll e’re revere the cause for which you stand; Union! Majestic light, send rays throughout the land; Thy hallowed grounds and dear old walls, May they forever be, Dear Union, we still love thee; Thy hallowed grounds and dear old walls, May they forever be, Dear Union, we still love thee. William H. Yancey Class of 1933 1 A SPECIAL GREETING FROM THE PRESIDENT! Welcome to Virginia Union University! I invite you to explore our broad array of outstanding academic programs, which prepare you for a lifetime of personal discovery and professional achievement. -

The Affirmative Duty to Integrate in Higher Education

Notes The Affirmative Duty to Integrate in Higher Education I. Introduction In the sixteen years since Brown v. Board of Education,' there has been an evolutionary expansion of the duty to desegregate state ele- mentary and secondary school systems once segregated by law. Southern higher education, however, is today marked by racial separation and by a general inferiority of the historically Negro colleges. This Note will consider whether the Supreme Court's holding in Green v. School Board of New Kent County, Virginia2 has any implications for higher educa- tion. The specific questions to be answered are: (1) since there is still a racially identifiable dual system of public higher educational institu- tions in the South, do the states have a duty to take affirmative steps (beyond establishing racially nondiscriminatory admissions policies) to encourage integration; and (2) if such a duty exists, how do the current circumstances of higher education condition the scope of duty and the remedies which courts may enforce? The need for standards8 to measure a state's compliance with Brown in higher education is particularly acute because the Office of Civil Rights for the Department of Health, Education and Welfare has required several states4 to submit plans 1. 347 U.S. 483 (1954) [hereinafter cited as Brown I]. The second Brown decision, on the question of relief, appears at 349 U.S. 294 (1955) [hereinafter cited as Brown 1I]. 2. 391 U.S. 430 (1968) [hereinafter cited as Green]. 3. The desegregation regulations for elementary and secondary education, 45 C.1,.R. §§ 181.1-181.7 (1968), promulgated by HEWt under Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1961, 42 U.S.C. -

Missouri State Association of Negro Teachers OFFICIAL PROGRAM Fifty-Third Annual Convention KANSAS CITY, MO

Missouri State Association of Negro Teachers OFFICIAL PROGRAM Fifty-Third Annual Convention KANSAS CITY, MO. NOV. 16 - 17 - 18 - 19, 1938 LLOYD W. KING Lloyd W. King Democratic Nominee for Re-Election As STATE SUPERINTENDENT OF PUBLIC SCHOOLS For the past four years, Missouri Schools have marched forward under Superintendent Lloyd W. King’s leadership. Through the cooperation of the state administration, the legislature, educators, and lay people interested in education, schools have been adequately financed; standards for teachers have been materially raised; the curricula have been revised; many new services have been extended to schools; vocational education has been broadened; a program of vocational rehabilitation for physically-handicapped persons and a program of distributive education have been inaugurated. THE JOURNAL OF EDUCATION LINCOLN HIGH SCHOOL KANSAS CITY General Officers Burt A. Mayberry President Kansas City Miss Emily Russell Second Vice-President St. Louis C. C. Damel First Vice-President St. Joseph Miss Daisy Mae Trice Assistant Secretary Kansas City U. S. Donaldson Secretary St. Louis Miss Dayse F. Baker Treasurer Farmington Miss Bessie Coleman Assistant Secretary St. Louis L. S. Curtis Statistician St. Louis M. R. Martin Auditor Louisiana A. A. Dyer Editor of the Journal St. Louis W. R. Howell Historian Kansas City Joe E. Herriford, Sr. Parlimentarian Kansas City Dayse F. Baker, BURT A. MAYBERRY, DAISY M. TRICE EXECUTIVE BOARD Burt A. Mayberry, Kansas City Chairman U. S. Donaldson, St. Louis Secretary Miss Dayse F. Baker Farmington Mrs. Lillian Booker Liberty Charles H. Brown St. Louis Miss Bessie Coleman St. Louis H. O. Cook Kansas City H. -

State-Supported Higher Education Among Negroes in the State of Florida

Florida Historical Quarterly Volume 43 Number 2 Florida Historical Quarterly, Vol 43, Article 3 Number 2 1964 State-Supported Higher Education Among Negroes in the State of Florida Leedell W. Neyland [email protected] Part of the American Studies Commons, and the United States History Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/fhq University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Article is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Florida Historical Quarterly by an authorized editor of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Recommended Citation Neyland, Leedell W. (1964) "State-Supported Higher Education Among Negroes in the State of Florida," Florida Historical Quarterly: Vol. 43 : No. 2 , Article 3. Available at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/fhq/vol43/iss2/3 Neyland: State-Supported Higher Education Among Negroes in the State of Fl STATE-SUPPORTED HIGHER EDUCATION AMONG NEGROES IN THE STATE OF FLORIDA by LEEDELL W. NEYLAND TATE-SUPPORTED HIGHER EDUCATION among Negroes in s Florida had its beginning during the decade of the 1880’s. The initial step in this new educational venture was taken by Governor William D. Bloxham who, during his first administra- tion, vigorously set forth a threefold economic and social program. In his inaugural address he declared that in order to promote the interest, welfare, and prosperity of the state, “we must in- vite a healthy immigration; develop our natural resources by se- curing proper transportation; and educate the rising generation.’’ 1 He promulgated this combination as “the three links in a grand chain of progress upon which we can confidently rely for our future growth and prosperity.’’ 2 During his four years in office, 1881-1885, Governor Blox- ham assidiously endeavored to implement his inaugural pledges. -

Educational Directory 1°30

UNITED STATESDEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR RAY LYMAN WILBUR. Secretary s. OFFICE OF EDUCATION WILLIAM JOHN COOPER. Commissioner BULLETIN, 1930, No. 1 EDUCATIONAL DIRECTORY 1°30 1 --"16. ,0 DANIA el 9-111911,- , Al.. s."2:1,_ 111 %. a a. Al. UNITED STATES GOVEANNIENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON:1930 - bes oh by the Swerintendept ofDocuments, Yashington, D. C. e . Price 30 casts o ) ..:41 1\1 456391 g. JUrl-71118 AC4 1,69 \ '30 ,1101141117111.... swim r-" R :7) - - -.40- - t .1.111= CONTENTS I 1 Page I. United StatesOffice ofEducation___ _ _ 1 II. PrincipalState schoolofficers .. ______ .. ... s .;2 III. Countyand other localsuperintendents of schools'_ _...... _ .............. 16 Iv. Superintendentsof public schoolsin cities andtowns 40 I V. Public-schoolbusiness managers_______- ____---.--..... --- 57, VI. Presidentsof tiniversitiesand colleges 58 VII. Presidents of juniorcolleges _ , 65 VIII. Headsof departmentsof education_ 68 "P r Ix. Presidentsor WM OW .N. deans of sehoolsof theology__ m =0 MMM .. ../ Mt o. w l0 X. Presidentsordeans of schools oflaw _ 78 XI. Presidentsor deans of schools of medicinP M Mo". wt. MP OM mm .. 80 XII. Presidentsordeans of schoolsof dentistry__.---- ___--- - 82 XIII. Prusidentsordeans of dchoolsof pharmacy_____ .. 82 XIV. PNsidentsofrschools ofosteopathy : 84 XV. Deansof schools ofveterinary medicine . 84 XVI. Deansof collegiateschools ofcommerce 84 XVII. Schools, colleges,ordepartments ofengineering _ 86 XVIII. Presidents,etc., of institutions forthetraini;igof teachers: , (1) Presidents ofteachers colleges__:__aft do am IND . _ . _ 89 (2) Principals of Statenormal schools_______ _ N.M4, 91 (3) Principals ofcity public normalschools___ __ _ 92 (4) Principals ofprivate physicaltraining schoolss.,__ _ 92 (5) Prinoipals ofprivatenursery,kindergarten, andprimary training schools 93 (6) Principals of privategeneral training schools 93 XIX. -

2013-2015 Catalog

2013-2015 2011-2013 CATALOG N COMMUNITY CO COMMUNITY N L O C COPIAH-LIN EGE LL 2013 - 2015 COPIAH-LINCOLN COMMUNITY COLLEGE CATALOG 39191 PAID US Postage Wesson, MS Wesson, Permit No. 20 Non-Profit Org. Address Service Requested P.O. Box 649 • Wesson, MS 39191 MS Wesson, • 649 Box P.O. 1 COPIAH-LINCOLN COMMUNITY COLLEGE 99th - 100th ANNUAL SESSIONS Announcements for 2013-2015 Wesson Campus Natchez Campus Simpson County Center . THE PLACE TO BE 2 DIRECTORY OF INFORMATION Copiah-Lincoln Community College Wesson Campus P.O. Box 649 (Mailing Address) 1001 Copiah Lincoln Lane (Physical Address) Wesson, MS 39191 Telephone: (601) 643-5101 Copiah-Lincoln Community College Copiah-Lincoln Community College Natchez Campus Simpson County Center 11 Co-Lin Circle 151 Co-Lin Drive Natchez, MS 39120 Mendenhall, MS 39114 Telephone: (601) 442-9111 Telephone: (601) 849-5149 E-mail addresses can be found at our website: www.colin.edu AFFILIATIONS Copiah-Lincoln Community College is accredited by the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools Commission on Colleges to award Associate in Arts and Associate in Applied Science degrees. Contact the Commission on Colleges at 1866 Southern Lane, Decatur, Georgia 30033-4097 or call 404-679-4500 for questions about the accreditation of Copiah-Lincoln Community College. The commission is only to be contacted if there is evidence that appears to support an institution’s significant non-compliance with a requirement or standard. All normal inquiries about the institution, such as admission requirements, financial aid, educational programs, and other college-related information should be addressed directly to the College and not to the office of the Commission on Colleges.