'A Path for Understanding': Journey Metaphors in (Three) Early Greek Philosophers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jebb's Antigone

Jebb’s Antigone By Janet C. Collins A Thesis submitted to the Graduate Program in Classics in conformity with the requirements for the Master of Arts Queen’s University Kingston, Ontario, Canada August 2015 Copyright Janet Christine Collins, 2015 I dedicate this thesis to Ross S. Kilpatrick Former Head of Department, Classics, Queen’s University, Kingston, Ontario. Who of us will forget his six-hour Latin exams? He was a very open-minded prof who encouraged us to think differently, he never criticized, punned us to death and was a thoroughly good chap. And to R. Drew Griffith My supervisor, not a punster, but also very open-minded, encouraged my wayward thinking, has read everything and is also a thoroughly good chap. And to J. Douglas Stewart, Queen’s Art Historian, sadly now passed away, who was more than happy to have long conversations with me about any period of history, but especially about the Greeks and Romans. He taught me so much. And to Mrs. Norgrove and Albert Lee Abstract In the introduction, chapter one, I seek to give a brief oversight of the thesis chapter by chapter. Chapter two is a brief biography of Sir Richard Claverhouse Jebb, the still internationally recognized Sophoclean authority, and his much less well-known life as a humanitarian and a compassionate, human rights–committed person. In chapter three I look at δεινός, one of the most ambiguous words in the ancient Greek language, and especially at its presence and interpretation in the first line of the “Ode to Man”: 332–375 in Sophocles’ Antigone, and how it is used elsewhere in Sophocles and in a few other fifth-century writers. -

Being Suneches, Being Continuous, Is a Central Notion in Aristotle

1 The notion of continuity in Parmenides1 1. Introduction: Being suneches, being continuous, is a central notion in Aristotle’s Physics, and of crucial importance for understanding time, space, and motion within Aristotle’s framework. In this paper I want to show that continuity is, however, already of crucial philosophical significance in Parmenides, who seems to be the first thinker in the West to use the notion of continuity in a philosophically interesting and systematic way. But Parmenides uses it in a way that is importantly different from Aristotle with opposing implications. The notion of suneches itself has not attracted much attention from Parmenides scholars (even though the passages in which Parmenides talks about suneches have, and their understanding is highly disputed).2 What I will do in this paper is to look first in some detail at the three passages in fragment 8 of Parmenides’ poem that are of crucial importance for Parmenides’ notion of being suneches before comparing it briefly to Aristotle’s notion. An analysis of these three passages in Parmenides will show that suneches for Parmenides implies complete homogeneity and indivisibility. The three passages I look at are (1) fragment 8, lines 5-6a, where Parmenides calls what is (eon) “suneches” for the first time and links being suneches and being homou (‘being together’). (2) Lines 22-25 show being suneches to exclude differences in kind as well as any more or less. (3) Lines 42-49, finally, even though not using the word “suneches”, can be understood as taking up the discussion of conditions that would prevent eon from being suneches and as systematizing these conditions. -

CAMBRIDGE GREEK and LATIN CLASSICS General Editors P. E

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-88332-0 - Iliad: Book XXII Homer Frontmatter More information CAMBRIDGE GREEK AND LATIN CLASSICS G eneral E ditors P. E . E asterling Regius Professor Emeritus of Greek, University of Cambridge P hilip H ardie Senior Research Fellow, Trinity College, and Honorary Professor of Latin, University of Cambridge R ichard H unter Regius Professor of Greek, University of Cambridge E. J. Kenney Kennedy Professor Emeritus of Latin, University of Cambridge S. P. Oakley Kennedy Professor of Latin, University of Cambridge © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-88332-0 - Iliad: Book XXII Homer Frontmatter More information © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-88332-0 - Iliad: Book XXII Homer Frontmatter More information HOMER ILIAD BOOK XXII edited by IRENE J. F. DE JONG Professor of Ancient Greek University of Amsterdam © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-88332-0 - Iliad: Book XXII Homer Frontmatter More information University Printing House, Cambridge cb2 8 bs, United Kingdom Cambridge University Press is part of the University of Cambridge. It furthers the University’s mission by disseminating knowledge in the pursuit of education, learning and research at the highest international levels of excellence. www.cambridge.org Information on this title: www.cambridge.org/9780521709774 c IreneJ.F.deJong2012 This publication is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. -

The Definition of Myth. Symbolical Phenomena in Ancient Culture

The definition of myth. Symbolical phenomena in ancient culture Synm'JVe des Bouvrie Introduction THE PRESENT article aims at making a contribution to the definition of myth as well as to the discussion about the substance of what is commonly referred to as 'myth.' It does not pretend to give the final answer to all questions related to this intricate problem, but to offer some clarification at the present moment, when the term 'myth' is freely in use among classical scholars without always being suffi ciently defined. In fact the question of definition seems indeed to be avoided. In addressing this question I will proceed along two lines and study the nature and 'existence' of myth from a social as well as from a biological point of view. We have to ask how 'myth' operates in the particular culture we are studying, and to con sider how the human mind does in fact function in a special 'mythical' way, stud ying its relationship to conscious reasoning. By adducing insights from anthropological theory I hope to contribute to the definition of the term and by presenting some results from psychology I wish to substantiate the claim that 'mythical phenomena' can be said to be generated by some 'mythical mind.' Both answers amount to the conclusion that 'myth' does in fact exist, if we study what I provisionally call 'myth' as a subspecies of what commonly is labelled 'symbolic phenomena.' This term refers to processes and entities which constitute a complex force in the creation and maintenance of culture. My justification for these choices is the situation that within our field of classi cal studies we are deprived of studying phenomena like 'myth' within their living context. -

A BIBLIOGRAPHICAL and PHILOSOPHICAL STUDY Infinity in the Presocratics: a Bmliographical and PHILOSOPHICAL STUDY

INFINITY IN THE PRESOCRA TICS: A BIBLIOGRAPHICAL AND PHILOSOPHICAL STUDY Infinity in the Presocratics: A BmLIOGRAPHICAL AND PHILOSOPHICAL STUDY by LEO SWEENEY, S. J. The Catholic University of America Foreword by JOSEPH OWENS, C. S8. R. Pontifical Institute of Mediaeval Studies II MARTINUS NIJHOFF / THE HAGUE /1972 @ 1972 by Martinus Nijhoff, The Hague, Netherlands All rights reserved, including the right to translate or to reproduce this book or parts thereof in any form ISBN-13:978-90-247-1170-3 e-1SBN-13:978-94-010-2729-8 DOl: 10.1007/978-94-010-2729-8 To Lee and Adrian Powell, James, John, Jeffrey, Jean, Jay, Jane, Jerry and Mary Ann TABLE OF CONTENTS Abbreviations IX Permissions XIV Foreword by Joseph Owens xvn Introduction xx Mondolfo XXIII Sinnige xxvn Methodology and acknowledgements XXXI CHAPTER ONE: SECONDARY LITERATURE ON ANAXIMANDER 1 Ancient Sources 2 Recent Studies on Anaximander 5 Vlastos, Jaeger, Burch, Kraus 5 Cherniss, Cornford, Matson, McDiarmid 8 HOlscher, Kirk 14 Wisniewski, Kahn 20 Guazzoni Foa, Solmsen, Classen 26 Paul Seligman 29 Guthrie, Gottschalk 33 F. M. Cleve 39 Stokes, Bicknell 41 Other Studies? 49 CHAPTER Two: ANAXIMANDER AND OTHER IONIANS 55 Anaximander 55 Anaximenes, Xenophanes, Heraclitus 65 Conclusion 73 CHAPTER THREE: PYTHAGORAS 74 J. E. Raven 75 vm TABLE OF CONTENTS J. A. Philip 84 Conclusions 91 CHAPTER FOUR: THE ELEATICS 93 Parmenides 93 Burnet, Raven and Guthrie 94 Joseph Owens 97 Loenen 99 Taran 102 Conclusions 105 Zeno 110 Jesse De Boer 112 H. N. Lee 117 Conclusions 119 Melissus 124 Fragment 9 -

Politics, Philosophy, Writing : Plato's Art of Caring for Souls

Politics, Philosophy, Writing: Plato's Art of Caring for Souls Zdravko Planinc, Editor University of Missouri Press Politics, Philosophy, Writing This page intentionally left blank Politics, Philosophy, Writing i PLATO’S ART OF CARING FOR SOULS Edited with an Introduction by Zdravko Planinc University of Missouri Press Columbia and London Copyright © 2001 by The Curators of the University of Missouri University of Missouri Press, Columbia, Missouri 65201 Printed and bound in the United States of America All rights reserved 54321 0504030201 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Politics, philosophy, writing : Plato’s art of caring for souls / edited by Zdravko Planinc. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-8262-1343-X (alk. paper) 1. Plato. I. Planinc, Zdravko, 1953– B395 .P63 2001 184—dc21 00-066603 V∞™ This paper meets the requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, Z39.48, 1984. Designer: Kristie Lee Typesetter: The Composing Room of Michigan, Inc. Printer and Binder: The Maple-Vail Book Manufacturing Group Typeface: Minion For Alexander Tessier This page intentionally left blank Contents Introduction 1 Zdravko Planinc Soulcare and Soulcraft in the Charmides Toward a Platonic Perspective 11 Horst Hutter Shame in the Apology 42 Oona Eisenstadt The Strange Misperception of Plato’s Meno 60 Leon Craig “A Lump Bred Up in Darknesse” Two Tellurian Themes of the Republic 80 Barry Cooper Homeric Imagery in Plato’s Phaedrus 122 Zdravko Planinc “One, Two, Three, but Where Is the Fourth?” Incomplete Mediation in the Timaeus 160 Kenneth Dorter Mystic Philosophy in Plato’s Seventh Letter 179 James M. -

King's College Cambridge

KING’S Summer 2013 Magazine for Members and Friends of King’s College, Cambridge PARADE celebrating 500 years of the chapel: the countdown begins a new approach to teaching the social sciences Professor Sir Geoffrey Lloyd on spending his $1 million prize KING’SWELCOME WELCOME TO THE Provosts past (and future) SUMMER EDITION As King’s prepares to welcome new Provost Michael Proctor this autumn, Librarian Peter Jones reflects on the heretics, alchemists or this issue, I spent an hour with Professor Sir Geoffrey Lloyd, who and necromancers who have held the post in times past. was recently awarded the $1m Dan David Prize for his contribution to The first two Provosts at King’s (William King William nominated Sir Isaac Newton F Millington and John Chedworth, since you as Provost in 1689. If we never had the our understanding of the modern legacy of the ancient world (see interview, pages ask) are best described as inquisitors. benefit of Newton as Provost, we ended up 4 and 5). Geoffrey’s work has always Apart from heading the College, their main as custodians of his alchemical papers, spanned a wide range of subjects, and his claim to fame is that they both tried, in thanks to Keynes’s bequest in 1946. interdisciplinary approach is increasingly the end successfully, to convict Bishop One Provost was reputed to be a being recognised as the most fruitful way Reginald Pecock of heresy. He lost his necromancer – Roger Goad. He survived to conduct research. bishopric for the crime of writing in English. forty years in office from his election in 1570 The trend can be seen, for example, In the 16th century, several Provosts despite the plots of junior Fellows to remove in the revolution in the way the social themselves were condemned as heretics. -

The Iliad of Homer, Books I-XII (Volume 1)

The Iliad of Homer, Books I-XII (Volume 1) The Iliad of Homer, Books I-XII (Volume 1) Translated by Barry Nurcombe The Iliad of Homer, Books I-XII (Volume 1) Translated by Barry Nurcombe This book first published 2020 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2020 by Barry Nurcombe All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-5275-5439-2 ISBN (13): 978-1-5275-5439-9 TABLE OF CONTENTS: VOLUME 1 Acknowledgements .................................................................................. vii Introduction ............................................................................................... ix Pronunciation .......................................................................................... xlvi Maps ..................................................................................................... xlviii Book I: Pestilence and Wrath ..................................................................... 1 Book II: The Dream, Boiōtía and The Catalogue of Ships ....................... 43 Book III: The Truce. The View from the Ramparts. The Duel of Páris and Menélaos ......................................................................................... -

Epicurean Justice and Law

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2016 Epicurean Justice and Law Jan Maximilian Robitzsch University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Classics Commons, Philosophy Commons, and the Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Robitzsch, Jan Maximilian, "Epicurean Justice and Law" (2016). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 1976. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/1976 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/1976 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Epicurean Justice and Law Abstract This dissertation concerns a cluster of related issues surrounding the Epicurean conception of justice. First, I show that the Epicureans defend a sophisticated kind of social contract theory and maintain a kind of legal positivism, views that are widely held today and so are of continuing interest for contemporary readers. In doing so, I argue that thinking about justice and law forms an integral part of Epicurean philosophy (pace the standard view). Second, I take up some neglected issues regarding justice and so provide detailed accounts of the metaphysics of moral properties in Epicureanism as well as of Epicurean moral epistemology. After the introduction in chapter 1, I set out the main features of the Epicurean view of justice and law in chapters 2-4. In chapter 2, I explain the basics of the Epicurean conception of justice as an agreement and relate it to Epicurean ethics as whole. In chapter 3, I examine Epicurean culture stories and I point out in what way the Epicurean view is a kind of social contract theory. -

The Nature of Greek Myths, 1974, 332 Pages, Geoffrey Stephen Kirk, Penguin Books, 1974

The nature of Greek myths, 1974, 332 pages, Geoffrey Stephen Kirk, Penguin Books, 1974 DOWNLOAD http://bit.ly/1TMrJjW http://www.barnesandnoble.com/s/?store=book&keyword=The+nature+of+Greek+myths Puts forth original theories concerning the origins and cultural significance of the Greek myths DOWNLOAD http://t.co/kKkqbOngjB http://bit.ly/1o52BSM Greek Mythology , John Pinsent, Sep 1, 1990, Mythen., 144 pages. Analyzes the development and social significance of the myth in Grecian society in addition to describing the exploits and physical attributes of individual gods and heroes. University of Kansas Publications: Humanistic studies, Issue 32 Humanistic studies, University of Kansas, 1955, Humanities, . The Songs of Homer , G. S. Kirk, Feb 17, 2005, History, 456 pages. A vivid and comprehensive account of the Homeric poems and their quality as literature.. Gods, Goddesses, and Mythology, Volume 5 , , 2005, Mythology, 1584 pages. More than three hundred alphabetically arranged entries cover mythological beings, themes, and deities from around the world.. The Iliad A Commentary. Books 21-24. Volume VI, Nicholas James Richardson, Geoffrey Stephen Kirk, 1993, Achilles (Greek mythology) in literature, 387 pages. This is the sixth and final volume of the major Commentary on Homer's Iliad issued under the General Editorship of Professor G. S. Kirk.. Favorite Greek Myths , Bob Blaisdell, Robert Blaisdell, 1995, Juvenile Fiction, 96 pages. Retells the stories of the Golden Fleece, the Trojan War, Hercules, and other Greek myths.. Ancient Myth in Art and Literature , Phillip Stanley, Patricia Johnston, Jan 8, 2004, Social Science, 320 pages. Myth. Its Meaning and Functions in Ancient and Other Cultures , Geoffrey Stephen Kirk, 1970, Mythology, 299 pages. -

Jean Bollack in English, a Preview of a Foreword to the Art of Reading, Part I

Jean Bollack in English, a preview of a foreword to The Art of Reading, Part I The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Nagy, Gregory. 2016.03.10. "Jean Bollack in English, a preview of a foreword to The Art of Reading, Part I". Classical Inquiries. http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:hul.eresource:Classical_Inquiries. Published Version https://classical-inquiries.chs.harvard.edu/jean-bollack-in-english- a-preview-of-a-foreword-to-the-art-of-reading-part-vi/ Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:39666453 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Classical Inquiries Editors: Angelia Hanhardt and Keith Stone Consultant for Images: Jill Curry Robbins Online Consultant: Noel Spencer About Classical Inquiries (CI ) is an online, rapid-publication project of Harvard’s Center for Hellenic Studies, devoted to sharing some of the latest thinking on the ancient world with researchers and the general public. While articles archived in DASH represent the original Classical Inquiries posts, CI is intended to be an evolving project, providing a platform for public dialogue between authors and readers. Please visit http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:hul.eresource:Classical_Inquiries for the latest version of this article, which may include corrections, updates, or comments and author responses. Additionally, many of the studies published in CI will be incorporated into future CHS pub- lications. -

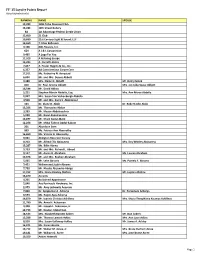

FY '15 Loyalty Points Report (Listed Alphabetically)

FY '15 Loyalty Points Report (listed alphabetically) RANKING NAME SPOUSE 13,283 1995 Tribe Diamond Club 13,284 19th Street Gallery 82 1st Advantage Federal Credit Union 12,600 21 Club 10,660 21st Century Sight & Sound, LLC 14,669 7 Cities Ballroom 4,108 800-Flowers, Inc. 654 A J & L Corporation 9,495 A Logo For You 11,923 A Relaxing Escape 13,285 A. Carroll's Bistro 7,427 A. Foster Higgins & Co., Inc. 6,337 AA Conscientious Carpet Care 17,911 Ms. Katherine N. Aanestad 6,604 Mr. and Mrs. Dennis Abbott 9,988 Mrs. Elaine H. Abbott Mr. Henry Mook 818 Dr. Paul Jerome Abbott Mrs. Jan Laberteaux Abbott 18,544 Mr. David Abbou 5,231 Stephen Martin Abdella, Esq. Mrs. Ann Morse Abdella 2,947 Mrs. Susan Van Volkenburgh Abdella 4,506 Mr. and Mrs. Samir J. Abdennour 463 Dr. Diane D. Abdo Dr. Robert John Abdo 13,286 Ms. Thomasina Abdoe 3,383 Mr. Maziar Abdolrasulnia 5,990 Mr. Rasul Abdolrasulnia 14,877 Mr. Khalil Abdul-Malik 12,256 Mr. Mikal Tahron Abdul-Saboor 201 Aberdeen Barn 899 Ms. Patricia Ann Abernathy 16,469 Ms. Valerie G. Abernathy 9,991 Abington Recorder Society 9,213 Mr. Alfred Ellis Abiouness Mrs. Kay Whitley Abiouness 13,287 Ms. Billie Abney 9,753 Mr. and Mrs. Richard L. Abood 9,127 Mr. Aaron B. Abraham Ms. Lauren Abraham 14,878 Mr. and Mrs. Reuben Abraham 5,065 Mr. Lehn Abrams Ms. Pamela F. Abrams 7,421 William and Judith Abrams 7,792 Mr. Nicolas Alejandro Abrigo 17,912 Mrs.