Being Suneches, Being Continuous, Is a Central Notion in Aristotle

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Curriculum Vitae

1 Geoffrey Lloyd PUBLICATIONS I BOOKS 1966 Polarity and Analogy: two types of argumentation in early Greek thought, pp. v + 503, Cambridge University Press reprinted 1987 Bristol University Press; translations: Spanish 1987, Italian 1992: Korean forthcoming 1968 Aristotle: The Growth and Structure of his Thought, pp. xiii + 324, Cambridge University Press; translations: Japanese 1973, Italian 1985, Chinese 1985, Spanish 2008 1970 Early Greek Science: Thales to Aristotle, pp. xvi + 156, Chatto and Windus; translations: Spanish 1973, French 1974, Italian 1978, Japanese 1995, French 2nd ed. 1990, Korean 1996, Chinese 2005, Greek 2005, Polish forthcoming. 1973 Greek Science after Aristotle, pp. xiii + 189, Chatto and Windus; translations: Italian 1978, French 1990, Japanese 2000, Greek 2007 Slovene 2009, Polish forthcoming.. 1979 Magic, Reason and Experience, pp. xii + 335, Cambridge University Press; reprinted 1999 Bristol Classical Press; translations: Italian 1982, French 1990, Greek forthcoming, French 2nd ed 1996 1983 Science, Folklore and Ideology, pp. xi + 260, Cambridge University Press; reprinted 1999 Bristol Classical Press; translations: Italian 1987. 1985 Science and Morality in Greco-Roman antiquity, (Inaugural Lecture) pp. 29, Cambridge University Press. 1987 The Revolutions of Wisdom, pp. xii + 468, University of California Press, Berkeley; translations: Italian forthcoming. 1990 Demystifying Mentalities, pp. viii + 174, Cambridge University Press; translations: Italian 1991, French 1994, Spanish 1996. 1991 Methods and Problems in Greek Science, pp. xiv + 457, Cambridge University Press; translations: Italian 1993, Rumanian 1995, Greek 1996. 2 1996 Adversaries and authorities, pp. xvii + 250, Cambridge University Press 1996 Aristotelian explorations pp. ix + 242, Cambridge University Press 2002 The Ambitions of Curiosity pp. xxi + 175, Cambridge University Press translations Italian 2003, Spanish 2008 2002 The Way and the Word (with Nathan Sivin) pp. -

Jebb's Antigone

Jebb’s Antigone By Janet C. Collins A Thesis submitted to the Graduate Program in Classics in conformity with the requirements for the Master of Arts Queen’s University Kingston, Ontario, Canada August 2015 Copyright Janet Christine Collins, 2015 I dedicate this thesis to Ross S. Kilpatrick Former Head of Department, Classics, Queen’s University, Kingston, Ontario. Who of us will forget his six-hour Latin exams? He was a very open-minded prof who encouraged us to think differently, he never criticized, punned us to death and was a thoroughly good chap. And to R. Drew Griffith My supervisor, not a punster, but also very open-minded, encouraged my wayward thinking, has read everything and is also a thoroughly good chap. And to J. Douglas Stewart, Queen’s Art Historian, sadly now passed away, who was more than happy to have long conversations with me about any period of history, but especially about the Greeks and Romans. He taught me so much. And to Mrs. Norgrove and Albert Lee Abstract In the introduction, chapter one, I seek to give a brief oversight of the thesis chapter by chapter. Chapter two is a brief biography of Sir Richard Claverhouse Jebb, the still internationally recognized Sophoclean authority, and his much less well-known life as a humanitarian and a compassionate, human rights–committed person. In chapter three I look at δεινός, one of the most ambiguous words in the ancient Greek language, and especially at its presence and interpretation in the first line of the “Ode to Man”: 332–375 in Sophocles’ Antigone, and how it is used elsewhere in Sophocles and in a few other fifth-century writers. -

Illinois Classical Studies

UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS LIBRARY AT URBANA-CHAMPAIGN CLASSICS The Minimum Fee for NOTICE: Return or renew all Library Materialsl each Lost Book is $50.00. for The person charging this material is responsible it was withdrawn its return to the Ubrary from which below. on or before the Latest Date stamped are reasons for discipli- TheM, mutilation, and underlining of books from the University. nary action and may result in dismissal 333-8400 To renew call Telephone Center, URBANA-CHAMPAIGN UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS LIBRARY AT L161—O-1096 <2.<-K S^f-T? ILLINOIS CLASSICAL STUDIES VOLUME XI. 1 &2 SPRING/FALL 1986 J. K. Newman, Editor ISSN 0363-1 923 ILLINOIS CLASSICAL STUDIES VOLUME XI 1986 J. K. Newman, Editor Patet omnibus Veritas; nondum est occupata; multum ex ilia etiam futuris relictum est. Sen. Epp. 33. 11 SCHOLARS PRESS ISSN 0363-1923 ILLINOIS CLASSICAL STUDIES VOLUME XI Problems of Greek Philosophy ©1986 The Board of Trustees University of Illinois Copies of the journal may be ordered from: Scholars Press Customer Services P.O. Box 6525 Ithaca, New York 14851 Printed in the U.S.A. ADVISORY EDITORIAL COMMITTEE John J. Bateman David F. Bright Howard Jacobson Miroslav Marcovich Responsible Editor: J. K. Newman The Editor welcomes contributions, which should not normally exceed twenty double-spaced typed pages, on any topic relevant to the elucidation of classical antiquity, its transmission or influence. Con- sistent with the maintenance of scholarly rigor, contributions are especially appropriate which deal with major questions of interpre- tation, or which are likely to interest a wider academic audience. -

CAMBRIDGE GREEK and LATIN CLASSICS General Editors P. E

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-88332-0 - Iliad: Book XXII Homer Frontmatter More information CAMBRIDGE GREEK AND LATIN CLASSICS G eneral E ditors P. E . E asterling Regius Professor Emeritus of Greek, University of Cambridge P hilip H ardie Senior Research Fellow, Trinity College, and Honorary Professor of Latin, University of Cambridge R ichard H unter Regius Professor of Greek, University of Cambridge E. J. Kenney Kennedy Professor Emeritus of Latin, University of Cambridge S. P. Oakley Kennedy Professor of Latin, University of Cambridge © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-88332-0 - Iliad: Book XXII Homer Frontmatter More information © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-88332-0 - Iliad: Book XXII Homer Frontmatter More information HOMER ILIAD BOOK XXII edited by IRENE J. F. DE JONG Professor of Ancient Greek University of Amsterdam © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-88332-0 - Iliad: Book XXII Homer Frontmatter More information University Printing House, Cambridge cb2 8 bs, United Kingdom Cambridge University Press is part of the University of Cambridge. It furthers the University’s mission by disseminating knowledge in the pursuit of education, learning and research at the highest international levels of excellence. www.cambridge.org Information on this title: www.cambridge.org/9780521709774 c IreneJ.F.deJong2012 This publication is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. -

The Definition of Myth. Symbolical Phenomena in Ancient Culture

The definition of myth. Symbolical phenomena in ancient culture Synm'JVe des Bouvrie Introduction THE PRESENT article aims at making a contribution to the definition of myth as well as to the discussion about the substance of what is commonly referred to as 'myth.' It does not pretend to give the final answer to all questions related to this intricate problem, but to offer some clarification at the present moment, when the term 'myth' is freely in use among classical scholars without always being suffi ciently defined. In fact the question of definition seems indeed to be avoided. In addressing this question I will proceed along two lines and study the nature and 'existence' of myth from a social as well as from a biological point of view. We have to ask how 'myth' operates in the particular culture we are studying, and to con sider how the human mind does in fact function in a special 'mythical' way, stud ying its relationship to conscious reasoning. By adducing insights from anthropological theory I hope to contribute to the definition of the term and by presenting some results from psychology I wish to substantiate the claim that 'mythical phenomena' can be said to be generated by some 'mythical mind.' Both answers amount to the conclusion that 'myth' does in fact exist, if we study what I provisionally call 'myth' as a subspecies of what commonly is labelled 'symbolic phenomena.' This term refers to processes and entities which constitute a complex force in the creation and maintenance of culture. My justification for these choices is the situation that within our field of classi cal studies we are deprived of studying phenomena like 'myth' within their living context. -

Annual Report 2009 Annual Report 2009

King’s College, Cambridge Annual Report 2009 Annual Report 2009 Contents The Provost 2 The Fellowship 7 Undergraduates at King’s 18 Graduates at King’s 24 Tutorial 26 Research 32 Library 35 Chapel 38 Choir 41 Staff 43 Development 46 Members’ Information Form 51 Obituaries 55 Information for Members 259 The first and most obvious to the blinking, exploring, eye is buildings. If The Provost you go to the far side of the Market Place and look back, you now see three tall buildings: Great St Mary’s, King’s Chapel, and a taller Market Hostel. First spiky scaffolding reached above the original roof. Now it has all been shrouded in polythene, like a mystery shop window offering. It’ll stay 2 Things could only get better. You wrapped for a year until the major refit is completed next summer. 3 may remember that when I wrote THE PROVOST these notes last year, I had just Moving back into the main college in my exploratory perambulation, I find discovered that the College had more scaffolding. It’s on the Wilkins Screen. It’s on the Chapel, where through written to the local authorities THE PROVOST the summer we’ve moved down the entire South side, cleaning and treating saying that they were unaware of the glazing bars so that they no longer rust, expand, and prise off bits of the my place of residence. The College stone. Face lifts for the fountain and founder’s statue. So I see much activity, did not know where I was and I expensive activity. -

Politics, Philosophy, Writing : Plato's Art of Caring for Souls

Politics, Philosophy, Writing: Plato's Art of Caring for Souls Zdravko Planinc, Editor University of Missouri Press Politics, Philosophy, Writing This page intentionally left blank Politics, Philosophy, Writing i PLATO’S ART OF CARING FOR SOULS Edited with an Introduction by Zdravko Planinc University of Missouri Press Columbia and London Copyright © 2001 by The Curators of the University of Missouri University of Missouri Press, Columbia, Missouri 65201 Printed and bound in the United States of America All rights reserved 54321 0504030201 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Politics, philosophy, writing : Plato’s art of caring for souls / edited by Zdravko Planinc. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-8262-1343-X (alk. paper) 1. Plato. I. Planinc, Zdravko, 1953– B395 .P63 2001 184—dc21 00-066603 V∞™ This paper meets the requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, Z39.48, 1984. Designer: Kristie Lee Typesetter: The Composing Room of Michigan, Inc. Printer and Binder: The Maple-Vail Book Manufacturing Group Typeface: Minion For Alexander Tessier This page intentionally left blank Contents Introduction 1 Zdravko Planinc Soulcare and Soulcraft in the Charmides Toward a Platonic Perspective 11 Horst Hutter Shame in the Apology 42 Oona Eisenstadt The Strange Misperception of Plato’s Meno 60 Leon Craig “A Lump Bred Up in Darknesse” Two Tellurian Themes of the Republic 80 Barry Cooper Homeric Imagery in Plato’s Phaedrus 122 Zdravko Planinc “One, Two, Three, but Where Is the Fourth?” Incomplete Mediation in the Timaeus 160 Kenneth Dorter Mystic Philosophy in Plato’s Seventh Letter 179 James M. -

King's College Cambridge

KING’S Summer 2013 Magazine for Members and Friends of King’s College, Cambridge PARADE celebrating 500 years of the chapel: the countdown begins a new approach to teaching the social sciences Professor Sir Geoffrey Lloyd on spending his $1 million prize KING’SWELCOME WELCOME TO THE Provosts past (and future) SUMMER EDITION As King’s prepares to welcome new Provost Michael Proctor this autumn, Librarian Peter Jones reflects on the heretics, alchemists or this issue, I spent an hour with Professor Sir Geoffrey Lloyd, who and necromancers who have held the post in times past. was recently awarded the $1m Dan David Prize for his contribution to The first two Provosts at King’s (William King William nominated Sir Isaac Newton F Millington and John Chedworth, since you as Provost in 1689. If we never had the our understanding of the modern legacy of the ancient world (see interview, pages ask) are best described as inquisitors. benefit of Newton as Provost, we ended up 4 and 5). Geoffrey’s work has always Apart from heading the College, their main as custodians of his alchemical papers, spanned a wide range of subjects, and his claim to fame is that they both tried, in thanks to Keynes’s bequest in 1946. interdisciplinary approach is increasingly the end successfully, to convict Bishop One Provost was reputed to be a being recognised as the most fruitful way Reginald Pecock of heresy. He lost his necromancer – Roger Goad. He survived to conduct research. bishopric for the crime of writing in English. forty years in office from his election in 1570 The trend can be seen, for example, In the 16th century, several Provosts despite the plots of junior Fellows to remove in the revolution in the way the social themselves were condemned as heretics. -

The Iliad of Homer, Books I-XII (Volume 1)

The Iliad of Homer, Books I-XII (Volume 1) The Iliad of Homer, Books I-XII (Volume 1) Translated by Barry Nurcombe The Iliad of Homer, Books I-XII (Volume 1) Translated by Barry Nurcombe This book first published 2020 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2020 by Barry Nurcombe All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-5275-5439-2 ISBN (13): 978-1-5275-5439-9 TABLE OF CONTENTS: VOLUME 1 Acknowledgements .................................................................................. vii Introduction ............................................................................................... ix Pronunciation .......................................................................................... xlvi Maps ..................................................................................................... xlviii Book I: Pestilence and Wrath ..................................................................... 1 Book II: The Dream, Boiōtía and The Catalogue of Ships ....................... 43 Book III: The Truce. The View from the Ramparts. The Duel of Páris and Menélaos ......................................................................................... -

The Nature of Greek Myths, 1974, 332 Pages, Geoffrey Stephen Kirk, Penguin Books, 1974

The nature of Greek myths, 1974, 332 pages, Geoffrey Stephen Kirk, Penguin Books, 1974 DOWNLOAD http://bit.ly/1TMrJjW http://www.barnesandnoble.com/s/?store=book&keyword=The+nature+of+Greek+myths Puts forth original theories concerning the origins and cultural significance of the Greek myths DOWNLOAD http://t.co/kKkqbOngjB http://bit.ly/1o52BSM Greek Mythology , John Pinsent, Sep 1, 1990, Mythen., 144 pages. Analyzes the development and social significance of the myth in Grecian society in addition to describing the exploits and physical attributes of individual gods and heroes. University of Kansas Publications: Humanistic studies, Issue 32 Humanistic studies, University of Kansas, 1955, Humanities, . The Songs of Homer , G. S. Kirk, Feb 17, 2005, History, 456 pages. A vivid and comprehensive account of the Homeric poems and their quality as literature.. Gods, Goddesses, and Mythology, Volume 5 , , 2005, Mythology, 1584 pages. More than three hundred alphabetically arranged entries cover mythological beings, themes, and deities from around the world.. The Iliad A Commentary. Books 21-24. Volume VI, Nicholas James Richardson, Geoffrey Stephen Kirk, 1993, Achilles (Greek mythology) in literature, 387 pages. This is the sixth and final volume of the major Commentary on Homer's Iliad issued under the General Editorship of Professor G. S. Kirk.. Favorite Greek Myths , Bob Blaisdell, Robert Blaisdell, 1995, Juvenile Fiction, 96 pages. Retells the stories of the Golden Fleece, the Trojan War, Hercules, and other Greek myths.. Ancient Myth in Art and Literature , Phillip Stanley, Patricia Johnston, Jan 8, 2004, Social Science, 320 pages. Myth. Its Meaning and Functions in Ancient and Other Cultures , Geoffrey Stephen Kirk, 1970, Mythology, 299 pages. -

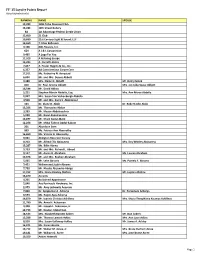

FY '15 Loyalty Points Report (Listed Alphabetically)

FY '15 Loyalty Points Report (listed alphabetically) RANKING NAME SPOUSE 13,283 1995 Tribe Diamond Club 13,284 19th Street Gallery 82 1st Advantage Federal Credit Union 12,600 21 Club 10,660 21st Century Sight & Sound, LLC 14,669 7 Cities Ballroom 4,108 800-Flowers, Inc. 654 A J & L Corporation 9,495 A Logo For You 11,923 A Relaxing Escape 13,285 A. Carroll's Bistro 7,427 A. Foster Higgins & Co., Inc. 6,337 AA Conscientious Carpet Care 17,911 Ms. Katherine N. Aanestad 6,604 Mr. and Mrs. Dennis Abbott 9,988 Mrs. Elaine H. Abbott Mr. Henry Mook 818 Dr. Paul Jerome Abbott Mrs. Jan Laberteaux Abbott 18,544 Mr. David Abbou 5,231 Stephen Martin Abdella, Esq. Mrs. Ann Morse Abdella 2,947 Mrs. Susan Van Volkenburgh Abdella 4,506 Mr. and Mrs. Samir J. Abdennour 463 Dr. Diane D. Abdo Dr. Robert John Abdo 13,286 Ms. Thomasina Abdoe 3,383 Mr. Maziar Abdolrasulnia 5,990 Mr. Rasul Abdolrasulnia 14,877 Mr. Khalil Abdul-Malik 12,256 Mr. Mikal Tahron Abdul-Saboor 201 Aberdeen Barn 899 Ms. Patricia Ann Abernathy 16,469 Ms. Valerie G. Abernathy 9,991 Abington Recorder Society 9,213 Mr. Alfred Ellis Abiouness Mrs. Kay Whitley Abiouness 13,287 Ms. Billie Abney 9,753 Mr. and Mrs. Richard L. Abood 9,127 Mr. Aaron B. Abraham Ms. Lauren Abraham 14,878 Mr. and Mrs. Reuben Abraham 5,065 Mr. Lehn Abrams Ms. Pamela F. Abrams 7,421 William and Judith Abrams 7,792 Mr. Nicolas Alejandro Abrigo 17,912 Mrs. -

Creativity, Wisdom, and Our Evolutionary Future

ARTICLE .19 Creativity, Wisdom, and Our Evolutionary Future Thomas Lombardo Center for Future Consciousness USA Abstract In this paper I develop an integrative theoretical framework for understanding creativity, synthesizing themes and principles derived from mythology and philosophy, the physical and biological sciences, psycholo- gy, social and economic history, technology, and art and the study of beauty. I demonstrate how the creative process is integral to natural and human evolution and how human creativity builds upon creative evolution in nature. Further, I describe the relationship between creativity and both heightened future consciousness and wisdom, arguing that the latter two capacities clearly embody a creative dimension and form the leading edge of the future evolution of the human mind. Keywords: Creativity, creation, mythology, evolution, psychology, Gestalt, holism, technology, beauty, future consciousness, wisdom, self-organization, order and chaos, complexity Introduction "The ultimate metaphysical ground is the creative advance into novelty". Alfred North Whitehead In this paper I develop an integrative theoretical framework for understanding creativity, syn- thesizing themes and principles derived from mythology and philosophy, the physical and biologi- cal sciences, psychology, social and economic history, technology, and art and the study of beauty. I demonstrate how the creative process is integral to natural and human evolution and how human creativity builds upon creative evolution in nature. Further, I describe the relationship between cre- ativity and both heightened future consciousness and wisdom, arguing that the latter two capacities clearly embody a creative dimension and form the leading edge of the future evolution of the human mind. Journal of Futures Studies, September 2011, 16(1): 19 - 46 Journal of Futures Studies The theoretical framework presented is ontologically balanced, incorporating both the mental and physical sides of the creative process, and addressing both individual and collective dimensions within creativity.