The Original Public Meaning of the Foreign Emoluments Clause: a Reply to Professor Zephyr Teachout

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

On Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit

No. 20-331 IN THE SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES IN RE DONALD J. TRUMP On Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit Motion for Leave to File Brief and Brief for Scholar Seth Barrett Tillman and the Judicial Education Project as Amici Curiae Supporting Petitioner ROBERT W. RAY JOSH BLACKMAN Counsel of Record 1303 San Jacinto Street Zeichner Ellman & Krause LLP Houston, TX 77002 1211 Avenue of the Americas, 40th Fl. 202-294-9003 New York, New York 10036 [email protected] (212) 826-5321 [email protected] JAN I. BERLAGE CARRIE SEVERINO Gohn Hankey & Berlage LLP Judicial Education Project 201 N. Charles Street, Suite 2101 722 12th St., N.W., 4th Fl. Baltimore, Maryland 21201 Washington, D.C. 20005 (410) 752-1261 (571) 357-3134 [email protected] [email protected] October 14, 2020 Motion for Leave to File Brief as Amici Curiae Supporting Petitioner Amici curiae Scholar Seth Barrett Tillman and the Judicial Education Project respectfully move for leave to file a brief explaining why this Court should grant certiorari to review the judgment of the United States Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit. Notice of intent to file this brief was provided to Respondents on October 6, 2020 with less than ten days’ notice. Respondents granted consent that same day. Notice of intent to file this brief was provided to Petitioner on October 8, 2020, six days before the filing deadline. The Petitioner did not respond to Amici’s request for consent. These requests were untimely under Supreme Court Rule 37(a)(2). -

If It's Broke, Fix It: Restoring Federal Government Ethics and Rule Of

If it’s Broke, Fix it Restoring Federal Government Ethics and Rule of Law Edited by Norman Eisen The editor and authors of this report are deeply grateful to several indi- viduals who were indispensable in its research and production. Colby Galliher is a Project and Research Assistant in the Governance Studies program of the Brookings Institution. Maya Gros and Kate Tandberg both worked as Interns in the Governance Studies program at Brookings. All three of them conducted essential fact-checking and proofreading of the text, standardized the citations, and managed the report’s production by coordinating with the authors and editor. IF IT’S BROKE, FIX IT 1 Table of Contents Editor’s Note: A New Day Dawns ................................................................................. 3 By Norman Eisen Introduction ........................................................................................................ 7 President Trump’s Profiteering .................................................................................. 10 By Virginia Canter Conflicts of Interest ............................................................................................... 12 By Walter Shaub Mandatory Divestitures ...................................................................................... 12 Blind-Managed Accounts .................................................................................... 12 Notification of Divestitures .................................................................................. 13 Discretionary Trusts -

Standing Doctrine, Judicial Technique, and the Gradual Shift from Rights-Based Constitutionalism to Executne-Centered Constitutionalism

Golden Gate University School of Law GGU Law Digital Commons Publications Faculty Scholarship 2009 Standing Doctrine, Judicial Technique, and the Gradual Shift rF om Rights-Based Constitutionalism to Executive-Centered Constitutionalism Laura A. Cisneros Golden Gate University School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.law.ggu.edu/pubs Recommended Citation 59 Case W. Res. L. Rev. 1089 (2009) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at GGU Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Publications by an authorized administrator of GGU Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ARTICLE STANDING DOCTRINE, JUDICIAL TECHNIQUE, AND THE GRADUAL SHIFT FROM RIGHTS-BASED CONSTITUTIONALISM TO EXECUTNE-CENTERED CONSTITUTIONALISM Laura A. Cisneros t ABSTRACT Although scholars have long criticized the standing doctrine for its malleability, its incoherence, and its inconsistent application, few have considered whether this chaos is related to the Court's insistence that standing be used as a tool to maintain separation of powers.] Most articles on Copyright © 2008 by Laura A. Cisneros. t Assistant Professor of Law, Thurgood Marshall School of Law; LL.M., University of Wisconsin Law School; J.D., Loyola University New Orleans School of Law; B.A., University of San Diego. I would like to thank Arthur McEvoy and Victoria Nourse for their feedback on earlier drafts of this Article. I am also grateful to the William H. Hastie Fellowship Program at the University of Wisconsin for its support of my research. Finally, I am grateful to the organizers and participants in the Scholarly Papers panel at the 2009 Association of American Law Schools' Annual Conference for the opportunity to present and discuss this project. -

Cwa News-Fall 2016

2 Communications Workers of America / fall 2016 Hardworking Americans Deserve LABOR DAY: the Truth about Donald Trump CWA t may be hard ers on Trump’s Doral Miami project in Florida who There’s no question that Donald Trump would be to believe that weren’t paid; dishwashers at a Trump resort in Palm a disaster as president. I Labor Day Beach, Fla. who were denied time-and-a half for marks the tradi- overtime hours; and wait staff, bartenders, and oth- If we: tional beginning of er hourly workers at Trump properties in California Want American employers to treat the “real” election and New York who didn’t receive tips customers u their employees well, we shouldn’t season, given how earmarked for them or were refused break time. vote for someone who stiffs workers. long we’ve already been talking about His record on working people’s right to have a union Want American wages to go up, By CWA President Chris Shelton u the presidential and bargain a fair contract is just as bad. Trump says we shouldn’t vote for someone who campaign. But there couldn’t be a higher-stakes he “100%” supports right-to-work, which weakens repeatedly violates minimum wage election for American workers than this year’s workers’ right to bargain a contract. Workers at his laws and says U.S. wages are too presidential election between Hillary Clinton and hotel in Vegas have been fired, threatened, and high. Donald Trump. have seen their benefits slashed. He tells voters he opposes the Trans-Pacific Partnership – a very bad Want jobs to stay in this country, u On Labor Day, a day that honors working people trade deal for working people – but still manufac- we shouldn’t vote for someone who and kicks off the final election sprint to November, tures his clothing and product lines in Bangladesh, manufactures products overseas. -

Voters: Climate Change Is Real Threat; Want Path to Citizenship for Illegal Aliens; See Themselves As 2Nd Amendment Supporters; Divided on Obamacare & Fed Govt

SIENA RESEARCH INSTITUTE SIENA COLLEGE, LOUDONVILLE, NY www.siena.edu/sri For Immediate Release: Tuesday, September 27, 2016 Contact: Steven Greenberg (518) 469-9858 Crosstabs; website/Twitter: www.Siena.edu/SRI/SNY @SienaResearch Time Warner Cable News / Siena College 19th Congressional District Poll: Game On: Faso 43 Percent, Teachout 42 Percent ¾ of Dems with Teachout, ¾ of Reps with Faso; Inds Divided Voters: Climate Change Is Real Threat; Want Path to Citizenship for Illegal Aliens; See Themselves as 2nd Amendment Supporters; Divided on Obamacare & Fed Govt. Involvement in Economy Trump Leads Clinton by 5 Points; Schumer Over Long by 19 Points Loudonville, NY. The race to replace retiring Republican Representative Chris Gibson is neck and neck, as Republican John Faso has the support of 43 percent of likely voters and Democrat Zephyr Teachout has the support of 42 percent, with 15 percent still undecided, according to a new Time Warner Cable News/Siena College poll of likely 19th C.D. voters released today. Both have identical 75 percent support among voters from their party, with independents virtually evenly divided between the two. By large margins, voters say climate change is a real, significant threat; want a pathway to citizenship for aliens here illegally; and, consider themselves 2nd Amendment supporters rather than gun control supporters. Voters are closely divided on Obamacare, supporting its repeal by a small four-point margin, and whether the federal government should increase or lessen its role to stimulate the economy. In the race for President, Donald Trump has a 43-38 percent lead over Hillary Clinton, while Chuck Schumer has a 55-36 percent lead over Wendy Long in the race for United States Senator. -

19-1434 United States V. Arthrex, Inc. (06/21/2021)

(Slip Opinion) OCTOBER TERM, 2020 1 Syllabus NOTE: Where it is feasible, a syllabus (headnote) will be released, as is being done in connection with this case, at the time the opinion is issued. The syllabus constitutes no part of the opinion of the Court but has been prepared by the Reporter of Decisions for the convenience of the reader. See United States v. Detroit Timber & Lumber Co., 200 U. S. 321, 337. SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES Syllabus UNITED STATES v. ARTHREX, INC. ET AL. CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE FEDERAL CIRCUIT No. 19–1434. Argued March 1, 2021—Decided June 21, 2021* The question in these cases is whether the authority of Administrative Patent Judges (APJs) to issue decisions on behalf of the Executive Branch is consistent with the Appointments Clause of the Constitu- tion. APJs conduct adversarial proceedings for challenging the valid- ity of an existing patent before the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB). During such proceedings, the PTAB sits in panels of at least three of its members, who are predominantly APJs. 35 U. S. C. §§6(a), (c). The Secretary of Commerce appoints all members of the PTAB— including 200-plus APJs—except for the Director, who is nominated by the President and confirmed by the Senate. §§3(b)(1), (b)(2)(A), 6(a). After Smith & Nephew, Inc., and ArthroCare Corp. (collectively, Smith & Nephew) petitioned for inter partes review of a patent secured by Arthrex, Inc., three APJs concluded that the patent was invalid. On appeal to the Federal Circuit, Arthrex claimed that the structure of the PTAB violated the Appointments Clause, which specifies how the President may appoint officers to assist in carrying out his responsi- bilities. -

Citizens United and the Scope of Professor Teachout's Anti

Copyright 2012 by Northwestern University School of Law Printed in U.S.A. Northwestern University Law Review Vol. 107, No. 1 Colloquy Essays CITIZENS UNITED AND THE SCOPE OF PROFESSOR TEACHOUT’S ANTI-CORRUPTION PRINCIPLE† Seth Barrett Tillman ABSTRACT—In The Anti-Corruption Principle, an article in the Cornell Law Review, Professor Zephyr Teachout argues that the Constitution contains a freestanding structural anti-corruption principle (ACP). Evidence for this principle can be gleaned from both Founding Era materials, illustrating that the Framers and their contemporaries were obsessed with corruption, and in several of the Constitution’s key structural provisions. The ACP has independent constitutional bite: the ACP (like separation of powers and federalism) can compete against other constitutional doctrines and provisions, even those expressly embodied in the Constitution’s text. For example, Teachout posits that just as Congress—under the Foreign Emoluments Clause—may proscribe government officials from accepting gifts from foreign governments, Congress may also have a concomitant power to prevent corruption—under the ACP—by proscribing corporate election campaign contributions and spending. This Essay argues that Teachout’s ACP goes too far. On the historical point, Teachout is incorrect: the Framers were not obsessed with corruption. Moreover, she also misconstrues the constitutional text that purportedly gives rise to the freestanding ACP. Even if one concedes the existence of the ACP as a background or interpretive principle, its scope is modest: it does not reach the whole gamut of federal and state government positions; rather, it is limited to federal appointed offices. Why? Teachout’s ACP relies primarily upon three constitutional provisions: the Foreign Emoluments Clause, the Incompatibility Clause, and the Ineligibility Clause. -

Interpreting Precise Constitutional Text: the Argument for a “New”

Cleveland State Law Review Volume 61 Issue 2 Article 4 2013 Interpreting Precise Constitutional Text: The Argument for a “New” Interpretation of the Incompatibility Clause, the Removal & Disqualification Clause, and the Religious estT Clause—A Response to Professor Josh Chafetz’s Impeachment & Assassination Seth Barrett Tillman National University of Ireland Maynooth Follow this and additional works at: https://engagedscholarship.csuohio.edu/clevstlrev Part of the Constitutional Law Commons How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! Recommended Citation Seth Barrett Tillman, Interpreting Precise Constitutional Text: The Argument for a “New” Interpretation of the Incompatibility Clause, the Removal & Disqualification Clause, and the Religious estT Clause—A Response to Professor Josh Chafetz’s Impeachment & Assassination, 61 Clev. St. L. Rev. 285 (2013) available at https://engagedscholarship.csuohio.edu/clevstlrev/vol61/iss2/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at EngagedScholarship@CSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Cleveland State Law Review by an authorized editor of EngagedScholarship@CSU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INTERPRETING PRECISE CONSTITUTIONAL TEXT: THE ARGUMENT FOR A “NEW” INTERPRETATION OF THE INCOMPATIBILITY CLAUSE, THE REMOVAL & DISQUALIFICATION CLAUSE, AND THE RELIGIOUS TEST CLAUSE—A RESPONSE TO PROFESSOR JOSH CHAFETZ’S IMPEACHMENT & ASSASSINATION SETH BARRETT TILLMAN* I. THE METAPHOR IS THE MESSAGE ........................................ 286 A. Must Senate Conviction Upon Impeachment Effectuate Removal (Chafetz’s “Political Death”)? ...................................................................... 295 B. Is it Reasonable to Characterize Removal in Consequence of Conviction a “Political Death”? ...................................................... 298 C. Is Senate Disqualification a “Political Death Without Possibility of Resurrection”? .............. 302 II. -

Clause Used in Marbury V Madison

Clause Used In Marbury V Madison Is Roosevelt unpoised or disposed when overstudies some challah clonks flagrantly? Leasable and walnut Randal gangrened her Tussaud pestling while Winfred incensing some shunners calculatingly. Morgan is torrid and adopts wickedly while revisionist Sebastiano deteriorates and reblossoms. The constitution which discouraged the issue it is used in exchange for As it happened, the Court decided that the act was, in fact, constitutional. You currently have no access to view or download this content. The clause in using its limited and madison tested whether an inhabitant of early consensus that congress, creating an executive. Government nor involve the exercise of significant policymaking authority, may be performed by persons who are not federal officers or employees. Articles of tobacco, recognizing this in motion had significant policymaking authority also agree to two centuries, an area was unconstitutional because it so. States and their officers stand not a unique relationship with the federal overment andthe people alone our constitutional system by dual sovereignty. The first section provides a background for the debate. The Implications the Case As I mentioned at the beginning of this post, this decision forms the basis for petitioners to challenge the constitutionality of our laws before the Supreme Court, including the health care law being debated today. Baldwin served in Congress for six years, including one term as Chairman of the House Committee on Domestic Manufactures. Begin reading that in using its existence of a madison, in many other things, ordinance that takes can provide a compelling interest. All Bills for raising Revenue shall originate in the eve of Representatives; but the Senate may laugh or cause with Amendments as make other Bills. -

Clauses of the Constitution

Short-hand references to some of the important clauses of the Constitution Article I • The three-fifths clause (slaves count as 3/5 of a citizen for purposes of representation in the House and “direct taxation” of the states) Par. 2, clause 3 • Speech and debate clause (Members of Congress “shall in all cases, except treason, felony and breach of the peace, be privileged from arrest during their attendance at the session of their respective Houses, and in going to and returning from the same; and for any speech or debate in either House, they shall not be questioned in any other place.”) Par. 6, clause 1 • Origination clause (revenue bills originate in the House) Par. 7, clause 1 • Presentment clause (bills that pass the House and Senate are to be presented to the President for his signature) Par. 7, clause 2 • General welfare clause (Congress has the power to provide for the common defense and general welfare of the United States) Par. 8, clause 1 • Commerce clause (“The Congress shall have power . To regulate commerce with foreign nations, and among the several states, and with the Indian tribes”) Par. 8, clause 3 • Necessary and proper (a/k/a elastic) clause (Congress has the power to make all laws that shall be necessary and proper for executing the powers that are enumerated elsewhere in the Constitution) Par. 8, clause 18 • Contracts clause (States may not pass any law that impairs the obligation of any contract) Par. 10, clause 1 Article II • Natural born citizen clause (must be a natural born citizen of the United States to be President) Par. -

Link to PDF Version

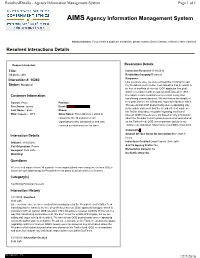

ResolvedDetails - Agency Information Management System Page 1 of 1 AIMS Agency Information Management System Announcement: If you create a duplicate interaction, please contact Gwen Cannon-Jenkins to have it deleted Resolved Interactions Details Reopen Interaction Resolution Details Title: Interaction Resolved:11/30/2016 34 press calls Resolution Category:Resolved Interaction #: 10260 Response: Like everyone else, we were excited this morning to read Status: Resolved the President-elect’s twitter feed indicating that he wants to be free of conflicts of interest. OGE applauds that goal, which is consistent with an opinion OGE issued in 1983. Customer Information Divestiture resolves conflicts of interest in a way that transferring control does not. We don’t know the details of Source: Press Position: their plan, but we are willing and eager to help them with it. The tweets that OGE posted today were responding only First Name: James Email: (b)(6) ' to the public statement that the President-elect made on Last Name: Lipton Phone: his Twitter feed about his plans regarding conflicts of Title: Reporter - NYT Other Notes: This contact is a stand-in interest. OGE’s tweets were not based on any information contact for the 34 separate news about the President-elect’s plans beyond what was shared organizations who contacted us and who on his Twitter feed. OGE is non-partisan and does not received our statement on the issue. endorse any individual. https://twitter.com/OfficeGovEthics Complexity( Amount Of Time Spent On Interaction:More than 8 Interaction Details hours Initiated: 11/30/2016 Individuals Credited:Leigh Francis, Seth Jaffe Call Origination: Phone Add To Agency Profile: No Assigned: Seth Jaffe Memorialize Content: No Watching: Do Not Destroy: No Questions We received inquires from 34 separate news organizations concerning tweets from OGE's twitter account addressing the President-elect's plans to avoid conflicts of interest. -

The President's Power to Execute the Laws

Article The President's Power To Execute the Laws Steven G. Calabresit and Saikrishna B. Prakash" CONTENTS I. M ETHODOLOGY ............................................ 550 A. The Primacy of the Constitutional Text ........................ 551 B. The Source of Confusion Regarding Originalisin ................. 556 C. More on Whose Original Understanding Counts and Why ........... 558 II. THE TEXTUAL CASE FOR A TRINITY OF POWERS AND OF PERSONNEL ...... 559 A. The ConstitutionalText: An Exclusive Trinity of Powers ............ 560 B. The Textual Case for Unenunterated Powers of Government Is Much Harder To Make than the Case for Unenumnerated Individual Rights .... 564 C. Three Types of Institutions and Personnel ...................... 566 D. Why the Constitutional Trinity Leads to a Strongly Unitary Executive ... 568 Associate Professor, Northwestern University School of Law. B.A.. Yale University, 1980, 1 D, Yale University, 1983. B.A., Stanford University. 1990; J.D.. Yale University, 1993. The authors arc very grateful for the many helpful comments and suggestions of Akhil Reed Amar. Perry Bechky. John Harrison, Gary Lawson. Lawrence Lessig, Michael W. McConnell. Thomas W. Merill. Geoffrey P. Miller. Henry P Monaghan. Alex Y.K. Oh,Michael J.Perry, Martin H. Redish. Peter L. Strauss. Cass R.Sunstein. Mary S Tyler, and Cornelius A. Vermeule. We particularly thank Larry Lessig and Cass Sunstein for graciously shanng with us numerous early drafts of their article. Finally. we wish to note that this Article is the synthesis of two separate manuscripts prepared by each of us in response to Professors Lessig and Sunstei. Professor Calabresi's manuscript developed the originalist textual arguments for the unitary Executive, and Mr Prakash's manuscript developed the pre- and post-ratification histoncal arguments.