Joint Submission Parliamentary Inquiry Into

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![[2014] Nzhc 124 Between Intercity Group (Nz)](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7840/2014-nzhc-124-between-intercity-group-nz-777840.webp)

[2014] Nzhc 124 Between Intercity Group (Nz)

IN THE HIGH COURT OF NEW ZEALAND AUCKLAND REGISTRY CIV-2012-404-007532 [2014] NZHC 124 INTERCITY GROUP (NZ) LIMITED BETWEEN Plaintiff AND NAKEDBUS NZ LIMITED Defendant Hearing: 25 - 29 November 2013 Counsel: JD McBride and PT Hall for Plaintiff MC Harris and BA Tompkins for Defendant Judgment: 12 February 2014 JUDGMENT OF ASHER J This judgment was delivered by me on Wednesday, 12 February 2014 at 11.00 am pursuant to r 11.5 of the High Court Rules. Registrar/Deputy Registrar Solicitors/Counsel: Simpson Western Lawyers, Auckland. Gilbert Walker, Auckland. JD McBride, Auckland. Table of Contents Para No Two fierce competitors [1] The use of the words “inter city” [10] The ICG claims [21] The first cause of action – the breach of undertaking [29] The second cause of action – the use by Nakedbus of keywords in Google’s AdWord service [37] How Google operates [41] Nakedbus’ use of the words “inter city” on Google [53] The use of keywords by Nakedbus and s 89(2) – the different positions of the parties [61] Keywords and s 89(2) [67] Use [73] Clean hands [89] The third cause of action – the use by Nakedbus of the words “inter city” in their advertisements and website [94] The words “intercity” and “inter city” [100] The s 89(2) threshold – the use of the word “intercity” in New Zealand [103] The appearance of “inter city” in the advertisements [131] Section 89(2) and deliberate “use” [135] Section 89(2) – “likely to be taken as used” [155] The word “identical” in s 89(1)(a) [172] Are the words identical with the registered trade mark “INTERCITY”? [182] Are the words similar to the registered trade mark “INTERCITY”? [185] Likely to deceive or confuse [190] Honest use [207] Conclusion on the third cause of action [212] The fourth cause of action – passing off [213] The fifth cause of action – breach of the Fair Trading Act [219] Summary [228] Result [234] Two fierce competitors [1] InterCity Group (NZ) Ltd (ICG) operates a long distance national passenger bus network under the brand name “InterCity”. -

Rotorua & the Bay of Plenty

©Lonely Planet Publications Pty Ltd Rotorua & the Bay of Plenty Includes ¨ Why Go? Rotorua . 279 Captain Cook christened the Bay of Plenty when he cruised Around Rotorua . 294 past in 1769, and plentiful it remains. Blessed with sunshine Tauranga . 298 and sand, the bay stretches from Waihi Beach in the west to Opotiki in the east, with the holiday hubs of Tauranga, Mt Mt Maunganui . 304 Maunganui and Whakatane in between. Katikati . 308 Offshore from Whakatane is New Zealand’s most active Maketu . 309 volcano, Whakaari (White Island). Volcanic activity defines Whakatane . 310 this region, and nowhere is this subterranean spectacle Ohope . 315 more obvious than in Rotorua. Here the daily business of life goes on among steaming hot springs, explosive geysers, Opotiki . 317 bubbling mud pools and the billows of sulphurous gas re- sponsible for the town’s ‘unique’ eggy smell. Rotorua and the Bay of Plenty are also strongholds of Best Places to Eat Māori tradition, presenting numerous opportunities to ¨ Macau (p302) engage with NZ’s rich indigenous culture: check out a power-packed concert performance, chow down at a hangi ¨ Elizabeth Cafe & Larder (Māori feast) or skill-up with some Māori arts-and-crafts (p302) techniques. ¨ Post Bank (p307) ¨ Abracadabra Cafe Bar (p291) When to Go ¨ Sabroso (p292) ¨ The Bay of Plenty is one of NZ’s sunniest regions: Whakatane records a brilliant 2350 average hours of sunshine per year! In summer (December to February) Best Places to maximums hover between 20°C and 27°C. Everyone else is Sleep here, too, but the holiday vibe is heady. -

Insight Article Print Format :: BUDDLEFINDLAY

The naked(bus) truth - using trade marks as keywords Hamish Selby 25 August 2014 There is little doubt that Google AdWords (and the careful selection of keywords) can be a powerful tool to increase online business and provide a competitive edge for businesses. However, what limits trade mark law places on the selection and use of third party trade marks as keywords is still uncertain in New Zealand and Australia as there have been no cases directly decided on this point. In February this year, some certainty was finally provided (at least in New Zealand) with the help of a case involving Nakedbus. The High Court of New Zealand issued a decision about the unauthorised use of trade marks as keywords in connection with Google AdWords (Intercity Group (NZ) Ltd v. Nakedbus NZ Ltd [2014] NZHC 124 (Feb. 12, 2014)). Incidentally, this was also New Zealand’s first substantive decision regarding Google AdWords and the use of keywords. The case involved two of New Zealand's largest long-distance bus companies, InterCity and Nakedbus. InterCity (the successor of the former New Zealand Railway Corporations' bus services) had traded in a near monopoly position. In 2006, Nakedbus was founded to directly challenge InterCity's dominant position in the New Zealand market. From its launch, Nakedbus pushed the envelope by using the words "inter city" in their advertising to attract customers and take market share from InterCity. A battle ensued between the parties for the next few years, which reached fever pitch in 2012 when Nakedbus embarked upon a major Google AdWords campaign. -

Public Transport Timetable for Bookings Phone 07-888-7260

Public Transport Timetable For Bookings Phone 07-888-7260 PLEASE NOTE: Bus Services can change without notice at any time. Current as of: 1st October 2016 Matamata to Cambridge Cambridge to Matamata Company Departs Changes Arrives Company Departs Changes Arrives Intercity 8:20am 0 8:50am ManaBus 9:40am 0 10:15am ManaBus 8:20am 0 8:55am Intercity 12:30pm 0 1:00pm Intercity 3:50pm 0 4:30pm Intercity 7:00pm 0 7:30pm ManaBus 6:05pm 0 6:40pm ManaBus 8:10pm 0 8:45pm Matamata to Hamilton Hamilton to Matamata Company Departs Changes Arrives Company Departs Changes Arrives Intercity 8:20am 0 9:20am ManaBus 9:15am 0 10:15am ManaBus 8:20am 0 9:20am Intercity 10:15am 0 11:15am Intercity 3:50pm 0 5:00pm Intercity 12:00pm 0 1:00pm Intercity 4:50pm 0 5:55pm Intercity 3:10pm 0 4:10pm ManaBus 6:05pm 0 7:10pm Intercity 6:30pm 0 7:30pm ManaBus 7:45pm 0 8:45pm Matamata to Bombay Bombay to Matamata Company Departs Changes Arrives Company Departs Changes Arrives Intercity 8:20am 1 10:40am Intercity 8:50am 0 11:15am Intercity 4:50pm 0 7:10pm Intercity 10:20am 1 1:00pm Intercity 1:40pm 0 4:10pm Intercity 4:25pm 1 7:30pm Matamata to Manukau City Manukau City to Matamata Company Departs Changes Arrives Company Departs Changes Arrives ManaBus 8:20am 0 11.15am ManaBus 7:35am 0 10:15am Intercity 8:20am 1 11:10am Intercity 8:20am 0 11:15am Intercity 3:50pm 1 6:55pm Intercity 9:50am 1 1:00pm Intercity 4:50pm 0 7:30pm Intercity 1:05pm 0 4:10pm ManaBus 6:05pm 0 8:45pm Intercity 4:00pm 1 7:30pm ManaBus 6:15pm 8:45pm Matamata to Auckland Auckland to Matamata Company Departs Changes Arrives Company Departs Changes Arrives ManaBus 8:20am 0 11:30am ManaBus 7:00am 0 10:15am Intercity 8:20am 1 11.40am Intercity 8:00am 0 11:15am Intercity 3:50pm 1 7:30pm Intercity 9:30am 1 1:00pm Intercity 4:50pm 0 8:00pm Intercity 12:45pm 0 4:10pm ManaBus 6:05pm 0 9.15pm Intercity 3:30pm 1 7:30pm ManaBus 5:30pm 0 8:45pm Buses do not have a set rate and all prices vary. -

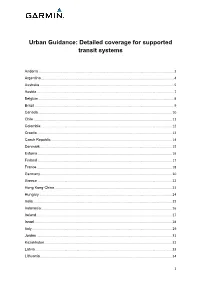

Urban Guidance: Detailed Coverage for Supported Transit Systems

Urban Guidance: Detailed coverage for supported transit systems Andorra .................................................................................................................................................. 3 Argentina ............................................................................................................................................... 4 Australia ................................................................................................................................................. 5 Austria .................................................................................................................................................... 7 Belgium .................................................................................................................................................. 8 Brazil ...................................................................................................................................................... 9 Canada ................................................................................................................................................ 10 Chile ..................................................................................................................................................... 11 Colombia .............................................................................................................................................. 12 Croatia ................................................................................................................................................. -

Monthly Business Report

MONTHLY BUSINESS REPORT October 2009 CONTRIBUTION LIST The following is a list of Business Unit Managers responsible for providing detailed monthly reports. Business Unit Name Customer Services Mark Lambert Project Delivery Allen Bufton Strategy and Planning Peter Clark Marketing and Communications Shelley Watson Corporate Services Stephen Smith TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 CUSTOMER SERVICES ............................................ ERROR! BOOKMARK NOT DEFINED. 1.1. PASSENGER TRANSPORT PATRONAGE – NETWORK WIDE ................................... ERROR! BOOKMARK NOT DEFINED. 1.2. MAJOR INFRASTRUCTURE WORKS ................................................................................................................................. 12 1.3. SPECIAL EVENT PASSENGER TRANSPORT SERVICES ................................................................................................. 12 1.4. REGISTERED SERVICE NOTIFICATIONS RECEIVED BY ARTA UNDER THE PUBLIC TRANSPORT MANAGEMENT ACT 2008 ................................................................................................................................................... 12 1.5. PUBLIC TRANSPORT CONCESSIONARY FARE SCHEME (CFS) ................................................................................... 14 1.6. AUCKLAND TOTAL MOBILITY SCHEME ........................................................................................................................ 14 1.7. TRAVEL PLANNING ........................................................................................................................................................... -

Bus Transportation 2016 Season Booking Form

BUS TRANSPORTATION 2016 SEASON BOOKING FORM The NZSO is pleased to once again offer a bus service to select NZSO concerts in our subscription centres for the 2016 season. BUS SERVICE DETAILS DEPARTURE TIME BUS SERVICE PICK-UP POINTS CONCERT DAYS BUS PRICE (BEFORE CONCERT) TIMARU – CHRISTCHURCH Pak’n’Save car park, Evans Street, Timaru 3 hours All Christchurch concerts $29 Café Mes Amis (Orari Café), Orari 2 hours, 30 mins Ashburton Hotel Carpark 1 hour, 50 mins OAMARU – DUNEDIN Pearsons Bus Depot, 4 Regina Lane, Oamaru 2 hours, 30 mins All Dunedin concerts $24 Hampden Motors, Cnr London and Lincoln Streets, Hampden 2 hours De Rail Café, 32 Sanday Street, Palmerston 1.5 hours MASTERTON – WELLINGTON Tranzit Bus Depot, 316 Queens Street, Masterton 3 hours, 15 mins All Friday Wellington $35 concerts New World (bus stop opposite), Carterton 2 hours, 30 mins Greytown Central Bus Stop, 77 Main Street 2 hours, 20 mins Featherston Mobil Service Station 2 hours, 10 mins WAIKANAE – WELLINGTON Newmans bus stop Countdown, Waikanae 2 hours All concerts $24 Paraparaumu Library, Rimu Road 1 hour, 45 mins Old Hotel Site, Paekakariki 1 hour, 35 mins Pedestrian Overpass, James Street, Plimmertson 1 hour, 20 min Bus stop next to Prestige Caravans, Mana 1 hour, 15 minutes Tawa Mall 1 hour, 5 mins LEVIN – WELLINGTON Opposite railway - Levin 2 hours, 30 mins Friday Wellington concerts $30 Intercity bus stop – Otaki TAURANGA – HAMILTON i-Site (wait on opposite side), Wharf Street, Tauranga 2 hours, 45 mins Only available on some $35 Hamilton concert dates i-Site, -

Tourism and Transport in New Zealand

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Lincoln University Research Archive Tourism and Transport in New Zealand Susanne Becken PhD Student Environment Society and Design Division Lincoln University [email protected] July 2001 ISSN 1175-5385 Tourism Recreation Research and Education Centre (TRREC) Report No. 54 Tourism and Transport in New Zealand – Implications for Energy use Source of advertisement: www.purenz.com TRREC Discussion Paper July 2002 Susanne Becken [email protected] This discussion paper is part of a PhD project on energy use in the New Zealand tourism sector. The research is supported by Non Specific Output Funding of Landcare Research New Zealand Ltd and the Human Sciences Division at Lincoln University through the supervision of Prof. David Simmons. Contents Contents....................................................................................................................................... i List of Tables.............................................................................................................................iii List of Figures ...........................................................................................................................iii Equation ....................................................................................................................................iii Chapter 1 Introduction.................................................................................................... 1 Chapter 2 Transport -

Keith's Itinerary for Travel from Home to Jonny's and Return from 9Th to the 12Th of March 2018 Friday 9Th March 2018 – De

Keith’s itinerary for travel from Home to Jonny’s and return from 9th to the 12th of March 2018 Friday 9th March 2018 – Depart Home at 10:40 a.m. – Arrive Jonny’s at 2:20 p.m. Arrive / Location Time Service Fare Depart Depart Home Bus Stop 10:43 a.m. Suburban Bus Service 31 Free Arrive PN Main Bus Terminal 10:55 a.m. Depart PN Main Bus Terminal 11:20 a.m. Intercity $26.00 Arrive Wellington Railway Station 1:25 p.m. Depart Wellington Railway Station 1:35 p.m. MetLink Suburban Unit Free Arrive Petone Railway Station 1:47 p.m. Depart Petone Railway Station 2:00 p.m. MetLink Bus Service 150 Free Arrive Jonny’s 2:17 p.m. Monday 12th March 2018 – Depart Jonny’s at 12:20 p.m. – Arrive Home at 4:30 p.m. Arrive / Location Time Service Fare Depart Depart Jonny’s 12:29 p.m. MetLink Bus Service 150 Free Arrive Petone railway Station 12:50 p.m. Depart Petone Railway Station 1:03 p.m. MetLink Suburban Unit Free Arrive Wellington Railway Station 1:15 p.m. Depart Wellington Railway Station 2:00 p.m. Intercity $26.00 Arrive PN Main Bus Terminal 4:10 p.m. Depart PN Main Bus Terminal 4:20 p.m. Suburban Bus Service 32 $1.80 Arrive Home Bus Stop 4:26 p.m. Booking Reference 1017C31 Booking Confirmation Name: Mr Keith Clifford Rewards No: 2087061 Your Itinerary Palmerston North > Wellington - Central on Fri 09 Mar 2018 Service IC6961 Departs Arrives 1 Passenger Palmerston North at 11:20am Wellington - Central at 1:25pm 1 x Standard Gold Next to the Palmerston North i-SITE Railway Station, Platform 9 inside The Square carpark, Bays 1 through 5 Travelling on InterCity IC6961 Napier - Wellington Duration: 02Hr 05min > Please be at your stop at least 15 minutes before departure, and report to the driver before boarding. -

Investment Review 2016 SOUTER INVESTMENTS IS the INVESTMENT OFFICE of the SOUTER FAMILY

Investment Review 2016 SOUTER INVESTMENTS IS THE INVESTMENT OFFICE OF THE SOUTER FAMILY ir Brian Souter co-founded Stagecoach Group plc as a start-up in 1980. Today the company is a leading international transport group, with extensive operations in the UK, United States and Canada, S employing around 40,000 people and operating nearly 11,000 buses and 2,300 daily rail services. Stagecoach floated in 1993 and is listed in the FTSE 250. Sir Brian is Chairman of the company, having stepped down from his role as Chief Executive Officer four years ago. When Sir Brian founded Souter Investments in 2006, more than two thirds of his portfolio was represented by his Stagecoach shareholding, with the remainder invested in a diverse number of managed funds, and a smaller portfolio of unquoted and property investments. Private equity focus Today the balance is very different. Our primary focus is on unquoted investments, and whilst Stagecoach is still a major part of the portfolio it now only represents 34% of total assets. We are sector agnostic, and invest across a wide range of industries, including financial and business services, consumer goods, healthcare, telecoms and industrials. Although not our primary focus, transport will always be an area of interest given Sir Brian’s background. Together our unquoted companies have a turnover of almost £2bn and employ over 19,000 people worldwide. A professional but flexible Our team investment approach The Souter Investments team encompasses a mix We employ high standards of professional of investment professionals and support staff, with diligence and rigour in selecting, executing and offices in Edinburgh and Perth. -

Update of the Otago Southland Regional Land Transport Plans 2015-2021

2018 update of the Otago Southland Regional Land Transport Plans 2015-2021 Otago and Southland RTC Chairs’ foreword The Otago and Southland Regional Transport Committees (RTCs) are pleased to present this mid-term update of the 2015-2021 Otago Southland Regional Land Transport Plans (RLTPs). These plans set our vision of transport in the future and how we - the 10 local authorities in our two regions and the NZ Transport Agency (NZTA) - intend to achieve this by funding and providing transport services and infrastructure, and by concentrating over the next few years on achieving a safer and more sustainable transport system that supports and enhances regional development. Covering almost half of the South Island, the Otago and Southland regions share opportunities to improve transport and face common challenges. These shared issues and opportunities led us to jointly develop our Regional Land Transport Plans. The prosperity of both Otago and Southland, and our quality of life, depends heavily on good land transport infrastructure and services. Our primary industries drive much of the area’s economic growth, so good access and freight services linking farms and forests, suppliers, processors and export gateways are critical. Tourism, another major economic driver in Otago and Southland, also depends on quality road links. Our common challenges include a very large land area and road network but comparatively low rating population in many areas. For the majority of our two regions, the major emphasis in these plans needs to be on maintaining and operating the roading networks, in most cases to existing levels of service. Providing funds to keep the network at similar levels of service to those that exist today is a major challenge. -

Annual Report

G25 Annual Report Tourism New Zealand 2016/2017 Sara Orme 2.64 53,000 million Australian and British visitors followers on during the British and Irish Lions Rugby Tour Facebook 13% more visitors during spring and autumn 10,679 stories generated (estimated value: $227.2 million) 6.3 85 bids million supported through the referrals to tourism Conference Assistance Programme businesses from (estimated value: newzealand.com $164 million) 3.6 million visitors 41 396 million media outlets hosted visits to in 180 visits newzealand.com Miles Holden 40 major trade events 42% increase in premium attended by visitor spend Tourism New Zealand 96% of Kiwis agree or strongly agree that international tourism is good for New Zealand $10.25 6000 billion people surveyed for our partnership campaign with the contributed to the Department of Conservation New Zealand economy by (launching in FY18) international visitors 4,607 100% Pure New Zealand Specialists 181 $3,800 incentive conference average holiday spend bids supported per holiday arrival Adam Bryce Contents 02. Tourism New Zealand — Who We Are 04. Chair and Chief Executive Report 10. Governance 12. Board Members 16. Core Leadership Team 18. Strategic Priorities and Outcomes 29. Statement of Performance 40. Equal Employment Opportunities 45. Financial Statements 50. Notes to the Financial Statements 76. Independent Auditor’s Report 1 London Seoul Beijing* Tokyo New Delhi* Shanghai Guangzhou Mumbai Singapore Jakarta Sydney Tourism New Zealand — Who We Are Tourism New Zealand is the Government organisation responsible for promoting New Zealand to the world and encouraging international visitors to this amazing country. Tourism New Zealand was established in 1991 as a Crown Entity by the New Zealand Tourism Board Act, and since then our staff has worked tirelessly to create award winning campaigns marketing New Zealand as an international visitor destination.