Network-Oriented Public Transport Planning in Medium and Small New Zealand Cities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Report Te Pūrongo Ā-Tau

Annual Report Te Pūrongo ā-Tau CCS Disability Action Manawatu/Horowhenua Inc 2018/19 In an ever-changing world, the focus of CCS Disability Action continues to be one of positive social change. This can be from actions as straightforward as getting our language right to recognising and sponsoring disabled leadership, advocating for physical community change or supporting positive action that showcases the value of all New Zealand citizens. Contents Local Advisory Committee report 3 Local Executive Committee report 4 Regional Representative’s report 5 General Manager’s report 6 Our services 7 Our stories 9 Financial summary 12 Our people 15 Our supporters 16 Discover the difference we make in people’s lives across the region. Get in touch Manawatu/Horowhenua (06) 357 2119 or 0800 227 2255 @ [email protected] 248 Broadway Avenue, Palmerston North 4414 PO Box 143, Palmerston North 4440 www.Facebook.com/ccsDisabilityAction www.Twitter.com/ccsDisabilityA http://nz.linkedin.com/company/ccs-disability-action www.ccsDisabilityAction.org.nz/ Registered Charity Number: CC31190 2 CCS DISABILITY ACTION Local Advisory Committee report Busy and challenging year Kia Ora Koutou, the disabled community on issues that may hinder their accessibility. IT’S MY PLEASURE writing this report on behalf of the Local Advisory Committee We are also hoping we can continue (LAC) of CCS Disability Action Manawatu encourage new members to join the LAC Horowhenua Inc. This past year has been and create a stronger network within extremely busy with the Disability our region. Support Services (DSS) System Transformation pilot up and running I would like acknowledge and thank: in the Mid-Central area since October 2018. -

Agenda of Catchment Operations Committee

I hereby give notice that an Ordinary meeting of the Catchment Operations Committee will be held on: Date: Wednesday, 11 June 2014 Time: 10.00am Venue: Tararua Room Horizons Regional Council 11-15 Victoria Avenue, Palmerston North CATCHMENT OPERATIONS COMMITTEE AGENDA MEMBERSHIP Chair Cr MC Guy Deputy Chair Cr JJ Barrow Councillors Cr LR Burnell, QSM Cr DB Cotton Cr EB Gordon (ex officio) Cr RJ Keedwell Cr PJ Kelly JP Cr GM McKellar Cr DR Pearce Cr PW Rieger QSO JP Cr BE Rollinson Cr CI Sheldon Michael McCartney Chief Executive Contact Telephone: 0508 800 800 Email: [email protected] Postal Address: Private Bag 11025, Palmerston North 4442 Full Agendas are available on Horizons Regional Council website www.horizons.govt.nz Note: The reports contained within this agenda are for consideration and should not be construed as Council policy unless and until adopted. Items in the agenda may be subject to amendment or withdrawal at the meeting. for further information regarding this agenda, please contact: Julie Kennedy, 06 9522 800 CONTACTS 24 hr Freephone : [email protected] www.horizons.govt.nz 0508 800 800 SERVICE Kairanga Marton Taumarunui Woodville CENTRES Cnr Rongotea & Hammond Street 34 Maata Street Cnr Vogel (SH2) & Tay Kairanga-Bunnythorpe Rds, Sts Palmerston North REGIONAL Palmerston North Wanganui HOUSES 11-15 Victoria Avenue 181 Guyton Street DEPOTS Levin Taihape 11 Bruce Road Torere Road Ohotu POSTAL Horizons Regional Council, Private Bag 11025, Manawatu Mail Centre, Palmerston North 4442 ADDRESS FAX 06 9522 929 Catchment -

![[2014] Nzhc 124 Between Intercity Group (Nz)](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7840/2014-nzhc-124-between-intercity-group-nz-777840.webp)

[2014] Nzhc 124 Between Intercity Group (Nz)

IN THE HIGH COURT OF NEW ZEALAND AUCKLAND REGISTRY CIV-2012-404-007532 [2014] NZHC 124 INTERCITY GROUP (NZ) LIMITED BETWEEN Plaintiff AND NAKEDBUS NZ LIMITED Defendant Hearing: 25 - 29 November 2013 Counsel: JD McBride and PT Hall for Plaintiff MC Harris and BA Tompkins for Defendant Judgment: 12 February 2014 JUDGMENT OF ASHER J This judgment was delivered by me on Wednesday, 12 February 2014 at 11.00 am pursuant to r 11.5 of the High Court Rules. Registrar/Deputy Registrar Solicitors/Counsel: Simpson Western Lawyers, Auckland. Gilbert Walker, Auckland. JD McBride, Auckland. Table of Contents Para No Two fierce competitors [1] The use of the words “inter city” [10] The ICG claims [21] The first cause of action – the breach of undertaking [29] The second cause of action – the use by Nakedbus of keywords in Google’s AdWord service [37] How Google operates [41] Nakedbus’ use of the words “inter city” on Google [53] The use of keywords by Nakedbus and s 89(2) – the different positions of the parties [61] Keywords and s 89(2) [67] Use [73] Clean hands [89] The third cause of action – the use by Nakedbus of the words “inter city” in their advertisements and website [94] The words “intercity” and “inter city” [100] The s 89(2) threshold – the use of the word “intercity” in New Zealand [103] The appearance of “inter city” in the advertisements [131] Section 89(2) and deliberate “use” [135] Section 89(2) – “likely to be taken as used” [155] The word “identical” in s 89(1)(a) [172] Are the words identical with the registered trade mark “INTERCITY”? [182] Are the words similar to the registered trade mark “INTERCITY”? [185] Likely to deceive or confuse [190] Honest use [207] Conclusion on the third cause of action [212] The fourth cause of action – passing off [213] The fifth cause of action – breach of the Fair Trading Act [219] Summary [228] Result [234] Two fierce competitors [1] InterCity Group (NZ) Ltd (ICG) operates a long distance national passenger bus network under the brand name “InterCity”. -

Rotorua & the Bay of Plenty

©Lonely Planet Publications Pty Ltd Rotorua & the Bay of Plenty Includes ¨ Why Go? Rotorua . 279 Captain Cook christened the Bay of Plenty when he cruised Around Rotorua . 294 past in 1769, and plentiful it remains. Blessed with sunshine Tauranga . 298 and sand, the bay stretches from Waihi Beach in the west to Opotiki in the east, with the holiday hubs of Tauranga, Mt Mt Maunganui . 304 Maunganui and Whakatane in between. Katikati . 308 Offshore from Whakatane is New Zealand’s most active Maketu . 309 volcano, Whakaari (White Island). Volcanic activity defines Whakatane . 310 this region, and nowhere is this subterranean spectacle Ohope . 315 more obvious than in Rotorua. Here the daily business of life goes on among steaming hot springs, explosive geysers, Opotiki . 317 bubbling mud pools and the billows of sulphurous gas re- sponsible for the town’s ‘unique’ eggy smell. Rotorua and the Bay of Plenty are also strongholds of Best Places to Eat Māori tradition, presenting numerous opportunities to ¨ Macau (p302) engage with NZ’s rich indigenous culture: check out a power-packed concert performance, chow down at a hangi ¨ Elizabeth Cafe & Larder (Māori feast) or skill-up with some Māori arts-and-crafts (p302) techniques. ¨ Post Bank (p307) ¨ Abracadabra Cafe Bar (p291) When to Go ¨ Sabroso (p292) ¨ The Bay of Plenty is one of NZ’s sunniest regions: Whakatane records a brilliant 2350 average hours of sunshine per year! In summer (December to February) Best Places to maximums hover between 20°C and 27°C. Everyone else is Sleep here, too, but the holiday vibe is heady. -

Older Former Drivers' Health, Activity, and Transport in New Zealand

Journal of Transport & Health 14 (2019) 100559 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of Transport & Health journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jth Older former drivers’ health, activity, and transport in New Zealand T ∗ Jean Thatcher Shopea, Dorothy Beggb, Rebecca Brooklandb, a University of Michigan Transportation Research Institute, 2901 Baxter Road, Ann Arbor, MI, 48109, USA b Department of Preventive and Social Medicine, Dunedin School of Medicine, University of Otago, PO Box 56, Dunedin, NZ, New Zealand ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: Objectives: Describe characteristics of New Zealand older adults who are no longer driving - their Ageing health, activity patterns, and mobility/transport practices. Driving Methods: Cross-sectional study of 102 former drivers, recruited from a population-based sample Cessation of community-dwelling older adults (≥65 years), the first wave of an older driver longitudinal Health status study. Licensure Results: Most common reasons for stopping driving were feeling unsafe/uncomfortable or health Transportation issues. Most participants did not plan ahead for driving cessation and travelled by car with family or friends; very few used alternative transport modes. Compared with healthier former drivers, former drivers with poor self-reported health expressed more dissatisfaction with their lives and their ability to get places, were lonelier, and went out less than before they stopped driving. Conclusion: The older New Zealand former drivers studied were mostly female, widowed, and living alone. Very few had planned ahead for driving cessation, and most transport was heavily dependent on private cars driven by others. 1. Introduction In the first three decades of the 21st century, the maturation of the “baby boom” population, combined with increased longevity and declining birth rates, is predicted to transform the developed world's demographics (Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development, 2001). -

Insight Article Print Format :: BUDDLEFINDLAY

The naked(bus) truth - using trade marks as keywords Hamish Selby 25 August 2014 There is little doubt that Google AdWords (and the careful selection of keywords) can be a powerful tool to increase online business and provide a competitive edge for businesses. However, what limits trade mark law places on the selection and use of third party trade marks as keywords is still uncertain in New Zealand and Australia as there have been no cases directly decided on this point. In February this year, some certainty was finally provided (at least in New Zealand) with the help of a case involving Nakedbus. The High Court of New Zealand issued a decision about the unauthorised use of trade marks as keywords in connection with Google AdWords (Intercity Group (NZ) Ltd v. Nakedbus NZ Ltd [2014] NZHC 124 (Feb. 12, 2014)). Incidentally, this was also New Zealand’s first substantive decision regarding Google AdWords and the use of keywords. The case involved two of New Zealand's largest long-distance bus companies, InterCity and Nakedbus. InterCity (the successor of the former New Zealand Railway Corporations' bus services) had traded in a near monopoly position. In 2006, Nakedbus was founded to directly challenge InterCity's dominant position in the New Zealand market. From its launch, Nakedbus pushed the envelope by using the words "inter city" in their advertising to attract customers and take market share from InterCity. A battle ensued between the parties for the next few years, which reached fever pitch in 2012 when Nakedbus embarked upon a major Google AdWords campaign. -

Key Policy Recommendations for Active Transport in New Zealand

Key Policy Recommendations for Active Transport in New Zealand We welcome this Government’s increased focus on 20195 in Dunedin, New Zealand on 13-15 February 2019. wellbeing, walking, cycling, public transport and a Vision Our report is not intended to be a comprehensive and Zero approach. It extends previous efforts to promote active systematic review. Our goal was to establish a set of priority transport in New Zealand, including the National Walking recommendations to guide decision-making in central and and Cycling Strategy (2005),1 a Guide for Decision Makers local government, public health units and regional sports (2008)2 and a Cycling Safety Panel’s action plan (2014).3 trusts in New Zealand and any other organisation that Despite these efforts, rates of active transport in New may have a mandate around transport and environment. Zealand have continued to decline,4 with negative impacts Recognising that some of our recommendations may be on health and the environment. in progress, we urge more rapid implementation in those cases. We need to set ambitious goals and monitor progress to ensure that any changes made are connected and effective. The document outlines key policy recommendations and The Key Policy Recommendations for Active Transport associated actions grouped across four broad categories document is a summary of multi-sectoral discussions held (Figure 1). The full report5 is available on the TALES at The Active Living and Environment Symposium (TALES) Symposium 2019 website.6 A Evaluation, Governance and Funding C Engineering (Infrastructure, Built Environment) A1. Set and monitor shared targets for the proportion of C1. -

Public Transport Timetable for Bookings Phone 07-888-7260

Public Transport Timetable For Bookings Phone 07-888-7260 PLEASE NOTE: Bus Services can change without notice at any time. Current as of: 1st October 2016 Matamata to Cambridge Cambridge to Matamata Company Departs Changes Arrives Company Departs Changes Arrives Intercity 8:20am 0 8:50am ManaBus 9:40am 0 10:15am ManaBus 8:20am 0 8:55am Intercity 12:30pm 0 1:00pm Intercity 3:50pm 0 4:30pm Intercity 7:00pm 0 7:30pm ManaBus 6:05pm 0 6:40pm ManaBus 8:10pm 0 8:45pm Matamata to Hamilton Hamilton to Matamata Company Departs Changes Arrives Company Departs Changes Arrives Intercity 8:20am 0 9:20am ManaBus 9:15am 0 10:15am ManaBus 8:20am 0 9:20am Intercity 10:15am 0 11:15am Intercity 3:50pm 0 5:00pm Intercity 12:00pm 0 1:00pm Intercity 4:50pm 0 5:55pm Intercity 3:10pm 0 4:10pm ManaBus 6:05pm 0 7:10pm Intercity 6:30pm 0 7:30pm ManaBus 7:45pm 0 8:45pm Matamata to Bombay Bombay to Matamata Company Departs Changes Arrives Company Departs Changes Arrives Intercity 8:20am 1 10:40am Intercity 8:50am 0 11:15am Intercity 4:50pm 0 7:10pm Intercity 10:20am 1 1:00pm Intercity 1:40pm 0 4:10pm Intercity 4:25pm 1 7:30pm Matamata to Manukau City Manukau City to Matamata Company Departs Changes Arrives Company Departs Changes Arrives ManaBus 8:20am 0 11.15am ManaBus 7:35am 0 10:15am Intercity 8:20am 1 11:10am Intercity 8:20am 0 11:15am Intercity 3:50pm 1 6:55pm Intercity 9:50am 1 1:00pm Intercity 4:50pm 0 7:30pm Intercity 1:05pm 0 4:10pm ManaBus 6:05pm 0 8:45pm Intercity 4:00pm 1 7:30pm ManaBus 6:15pm 8:45pm Matamata to Auckland Auckland to Matamata Company Departs Changes Arrives Company Departs Changes Arrives ManaBus 8:20am 0 11:30am ManaBus 7:00am 0 10:15am Intercity 8:20am 1 11.40am Intercity 8:00am 0 11:15am Intercity 3:50pm 1 7:30pm Intercity 9:30am 1 1:00pm Intercity 4:50pm 0 8:00pm Intercity 12:45pm 0 4:10pm ManaBus 6:05pm 0 9.15pm Intercity 3:30pm 1 7:30pm ManaBus 5:30pm 0 8:45pm Buses do not have a set rate and all prices vary. -

Accessibility Action Plan

ACCESSIBILITY ACTION PLAN Delivering a transport system which meets the needs of all Aucklanders Version 2: 202 - 2023 < Contents Contents > Overview . 4 Purpose . 6 Accessibility versus Disability . 6 Why does Auckland Transport need an Accessibility Action Plan? . .8 . Objectives . 10 Context . .12 Policy Overview . 14. Auckland Transport Disability policy (2013) . 15 What does Accessibility Look Like? . 15. Action Plan . 18 Actions completed . 20 2021-23 Plan . 23 Auckland Transport internal adoption – making accessibility happen . .25 . Next Steps . 26 Where will we be in three years? . .29 . Appendix 1 - Detailed Policy Context United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (2006) NZ Human Rights Act (1993) NZ Disability Strategy 2016-2026 NZ Disability Strategy – Action Plan (2019) Chief Executives’ Group on Disability Issues (2016) Government Policy Statement on Land Transport 2018 Appendix 2 – Auckland Transport Disability Policy (2013) 2 | Auckland Transport Accessibility Action Plan 2021 - 2023 Auckland Transport Accessibility Action Plan 2021 - 2023 | 3 < Contents Contents > OVERVIEW 4 | Auckland Transport Accessibility Action Plan 2021 - 2023 Auckland Transport Accessibility Action Plan 2021 - 2023 | 5 < Contents Contents > Purpose It is important to note that while we generally Being accessible means that, as far as can The purpose of this document is to mandate talk about people with disabilities as needing reasonably be accommodated, Auckland the actions that Auckland Transport will accessible transport, there are also people Transport ensures that transport facilities, undertake over the next three years to improve whose mobility is impaired, often temporarily, vehicles, information and services are easy to accessibility. This document is an outcome of but who do not fit within a medical definition find out about, to understand, to reach, and to the Auckland Transport Disability Policy (2013), of disability. -

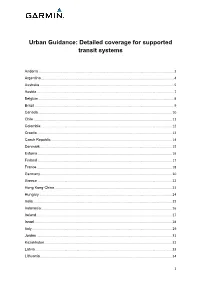

Urban Guidance: Detailed Coverage for Supported Transit Systems

Urban Guidance: Detailed coverage for supported transit systems Andorra .................................................................................................................................................. 3 Argentina ............................................................................................................................................... 4 Australia ................................................................................................................................................. 5 Austria .................................................................................................................................................... 7 Belgium .................................................................................................................................................. 8 Brazil ...................................................................................................................................................... 9 Canada ................................................................................................................................................ 10 Chile ..................................................................................................................................................... 11 Colombia .............................................................................................................................................. 12 Croatia ................................................................................................................................................. -

The New Zealand Public's Readiness for Connected

The New Zealand public’s readiness for connected- and autonomous-vehicles (including driverless), car and ridesharing schemes and the social impacts of these May 2020 NJ Starkey and SG Charlton ISBN 978-1-98-856162-2 (electronic) ISSN 1173-3764 (electronic) NZ Transport Agency Private Bag 6995, Wellington 6141, New Zealand Telephone 64 4 894 5400; facsimile 64 4 894 6100 [email protected] www.nzta.govt.nz Starkey, NJ and SG Charlton (2020) The New Zealand public’s readiness for connected- and autonomous-vehicles (including driverless), car and ridesharing schemes and the social impacts of these. NZ Transport Agency research report 663. 159pp. The School of Psychology, University of Waikato, was contracted by the NZ Transport Agency in 2017 to carry out this research. This publication is copyright © NZ Transport Agency. This copyright work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International licence. You are free to copy, distribute and adapt this work, as long as you attribute the work to the NZ Transport Agency and abide by the other licence terms. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. While you are free to copy, distribute and adapt this work, we would appreciate you notifying us that you have done so. Notifications and enquiries about this work should be made to the Manager Research and Evaluation Programme Team, Research and Analytics Unit, NZ Transport Agency, at [email protected]. Keywords: attitudes, autonomous vehicles, carsharing, connected vehicles, mobility as a service, ridesharing An important note for the reader The NZ Transport Agency is a Crown entity established under the Land Transport Management Act 2003. -

Sociodemographic and Built Environment Associates of Travel to School by Car Among New Zealand Adolescents: Meta-Analysis

International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health Article Sociodemographic and Built Environment Associates of Travel to School by Car among New Zealand Adolescents: Meta-Analysis Sandra Mandic 1,2,3,* , Erika Ikeda 4 , Tom Stewart 5 , Nicholas Garrett 6 , Debbie Hopkins 7 , Jennifer S. Mindell 8 , El Shadan Tautolo 9 and Melody Smith 10 1 School of Sport and Recreation, Faculty of Health and Environmental Sciences, Auckland University of Technology, Private Bag 92006, Auckland 1142, New Zealand 2 Active Living Laboratory, School of Physical Education, Sport and Exercise Sciences, University of Otago, P.O. Box 56, Dunedin 9054, New Zealand 3 Centre for Sustainability, University of Otago, P.O. Box 56, Dunedin 9054, New Zealand 4 MRC Epidemiology Unit, University of Cambridge, Box 285 Institute of Metabolic Science Cambridge Biomedical Campus, Cambridge CB2 0QQ, UK; [email protected] 5 Human Potential Centre, Auckland University of Technology, Private Bag 92006, Auckland 1142, New Zealand; [email protected] 6 Department of Biostatistics and Epidemiology, Faculty of Health and Environmental Sciences, Auckland University of Technology, Private Bag 92006, Auckland 1142, New Zealand; [email protected] 7 Transport Study Unit, School of Geography and the Environment, University of Oxford, South Parks Road, Oxford OX1 3QY, UK; [email protected] 8 Department of Epidemiology and Public Health, UCL (University College London), 1–19 Torrington Place, London WC1E 6BT, UK; [email protected] 9 Pacific