Validity and Reliability of an Objective Test of Cricket Skills

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Indoor Cricket Rules

INDOOR CRICKET RULES THE GAME I. A game is played between two teams, each of a maximum of 8 players II. No team can play with less than 6 players III. The game consists of 2 x 16 over innings IV. The run deduction for a dismissal will be 5 runs V. Each player must bowl 2 overs and bat in a partnership for 4 overs VI. There are 4 partnerships per innings VII. A bowler must not bowl 2 consecutive overs VIII. Batters must change ends at the completion of each over ARRIVAL / LATE PLAYERS A. All teams are to be present at the court allocated for their match to do the toss 2 minutes prior to the scheduled commencement of their game. I Any team failing to arrive on time will forfeit the right to a toss. The non-offending team can choose to field first or wait until the offending team have 6 players present and bat first. II If both teams are late, the first team to have 6 players present automatically wins the toss. B. All forfeits will be declared at the discretion of the duty manager. I Individual players(s) arriving late may take part in the match providing their arrival is before the commencement of the 13 th over of the first innings. II Players who arrive late to field must wait until the end of the over in progress before entering the court. PLAYER SHORT / SUBSTITUTES Player Short a) If a team is 1 player short: When Batting: After 12 overs, the captain of the fielding side will nominate 1 player to bat again in the last 4 overs with the remaining batter. -

Indoor Cricket

Indoor Cricket RULES AND REGULATIONS Indoor Cricket is to be conducted under the Official Rules of Indoor Cricket which are sanctioned by Cricket Australia and the World Indoor Cricket Federation. The following local rules and regulations will apply. Team Requirements 1. The maximum number of players per team is 10, of which 8 can bat and 8 can bowl. 2. If a side is one player short: When batting: After 12 overs, the Captain of the fielding side will nominate one player to bat the last four overs with the remaining batter. When fielding: After 14 overs, the Captain of the batting side must choose two players (must be different players to the player that batted) to bowl the 15th and 16th overs. 3. If a side is two players short: When Batting: As above, except two players chosen will bat four overs each, being the last four overs. When fielding: After 12 overs, the Captain of the batting side must choose two players (must be different players to the players that batted) to bowl the last four overs. 4. If a side has less than 6 players, they must forfeit the game. Game Requirements 1. Games are to commence at 12.45pm. 2. Games will consist of 16 overs per team, 6 balls per over. 3. The batting team bats in pairs with each pair batting for four overs. Upon arrival at the batting crease the batting pair must inform the Umpire of their names. Batters continue batting for the whole four overs whether they are dismissed or not. -

U.S. EPA, Pesticide Product Label, VIGORO WEED & INCT. FERT. 6-IN

. , , , • _". ." ..... r •• I , I' i~';.' r 1 1 TS I: • • ••...t •• ~ ..... J~ ............ ~ ..... ;;"." .~. 1.' ".' . '1..-.-....... ,., .. '., . -& .'_ ,~. • . : ~',: ~."-'-. '"..:. ' ..... " ".\ :"~"~" . ........ •. '_"••. ,. '.. a; . .... ·· ..", 0 ......1" . ,vns net wt 251bs .{;" J r'"~--~ ~..." ~ . -6 • I 1'.' • .TION • I .'back Pi ~. ; .., • . .-.: '.. ~ t~·'. ' t,·~ f''':~~1d~ .. ' - ,. ! .' ~40.... t 1.>-t" , ' ... , .• . -.',I \:;2'\ . -:"' " .r I . -. l ;' .1-' " . '" ( l' j \ .i ' '.'c.,.. ~ ... ....,.J..,.. ~,. t..~~ \"i~,.1. ~~:.-....,.. .... re:!ilII::t.'? I . ! 12-6-6 \ , . t • I ; I 12-6-6 GUARANTEED ANALYSIS lOTAL NITROGEN IN) . 1 0"0 A~mor"lcai N,"ogt'n (der'.~d from ammon,alf.:·j p"c.sph;l'•• ,; an(: :In'''~'''''urll5.u:IJlel _. 4 0". Wa'~r Inso:uble NltrOQ"'" IO':"v€'d 'rum CO"'(1(:rl<;.~d Urto.:l F:)r"'3t<!ehY'lcl 7 ()O. W.lIer Su:ubte N,trrJq('n ,d.,: ,,;"'0 Irom \J'e.-i and ur€'a IOm1ddt>h.,.d", AVAILABLE Pi iOSPHORIC ACID (PIO., (derrved from ammon'dlcd phosphates) ............. ".. ..... 600 0 I . SOLUBLE POTASH (K,O) Ider:ved from mUriate of potash) . .. ...... 6.0" .. I ~ IRON EXPRESSED AS ELEMENTAL Fe (der,ved from ferrous sulfate) . 100 0 MA'nut'~rtf"~1'I by Swtffey,-e-mieal Com,-a"y. Chicago. nTfne)is 60G04 .4 "'--. .~ MONEY BACK PROMISE .,.-- . You must be pleased with the results or you Ctre entitled to your money ( ",- -". \ back. Simply send your sales S:IP to VIGORQ, Chicago. illinOis 60604 for I • , prompt refund. I , ., -"··-··-·~·l .. .--:- ~ ,". -.'. -.. -..... .. -- ... .-. \ "- .J EASY TO USE -.... - .~ ) r Apply at IC":Clst twice CI year --uut not thWl 3 times n year <1t 3 I \ , f rn~Jre f j I" months interval. -

Cricket Wales U19's 100 Ball Cup 2021 Competition Administration

Cricket Wales U19’s 100 Ball Cup 2021 Competition Administration 1. Title The title of the competition shall be the Cricket Wales U19’s 100 Ball Cup. 2. Management These rules apply to the Cricket Wales U19’s 100 Ball Cup Competition only and all decisions by County Cricket Board (CCB) or League organisers are final. 3. Entry Entry into the Cricket Wales U19’s 100 Ball Cup shall be open to all affiliated clubs / teams that are invited into leagues by the participating CCB in 2021. 4. Pitch Clubs may use fine turf or non-turf pitches for their home matches. 5. Competition Structure Each County Cricket Board, with local partners, will hold their own league competitions. The County winner shall be determined by a County Final. 6. Eligibility and Age Group Definition Any club that fields an ineligible player shall be penalised and the result of the match overturned in the favour of the opposition. 6.1 Age – A cricketer shall only be eligible to play in the competition if they are 18 or under at midnight on the 31st August in the year preceding the current season. Although there is no minimum age, it is recommended that where possible, players 15 and over should be selected. 6.2 Club Members – A cricketer shall only be eligible to play for one club in the Cricket Wales U19’s 100 Ball Cup and they must be a member of that club. 6.3 Clubs with limited numbers of U19 players can merge with, or invite players from, no more than 2 other clubs from England and Wales. -

Junior Cricket Equipment Guide Softball & Hardball

JUNIOR CRICKET EQUIPMENT GUIDE Here is a guide to the cricket equipment that is suitable for colt's cricketers. Please read it carefully before you buy cricket equipment for your child. SOFTBALL & HARDBALL ESSENTIALS 1. BATS The most important thing with a bat is to get one that is the right size and weight. Do not buy a bat in the mistaken belief that your child will ªgrow into itº ± this does not work for cricket bats. Using a bat that is too big can have a seriously negative impact on the development of your child's cricket. It makes coaching technique and hitting the ball very difficult. As a general rule bats should be lightweight. The player must be able to pick it up comfortably and play a few shadow shots with the top hand only. Size 3 & 4 bats must weigh UNDER 2lbs, in the 1lb 12oz- 1lb 14oz range. Size 5 & 6 bats should weigh in the range between 1lb 14 oz to 2lb 1oz. Size harrow (H) bats should weigh between 2lb 1oz ± 2lb 6oz. For the taller/bigger boys in U15-U17 using a full size bat, look for one that is no heavier than 2lb 8oz. Ask to weigh the bat on scales in the shop. Bats vary in quality. The different grade of willow will be reflected in the price. If you buy a bat for under £50 the chances are that it will not be made of English willow, but made of Kashmir Willow. Kashmir Willow is fine for softball, but for hardball cricket you should buy an English Willow bat. -

Evolution of Test Cricket in Last Six Decades a Univariate Time Series Analysis

Evolution of Test Cricket in Last Six Decades A Univariate Time Series Analysis Mayank Nagpal Sumit Mishra 1 Introduction We intend to analyse the structural changes in the average annual run-rate, i.e., how many runs are scored in each over, a measure of how much bat dominates the ball or how aggressively teams bat. Test cricket is the traditional format of the game. It is considered to be a snail-form of the game when we compare it with newer versions of the game, viz, ODI and T20 .A test cricket match lasting 5 days is apparently a lot less exciting for some than an ODI which lasts for eight hours or a T20 match which is matter of two-three hours. The general view is that with the advent of new technology, pitches that are more batsmen-friendly and craving for result in each game, the average run rate seems to have increased. Some analysts attribute this change to the emergence of newer formats and other innovations in the game. The question we are trying to answer is about whether these factors like those mentioned below had any significant impact on the game. The events whose effect we like to capture are: • Advent of One Day International(ODI):With dying popularity of test cricket matches during 1960s,a tournament called Gillette Cup was played in 1963 in England. The cup had sixty- five overs a side matches. This tourney was a knockout one and it became quite popular and laid foundation for a sleeker format of the game known as ODI-fifty overs a side game. -

Queensland Cricket Infrastructure Strategy 2018-2028 2019-20 Project Update Acknowledgements

QUEENSLAND CRICKET INFRASTRUCTURE STRATEGY 2018-2028 2019-20 PROJECT UPDATE ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Queensland Cricket (QC) acknowledges the significant contribution made by a number of stakeholders in the development of this Strategy. Thank you to the cricket community, including associations, local clubs, individuals and organisations that have contributed significant information and feedback. QC acknowledges the support provided by the Queensland Government in co-funding the project and its representation on the Project Control Group. Thank you also to all councils that participated in a range of consultation activities, in particular those council representatives who were members of Project Groups. Queensland Cricket Infrastructure Strategy 2018-2028 I UPDATE November 2019 CONTENTS Queensland Cricket Infrastructure Strategy ABOUT THIS DOCUMENT 1: Welcome 1 The Queensland Cricket Infrastructure Strategy (QCIS) provides the Queensland cricket community and its stakeholders with a detailed assessment and analysis of the state’s cricket 2: Executive Summary 2 facility landscape. It identifies key future venue planning and development priorities for the 2018 3: Introduction and Background 5 to 2028 period. In addition to the overarching state-wide and Premier Cricket infrastructure priorities identified, a detailed assessment, strategic directions and recommendations have been 4: Impact on cricket delivery in Queensland 8 provided for each of Queensland Cricket’s (QC’s) 12 Regions. The Strategy also highlights the 5: The ‘Value of Cricket’ 11 associated economic impact some cricket competitions and events can have on a local economy, as well as detailing the relationship between the player pathway and associated 6: Cricket in Queensland – ‘State of Play’ 14 infrastructure requirements at each level. -

Throwing Or Bowling? Biomechanical Analysis of Suspect Actions

Throwing or bowling? Biomechanical Analysis of Suspect Actions Text: Helen Bayne (née Crewe), Head Biomechanist, hpc A distinctive feature of cricket is that the bowler is required to deliver the ball with an overarm action but without throwing. The Laws of Cricket state that “a ball is fairly delivered in respect of the arm if, once the bowler’s arm has reached the level of the shoulder in the delivery swing, the elbow joint is not straightened partially or completely from that point until the ball has left the hand”. The implementation of this law has been a controversial and emotive issue ever since the earliest documented reports of umpires calling “no-ball” for throwing in the 1890s and has undoubtedly affected many bowlers’ cricket careers. In recent times, modern technology has enabled a more objective procedure for evaluating bowling action legality. Even in players who bowl with the straightest of arms, the elbow joint is not completely rigid during bowling. So, in 2005, following a review of around Carrying angle 130 spin, medium and fast bowlers who had been examined using field-based and laboratory-based testing methods, the ICC introduced a tolerance the bowler’s arm and body move through a threshold of 15 degrees. This refers specifically to complex three-dimensional range so that you could straightening of the elbow (extension) between the never be in a perfect position that would allow you points where the upper arm reaches horizontal to view the flexion-extension of the elbow. Lastly, during the delivery stride and when the ball is anatomical variations can create an illusion that the released. -

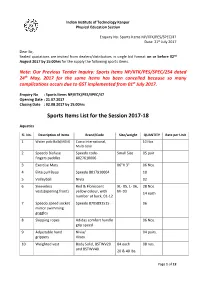

Sports Items List for the Session 2017-18

Indian Institute of Technology Kanpur Physical Education Section Enquiry No: Sports Items NP/IITK/PES/SPEC/47 Date: 21st July 2017 Dear Sir, Sealed quotations are invited from dealers/distributors in single bid format on or before 02nd August 2017 by 15:00hrs for the supply the following sports items. Note: Our Previous Tender Inquiry: Sports Items NP/IITK/PES/SPEC/254 dated 24th May, 2017 for the same items has been cancelled because so many complications occurs due to GST implemented from 01st July 2017. Enquiry No : Sports Items NP/IITK/PES/SPEC/47 Opening Date : 21.07.2017 Closing Date : 02.08.2017 by 15:00hrs Sports Items List for the Session 2017-18 Aquatics Sl. No. Description of items Brand/Code Size/weight QUANTITY Rate per Unit 1 Water polo Balls(MEN) Cosco International, 10 Nos. Multi color 2 Speedo Biofuse Speedo code- Small Size 05 pair fingers paddles 8027610006 3 Exercise Mats 06"X 3" 06 Nos. 4 Elite pull Buoy Speedo 8017910004 10 5 Volleyball Nivia 02 6 Sleeveless Red & Florescent XL- 05, L- 06, 28 Nos. vests(opening front) yellow colour, with M- 03 14 each number at back, 01-12 7 Speedo speed socket Speedo 8705893515 06 mirror swimming goggles 8 Skipping ropes Adidas comfort handle 06 Nos. grip speed 9 Adjustable hand Nivia/ 04 pairs. grippers Vinex 10 Weighted vest Body Solid, BSTWV20 04 each 08 nos. and BSTWV40 20 & 40 lbs. Page 1 of 12 11 Ankle weights with Nivia 01kg 02pairs adjustable cuff 1.5kg 02Pairs 12 Medicine Balls Nevia/ 2kg 02 Vinex 4kg 02 6kg 02 13 Squat stand Vinix/ 01 set Nelco 14 Horizontal bar Vinix/ -

One Day Limited Overs Cricket Matches Within the Province of Alberta Will Follow I.C.C

Cricket Alberta (CA) Playing Rules One day limited overs cricket matches within the Province of Alberta will follow I.C.C. rules, however, the following rules takes precedent: 1. Start of Match a. Matches shall start at the time set by the Executive of the respective League. b. If a team does not have 7 players present at the ground 15 minute prior to the scheduled match start, the other team shall be awarded the toss. c. If a team does not have 7 players present at the ground at the scheduled start time, it shall forfeit the match. The non-defaulting team shall be awarded a win. d. If a team delays the commencement of a match for any reason other than in 1(c), it shall be penalized by deducting 1 over from their batting quota for each 4 minutes of delay. 2. Length of Match a. All matches in the highest division of a league shall be 50 overs per team. For all other divisions, leagues have the right to adjust the number of overs. b. Both innings shall be completed on the same day. c. The break between innings shall be set by the leagues. d. A mandatory 5 minute water break is allowed per innings, but the break shall occur after one hour of playing time has elapsed. Other breaks may be given at the umpires’ discretion. e. No bowler shall bowl more than 1/5 of the number of overs allotted to each innings at the start of the first innings. 3. Time Limit a. -

Biomechanics in Testing the Legality of a Bowling Action in Cricket

BIOMECHANICS IN TESTING THE LEGALITY OF A BOWLING ACTION IN CRICKET David Lloyd, Jacque Alderson and Bruce Elliott Department of Human Movement and Exercise Science The University of Western Australia, Perth, Australia Movement analysis in sport and leisure is clearly the domain of the sports biomechanist. Technique modifications to improve performance or reduce the incidence of injury are currently administered. However, the analysis of sporting movements, from a legal perspective, is a more recent development. This paper discusses the procedures used in testing the legality of actions used in bowling in cricket. KEY WORDS: motion analysis, cricket, Vicon INTRODUCTION: The current no ball law in cricket with reference to throwing states: “the arm should not be straightened in the part of the delivery that immediately precedes ball release” The sport biomechanist in assessing the legality of a bowling action must first decide on the design of the analysis protocol. Questions that need to be answered before deciding on this protocol are: Is movement analysed in a laboratory setting representative of what occurs in the game environment? Also, are athletes capable of changing their action to comply with regulations when being filmed in a laboratory environment? Does the lack of accuracy in determining joint centres under baggy clothing worn in match conditions, lead to uncertainty about the error in the collected data? The laws of the game must also be read from both a “spirit of the game” and a biomechanical perspective. In fast bowling the phrase “immediately before delivery” must be interpreted from both those perspectives. This paper will show how the Sri Lankin spin bowler Muttiah Muralitharan on being “called for throwing” was analysed within the biomechanics laboratory of the Department of Human Movement and Exercise Science. -

Kanga Cricket

KANGA CRICKET RULES AND INFORMATION COACHES ARE ENCOURAGED TO DISCUSS THE RULES and TIME CONSTRAINTS WITH THEIR OPPONENTS BEFORE EACH MATCH TO CLARIFYTHESE RULES Introduction The aim of Kanga Cricket is to enable EVERY player to have a chance of success, as well as participating in an enjoyable game. To achieve this, game Coordinators should adopt a flexible attitude and be prepared to adjust wicket length, speed of bowling, etc. to suit each player’s size, strength and ability. Coordinators should be prepared to offer ON THE SPOT coaching/assistance when the need arises – this also includes encouragement and reinforcement. Teams • Each side may have 6 to a maximum of 8 players (no more, or games take too long). Equipment And Grounds • Only approved KANGA equipment may be used. • The pitch should be 14 - 16 metres long. • The distance from pitch to boundary should not exceed 30 metres (boundaries optional). Batting • Batters bat in pairs and continue to bat (irrespective of score or dismissals) for 4 overs per pair (2 overs suggested for initial games of season). • If a team has an odd number of players, or less players than the other team, then one or more players may bat twice. • Batters change ends - - after each dismissal - at the end of each over - when no run has been scored from 3 successive balls • 4's and 6's should be allowed only if the boundary is clearly defined (umpires should confer on this before the match starts). • Batters may be dismissed only if bowled, caught, run out, stumped or hit wicket.