Clawbacks: Prospective Contract Measures in an Era of Excessive Executive Compensation and Ponzi Schemes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Exhibit a Pg 1 of 40

09-01161-smb Doc 246-1 Filed 03/04/16 Entered 03/04/16 10:33:08 Exhibit A Pg 1 of 40 EXHIBIT A 09-01161-smb Doc 246-1 Filed 03/04/16 Entered 03/04/16 10:33:08 Exhibit A Pg 2 of 40 Baker & Hostetler LLP 45 Rockefeller Plaza New York, NY 10111 Telephone: (212) 589-4200 Facsimile: (212) 589-4201 Attorneys for Irving H. Picard, Trustee for the substantively consolidated SIPA Liquidation of Bernard L. Madoff Investment Securities LLC and the Estate of Bernard L. Madoff UNITED STATES BANKRUPTCY COURT SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK SECURITIES INVESTOR PROTECTION CORPORATION, No. 08-01789 (SMB) Plaintiff-Applicant, SIPA LIQUIDATION v. (Substantively Consolidated) BERNARD L. MADOFF INVESTMENT SECURITIES LLC, Defendant. In re: BERNARD L. MADOFF, Debtor. IRVING H. PICARD, Trustee for the Liquidation of Bernard L. Madoff Investment Securities LLC, Plaintiff, Adv. Pro. No. 09-1161 (SMB) v. FEDERICO CERETTI, et al., Defendants. 09-01161-smb Doc 246-1 Filed 03/04/16 Entered 03/04/16 10:33:08 Exhibit A Pg 3 of 40 TRUSTEE’S FIRST SET OF REQUESTS FOR PRODUCTION OF DOCUMENTS AND THINGS TO DEFENDANT KINGATE GLOBAL FUND, LTD. PLEASE TAKE NOTICE that in accordance with Rules 26 and 34 of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure (the “Federal Rules”), made applicable to this adversary proceeding under the Federal Rules of Bankruptcy Procedure (the “Bankruptcy Rules”) and the applicable local rules of the United States District Court for the Southern District of New York and this Court (the “Local Rules”), Irving H. -

Bernie Madoff After Ten Years; Recent Ponzi Scheme Cases, and the Uniform Fraudulent Transactions Act by Herrick K

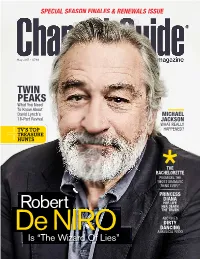

Bernie Madoff After Ten Years; Recent Ponzi Scheme Cases, and the Uniform Fraudulent Transactions Act By Herrick K. Lidstone, Jr. Burns, Figa & Will, P.C. Greenwood Village, CO 80111 Remember Bernie? Ten Years Later. On December 11, 2018, the Motley Fool (https://www.fool.com/investing/2018/12/11/3-lessons-from-bernie-madoffs-ponzi-scheme- arrest.aspx) published an article commemorating the tenth anniversary of Bernie Madoff’s arrest in 2008. Prior to his arrest, Madoff was a well-respected leader of the investment community, a significant charitable benefactor, and a Wall Street giant. That changed when Madoff was arrested and his financial empire was revealed to be the biggest Ponzi scheme in history. In March 2009, Madoff pleaded guilty to 11 different felony charges, including money laundering, perjury, fraud, and filing false documents with the Securities and Exchange Commission. Madoff was sentenced to 150 years in federal prison where he remains today at the age of 80. Five of his employees were also convicted and are serving prison sentences, one of his sons committed suicide in December 2010, and his wife Ruth’s lifestyle changed dramatically. (In his plea deal with prosecutors, Ruth was allowed to keep $2.5 million for herself.) [https://nypost.com/2017/05/14/the-sad-new-life-of-exiled-ruth-madoff/]. All of this was chronicled in The Wizard of Lies, a 2017 made-for-television movie starring Robert DeNiro as Bernie Madoff and Michelle Pfeiffer as Ruth Madoff. [https://www.imdb.com/title/tt1933667/]. The Madoff Ponzi Scheme. Bernie Madoff and his sons, as we recall, managed a multibillion dollar Ponzi scheme over a large number of years from Bernie’s Manhattan offices with investors all over the world and here in Colorado. -

Read Chapter 1 As a PDF

1 An Earthquake on Wall Street Monday, December 8, 2008 He is ready to stop now, ready to just let his vast fraud tumble down around him. Despite his confident posturing and his apparent imperviousness to the increasing market turmoil, his investors are deserting him. The Spanish banking executives who visited him on Thanksgiving Day still want to withdraw their money. So do the Italians running the Kingate funds in London, and the managers of the fund in Gibraltar and the Dutch-run fund in the Caymans, and even Sonja Kohn in Vienna, one of his biggest boosters. That’s more than $1.5 billion right there, from just a handful of feeder funds. Then there’s the continued hemorrhaging at Fairfield Greenwich Group—$980 million through November and now another $580 million for December. If he writes a check for the December redemptions, it will bounce. There’s no way he can borrow enough money to cover those with- drawals. Banks aren’t lending to anyone now, certainly not to a midlevel wholesale outfit like his. His brokerage firm may still seem impressive to his trusting investors, but to nervous bankers and harried regulators today, Bernard L. Madoff Investment Securities is definitely not “too big to fail.” Last week he called a defense lawyer, Ike Sorkin. There’s probably not much that even a formidable attorney like Sorkin can do for him at this point, but he’s going to need a lawyer. He made an appointment for 2 | The Wizard of Lies 11:30 am on Friday, December 12. -

TWIN PEAKS What You Need to Know About David Lynch’S MICHAEL

Time-Sensitive SPECIAL SEASON FINALES & RENEWALS ISSUE PERIODICALS Channel Guide Class Publication Postmaster please deliver by the 1st of the month NAT magazine May 2017 • $7.99 TWIN PEAKS What You Need To Know About David Lynch’s MICHAEL channelguidemag.com 18-Part Revival JACKSON WHAT REALLY TV’S TOP HAPPENED? TREASURE HUNTS PREMIERING 5/9 ON DEMAND THE BACHELORETTE PROMISES THE “MOST DRAMATIC THING EVER!” PRINCESS DIANA HER LIFE HER DEATH Robert THE TRUTH ABC GIVES May 2017 May DIRTY DANCING De NIRO A MUSICAL REDO Is “The Wizard Of Lies” WATCH THE 10 MINUTE FREE PREVIEW SHORT LIST For More ReMIND magazine SEASON offers fresh takes on FINALE popular entertainment DATES We Break Down The Month’s See Page 8 from days gone by. Biggest And Best Programming So Each issue has dozens May You Never Miss A Must-See Minute. of brain-teasing 1 16 23 puzzles, trivia quizzes, Lucifer, FOX — New Episodes NCIS, CBS — Season Finale classic comics and Taken, NBC — Season Finale NCIS: New Orleans, CBS — Season Finale features from the 2 NBA: Western Conference Finals, The Mick, FOX — Season Finale Game 1, ESPN 1950s-1980s! Victorian Slum House, PBS Tracy Morgan: Staying Alive, N e t fl i x — New Series American Epic, PBS — New Series 17 < 5 Downward Dog, ABC — New Series Blue Bloods, CBS — Season Finale Downward Dog, ABC — Sneak Peek Bull, CBS — Season Finale The Mars Generation, N e t fl i x Criminal Minds: Beyond Borders, CBS The Flash, The CW — Season Finale Sense8, N e t fl i x — New Episodes — Season Finale NBA: Eastern Conference Finals, Brooklyn -

Journal of American Studies the Madoff Paradox: American Jewish

Journal of American Studies http://journals.cambridge.org/AMS Additional services for Journal of American Studies: Email alerts: Click here Subscriptions: Click here Commercial reprints: Click here Terms of use : Click here The Madoff Paradox: American Jewish Sage, Savior, and Thief MICHAEL BERKOWITZ Journal of American Studies / Volume 46 / Issue 01 / February 2012, pp 189 202 DOI: 10.1017/S0021875811001423, Published online: 09 March 2012 Link to this article: http://journals.cambridge.org/abstract_S0021875811001423 How to cite this article: MICHAEL BERKOWITZ (2012). The Madoff Paradox: American Jewish Sage, Savior, and Thief. Journal of American Studies, 46, pp 189202 doi:10.1017/ S0021875811001423 Request Permissions : Click here Downloaded from http://journals.cambridge.org/AMS, IP address: 144.82.107.48 on 17 Oct 2012 Journal of American Studies, (), , – © Cambridge University Press doi:./S The Madoff Paradox: American Jewish Sage, Savior, and Thief MICHAEL BERKOWITZ Bernie Madoff perpetrated a Ponzi scheme on a scale that was gargantuan even compared with the outrageously destructive Enron and Worldcom debacles. A major aspect of the Madoff story is his rise as a specifically American Jewish type, who self-consciously exploited stereotypes to inspire trust and confidence in his counsel. Styling himself as a benefactor and protector of Jews as individuals and institutional Jewish interests, and possibly in the guise of the Jewish historical trope of shtadlan (intercessor), he was willing to threaten the well-being of all those enmeshed in his empire. The license granted to Madoff stemmed in part from the extent to which he appeared to diverge from earlier Jewish financial titans, such as Ivan Boesky and Michael Milken, in that he epitomized an absolute “insider”–as opposed to an “outsider” or marginal figure. -

ABC Orders 1970S Model Wars Drama Pilot Inspired by Eileen Ford Biography

Reviews Box Office Heat Vision Coming Soon 4M:2O5 VPIMES PDT 10/20/2016 by Rebecca Ford TV FACE BTOWOITK TEEMRAI LC MOME MENTS BUSINESS STYLE POLITICS TECH CULTURE AWARDS VIDEO SITES SUBSCRIBE SITE TOOLS Tara Ziemba/WireImage Justin Chatwin Justin Chatwin (Shameless), Peter Stormare (Fargo), and Mark Thompson (KLOS’ The Mark and Brian Show) have signed on to star in crime drama Legacy, directed by David A. Armstrong. With a script by Edward Cornett and Valerie Grant, Legacy follows a rookie Cleveland detective who is desperate to escape from under the shadow of his late father, a disgraced cop killed in the line of duty. He works to solve his first important case while unwittingly under the watchful eye of a ghost- like assassin. William K. Baker is producing in association with Think Media. Principal photography will begin later in October. Armstrong, previously the cinematographer on the Saw film franchise, is repped by Original Artists and Felker Toczek. Grant also is repped by Original Artists and Felker Toczek. Chatwin, who’s appeared on Shameless, Orphan Black and American Gothic on TV, will soon be seen in the film CHiPs with Dax Shepard. He is repped by UTA. Stormare is repped by ICM, and Thompson is managed by The Beddingfield Company. READ MORE MET GALA WILL BE THE BACKDROP FOR NOT ONE, BUT TWO UPCOMING HEIST FILMS 12:28 PM PDT 8/18/2016 by Sam Reed FACE TBWOOITK TEEMRAI LC MOMEMENTS AP Images/Invision Rihanna at the 2015 Met Gala Fashion's biggest night is headed to the big screen. -

Baker & Hostetler LLP 45 Rockefeller Plaza New York

Baker & Hostetler LLP Hearing Date: October 19, 2011 45 Rockefeller Plaza Hearing Time: 10:00 A.M. EST New York, New York 10111 Telephone: (212) 589-4200 Objection Deadline: October 5, 2011 Facsimile: (212) 589-4201 Time: 4:00 P.M. EST Irving H. Picard Email: [email protected] David J. Sheehan Email: [email protected] Seanna R. Brown Email: [email protected] Jacqlyn R. Rovine Email: [email protected] Attorneys for Irving H. Picard, Trustee for the Substantively Consolidated SIPA Liquidation of Bernard L. Madoff Investment Securities LLC And Bernard L. Madoff UNITED STATES BANKRUPTCY COURT SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK SECURITIES INVESTOR PROTECTION CORPORATION, Adv. Pro. No. 08-01789 (BRL) Plaintiff, SIPA Liquidation v. (Substantively Consolidated) BERNARD L. MADOFF INVESTMENT SECURITIES LLC, Defendant. In re: BERNARD L. MADOFF, Debtor. SEVENTH APPLICATION OF TRUSTEE AND BAKER & HOSTETLER LLP FOR ALLOWANCE OF INTERIM COMPENSATION FOR SERVICES RENDERED AND REIMBURSEMENT OF ACTUAL AND NECESSARY EXPENSES INCURRED FROM FEBRUARY 1, 2011 THROUGH MAY 31, 2011 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page I. PRELIMINARY STATEMENT ....................................................................................... 1 II. BACKGROUND ............................................................................................................... 6 A. THE SIPA LIQUIDATION ................................................................................... 6 B. THE TRUSTEE, COUNSEL, AND CONSULTANTS ........................................ 8 C. PRIOR COMPENSATION -

Stipulation and Order As to Ruth Madoff

Case 1:09-cr-00213-DC Document 94 Filed 06/26/2009 Page 1 of 32 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK ------------------------------- X UNITED STATES OF AMERICA STIPULATION AND ORDER - v.- 09 Cr. 213 (DC) BERNARD L. MADOFF, Defendant. ------------------------------- X RUTH MADOFF, Interested Party. ------------------------------- X WHEREAS, on or about June_, 2009, the Court entered a Preliminary Order of Forfeiture (Final as to the Defendant) (the "Preliminary Order") as to BERNARD L. MADOFF, the defendant ("MADOFF" or the "defendant"), which is attached hereto and incorporated herein by reference as if set out in full; WHEREAS, in the Preliminary Order, which was entered on the defendant's consent, the Government and the defendant stipulated that, if the Government were to apply for an order of criminal forfeiture to be imposed as part of the defendant's sentence, and the Court were to hold a hearing on the Government's claims for forfeiture: (i) the Government could prove by a preponderance of the evidence that the defendant is liable for a personal money judgment in the amount of $170,000,000,000, a sum of money representing the amount of property constituting or derived from proceeds traceable to Case 1:09-cr-00213-DC Document 94 Filed 06/26/2009 Page 2 of 32 the commission of the SUA Offenses charged in Counts One, Three, Four, and Eleven of the Information, and property traceable to such property, as alleged in the First Forfeiture Allegation; and (ii) the Government could prove by a preponderance of the evidence -

Sipc Trustee Sues Ruth Madoff

Media Contact: Kevin McCue [email protected] 216-861-7576 SIPC TRUSTEE IRVING PICARD SUES FOUR MADOFF FAMILY MEMBERS Seeks Recapture Of At Least $198,743,299 From Madoff’s Brother, Sons, and Niece NEW YORK, NY, October 2, 2009 - Irving H. Picard, the Trustee appointed to liquidate the business of Bernard L. Madoff Investment Securities LLC ("BLMIS"), filed suit today against four Madoff family members who held senior positions at BLMIS. Named in the suit are Madoff’s brother, Peter Madoff, who was BLMIS’s Chief Compliance Officer, Madoff’s two sons, Andrew and Mark, who served as Co-Directors of Trading at BLMIS, and Madoff’s niece, Shana Madoff, who was BLMIS’s Compliance Director. Through the lawsuit filed in Bankruptcy Court in Manhattan by Mr. Picard’s law firm, Baker & Hostetler LLP, the Trustee seeks to recapture for the benefit of Madoff’s investors at least $198,743,299 in customer funds which the Trustee alleges were diverted from BLMIS’s investment advisory business and transferred directly to the family members or spent on their behalf. In the Complaint, Mr. Picard explains that the family members’ “management responsibilities extended through trading operations, customer relationships, and legal and regulatory compliance, yet they were completely derelict in these duties and responsibilities. As a result, they either failed to detect or failed to stop the fraud, thereby enabling and facilitating the Ponzi scheme at BLMIS. Simply put, if the Family Members had been doing their jobs—honestly and faithfully—the Madoff Ponzi scheme might never have succeeded, or continued for so long.” Mr. -

Declaration of Bruce G. Dubinsky, Mst, Cpa, Cfe, Cva, Cff, Maff

09-01182-smb Doc 296 Filed 11/25/15 Entered 11/25/15 13:22:24 Main Document Pg 1 of 4 UNITED STATES BANKRUPTCY COURT SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK SECURITIES INVESTOR PROTECTION CORPORATION, Adv. Pro. No. 08-01789 (SMB) Plaintiff-Applicant, SIPA LIQUIDATION v. (Substantively Consolidated) BERNARD L. MADOFF INVESTMENT SECURITIES LLC, Defendant. In re: BERNARD L. MADOFF, Debtor. IRVING H. PICARD, Trustee for the Liquidation of Bernard L. Madoff Investment Securities LLC, Plaintiff, v. Adv. Pro. No. 09-01182 (SMB) J. EZRA MERKIN, GABRIEL CAPITAL, L.P., ARIEL FUND LTD., ASCOT PARTNERS, L.P., ASCOT FUND LTD., GABRIEL CAPITAL CORPORATION, Defendants. DECLARATION OF BRUCE G. DUBINSKY, MST, CPA, CFE, CVA, CFF, MAFF 09-01182-smb Doc 296 Filed 11/25/15 Entered 11/25/15 13:22:24 Main Document Pg 2 of 4 I, Bruce G. Dubinsky, declare, under penalty of perjury, that the foregoing is true and correct: 1. I am a Managing Director in the Disputes & Investigations practice at Duff & Phelps, LLC (“D&P”). My practice at D&P places special emphasis on providing forensic accounting, fraud investigation and dispute analysis services to law firms litigating commercial cases, as well as corporations, governmental agencies and law enforcement bodies in a variety of situations. 2. I was retained by the law firm of Baker & Hostetler LLP (“Baker”), counsel for Irving H. Picard, Trustee (“Trustee”) for the substantively consolidated liquidation of Bernard L. Madoff Investment Securities LLC (“BLMIS”) under the Securities Investor Protection Act (“SIPA”), 15 U.S.C. §§78aaa et seq., and the estate of Bernard L. -

COMPLAINT Individually and on Behalf of the Estate of Leon Greenberg; and DONNA MCBRIDE, Individually and Derivatively on Behalf of Beacon Associates LLC II

Baker & Hostetler LLP 45 Rockefeller Plaza New York, NY 10111 Telephone: (212) 589-4200 Facsimile: (212) 589-4201 David J. Sheehan Email: [email protected] Attorneys for Irving H. Picard, Esq., Trustee for the Substantively Consolidated SIPA Liquidation of Bernard L. Madoff Investment Securities LLC and Bernard L. Madoff UNITED STATES BANKRUPTCY COURT SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK SECURITIES INVESTOR PROTECTION CORPORATION, Adv. Pro. No. 08-01789 (BRL) Plaintiff, SIPA LIQUIDATION v. (Substantively Consolidated) BERNARD L. MADOFF INVESTMENT SECURITIES LLC, Defendant. In re: BERNARD L. MADOFF, Debtor. IRVING H. PICARD, Trustee for the Liquidation of Bernard L. Madoff Investment Securities LLC, Adv. Pro. No. ________ Plaintiff, v. RICHARD I. STAHL; REED ABEND; THE LAUTENBERG FOUNDATION, JOSHUA S. LAUTENBERG, ELLEN LAUTENBERG; MATIAS ERAUSQUIN, ENRIQUE ERAUSQUIN, LILIANA CONTRONE and YOLANDA FRISCHKNECHT, on behalf of themselves and those they purport to represent; NEVILLE SEYMOUR DAVIS, on behalf of himself and those he purports to represent; EMILIO CHAVEZ, JR.; RETIREMENT PROGRAM FOR EMPLOYEES OF THE TOWN OF FAIRFIELD, THE RETIREMENT PROGRAM FOR POLICE OFFICERS AND FIREMEN OF THE TOWN OF FAIRFIELD and THE TOWN OF FAIRFIELD; FLB FOUNDATION, LTD., JAY WEXLER, individually and derivatively on behalf of Rye Select Broad Market Prime Fund, L.P.; DANIEL RYAN and THERESA RYAN, individually and on behalf of the RYAN TRUST; MATTHEW GREENBERG, WALTER GREENBERG and DORIS GREENBERG, COMPLAINT individually and on behalf of the estate of Leon Greenberg; and DONNA MCBRIDE, individually and derivatively on behalf of Beacon Associates LLC II, Defendants. Irving H. Picard, Esq., as trustee (the “Trustee”) for the substantively consolidated liquidation of the business of Bernard L. -

Baker & Hostetler

Baker & Hostetler LLP 45 Rockefeller Plaza New York, New York 10111 Telephone: (212) 589-4200 Facsimile: (212) 589-4201 David J. Sheehan Fernando A. Bohorquez, Jr. Keith R. Murphy Attorneys for Irving H. Picard, Trustee for the Substantively Consolidated SIPA Liquidation of Bernard L. Madoff Investment Securities LLC and Bernard L. Madoff UNITED STATES BANKRUPTCY COURT SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK SECURITIES INVESTOR PROTECTION CORPORATION, Adv. Pro. No. 08-01789 (BRL) Plaintiff-Applicant, SIPA LIQUIDATION v. (Substantively Consolidated) BERNARD L. MADOFF INVESTMENT SECURITIES LLC, AMENDED Defendant. COMPLAINT In re: BERNARD L. MADOFF, Debtor. IRVING H. PICARD, Trustee for the Liquidation of Bernard L. Madoff Investment Securities LLC, Plaintiff, Adv. Pro. No. 10-5287 (BRL) v. SAUL B. KATZ, in his individual capacity, and as trustee of the Katz 2002 Descendants’ Trust; FRED WILPON, in his individual capacity, as trustee of the Wilpon 2002 Descendants’ Trust, and as co-executor of the Estate Of Leonard Schreier; RICHARD WILPON, in his individual capacity, as trustee of the Fred Wilpon Family Trust, and as trustee of the Saul B. Katz Family Trust; MICHAEL KATZ, in his individual capacity, and as the trustee of the Saul B. Katz Family Trust; JEFFREY WILPON, in his individual capacity, and as beneficiary of the Fred Wilpon Family Trust; DAVID KATZ, in his individual capacity, as trustee of the Saul B. Katz Family Trust, and as beneficiary of the Saul B. Katz Family Trust; GREGORY KATZ, in his individual capacity, and as beneficiary of the Katz 2002 Descendants’ Trust; ARTHUR FRIEDMAN; L. THOMAS OSTERMAN; MARVIN B. TEPPER; ESTATE OF LEONARD SCHREIER, JASON BACHER as co-executor of the Estate of Leonard Schreier; METS LIMITED PARTNERSHIP; STERLING METS LP; STERLING METS ASSOCIATES; STERLING METS ASSOCIATES II; METS ONE LLC; METS II LLC; METS PARTNERS, INC.; C.D.S.