Bernie Madoff After Ten Years; Recent Ponzi Scheme Cases, and the Uniform Fraudulent Transactions Act by Herrick K

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Exhibit a Pg 1 of 40

09-01161-smb Doc 246-1 Filed 03/04/16 Entered 03/04/16 10:33:08 Exhibit A Pg 1 of 40 EXHIBIT A 09-01161-smb Doc 246-1 Filed 03/04/16 Entered 03/04/16 10:33:08 Exhibit A Pg 2 of 40 Baker & Hostetler LLP 45 Rockefeller Plaza New York, NY 10111 Telephone: (212) 589-4200 Facsimile: (212) 589-4201 Attorneys for Irving H. Picard, Trustee for the substantively consolidated SIPA Liquidation of Bernard L. Madoff Investment Securities LLC and the Estate of Bernard L. Madoff UNITED STATES BANKRUPTCY COURT SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK SECURITIES INVESTOR PROTECTION CORPORATION, No. 08-01789 (SMB) Plaintiff-Applicant, SIPA LIQUIDATION v. (Substantively Consolidated) BERNARD L. MADOFF INVESTMENT SECURITIES LLC, Defendant. In re: BERNARD L. MADOFF, Debtor. IRVING H. PICARD, Trustee for the Liquidation of Bernard L. Madoff Investment Securities LLC, Plaintiff, Adv. Pro. No. 09-1161 (SMB) v. FEDERICO CERETTI, et al., Defendants. 09-01161-smb Doc 246-1 Filed 03/04/16 Entered 03/04/16 10:33:08 Exhibit A Pg 3 of 40 TRUSTEE’S FIRST SET OF REQUESTS FOR PRODUCTION OF DOCUMENTS AND THINGS TO DEFENDANT KINGATE GLOBAL FUND, LTD. PLEASE TAKE NOTICE that in accordance with Rules 26 and 34 of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure (the “Federal Rules”), made applicable to this adversary proceeding under the Federal Rules of Bankruptcy Procedure (the “Bankruptcy Rules”) and the applicable local rules of the United States District Court for the Southern District of New York and this Court (the “Local Rules”), Irving H. -

BERNARD L. MADOFF INVESTMENT SECURITIES LLC, Debtor

Case 20-1334, Document 73, 08/06/2020, 2902485, Page1 of 180 20-1334 IN THE United States Court of Appeals FORd THE SECOND CIRCUIT IN RE: BERNARD L. MADOFF INVESTMENT SECURITIES LLC, Debtor. IRVING H. PICARD, TRUSTEE FOR THE LIQUIDATION OF BERNARD L. MADOFF INVESTMENT SECURITIES LLC, Plaintiff-Appellant, SECURITIES INVESTOR PROTECTION CORPORATION, Appellant, —against— LEGACY CAPITAL LTD., KHRONOS LLC, Defendants-Appellees. ON APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES BANKRUPTCY COURT FOR THE SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK BRIEF AND SPECIAL APPENDIX FOR PLAINTIFF-APPELLANT ROY T. ENGLERT, JR. DAVID J. SHEEHAN MATTHEW M. MADDEN SEANNA R. BROWN LESLIE C. ESBROOK AMY E. VANDERWAL ROBBINS, RUSSELL, ENGLERT, BAKER & HOSTETLER LLP ORSECK, UNTEREINER & SAUBER LLP 45 Rockefeller Plaza 2000 K Street NW, 4th Floor New York, New York 10111 Washington, D.C. 20006 (212) 589-4200 (202) 775-4500 Attorneys for Plaintiff-Appellant Special Counsel to the Trustee Irving H. Picard, Trustee for the Liquidation of Bernard L. Madoff Investment Securities LLC Case 20-1334, Document 73, 08/06/2020, 2902485, Page2 of 180 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page STATEMENT OF JURISDICTION ........................................................... 1 ISSUES PRESENTED ............................................................................... 2 STATEMENT OF CASE ............................................................................ 3 A. The Collapse Of BLMIS’ Ponzi Scheme And The Resulting SIPA Liquidation .................................................... 3 B. The District Court’s 2014 -

The Madoff Investment Securities Fraud: Regulatory and Oversight Concerns and the Need for Reform Hearing Committee on Banking

S. HRG. 111–38 THE MADOFF INVESTMENT SECURITIES FRAUD: REGULATORY AND OVERSIGHT CONCERNS AND THE NEED FOR REFORM HEARING BEFORE THE COMMITTEE ON BANKING, HOUSING, AND URBAN AFFAIRS UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED ELEVENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION ON HOW THE SECURITIES REGULATORY SYSTEM FAILED TO DETECT THE MADOFF INVESTMENT SECURITIES FRAUD, THE EXTENT TO WHICH SECURITIES INSURANCE WILL ASSIST DEFRAUDED VICTIMS, AND THE NEED FOR REFORM JANUARY 27, 2009 Printed for the use of the Committee on Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs ( Available at: http://www.access.gpo.gov/congress/senate/senate05sh.html U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 50–465 PDF WASHINGTON : 2009 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate Nov 24 2008 08:33 Jul 07, 2009 Jkt 048080 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 S:\DOCS\50465.TXT JASON COMMITTEE ON BANKING, HOUSING, AND URBAN AFFAIRS CHRISTOPHER J. DODD, Connecticut, Chairman TIM JOHNSON, South Dakota RICHARD C. SHELBY, Alabama JACK REED, Rhode Island ROBERT F. BENNETT, Utah CHARLES E. SCHUMER, New York JIM BUNNING, Kentucky EVAN BAYH, Indiana MIKE CRAPO, Idaho ROBERT MENENDEZ, New Jersey MEL MARTINEZ, Florida DANIEL K. AKAKA, Hawaii BOB CORKER, Tennessee SHERROD BROWN, Ohio JIM DEMINT, South Carolina JON TESTER, Montana DAVID VITTER, Louisiana HERB KOHL, Wisconsin MIKE JOHANNS, Nebraska MARK R. WARNER, Virginia KAY BAILEY HUTCHISON, Texas JEFF MERKLEY, Oregon MICHAEL F. BENNET, Colorado COLIN MCGINNIS, Acting Staff Director WILLIAM D. -

Case 1:14-Cv-01041-LLS Document 2 Filed 02/19/14 Page 1 of 116 Case 1:14-Cv-01041-LLS Document 2 Filed 02/19/14 Page 2 of 116

Case 1:14-cv-01041-LLS Document 2 Filed 02/19/14 Page 1 of 116 Case 1:14-cv-01041-LLS Document 2 Filed 02/19/14 Page 2 of 116 Plaintiffs Central Laborers’ Pension Fund and Steamfitters Local 449 Pension Fund (collectively, “Plaintiffs”), by their undersigned attorneys, allege based upon: (i) Plaintiffs’ counsel’s personal interviews of Bernard Madoff (“Madoff”); (ii) the Deferred Prosecution Agreement entered into between the United States Attorney’s Office for the Southern District of New York (“U.S. Attorney”) and JPMorgan Chase Bank, N.A. (along with its parent company, affiliates, and predecessors in interest, “JPMorgan” or “the Bank”); (iii) the complaint filed against JPMorgan by Irving Picard (the “Trustee”), as trustee for the liquidation of Bernard L. Madoff Investment Securities LLC (“BMIS,” “Madoff Securities,” or “BLM”), in Irving H. Picard v. JPMorgan Chase & Co., No. 11-cv-913 (CM) (S.D.N.Y) (Dkt. No. 50) (the “Trustee Complaint”); (iv) filings with the Securities and Exchange Commission (“SEC”) and other public information; (v) information and belief; and (vi) as to allegations pertaining to themselves, personal knowledge, as follows: OVERVIEW OF THE ACTION 1. On January 6, 2014, JPMorgan entered into the Deferred Prosecution Agreement wherein JPMorgan agreed to pay $2.6 billion to various federal authorities and plaintiffs in civil cases stemming from two felony violations of the Bank Secrecy Act (“BSA”) in connection with its two-decades-long financial relationship with Madoff. 2. As part of the Deferred Prosecution Agreement, JPMorgan admitted and stipulated that the facts set forth in the Statement of Facts, attached to the Deferred Prosecution Agreement, were true and accurate. -

Read Chapter 1 As a PDF

1 An Earthquake on Wall Street Monday, December 8, 2008 He is ready to stop now, ready to just let his vast fraud tumble down around him. Despite his confident posturing and his apparent imperviousness to the increasing market turmoil, his investors are deserting him. The Spanish banking executives who visited him on Thanksgiving Day still want to withdraw their money. So do the Italians running the Kingate funds in London, and the managers of the fund in Gibraltar and the Dutch-run fund in the Caymans, and even Sonja Kohn in Vienna, one of his biggest boosters. That’s more than $1.5 billion right there, from just a handful of feeder funds. Then there’s the continued hemorrhaging at Fairfield Greenwich Group—$980 million through November and now another $580 million for December. If he writes a check for the December redemptions, it will bounce. There’s no way he can borrow enough money to cover those with- drawals. Banks aren’t lending to anyone now, certainly not to a midlevel wholesale outfit like his. His brokerage firm may still seem impressive to his trusting investors, but to nervous bankers and harried regulators today, Bernard L. Madoff Investment Securities is definitely not “too big to fail.” Last week he called a defense lawyer, Ike Sorkin. There’s probably not much that even a formidable attorney like Sorkin can do for him at this point, but he’s going to need a lawyer. He made an appointment for 2 | The Wizard of Lies 11:30 am on Friday, December 12. -

Ex Nasdaq Börsenchef Madoff

Menü aus TMW Forum TMW von A bis Z Dow Jones News Emfis News Thema: Ex Nasdaq Börsenchef Madoff: 50 Milliarden Dollar Schneeballbetrug Firmen-Findex Finanzen Meine TerminmarktWelt Mitglied werden Das Thema hat 53 Beiträge: (Jetzt kostenfrei bis Ende Gehe zu Seite: 1 2 3 oder alle Beiträge zeigen Juni 2009) Registrierung TMW Forumregeln Hilfe Richard Ebert Am: 07.01.2009 14:09:52 Gelesen: 1212 # 29 @ Kontakt / Impressum Werbung Madoff droht U-Haft: Wertgegenstände verschickt Futures Kurse + Charts Fondsprofessionell.de / ir (06.01.09) - 50 Milliarden Dollar an Investoren-Geldern soll er mittels eines Kurse Aktien L&S gigantischen Schneeball-Systems verbrannt haben und es scheint kaum vorstellbar, dass Bernard Kurse chi-x Madoff und seine Reputation nach Bekanntwerden dessen, einigermaßen unbeschadet aus der Kurse Gold (Eurex) Weitere Kurse - Indices Sache hervorgehen. Ein Punkt, der Madoff wohl bewusst ist, den er offenbar aber zumindest versucht, noch ein wenig auszureizen. Getreu dem Motto ‚Ist der Ruf erst ruiniert, lebt es sich Chartbuch gänzlich ungeniert“, soll der unter Hausarrest stehende Bernard Madoff angeblich versucht haben, Chartbuch (alte Version) Juwelen, Uhren, Stifte und andere Wertgegenstände aus seinem persönlichen Besitz im Wert von MetaStock-Forum.de rund einer Million US-Dollar zur Seite zu schaffen, indem er sie an andere Parteien verschickte. Dies MetaStock Intensiv warf ihm die Staatsanwaltschaft in einer gerichtlichen Anhörung vor, wobei sich der Wert auf ein Schulung einziges Päckchen beziehe, wie es auf BBC heißt. TerminmarktBuch.de Bücherbörse Dies käme einem klaren Verstoß gegen die Kautionsauflagen gleich – laut der unter anderem auch ETM & Traders Madoffs persönliche Vermögenswerte gerichtlich ‚eingefroren’ sind – und könnte in der Konsequenz TerminmarktSeminar.de Crepart-Forum.de Untersuchungshaft für Madoff bedeuten. -

The Madoff Fraud

MVE220 Financial Risk The Madoff Fraud Shahin Zarrabi – 9111194354 Lennart Lundberg – 9106102115 Abstract: A short explanation of the Ponzi scheme carried out by Bernard Madoff, the explanation to how it could go on for such a long period of time and an investigation on how it could be prevented in the future. The report were written jointly by the group members and the analysis was made from discussion within the group 1. Introduction Since the ascent of money, different techniques have been developed and carried out to fool people of their assets. These methods have evolved together with advances in technology, and some have proved to be more efficient than other. One of the largest of these schemes ever carried out occurred in modern times in the United States, it was uncovered as recently as in late 2008. The man behind it managed to keep the scheme running for over 15 years in one of most monitored economic systems in the world. The man in charge of the operation, Bernard L. Madoff, got arrested for his scheme and pled guilty to the embezzling of billions of US dollars. It struck many as unimaginable how such a fraud could occur in an environment so carefully controlled by regulations and supervised by different institutions. The uncovering of the scheme rose questions on how this could go undetected for such a long time, and what could be done to avoid similar situations in the future. This report gives an insight on how the Madoff fraud was carried out, how it could go unnoticed for so long and if similar frauds could be prevented in the future. -

(212) 589-4201 Irving H. Picard Email: [email protected] David J

Baker & Hostetler LLP 45 Rockefeller Plaza New York, NY 10111 Telephone: (212) 589-4200 Facsimile: (212) 589-4201 Irving H. Picard Email: [email protected] David J. Sheehan Email: [email protected] Marc Hirschfield Email: [email protected] Alissa M. Nann Email: [email protected] Attorneys for Irving H. Picard, Esq. Trustee for the Substantively Consolidated SIPA Liquidation of Bernard L. Madoff Investment Securities LLC And Bernard L. Madoff UNITED STATES BANKRUPTCY COURT SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK SECURITIES INVESTOR PROTECTION Adv. Pro. No. 08-1789 (BRL) CORPORATION, Plaintiff-Applicant, SIPA Liquidation v. (Substantively Consolidated) BERNARD L. MADOFF INVESTMENT SECURITIES LLC, Defendant. In re: BERNARD L. MADOFF, Debtor. TRUSTEE’S SECOND INTERIM REPORT FOR THE PERIOD ENDING OCTOBER 31, 2009 300040417 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION...................................................................................................3 II. BACKGROUND.....................................................................................................5 A. PROCEDURAL HISTORY ..............................................................................5 B. MADOFF CHAPTER 7 LIQUIDATION .........................................................7 C. MSIL AND JOINT PROVISIONAL LIQUIDATORS ....................................8 D. CRIMINAL AND CIVIL CASES.....................................................................9 III. LIQUIDATION PROCEEDING...........................................................................15 -

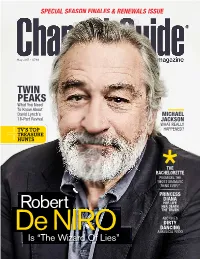

TWIN PEAKS What You Need to Know About David Lynch’S MICHAEL

Time-Sensitive SPECIAL SEASON FINALES & RENEWALS ISSUE PERIODICALS Channel Guide Class Publication Postmaster please deliver by the 1st of the month NAT magazine May 2017 • $7.99 TWIN PEAKS What You Need To Know About David Lynch’s MICHAEL channelguidemag.com 18-Part Revival JACKSON WHAT REALLY TV’S TOP HAPPENED? TREASURE HUNTS PREMIERING 5/9 ON DEMAND THE BACHELORETTE PROMISES THE “MOST DRAMATIC THING EVER!” PRINCESS DIANA HER LIFE HER DEATH Robert THE TRUTH ABC GIVES May 2017 May DIRTY DANCING De NIRO A MUSICAL REDO Is “The Wizard Of Lies” WATCH THE 10 MINUTE FREE PREVIEW SHORT LIST For More ReMIND magazine SEASON offers fresh takes on FINALE popular entertainment DATES We Break Down The Month’s See Page 8 from days gone by. Biggest And Best Programming So Each issue has dozens May You Never Miss A Must-See Minute. of brain-teasing 1 16 23 puzzles, trivia quizzes, Lucifer, FOX — New Episodes NCIS, CBS — Season Finale classic comics and Taken, NBC — Season Finale NCIS: New Orleans, CBS — Season Finale features from the 2 NBA: Western Conference Finals, The Mick, FOX — Season Finale Game 1, ESPN 1950s-1980s! Victorian Slum House, PBS Tracy Morgan: Staying Alive, N e t fl i x — New Series American Epic, PBS — New Series 17 < 5 Downward Dog, ABC — New Series Blue Bloods, CBS — Season Finale Downward Dog, ABC — Sneak Peek Bull, CBS — Season Finale The Mars Generation, N e t fl i x Criminal Minds: Beyond Borders, CBS The Flash, The CW — Season Finale Sense8, N e t fl i x — New Episodes — Season Finale NBA: Eastern Conference Finals, Brooklyn -

Report of Investigation Executive Summary

REPORT OF INVESTIGATION UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION OFFICE OF INSPECTOR GENERAL Case No. OIG-509 Investigation of Failure of the SEC To Uncover Bernard Madoff's Ponzi Scheme Executive Summary The OIG investigation did not find evidence that any SEC personnel who worked on an SEC examination or investigation of Bernard L. Madoff Investment Securities, LLC (BMIS) had any financial or other inappropriate connection with Bernard Madoff or the Madoff family that influenced the conduct of their examination or investigatory work. The OIG also did not find that former SEC Assistant Director Eric Swanson's romantic relationship with Bernard Madoffs niece, Shana Madoff, influenced the conduct of the SEC examinations of Madoff and his firm. We also did not find that senior officials at the SEC directly attempted to influence examinations or investigations of Madoff or the Madofffirm, nor was there evidence any senior SEC official interfered with the staffs ability to perform its work. The OIG investigation did find, however, that the SEC received more than ample information in the form of detailed and substantive complaints over the years to warrant a thorough and comprehensive examination and/or investigation of Bernard Madoff and BMIS for operating a Ponzi scheme, and that despite three examinations and two investigations being conducted, a thorough and competent investigation or examination was never performed. The OIG found that between June 1992 and December 2008 when Madoff confessed, the SEC received six! substantive complaints that raised significant red flags concerning Madoffs hedge fund operations and should have led to questions about whether Madoffwas actually engaged in trading. -

Bernard Madoff A

Brigham Young University Law School BYU Law Digital Commons Faculty Scholarship 12-31-2009 Evil Has a New Name (And a New Narrative): Bernard Madoff A. Christine Hurt BYU Law School, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.byu.edu/faculty_scholarship Part of the Banking and Finance Law Commons, and the Criminology and Criminal Justice Commons Recommended Citation A. Christine Hurt, ???? ??? ? ??? ???? (??? ? ??? ?????????): ??????? ??????, 2009 Mɪᴄʜ. Sᴛ. L. Rᴇᴠ. 947. This Symposium is brought to you for free and open access by BYU Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of BYU Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. EVIL HAS A NEW NAME (AND A NEW NARRATIVE): BERNARD MADOFF Christine Hurt* 2009 MICH. ST. L. REV. 947 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION .................................. ....... 947 I. MADOFF'S EXTRAORDINARY CRIME.........................951 A. The Rise and Fall of Bernard L. Madoff Investment Securities..951 B. Madoff's Scheme as Affinity Fraud ..................... 957 II. VICTIMS SHAPE THE MADOFF NARRATIVE ....................... 959 A. Victim Impact Statements ................... ......... 961 B. Sentencing "Extraordinary Evil " ............. ........... 965 C. Restitution, Remission, and Compensation ......... ...... 968 1. Restitution ....................................... 968 2. SIPC Compensation ............................ 969 3. Tax Relief ................ ................. -

Journal of American Studies the Madoff Paradox: American Jewish

Journal of American Studies http://journals.cambridge.org/AMS Additional services for Journal of American Studies: Email alerts: Click here Subscriptions: Click here Commercial reprints: Click here Terms of use : Click here The Madoff Paradox: American Jewish Sage, Savior, and Thief MICHAEL BERKOWITZ Journal of American Studies / Volume 46 / Issue 01 / February 2012, pp 189 202 DOI: 10.1017/S0021875811001423, Published online: 09 March 2012 Link to this article: http://journals.cambridge.org/abstract_S0021875811001423 How to cite this article: MICHAEL BERKOWITZ (2012). The Madoff Paradox: American Jewish Sage, Savior, and Thief. Journal of American Studies, 46, pp 189202 doi:10.1017/ S0021875811001423 Request Permissions : Click here Downloaded from http://journals.cambridge.org/AMS, IP address: 144.82.107.48 on 17 Oct 2012 Journal of American Studies, (), , – © Cambridge University Press doi:./S The Madoff Paradox: American Jewish Sage, Savior, and Thief MICHAEL BERKOWITZ Bernie Madoff perpetrated a Ponzi scheme on a scale that was gargantuan even compared with the outrageously destructive Enron and Worldcom debacles. A major aspect of the Madoff story is his rise as a specifically American Jewish type, who self-consciously exploited stereotypes to inspire trust and confidence in his counsel. Styling himself as a benefactor and protector of Jews as individuals and institutional Jewish interests, and possibly in the guise of the Jewish historical trope of shtadlan (intercessor), he was willing to threaten the well-being of all those enmeshed in his empire. The license granted to Madoff stemmed in part from the extent to which he appeared to diverge from earlier Jewish financial titans, such as Ivan Boesky and Michael Milken, in that he epitomized an absolute “insider”–as opposed to an “outsider” or marginal figure.