Scottish National Identity in the Works of James Kelman

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

From Alignment to Commitment: the Early Work of James Kelman

From Alignment to Commitment: The Early Work of James Kelman Terence Patrick Murphy James Kelman (© BBC, 2002) Abstract In Marxism and Literature (1977), Raymond Williams argues that writing is in an important sense always aligned. This sense of alignment, however, may be distinguished from a sense of chosen commitment,which is “conscious, active, and open.” Through a close analysis of the early work of the Scottish working-class writer James Kelman, this essay examines how an ideologically committed writer learned to refashion the dominant forms of novelistic discourse for his own political purposes. For Kelman, commitment in writing involves the recognition of the “distinction between dialogue and narrative as a summation of the political system.” This distinction was “simply another method of exclusion, of marginalizing and disenfranchising different peoples, cultures and communities,” Political commitment thus required Kelman to break successfully with the tradition of “‘working class authors’ who allowed ‘the voice’ of higher authority to control narrative, the place where the psychological drama occurred.” Copyright © 2007 by Terence Patrick Murphy and Cultural Logic, ISSN 1097-3087 Terence Patrick Murphy 2 . the relation between the language of the novelist — always in some measure an educated language, as it has to be if the full account is to be given, and the language of these newly described men and women — a familiar language, steeped in a place and in work; often different in profound as well as simple ways — and to the novelist consciously different — from the habits of education: the class, the method, the underlying sensibility. It isn’t only a matter of relating disparate idioms, though that technicality is how it often appears. -

NATIONAL IDENTITY in SCOTTISH and SWISS CHILDRENIS and YDUNG Pedplets BODKS: a CDMPARATIVE STUDY

NATIONAL IDENTITY IN SCOTTISH AND SWISS CHILDRENIS AND YDUNG PEDPLEtS BODKS: A CDMPARATIVE STUDY by Christine Soldan Raid Submitted for the degree of Ph. D* University of Edinburgh July 1985 CP FOR OeOeRo i. TABLE OF CONTENTS PART0N[ paos Preface iv Declaration vi Abstract vii 1, Introduction 1 2, The Overall View 31 3, The Oral Heritage 61 4* The Literary Tradition 90 PARTTW0 S. Comparison of selected pairs of books from as near 1870 and 1970 as proved possible 120 A* Everyday Life S*R, Crock ttp Clan Kellyp Smithp Elder & Cc, (London, 1: 96), 442 pages Oohanna Spyrip Heidi (Gothat 1881 & 1883)9 edition usadq Haidis Lehr- und Wanderjahre and Heidi kann brauchan, was as gelernt hatq ill, Tomi. Ungerar# , Buchklubg Ex Libris (ZOrichp 1980)9 255 and 185 pages Mollie Hunterv A Sound of Chariatst Hamish Hamilton (Londong 197ý), 242 pages Fritz Brunner, Feliy, ill, Klaus Brunnerv Grall Fi7soli (ZGricýt=970). 175 pages Back Summaries 174 Translations into English of passages quoted 182 Notes for SA 189 B. Fantasy 192 George MacDonaldgat týe Back of the North Wind (Londant 1871)t ill* Arthur Hughesp Octopus Books Ltd. (Londong 1979)t 292 pages Onkel Augusta Geschichtenbuch. chosen and adited by Otto von Grayerzf with six pictures by the authorg Verlag von A. Vogel (Winterthurt 1922)p 371 pages ii* page Alison Fel 1# The Grey Dancer, Collins (Londong 1981)q 89 pages Franz Hohlerg Tschipog ill* by Arthur Loosli (Darmstadt und Neuwaid, 1978)9 edition used Fischer Taschenbuchverlagg (Frankfurt a M99 1981)p 142 pages Book Summaries 247 Translations into English of passages quoted 255 Notes for 58 266 " Historical Fiction 271 RA. -

Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination

Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination Anglophone Writing from 1600 to 1900 Silke Stroh northwestern university press evanston, illinois Northwestern University Press www .nupress.northwestern .edu Copyright © 2017 by Northwestern University Press. Published 2017. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication data are available from the Library of Congress. Except where otherwise noted, this book is licensed under a Creative Commons At- tribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. In all cases attribution should include the following information: Stroh, Silke. Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination: Anglophone Writing from 1600 to 1900. Evanston, Ill.: Northwestern University Press, 2017. For permissions beyond the scope of this license, visit www.nupress.northwestern.edu An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libraries working with Knowledge Unlatched. KU is a collaborative initiative designed to make high-quality books open access for the public good. More information about the initiative and links to the open-access version can be found at www.knowledgeunlatched.org Contents Acknowledgments vii Introduction 3 Chapter 1 The Modern Nation- State and Its Others: Civilizing Missions at Home and Abroad, ca. 1600 to 1800 33 Chapter 2 Anglophone Literature of Civilization and the Hybridized Gaelic Subject: Martin Martin’s Travel Writings 77 Chapter 3 The Reemergence of the Primitive Other? Noble Savagery and the Romantic Age 113 Chapter 4 From Flirtations with Romantic Otherness to a More Integrated National Synthesis: “Gentleman Savages” in Walter Scott’s Novel Waverley 141 Chapter 5 Of Celts and Teutons: Racial Biology and Anti- Gaelic Discourse, ca. -

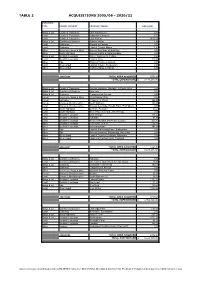

Table 2-Acquisitions (Web Version).Xlsx TABLE 2 ACQUISITIONS 2005/06 - 2020/21

TABLE 2 ACQUISITIONS 2005/06 - 2020/21 PURCHASE TYPE FOREST DISTRICT PROPERTY NAME AREA (HA) Bldgs & Ld Cowal & Trossachs Edra Farmhouse 2.30 Land Cowal & Trossachs Ardgartan Campsite 6.75 Land Cowal & Trossachs Loch Katrine 9613.00 Bldgs & Ld Dumfries & Borders Jufrake House 4.86 Land Galloway Ground at Corwar 0.70 Land Galloway Land at Corwar Mains 2.49 Other Inverness, Ross & Skye Access Servitude at Boblainy 0.00 Other North Highland Access Rights at Strathrusdale 0.00 Bldgs & Ld Scottish Lowlands 3 Keir, Gardener's Cottage 0.26 Land Scottish Lowlands Land at Croy 122.00 Other Tay Rannoch School, Kinloch 0.00 Land West Argyll Land at Killean, By Inverary 0.00 Other West Argyll Visibility Splay at Killean 0.00 2005/2006 TOTAL AREA ACQUIRED 9752.36 TOTAL EXPENDITURE £ 3,143,260.00 Bldgs & Ld Cowal & Trossachs Access Variation, Ormidale & South Otter 0.00 Bldgs & Ld Dumfries & Borders 4 Eshiels 0.18 Bldgs & Ld Galloway Craigencolon Access 0.00 Forest Inverness, Ross & Skye 1 Highlander Way 0.27 Forest Lochaber Chapman's Wood 164.60 Forest Moray & Aberdeenshire South Balnoon 130.00 Land Moray & Aberdeenshire Access Servitude, Raefin Farm, Fochabers 0.00 Land North Highland Auchow, Rumster 16.23 Land North Highland Water Pipe Servitude, No 9 Borgie 0.00 Land Scottish Lowlands East Grange 216.42 Land Scottish Lowlands Tulliallan 81.00 Land Scottish Lowlands Wester Mosshat (Horberry) (Lease) 101.17 Other Scottish Lowlands Cochnohill (1 & 2) 556.31 Other Scottish Lowlands Knockmountain 197.00 Other Tay Land at Blackcraig Farm, Blairgowrie -

Media Culture for a Modern Nation? Theatre, Cinema and Radio in Early Twentieth-Century Scotland

Media Culture for a Modern Nation? Theatre, Cinema and Radio in Early Twentieth-Century Scotland a study © Adrienne Clare Scullion Thesis submitted for the degree of PhD to the Department of Theatre, Film and Television Studies, Faculty of Arts, University of Glasgow. March 1992 ProQuest Number: 13818929 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 13818929 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 Frontispiece The Clachan, Scottish Exhibition of National History, Art and Industry, 1911. (T R Annan and Sons Ltd., Glasgow) GLASGOW UNIVERSITY library Abstract This study investigates the cultural scene in Scotland in the period from the 1880s to 1939. The project focuses on the effects in Scotland of the development of the new media of film and wireless. It addresses question as to what changes, over the first decades of the twentieth century, these two revolutionary forms of public technology effect on the established entertainment system in Scotland and on the Scottish experience of culture. The study presents a broad view of the cultural scene in Scotland over the period: discusses contemporary politics; considers established and new theatrical activity; examines the development of a film culture; and investigates the expansion of broadcast wireless and its influence on indigenous theatre. -

Representations of Scotland in Edwin Morgan's Poetry

California State University, San Bernardino CSUSB ScholarWorks Theses Digitization Project John M. Pfau Library 2002 Representations of Scotland in Edwin Morgan's poetry Theresa Fernandez Mendoza-Kovich Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd-project Part of the Literature in English, British Isles Commons Recommended Citation Mendoza-Kovich, Theresa Fernandez, "Representations of Scotland in Edwin Morgan's poetry" (2002). Theses Digitization Project. 2157. https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd-project/2157 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the John M. Pfau Library at CSUSB ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses Digitization Project by an authorized administrator of CSUSB ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. REPRESENTATIONS OF SCOTLAND IN EDWIN MORGAN'S POETRY A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in English Composition by Theresa Fernandez Mendoza-Kovich September 2002 REPRESENTATIONS OF SCOTLAND IN EDWIN MORGAN'S POETRY A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino by Theresa Fernandez Mendoza-Kovich September 2002 Approved by: Renee PrqSon, Chair, English Date Margarep Doane Cyrrchia Cotter ABSTRACT This thesis is an examination of the poetry of Edwin Morgan. It is a cultural analysis of Morgan's poetry as representation of the Scottish people. ' Morgan's poetry represents the Scottish people as determined and persistent in dealing with life's adversities while maintaining hope in a better future This hope, according to Morgan, is largely associated with the advent of technology and the more modern landscape of his native Glasgow. -

Diplomarbeit

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by OTHES DIPLOMARBEIT Titel der Diplomarbeit „Scottish National Identity: the Case of Irn Bru“ Verfasserin Stefanie Gattringer angestrebter akademischer Grad Magistra der Philosophie (Mag.phil.) Wien, 2012 Studienkennzahl lt. Studienblatt: A 343 Studienrichtung lt. Studienblatt: Anglistik und Amerikanistik Betreuerin: Assoz.-Prof. Mag. Dr. Susanne Reichl Acknowledgements I would like to thank my family and friends for their support during my studies and during the time I spend on writing this thesis. My gratitude goes especially to Eva H. for her valuable comments. Many thanks also go to my supervisor, Dr. Susanne Reichl, who enabled this research project and provided me with helpful feedback. Furthermore my gratitude goes to the Erasmus scholarship programme. The Erasmus scholarship enabled me to study at the University of Aberdeen and thus to enrich my academic life. It sparked my interest in Scotland and was the inspirational source for the topic of this thesis. I would like to dedicate this thesis to my parents, Renate and Stefan Gattringer, in order to thank them for their inestimable support and encouragement throughout the years. And the good thing is that as we arrive at a position where Scottishness, and especially Scottish identity, is neither perceived nor defined in any narrow way, we are no longer looking towards a series of ideas or symbols, far less searching for a hero, this kind of work is entirely suited to the spirit of the times, offering a sense of optimism and hope through experimentation and imaginative freedom that shows no sign of diminishing. -

AJ Aitken a History of Scots

A. J. Aitken A history of Scots (1985)1 Edited by Caroline Macafee Editor’s Introduction In his ‘Sources of the vocabulary of Older Scots’ (1954: n. 7; 2015), AJA had remarked on the distribution of Scandinavian loanwords in Scots, and deduced from this that the language had been influenced by population movements from the North of England. In his ‘History of Scots’ for the introduction to The Concise Scots Dictionary, he follows the historian Geoffrey Barrow (1980) in seeing Scots as descended primarily from the Anglo-Danish of the North of England, with only a marginal role for the Old English introduced earlier into the South-East of Scotland. AJA concludes with some suggestions for further reading: this section has been omitted, as it is now, naturally, out of date. For a much fuller and more detailed history up to 1700, incorporating much of AJA’s own work on the Older Scots period, the reader is referred to Macafee and †Aitken (2002). Two textual anthologies also offer historical treatments of the language: Görlach (2002) and, for Older Scots, Smith (2012). Corbett et al. eds. (2003) gives an accessible overview of the language, and a more detailed linguistic treatment can be found in Jones ed. (1997). How to cite this paper (adapt to the desired style): Aitken, A. J. (1985, 2015) ‘A history of Scots’, in †A. J. Aitken, ed. Caroline Macafee, ‘Collected Writings on the Scots Language’ (2015), [online] Scots Language Centre http://medio.scotslanguage.com/library/document/aitken/A_history_of_Scots_(1985) (accessed DATE). Originally published in the Introduction, The Concise Scots Dictionary, ed.-in-chief Mairi Robinson (Aberdeen University Press, 1985, now published Edinburgh University Press), ix-xvi. -

'A' That's Past Forget – Forgie': National Drama and the Construction of Scottish National Identity on the Nineteenth

Studies in Scottish Literature Volume 44 Article 5 Issue 2 Reworking Walter Scott 12-31-2018 ‘A’ that’s past forget – forgie’: National Drama and the Construction of Scottish National Identity on the Nineteenth-Century Stage Paula Sledzinska University of Aberdeen Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/ssl Part of the Literature in English, British Isles Commons, and the Theatre History Commons Recommended Citation Sledzinska, Paula (2019) "‘A’ that’s past forget – forgie’: National Drama and the Construction of Scottish National Identity on the Nineteenth-Century Stage," Studies in Scottish Literature: Vol. 44: Iss. 2, 37–50. Available at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/ssl/vol44/iss2/5 This Article is brought to you by the Scottish Literature Collections at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Studies in Scottish Literature by an authorized editor of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “A’ THAT’S PAST FORGET—FORGIE”: NATIONAL DRAMA AND THE CONSTRUCTION OF NATIONAL IDENTITY ON THE NINETEENTH-CENTURY STAGE Paula Sledzinska For centuries, theatre has provided a space for a discussion of social, cultural and political affairs. The link between theatre and politics is of a particularly critical kind, as it is often within the dramatic texts, and on the stage, that the turmoil of revolutionary transformations, historical tragedies, and future visions were portrayed or challenged, and the shapes and images of communities, or indeed nations, explored.1 The -

Gregory Burke's Black Watch

Scottish Polysyzygiacal Identity and Brian McCabe’s Short Fiction Jessica Aliaga-Lavrijseni Abstract Contemporary Scottish literature has increasingly involved complex negotiations between the different Scottish identities that have proliferated since the nineteen seventies and nineteen eighties. At the present time, the concept of identity postulated is no longer essentialist and monologic, like the one associated to the two halves of the traditional ’Caledonian antisyzygy’, but positional and relational, ’polysyzygiacal’, to use Stuart Kelly’s term. As this article shows, Brian McCabe’s short fiction explores Scottish identitarian issues from a renewed multifaceted and dialogic perspective, fostering an ongoing debate about what it means to be Scottish nowadays, and contributing to the diversification and pluralisation of literary representations of identity. Key words: polysyzygiacal identity, diversification, literary representations, Brian McCabe “A world is always as many worlds as it takes to make a world.” —Jean-Luc Nancy, Being Singular Plural (2000: 15) “I am rooted but I flow” —Michael, in V. Woolf’s The Waves (1977: 69) Introduction: The Genre of the Short Story in Scotland and the Caledonian Antisyzygy Contemporary Scottish literature has increasingly involved complex negotiations between the different Scottish identities that have proliferated since the nineteen seventies and nineteen eighties (March 2002: 1). Especially in the last decades of the twentieth century and the beginning of the twenty-first century, the (transmodern) conflicts triggered off by globalisation and glocalisation, as well as by the development of communication technologies, have further affected identity construction. But this whole process of the redefinition of identities has always been considered an ongoing process, since cultural identity is “a matter of becoming” (Hall 1993: 394). -

Class, Gender, and Identity in Contemporary Scottish Literature

UNIVERZITA PALACKÉHO V OLOMOUCI Filozofická fakulta Katedra anglistiky a amerikanistiky Jan Horáček James Kelman: Class, Gender, and Identity in Contemporary Scottish Literature Diplomová práce Anglická filologie – Historie Vedoucí práce: Mgr. Ema Jelínková, Ph.D. Olomouc 2012 Prohlašuji, že jsem tuto bakalářskou práci vypracoval samostatně a uvedl úplný seznam citované a použité literatury. V Olomouci dne 11. května 2012 ………………………………… James Kelman: Class, Gender, and Identity in Contemporary Scottish Literature iii 1 Contents Acknowledgements . v Introduction. 1 I Kelman and Capitalism . 5 1. ‘When skint I am a hulk’: Unemployment and Poverty-Stricken Freedom . 7 2. ‘these capitalist fuckers’: The Breakdown of Welfare . 10 3. ‘On the margins of the traditional working-class life’: Past and Present . 12 4. Stealing and Reading: New Perspectives on Workerism. 15 5. ‘wealthy fuckers and rich cunts’: Class War and Beyond . 18 6. ‘Places where humans might perish forever’: Victims and Casualties . 21 II Kelman and Working-Class Community . 25 7. ‘When men expect women to stop work’: Challenging Masculinity . 25 8. Emasculated Men and Empowered Women . 29 9. ‘Middle-Class Wankers’: From Ambivalence to Estrangement . 32 10. The Collapse of Workers’ Solidarity . 34 III Kafka on the Clyde . 38 11. ‘Wee horrors’: Authentic Stories and Abnormal Events . 38 12. Concrete Facts and Genre Fiction . 41 13. Lack and Becoming: Changing Kelman? . 44 IV Kelman and Demotic Language . 48 14. Unity of Language: The Clash Between English and Scots Vernacular . 49 15. ‘ah jist open ma mooth and oot it comes’: Language of the Gutter . 53 16. Abrogation: Resisting Power and Cultural Marginalization . 56 17. ‘enerfuckinggetic’: Language Play and Innovation . -

1 Sarah Sharp Exporting 'The Cotter's Saturday Night': Robert Burns

1 Sarah Sharp Exporting ‘The Cotter’s Saturday Night’: Robert Burns, Scottish Romantic Nationalism and Colonial Settler Identity Abstract: A Scottish literary icon of the nineteenth century, Burns’s ‘The Cotter’s Saturday Night’ was a key component of the cultural baggage carried by emigrant Scots seeking a new life abroad. The myth of the thrifty, humble and pious Scottish cottager is a recurrent figure in Scottish colonial writing whether that cottage is situated in the South African veld or the Otago bush. This article examines the way in which Burns’s cotter informed the myth of the self-sufficient Scottish peasant in the poetry of John Barr and Thomas Pringle. It will argue that, just as ‘The Cotter’ could be used to reinforce a particular set of ideas about Scottish identity at home, Scottish settlers used Burns’s poem to respond to and cement new identities abroad. Keywords: Scottish Romanticism, Settler Colonialism, Robert Burns, Thomas Pringle, John Barr, John Wilson. 2 Exporting ‘The Cotter’s Saturday Night’: Robert Burns, Scottish Romantic Nationalism and Colonial Settler Identity. In 1787, reviewer John Logan commented of Robert Burns’s Kilmarnock edition that ‘“The Cotter’s Saturday Night” is, without exception, the best poem in the collection’.1 His opinion was echoed by many contemporary and subsequent reviewers. In 1812 George Gleig was able to confidently assert that ‘The “Saturday Night” is indeed universally felt as the most interesting of all the author’s poems’ (Bold, 217). This view of Burns’s poem of common life has not endured. The image of Scotland presented in the poem has become at best a stereotype and at worst a source of cultural cringe.