Towards a Postcolonial Pedagogy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

AKLF-2018-Schedule

AKLF 2018 is here! Welcome to Apeejay Kolkata Literary Festival 2018! The internationally renowned and eagerly awaited Apeejay Kolkata Literary Festival (AKLF) welcomes you back to the St. Paul’s Cathedral lawns. A non-prot initiative free for everyone, AKLF is the only literary festival to have emerged from a bookstore - the iconic 98 year old Oxford Bookstore. The upcoming 9th edition of AKLF is poised to scale new heights, with a meticulously curated programme, bringing the world and the nation to Kolkata. Speakers from across the globe, from Australia, UK, Scotland, France, Germany, Haiti and more. Join eminent novelists, lmmakers, artists, poets, and social commentators to bring you a heady mix of literature, arts and current affairs. This year we collaborate with Bonjour India, the prestigious French initiative across Literature and the Arts, as well as leading international festivals, Edinburgh International Book Festival and Henley Literary Festival, to present exciting programs; and reaffirm our link with the Jaipur Literature Festival through our exclusive Oxford Bookstore Book Cover Prize. We offer a bigger and better Oxford Junior Literary Festival (OJLF) for young readers; announce a major new award for emerging women writers; bring you an array of India’s top poets at Poetry Café; and introduce Mind Your Own Business, a B2B segment for students and young professionals. Come join us! VENUES - St. Paul’s Cathedral 1A, Cathedral Road, Kolkata – 71 Goethe Institute, Max Mueller Bhavan 57 A Park Street, Park Mansions, Gate 4, Kolkata, West Bengal 700016 Tollygunge Club 120, Deshapran Sasmal Road, Saha Para, Tollygunge Golf Club, Tollygunge, Kolkata West Bengal 700033 Harrington Street Arts Centre 8, Ho Chi Minh Sarani, (opp The American Consulate, next to ICCR), Suite No. -

KRAKAUER-DISSERTATION-2014.Pdf (10.23Mb)

Copyright by Benjamin Samuel Krakauer 2014 The Dissertation Committee for Benjamin Samuel Krakauer Certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Negotiations of Modernity, Spirituality, and Bengali Identity in Contemporary Bāul-Fakir Music Committee: Stephen Slawek, Supervisor Charles Capwell Kaushik Ghosh Kathryn Hansen Robin Moore Sonia Seeman Negotiations of Modernity, Spirituality, and Bengali Identity in Contemporary Bāul-Fakir Music by Benjamin Samuel Krakauer, B.A.Music; M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin May 2014 Dedication This work is dedicated to all of the Bāul-Fakir musicians who were so kind, hospitable, and encouraging to me during my time in West Bengal. Without their friendship and generosity this work would not have been possible. জয় 巁쇁! Acknowledgements I am grateful to many friends, family members, and colleagues for their support, encouragement, and valuable input. Thanks to my parents, Henry and Sarah Krakauer for proofreading my chapter drafts, and for encouraging me to pursue my academic and artistic interests; to Laura Ogburn for her help and suggestions on innumerable proposals, abstracts, and drafts, and for cheering me up during difficult times; to Mark and Ilana Krakauer for being such supportive siblings; to Stephen Slawek for his valuable input and advice throughout my time at UT; to Kathryn Hansen -

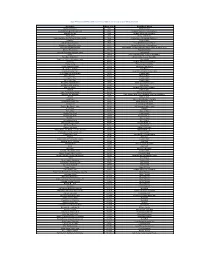

Convert JPG to PDF Online

Withheld list SL # Roll No 1 12954 2 00220 3 00984 4 05666 5 00220 6 12954 7 00984 8 05666 9 21943 10 06495 11 04720 1 SL# ROLL Name Father Marks 1 00002 MRINALINI DEY PARIJAT KUSUM PATWARY 45 2 00007 MD. MOHIUL ISLAM LATE. MD. NURUL ISLAM 43 3 00008 MD. SALAM KHAN RUHUL AMIN KHAN 40 4 00014 SYED AZAZUL HAQUE SAYED FAZLE HAQUE 40 5 00016 ROMANCE BAIDYA MILAN KANTI BAIDYA 51 6 00018 DIPAYAN CHOWDHURY SUBODH CHOWDHURY 40 7 00019 MD. SHAHIDUL ISLAM MD. ABUL HASHEM 47 8 00021 MD. MASHUD-AL-KARIM SAHAB UDDIN 53 9 00023 MD. AZIZUL HOQUE ABDUL HAMID 45 10 00026 AHSANUL KARIM REZAUL KARIM 54 11 00038 MOHAMMAD ARFAT UDDIN MOHAMMAD RAMZU MIAH 65 12 00039 AYON BHATTACHARJEE AJIT BHATTACHARJEE 57 13 00051 MD. MARUF HOSSAIN MD. HEMAYET UDDIN 43 14 00061 HOSSAIN MUHAMMED ARAFAT MD. KHAIRUL ALAM 42 15 00064 MARJAHAN AKTER HARUN-OR-RASHED 45 16 00065 MD. KUDRAT-E-KHUDA MD. AKBOR ALI SARDER 55 17 00066 NURULLAH SIDDIKI BHUYAN MD. ULLAH BHUYAN 46 18 00069 ATIQUR RAHMAN OHIDUR RAHMAN 41 19 00070 MD. SHARIFUL ISLAM MD. ABDUR RAZZAQUE (LATE) 46 20 00072 MIZANUR RAHMAN JAHANGIR HOSSAIN 49 21 00074 MOHAMMAD ZIAUDDIN CHOWDHURY MOHAMMAD BELAL UDDIN CHOWDHURY 55 22 00078 PANNA KUMAR DEY SADHAN CHANDRA DEY 47 23 00082 WAYES QUADER FAZLUL QUDER 43 24 00084 MAHBUBUR RAHMAN MAZEDUR RAHMAN 40 25 00085 TANIA AKTER LATE. TAYEB ALI 51 26 00087 NARAYAN CHAKRABORTY BUPENDRA KUMER CHAKRABORTY 40 27 00088 MOHAMMAD MOSTUFA KAMAL SHAMSEER ALI 55 28 00090 MD. -

“Do-Re-Mi-Fa-So-La, It's Not Precise”: Tracking the 'Demurral' in the Bengali Lebensmusik of The

Rupkatha Journal on Interdisciplinary Studies in Humanities (ISSN 0975-2935), Vol. 10, No. 3, 2018 [Indexed by Web of Science, Scopus & approved by UGC] DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.21659/rupkatha.v10n3.16 Full Text: http://rupkatha.com/V10/n3/v10n316.pdf “Do-re-mi-fa-so-la, it’s not precise”: tracking the ‘demurral’ in the Bengali Lebensmusik of the 90s Dibyakusum Ray1 & Amlan Baisya2 1Asst. Professor, Dept. of Humanities and Social Sciences, IIT Ropar [email protected]. Orcid: 0000-0002-9537-3277 2PhD Research Scholar, Dept. of HSS, NIT Silchar [email protected] Orcid: 0000-0002-5966-1108 Abstract This paper is on four song-texts from Kabir Suman, Nachiketa Chakraborty, Silajit Majumder and Anjan Dutt—the apostles of ‘Jibonmukhee’ Bengali songs in early 90s-- as a form of cultural negotiation with the changing political-social-economic milieu within the country. Set in the backdrop of economic liberalization, rise of right-wing Hindutva nationalism and a strong left regime in the state for more than a decade, Bengal in the 90s reacted to the vista of ‘change’ in myriad ways—‘Culture’ being one and ‘Jibonmukhee’ being instantaneously vocal within it, the four harbingers of the new language of ‘culture’— in four of their seminal texts arranged thematically and chronologically |1992-1995|-- show an ideological demurral of the urban, middle class Bengali intelligentsia in reacting to ‘change’—the ‘old’ is repudiated, the ‘new’ unacceptable. ‘Jibonmukhee’ posits a dilemma unique to Bengali literati: the journey from celebration→ trepidation→ rejection unhesitatingly culminates in escape: an escape from ‘what-could- have-been’ and not a refuge in ‘what-will-be’. -

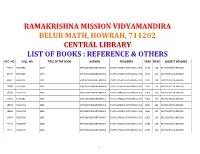

Ramakrishna Mission Vidyamandira Belur Math, Howrah, 711202 Central Library List of Books : Reference & Others Acc

RAMAKRISHNA MISSION VIDYAMANDIRA BELUR MATH, HOWRAH, 711202 CENTRAL LIBRARY LIST OF BOOKS : REFERENCE & OTHERS ACC. NO. CALL. NO. TITLE OF THE BOOK AUTHOR PUBLISHER YEAR PRICE SUBJECT HEADING 44638 R032/ENC 1978 ENYCOLPAEDIA BRITANNICA ENCYCLOPAEDIA BRITANNICA, ING 1978 150 ENCYCLOPEDIA-ENGLISH 44639 R032/ENC 1979 ENYCOLPAEDIA BRITANNICA ENCYCLOPAEDIA BRITANNICA, ING 1979 100 ENCYCLOPEDIA-ENGLISH 44641 R-032/BRI 1981 ENYCOLPAEDIA BRITANNICA ENCYCLOPEADIA BRITANNICA, INC 1981 100 ENCYCLOPEDIA-ENGLISH 15648 R-032/BRI 1982 ENYCOLPAEDIA BRITANNICA ENCYCLOPAEDIA BRITANNICA, ING 1982 100 ENCYCLOPEDIA-ENGLISH 15649 R-032/ENC 1983 ENYCOLPAEDIA BRITANNICA ENCYCLOPAEDIA BRITANNICA, ING 1983 100 ENCYCLOPEDIA-ENGLISH 17913 R032/ENC 1984 ENYCOLPAEDIA BRITANNICA ENCYCLOPAEDIA BRITANNICA, ING 1984 350 ENCYCLOPEDIA-ENGLISH 18648 R-032/ENC 1985 ENYCOLPAEDIA BRITANNICA ENCYCLOPAEDIA BRITANNICA, ING 1985 100 ENCYCLOPEDIA-ENGLISH 18786 R-032/ENC 1986 ENYCOLPAEDIA BRITANNICA ENCYCLOPAEDIA BRITANNICA, ING 1986 100 ENCYCLOPEDIA-ENGLISH 19693 R-032/ENC 1987 ENYCOLPAEDIA BRITANNICA ENCYCLOPEADIA BRITANNICA, INC 1987 100 ENCYCLOPEDIA-ENGLISH 21140 R-032/ENC 1988 ENYCOLPAEDIA BRITANNICA ENCYCLOPEADIA BRITANNICA, INC 1988 100 ENCYCLOPEDIA-ENGLISH 21141 R-032/ENC 1989 ENYCOLPAEDIA BRITANNICA ENCYCLOPEADIA BRITANNICA, INC 1989 100 ENCYCLOPEDIA-ENGLISH 1 ACC. NO. CALL. NO. TITLE OF THE BOOK AUTHOR PUBLISHER YEAR PRICE SUBJECT HEADING 21426 R-032/ENC 1990 ENYCOLPAEDIA BRITANNICA ENCYCLOPAEDIA BRITANNICA, ING 1990 150 ENCYCLOPEDIA-ENGLISH 21797 R-032/ENC 1991 ENYCOLPAEDIA -

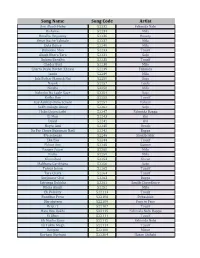

SONG CODE and Send to 4000 to Set a Song As Your Welcome Tune

Type WT<space>SONG CODE and send to 4000 to set a song as your Welcome Tune Song Name Song Code Artist/Movie/Album Aaj Apchaa Raate 5631 Anindya N Upal Ami Pathbhola Ek Pathik Esechhi 5633 Hemanta Mukherjee N Asha Bhosle Andhakarer Pare 5634 Somlata Acharyya Chowdhury Ashaa Jaoa 5635 Boney Chakravarty Auld Lang Syne And Purano Sei Diner Katha 5636 Shano Banerji N Subhajit Mukherjee Badrakto 5637 Rupam Islam Bak Bak Bakam Bakam 5638 Priya Bhattacharya N Chorus Bhalobese Diganta Diyechho 5639 Hemanta Mukherjee N Asha Bhosle Bhootader Bechitranusthan 56310 Dola Ganguli Parama Banerjee Shano Banerji N Aneek Dutta Bhooter Bhobishyot 56312 Rupankar Bagchi Bhooter Bhobishyot karaoke Track 56311 Instrumental Brishti 56313 Anjan Dutt N Somlata Acharyya Chowdhury Bum Bum Chika Bum 56315 Shamik Sinha n sumit Samaddar Bum Bum Chika Bum karaoke Track 56314 Instrumental Chalo Jai 56316 Somlata Acharyya Chowdhury Chena Chena 56317 Zubeen Garg N Anindita Chena Shona Prithibita 56318 Nachiketa Chakraborty Deep Jwele Oi Tara 56319 Asha Bhosle Dekhlam Dekhar Par 56320 Javed Ali N Anwesha Dutta Gupta Ei To Aami Club Kolkata Mix 56321 Rupam Islam Ei To Aami One 56322 Rupam Islam Ei To Aami Three 56323 Rupam Islam Ei To Aami Two 56324 Rupam Islam Ek Jhatkay Baba Ma Raji 56325 Shaan n mahalakshmi Iyer Ekali Biral Niral Shayane 56326 Asha Bhosle Ekla Anek Door 56327 Somlata Acharyya Chowdhury Gaanola 56328 Kabir Suman Hate Tomar Kaita Rekha 56329 Boney Chakravarty Jagorane Jay Bibhabori 56330 Kabir Suman Anjan Dutt N Somlata Acharyya Chowdhury Jatiswar 56361 -

NEW ADDITIONS to PARLIAMENT LIBRARY English 000

NEW ADDITIONS TO PARLIAMENT LIBRARY English 000 GENERALITIES 1 Glenday, Craig, ed. Guinness world records 2015 / edited by Craig Glenday.-- London: Guinness World Records, 2014. 255p.: plates: illus.; 30cm. ISBN : 978-1-908843-62-3. R 032.02 GUI B209081,Ref. Price : PD ****18.00 2 Ray, Kabita Public health in rural Bengal during the colonial period, 1921-1947: selections from journals and newspapers / Kabita Ray.-- Kolkata: Papyrus, 2012. 224p.; 22cm. Bilingual: English-Bengali. ISBN : 978-81-908360-9-8. 070.4493621095423 KAB-b C73446 Price : RS.***300.00 3 Abdul Kalam, A.P.J. Forge your future / A.P.J. Abdul Kalam.--rev.ed.-- New Delhi: Rajpal, 2014. 223p.: plates; 22cm. ISBN : 978-93-5064-279-5. 080 ABD-f B209108 Price : RS.***250.00 4 Bagchi, Subroto Zen garden: conversations with pathmakers / Subroto Bagchi.-- New Delhi: Portfolio, 2013. xiv, 328p.; 21cm. ISBN : 9780670087051. 080 BAG-z C73417; C75380 Price : RS.***499.00 5 Rao, N. Meera Raghavendra Slice of life / N. Meera Raghavendra Rao.-- Chennai: Palaniappa Brothers, 2012. 226p. ; 24cm. ISBN : 978-81-8379-586-9. 080 MEE-s C73414 Price : RS.***200.00 6 Narasiah, K.R.A. Lettered dialogue: correspondence between Krithika and Chitti / Selection and commentary by K.R.A. Narasiah.-- Chennai: Palaniappa Brothers, 2012. 235p.; 21cm. ISBN : 978-81-8379-565-4. 080 NAR-l C73407 Price : RS.***175.00 7 Rangan, Baradwaj Conversations with Mani Ratnam / Baradwaj Rangan with a foreword by A.R. Rahman.-- New Delhi: Penguin Books, 2013 xxi, 327p.: plates; 23cm. First published in 2012 by Viking. ISBN : 978-0-143-42110-8. -

Bengali Sentimental Booklet

BENGALI SENTIMENTAL - 200 SONGS 10. Balukabelay Kurai Jhinuk Album: All Time Greats - 01. Duti Pakhi Duti Teere Satinath Mukherjee Album: Songs To Remember Artiste: Satinath Mukherjee Artiste: Talat Mahmood Lyricist: Gauriprasanna Mazumder Lyricist: Girin Chakraborty Music Director: Satinath Mukherjee Music Director: Kamal Dasgupta 11. Emon Din Aaste Pare 02. Adho Raate Jodi Ghum Bhenge Album: Chayanika Album: Sera Shilpi Sera Gaan Volume 6 Artiste: Shyamal Mitra Artiste: Talat Mahmood Lyricist: Gauriprasanna Mazumder Lyricist: Anil Bhattacharya Music Director: Shyamal Mitra Music Director: Nirmal Bhattacharya 12. Hoyto Kichhui Nahi Pabo 03. Hay Hay Go Raat Jay Go Album: Solid Gold – Shyamal Mitra Album: Chayanika Artiste: Sandhya Mukherjee Artiste: Manna Dey Lyricist: Gauriprasanna Mazumder Lyricist: Gauriprasanna Mazumder Music Director: Shyamal Mitra Music Director: Manna Dey 13. Srimati Je Kande 04. Chithi (Tumi Aaj Kato Durey) Album: Chayanika Gems From Bengal Album: Jaganmoy Mitra - Volume 2 Tumi Ki Ekhono Artiste: Malay Mukherjee Artiste: Jaganmoy Mitra Lyricist: Miltoo Ghosh Lyricist: Pronab Roy Music Director: Sailen Mukherjee Music Director: Subal Dasgupta 14. Kato Nishi Gechhe Nidhara 05. Aar Kato Rohibo Sudhu Path Album: Sera Shilpi Sera Gaan, Vol 4 Album: Katha Koyo Naako Shudhu Sono Artiste: Lata Mangeshkar Artiste: Hemanta Mukherjee Lyricist: Pabitra Mitra Lyricist: Gauriprasanna Mazumder Music Director: Satinath Mukherjee Music Director: Satinath Mukherjee 15. Aakash Pradip Jwale 06. Ogo Mor Geetimoy Album: Sera Shilpi Sera Gaan, Vol 4 Album: Chayanika Artiste: Lata Mangeshkar Artiste: Sandhya Mukherjee Lyricist: Pabitra Mitra Lyricist: Kamal Ghosh Music Director: Satinath Mukherjee Music Director: Robin Chatterjee 16. Tumi Aar Deko Na 07. Ami Chole Gele Pashaner Buke Album: Hits Of Manna Dey Volume 2 Album: All Time Greats - Artiste: Manna Dey Satinath Mukherjee Lyricist: Gauriprasanna Mazumder Artiste: Satinath Mukherjee Music Director: Manna Dey Lyricist: Shyamal Gupta 17. -

Author Name Name of the Book Book Link Sub-Section Uploader ? A

Watermark Author Name Name of the Book Book Link Sub-Section Uploader ? A http://bengalidownload.com/index. php/topic/15177-bidesher-nisiddho- Bidesher Nisiddho Uponyas (3 volumes) uponyas-3-volumes/ Anubad Peter NO http://bengalidownload.com/index. Abadhut Fokkod Tantram php/topic/12191-fokkodtantramrare-book/ Exclusive Books & Others মানাই http://bengalidownload.com/index. Abadhut Morutirtho Hinglaj php/topic/9251-morutirtho-hinglaj-obodhut/ Others Professor Hijibijbij http://bengalidownload.com/index. php/topic/3987-a-rare-poem-by- Abanindranath Thakur A rare poem by Abaneendranath Tagore abaneendranath-tagore/ Kobita SatyaPriya http://bengalidownload.com/index. Abanindranath Thakur rachonaboli - Part 1 & php/topic/5937-abanindranath-thakur- Abanindranath Thakur 2 rachonaboli/ Rachanaboli dbdebjyoti1 http://bengalidownload.com/index. php/topic/12517-alor-fulki-by- Abanindranath Thakur Alor Fulki abanindranath-thakur/ Uponyas anku http://bengalidownload.com/index. php/topic/12517-alor-fulki-by- Abanindranath Thakur Alor Fulki abanindranath-thakur/ Uponash Anku No http://bengalidownload.com/index. php/topic/5840-buro-angla-by- abanindranath-thakur-bd-exclusive-links- Abanindranath Thakur Buro Angla added/ Uponash dbdebjyoti1 YES http://bengalidownload.com/index. php/topic/14636-choiton-chutki- abanindranath-thakur-53-pages-134-mb- Abanindranath Thakur Choiton Chutki pdf-arb/ Choto Golpo ARB NO http://bengalidownload.com/index. Abanindranath Thakur Khirer Putul php/topic/6382-khirer-putul/ Uponash Gyandarsi http://bengalidownload.com/index. php/topic/6379-pothe-bipothe- কঙ্কালিমাস Abanindranath Thakur Pothe Bipothe abanindranath-thakur/ Uponyas করোটিভূষণ http://bengalidownload.com/index. php/topic/5937-abanindranath-thakur- Abanindranath Thakur Rachonaboli rachonaboli/ Rachanaboli dbdebjyoti1 http://bengalidownload.com/index. php/topic/6230-shakuntala-abanindranath- Abanindranath Thakur Shakuntala tagore/ Choto Golpo Huloo Don http://bengalidownload.com/index. -

Annual Report 2009-2010

Annual Report NDIA NTERNATIONAL ENTRE I I I C -2010 ND 2009 I A I NTERNAT I ONAL C ENTRE Annual Report Annual 2009 INDIA INTERNATIONAL CENTRE -2010 40 Max Mueller Marg New Delhi 110 003 INDIA INTERNATIONAL CENTRE New Delhi Annual Report INDIA INTERNATIONAL CENTRE 2009-2010 INDIA INTERNATIONAL CENTRE New Delhi Board of Trustees Professor M.G.K. Menon, President Justice B. N. Srikrishna Dr. Kapila Vatsyayan Mr. L. K. Joshi Mr. Soli J. Sorabjee Professor S.K. Thorat Mr. N. N. Vohra Dr. Kavita A. Sharma Executive Members Dr. Kavita A. Sharma, Director Prof. Rajasekharan Pillai Mr. Kisan Mehta Dr. K.T. Ravindran Mr. Keshav N. Desiraju Mr. M.P. Wadhawan, Hon. Treasurer Lt. Gen. V.R. Raghavan Cmde. (Retd.) Ravinder Datta, Secretary Mr. Vipin Malik Finance Committee Dr. Shankar N. Acharya, Chairman Mr. M.P. Wadhawan, Hon. Treasurer Mr. Pradeep Dinodia, Member Mr. P.R. Sivasubramanian, Chief Finance Officer Lt. Gen. (Retd.) V.R. Raghavan, Member Cmde. (Retd.) Ravinder Datta, Secretary Dr. Kavita A. Sharma, Director Medical Consultants Dr. K.P. Mathur Dr. Rita Mohan Dr. K.A. Ramachandran Dr. B. Chakravorty Dr. Mohammad Qasim IIC Senior Staff Ms. Premola Ghose, Chief Programme Division Mr. A.L. Rawal, Dy. General Manager (C) Mr. Arun Potdar, Chief Maintenance Division Mrs. Shamole Aggarwal, Dy. General Manager (H) Mrs. Ira Pande, Chief Editor Mr. Inder Butalia, Sr. Finance and Accounts Officer Mr. Amod K. Dalela, Administration Officer Mrs. Sushma Zutshi, Librarian Mr. Vijay Kumar Thukral, Executive Chef Mr. K.S. Kutty, Membership Officer -2010 Annual Report 2009 It is my privilege to present the forty-ninth Annual Report of the India International Centre for the year commencing 1 February, 2009 and ending on 31 January, 2010. -

Song Name Song Code Artist

Song Name Song Code Artist Ami Akash Hobo 52232 Fahmida Nabi Bishshas 52234 Mila Bondhu Doyamoy 52236 Beauty Bristi Nache Taletale 52237 Mila Dola Dance 52240 Mila Bishonno Mon 52233 Tausif Akash Bhora Tara 52231 Saju Bolona Bondhu 52235 Tausif Chader Buri 52238 Mila Charta Deyal Hothat Kheyal 52239 Fahmida Jaadu 52249 Mila Jala Bojhar Manush Nai 52250 Saju Nayok 52257 Leela Nirobe 52258 Mila Kolonko Na Lagle Gaye 52254 Saju Kotha Dao 52255 Tausif Kay Aankay Onno Schobi 52251 Tahsan Sokhi Bologo Amay 52262 Saju Hobo Dujon Sathi 52247 Fahmida Bappa Ei Mon 52243 Oni Doyal 52241 Ovi Hoyto Ami 52248 Ornob Du Par Chuya Bohoman Nadi 52242 Bappa Eto sohosay 52246 Shakib Jakir Eka Eka 52244 Tausif Ekhon Ami 52245 Sumon Paaper Pujari 52260 Mila Nisha 52259 Mila Khunshuti 52253 Shuvo Malikana Garikhana 52256 Saju Tomar Jonno 52265 Tausif Tare Chara 52264 Tausif Surjosane Chol 52263 Bappa Satranga Dukkha 52261 Sanjib Chowdhury Khola Akash 52252 Mila Ek Polokey 522113 Tausif Bondhur Prem 522106 Debashish Dhrubotara 522109 Face to Face Bristi 2 522107 Tausif Hate Deo Rakhi 522115 Fahmida Nobi Bappa Ei Jibon 522111 Tausif Ek Mutho Gaan 522112 Fahmida Nobi Ek Tukro Megh 522114 Tausif Danpite 522108 Minar Kurbani Kurbani 522304 Hasan Shihabi Premchara Cholena Duniya 522342 Saju Rodela Dupur 522348 Tahsan Mithila Jeona Durey Chole 522280 Bappa Toni Khachar Bhitor Ochin Pakhi 522291 Labonno Kumari 522303 Shohor Bondi Nach mayuri nach re 522341 Labonno Tumi Amar 522381 Shahed Chandkumari 522385 Purno Soilo Soi 522391 Purno Itihas 71 522534 ROCK 404 Chandrabindu -

Of Contemporary India

OF CONTEMPORARY INDIA Catalogue Of The Papers of Girish Karnad Plot # 2, Rajiv Gandhi Education City, P.O. Rai, Sonepat – 131029, Haryana (India) 1 Girish Karnad (1938-2019) A renowned Kannada playwright, author, actor and film director, Girish Karnad was born on 19 May 1938 at Matheran, Bombay Presidency (now Maharashtra). After graduating from Karnataka University in 1958, Girish Karnad studied philosophy, politics, and economics as a Rhodes Scholar at the University of Oxford (1960–63). After his return to India, Girish Karnad started working with the Oxford University Press in Chennai, 1963, resigned in 1970 to devote full time to writing. At the young age of 35, he became the Director of the Film and the Television Institute of India, Pune (1974–1975), was also its Chairman (1999-2001). He was a visiting Professor at the University of Chicago, 1987–88. He served as the Chairman of the Sangeet Natak Akademi (1988–93), and the Director of the Nehru Centre, London (2000–2003). Girish Karnad started his career in acting and screenwriting in a Kannada movie, Samskara (1970) and acted in more than 50 films including Hindi and other regional languages. The notable among them are Vamsha Vriksha, Swami, Manthan, Nishant, Ahista Ahista, Nagamandala, Sankeerthana, Dharam Chakram, Hey Ram, Iqbal, China Gate, Pukar, Ek Tha Tiger and Tiger Zinda Hai. He played the role of Swami‟s father in the popular TV serial „Malgudi Days‟. Girish Karnad has been a recipient of several National Filmfare Awards -- Best Director and Best Screenplay. He was honoured with the Padma Shri in 1972, Padma Bhushan in 1992 and Jnanpith Award in 1999.