“Do-Re-Mi-Fa-So-La, It's Not Precise”: Tracking the 'Demurral' in the Bengali Lebensmusik of The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ANNIVERSARY SPECIAL Millenniumpost.In

ANNIVERSARY SPECIAL millenniumpost.in pages millenniumpost NO HALF TRUTHS th28 NEW DELHI & KOLKATA | MAY 2018 Contents “Dharma and Dhamma have come home to the sacred soil of 63 Simplifying Doing Trade this ancient land of faith, wisdom and enlightenment” Narendra Modi's Compelling Narrative 5 Honourable President Ram Nath Kovind gave this inaugural address at the International Conference on Delineating Development: 6 The Bengal Model State and Social Order in Dharma-Dhamma Traditions, on January 11, 2018, at Nalanda University, highlighting India’s historical commitment to ethical development, intellectual enrichment & self-reformation 8 Media: Varying Contours How Central Banks Fail am happy to be here for 10 the inauguration of the International Conference Unmistakable Areas of on State and Social Order 12 Hope & Despair in IDharma-Dhamma Traditions being organised by the Nalanda University in partnership with the Vietnam The Universal Religion Buddhist University, India Foundation, 14 of Swami Vivekananda and the Ministry of External Affairs, Government of India. In particular, Ethical Healthcare: A I must welcome the international scholars and delegates, from 11 16 Collective Responsibility countries, who have arrived here for this conference. Idea of India I understand this is the fourth 17 International Dharma-Dhamma Conference but the first to be hosted An Indian Summer by Nalanda University and in the state 18 for Indian Art of Bihar. In a sense, the twin traditions of Dharma and Dhamma have come home. They have come home to the PMUY: Enlightening sacred soil of this ancient land of faith, 21 Rural Lives wisdom and enlightenment – this land of Lord Buddha. -

AKLF-2018-Schedule

AKLF 2018 is here! Welcome to Apeejay Kolkata Literary Festival 2018! The internationally renowned and eagerly awaited Apeejay Kolkata Literary Festival (AKLF) welcomes you back to the St. Paul’s Cathedral lawns. A non-prot initiative free for everyone, AKLF is the only literary festival to have emerged from a bookstore - the iconic 98 year old Oxford Bookstore. The upcoming 9th edition of AKLF is poised to scale new heights, with a meticulously curated programme, bringing the world and the nation to Kolkata. Speakers from across the globe, from Australia, UK, Scotland, France, Germany, Haiti and more. Join eminent novelists, lmmakers, artists, poets, and social commentators to bring you a heady mix of literature, arts and current affairs. This year we collaborate with Bonjour India, the prestigious French initiative across Literature and the Arts, as well as leading international festivals, Edinburgh International Book Festival and Henley Literary Festival, to present exciting programs; and reaffirm our link with the Jaipur Literature Festival through our exclusive Oxford Bookstore Book Cover Prize. We offer a bigger and better Oxford Junior Literary Festival (OJLF) for young readers; announce a major new award for emerging women writers; bring you an array of India’s top poets at Poetry Café; and introduce Mind Your Own Business, a B2B segment for students and young professionals. Come join us! VENUES - St. Paul’s Cathedral 1A, Cathedral Road, Kolkata – 71 Goethe Institute, Max Mueller Bhavan 57 A Park Street, Park Mansions, Gate 4, Kolkata, West Bengal 700016 Tollygunge Club 120, Deshapran Sasmal Road, Saha Para, Tollygunge Golf Club, Tollygunge, Kolkata West Bengal 700033 Harrington Street Arts Centre 8, Ho Chi Minh Sarani, (opp The American Consulate, next to ICCR), Suite No. -

KRAKAUER-DISSERTATION-2014.Pdf (10.23Mb)

Copyright by Benjamin Samuel Krakauer 2014 The Dissertation Committee for Benjamin Samuel Krakauer Certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Negotiations of Modernity, Spirituality, and Bengali Identity in Contemporary Bāul-Fakir Music Committee: Stephen Slawek, Supervisor Charles Capwell Kaushik Ghosh Kathryn Hansen Robin Moore Sonia Seeman Negotiations of Modernity, Spirituality, and Bengali Identity in Contemporary Bāul-Fakir Music by Benjamin Samuel Krakauer, B.A.Music; M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin May 2014 Dedication This work is dedicated to all of the Bāul-Fakir musicians who were so kind, hospitable, and encouraging to me during my time in West Bengal. Without their friendship and generosity this work would not have been possible. জয় 巁쇁! Acknowledgements I am grateful to many friends, family members, and colleagues for their support, encouragement, and valuable input. Thanks to my parents, Henry and Sarah Krakauer for proofreading my chapter drafts, and for encouraging me to pursue my academic and artistic interests; to Laura Ogburn for her help and suggestions on innumerable proposals, abstracts, and drafts, and for cheering me up during difficult times; to Mark and Ilana Krakauer for being such supportive siblings; to Stephen Slawek for his valuable input and advice throughout my time at UT; to Kathryn Hansen -

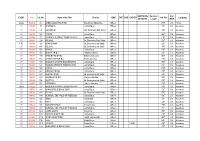

Convert JPG to PDF Online

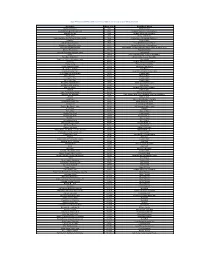

Withheld list SL # Roll No 1 12954 2 00220 3 00984 4 05666 5 00220 6 12954 7 00984 8 05666 9 21943 10 06495 11 04720 1 SL# ROLL Name Father Marks 1 00002 MRINALINI DEY PARIJAT KUSUM PATWARY 45 2 00007 MD. MOHIUL ISLAM LATE. MD. NURUL ISLAM 43 3 00008 MD. SALAM KHAN RUHUL AMIN KHAN 40 4 00014 SYED AZAZUL HAQUE SAYED FAZLE HAQUE 40 5 00016 ROMANCE BAIDYA MILAN KANTI BAIDYA 51 6 00018 DIPAYAN CHOWDHURY SUBODH CHOWDHURY 40 7 00019 MD. SHAHIDUL ISLAM MD. ABUL HASHEM 47 8 00021 MD. MASHUD-AL-KARIM SAHAB UDDIN 53 9 00023 MD. AZIZUL HOQUE ABDUL HAMID 45 10 00026 AHSANUL KARIM REZAUL KARIM 54 11 00038 MOHAMMAD ARFAT UDDIN MOHAMMAD RAMZU MIAH 65 12 00039 AYON BHATTACHARJEE AJIT BHATTACHARJEE 57 13 00051 MD. MARUF HOSSAIN MD. HEMAYET UDDIN 43 14 00061 HOSSAIN MUHAMMED ARAFAT MD. KHAIRUL ALAM 42 15 00064 MARJAHAN AKTER HARUN-OR-RASHED 45 16 00065 MD. KUDRAT-E-KHUDA MD. AKBOR ALI SARDER 55 17 00066 NURULLAH SIDDIKI BHUYAN MD. ULLAH BHUYAN 46 18 00069 ATIQUR RAHMAN OHIDUR RAHMAN 41 19 00070 MD. SHARIFUL ISLAM MD. ABDUR RAZZAQUE (LATE) 46 20 00072 MIZANUR RAHMAN JAHANGIR HOSSAIN 49 21 00074 MOHAMMAD ZIAUDDIN CHOWDHURY MOHAMMAD BELAL UDDIN CHOWDHURY 55 22 00078 PANNA KUMAR DEY SADHAN CHANDRA DEY 47 23 00082 WAYES QUADER FAZLUL QUDER 43 24 00084 MAHBUBUR RAHMAN MAZEDUR RAHMAN 40 25 00085 TANIA AKTER LATE. TAYEB ALI 51 26 00087 NARAYAN CHAKRABORTY BUPENDRA KUMER CHAKRABORTY 40 27 00088 MOHAMMAD MOSTUFA KAMAL SHAMSEER ALI 55 28 00090 MD. -

EVENT Year Lib. No. Name of the Film Director 35MM DCP BRD DVD/CD Sub-Title Language BETA/DVC Lenght B&W Gujrat Festival 553 ANDHA DIGANTHA (P

UMATIC/DG Duration/ Col./ EVENT Year Lib. No. Name of the Film Director 35MM DCP BRD DVD/CD Sub-Title Language BETA/DVC Lenght B&W Gujrat Festival 553 ANDHA DIGANTHA (P. B.) Man Mohan Mahapatra 06Reels HST Col. Oriya I. P. 1982-83 73 APAROOPA Jahnu Barua 07Reels EST Col. Assamese I. P. 1985-86 201 AGNISNAAN DR. Bhabendra Nath Saikia 09Reels EST Col. Assamese I. P. 1986-87 242 PAPORI Jahnu Barua 07Reels EST Col. Assamese I. P. 1987-88 252 HALODHIA CHORAYE BAODHAN KHAI Jahnu Barua 07Reels EST Col. Assamese I. P. 1988-89 294 KOLAHAL Dr. Bhabendra Nath Saikia 06Reels EST Col. Assamese F.O.I. 1985-86 429 AGANISNAAN Dr. Bhabendranath Saikia 09Reels EST Col. Assamese I. P. 1988-89 440 KOLAHAL Dr. Bhabendranath Saikia 06Reels SST Col. Assamese I. P. 1989-90 450 BANANI Jahnu Barua 06Reels EST Col. Assamese I. P. 1996-97 483 ADAJYA (P. B.) Satwana Bardoloi 05Reels EST Col. Assamese I. P. 1996-97 494 RAAG BIRAG (P. B.) Bidyut Chakravarty 06Reels EST Col. Assamese I. P. 1996-97 500 HASTIR KANYA(P. B.) Prabin Hazarika 03Reels EST Col. Assamese I. P. 1987-88 509 HALODHIA CHORYE BAODHAN KHAI Jahnu Barua 07Reels EST Col. Assamese I. P. 1987-88 522 HALODIA CHORAYE BAODHAN KHAI Jahnu Barua 07Reels FST Col. Assamese I. P. 1990-91 574 BANANI Jahnu Barua 12Reels HST Col. Assamese I. P. 1991-92 660 FIRINGOTI (P. B.) Jahnu Barua 06Reels EST Col. Assamese I. P. 1992-93 692 SAROTHI (P. B.) Dr. Bhabendranath Saikia 05Reels EST Col. -

27/11/2013 Notes

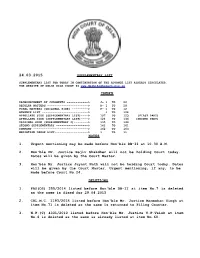

27/11/2013 SUPPLEMENTARY LIST SUPPLEMENTARY LIST FOR TODAY IN CONTINUATION OF THE ADVANCE LIST ALREADY CIRCULATED. THE WEBSITE OF DELHI HIGH COURT IS www.delhihighcourt.nic.in INDEX PRONOUNCEMENT OF JUDGMENTS ---------> J-1 TO J-2 REGULAR MATTERS --------------------> R-1 TO R-64 FINAL MATTERS (ORIGINAL SIDE) ------> F-1 TO F-8 ADVANCE LIST -----------------------> 1 TO 74 APPELLATE SIDE (SUPPLEMENTARY LIST)-> 75 TO 88 (FIRST PART) APPELLATE SIDE (SUPPLEMENTARY LIST)-> 89 TO 94 (SECOND PART) COMPANY ----------------------------> 95 TO 96 ORIGINAL SIDE (SUPPLEMENTARY I)-----> 97 TO 104 SECOND SUPPLEMENTARY ---------------> 105 TO 119 NOTES 1. Hon'ble Ms. Justice Veena Birbal will not be holding Court from 25th November 2013 to 9th December, 2013. Dates will be given by the Court Master. During the period of absence,fresh Criminal Leave Petitions & Criminal Revision Petitions will be allocated to Hon'ble Mr. Justice G.S.Sistani in place of Hon'ble Ms. Justice Veena Birbal. Regular Matters List is not being published. CIRCULAR VIDE NOTICE NO.909/COMP./DHC DATED. 23.10.2013, LAWYERS AND LITIGANTS WERE INFORMED THAT THIS COURT WILL START E-FILING IN COMPANY AND TAX JURISDICTIONS FROM 25TH OCTOBER, 2013 BUT IT HAS BEEN NOTICED THAT LAWYERS/ LITIGANTS ARE NOT AVAILING THIS FACILITY. IT IS NOW BROUGHT TO THE NOTICE OF THE LITIGANTS/ADVOCATES THAT W.E.F. 11TH NOVEMBER, 2013 E-FILING IN COMPANY AND TAX MATTERS IS MANDATORY AND REGISTRY WILL NOT ACCEPT FILING THROUGH ANY OTHER MODE. FOR THE PURPOSES OF E-FILING IN THE SAID JURISDICTIONS, A LAWYER OR A LITIGANT IN PERSON, AS THE CASE MAY BE, WILL NEED TO PURCHASE A DIGITAL SIGNATURE. -

NOTES 1. Urgent Mentioning May Be Made Before Hon'ble DB-II at 10.30

24.03.2015 SUPPLEMENTARY LIST SUPPLEMENTARY LIST FOR TODAY IN CONTINUATION OF THE ADVANCE LIST ALREADY CIRCULATED. THE WEBSITE OF DELHI HIGH COURT IS www.delhihighcourt.nic.in INDEX PRONOUNCEMENT OF JUDGMENTS ------------> J- 1 TO 02 REGULAR MATTERS -----------------------> R- 1 TO 58 FINAL MATTERS (ORIGINAL SIDE) ---------> F- 1 TO 12 ADVANCE LIST --------------------------> 1 TO 106 APPELLATE SIDE (SUPPLEMENTARY LIST)----> 107 TO 123 (FIRST PART) APPELLATE SIDE (SUPPLEMENTARY LIST)----> 124 TO 134 (SECOND PART) ORIGINAL SIDE (SUPPLEMENTARY I)--------> 135 TO 144 SECOND SUPPLEMENTARY ------------------> 145 TO 161 COMPANY -------------------------------> 162 TO 163 MEDIATION CAUSE LIST-------------------> 1 TO 11 NOTES 1. Urgent mentioning may be made before Hon'ble DB-II at 10.30 A.M. 2. Hon'ble Mr. Justice Rajiv Shakdher will not be holding Court today. Dates will be given by the Court Master. 3. Hon'ble Mr. Justice Jayant Nath will not be holding Court today. Dates will be given by the Court Master. Urgent mentioning, if any, to be made before Court No.24. DELETIONS 1. FAO(OS) 255/2014 listed before Hon'ble DB-II at item No.7 is deleted as the same is fixed for 29.04.2015 2. CRL.M.C. 1193/2015 listed before Hon'ble Mr. Justice Manmohan Singh at item No.71 is deleted as the same is returned to Filing Counter. 3. W.P.(C) 4331/2010 listed before Hon'ble Mr. Justice V.P.Vaish at item No.6 is deleted as the same is already listed at item No.60. Delhi High Court Legal Services Committee is holding the Pre-Lok Adalat sittings w.e.f. -

Let's Talk About Films – Again!

Follow Us: Today's Edition | Thursday , October 4 , 2012 | Search IN TODAY'S PAPER Front Page > Calcutta > Story Front Page Like 30 Tw eet 4 0 Nation Tw eet Calcutta Bengal Let’s talk about films – again! Opinion International In 1947, a group of cinephiles started a film society that Business revolutionised Bengali cinema and brought it into the forefront of world cinema. The group of cinephiles in Sports question? Satyajit Ray, Chidananda Dasgupta, Bansi Entertainment Chandragupta, Harisadhan Dasgupta…. The society Sudoku was the Calcutta Film Society (CFS). The first film Sudoku New BETA screened there was Sergei Eisenstein’s Battleship Crossword Potemkin. Jumble Regular screenings of world cinema gave access to the Gallery best of cinema across the globe. There were regular Horse Racing addas on films and eminent people delivered lectures at Press Releases the society, film-makers of the stature of Jean Renoir Travel and John Huston. By now it is part of folklore the influence that Renoir had on the young Ray and how WEEKLY FEATURES Pather Panchali was made a few years down the line. 7days Graphiti There was a bulletin that was published where the contributors were the likes of Knowhow Chidananda Dasgupta, Satyajit Ray and Harisadhan Dasgupta and those are some of Jobs the best pieces of film-writing to come out from Bengal. Ray’s Our Films, Their Films Careergraph was written in that period of his life. Salt Lake The Calcutta Film Society has dwindled ever since, more so in the last few decades. CITIES AND REGIONS Concomitantly, the culture of discussing and debating films, or a film culture as started Metro by the CFS, has faded into oblivion in the current Bengali film industry. -

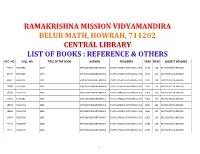

Ramakrishna Mission Vidyamandira Belur Math, Howrah, 711202 Central Library List of Books : Reference & Others Acc

RAMAKRISHNA MISSION VIDYAMANDIRA BELUR MATH, HOWRAH, 711202 CENTRAL LIBRARY LIST OF BOOKS : REFERENCE & OTHERS ACC. NO. CALL. NO. TITLE OF THE BOOK AUTHOR PUBLISHER YEAR PRICE SUBJECT HEADING 44638 R032/ENC 1978 ENYCOLPAEDIA BRITANNICA ENCYCLOPAEDIA BRITANNICA, ING 1978 150 ENCYCLOPEDIA-ENGLISH 44639 R032/ENC 1979 ENYCOLPAEDIA BRITANNICA ENCYCLOPAEDIA BRITANNICA, ING 1979 100 ENCYCLOPEDIA-ENGLISH 44641 R-032/BRI 1981 ENYCOLPAEDIA BRITANNICA ENCYCLOPEADIA BRITANNICA, INC 1981 100 ENCYCLOPEDIA-ENGLISH 15648 R-032/BRI 1982 ENYCOLPAEDIA BRITANNICA ENCYCLOPAEDIA BRITANNICA, ING 1982 100 ENCYCLOPEDIA-ENGLISH 15649 R-032/ENC 1983 ENYCOLPAEDIA BRITANNICA ENCYCLOPAEDIA BRITANNICA, ING 1983 100 ENCYCLOPEDIA-ENGLISH 17913 R032/ENC 1984 ENYCOLPAEDIA BRITANNICA ENCYCLOPAEDIA BRITANNICA, ING 1984 350 ENCYCLOPEDIA-ENGLISH 18648 R-032/ENC 1985 ENYCOLPAEDIA BRITANNICA ENCYCLOPAEDIA BRITANNICA, ING 1985 100 ENCYCLOPEDIA-ENGLISH 18786 R-032/ENC 1986 ENYCOLPAEDIA BRITANNICA ENCYCLOPAEDIA BRITANNICA, ING 1986 100 ENCYCLOPEDIA-ENGLISH 19693 R-032/ENC 1987 ENYCOLPAEDIA BRITANNICA ENCYCLOPEADIA BRITANNICA, INC 1987 100 ENCYCLOPEDIA-ENGLISH 21140 R-032/ENC 1988 ENYCOLPAEDIA BRITANNICA ENCYCLOPEADIA BRITANNICA, INC 1988 100 ENCYCLOPEDIA-ENGLISH 21141 R-032/ENC 1989 ENYCOLPAEDIA BRITANNICA ENCYCLOPEADIA BRITANNICA, INC 1989 100 ENCYCLOPEDIA-ENGLISH 1 ACC. NO. CALL. NO. TITLE OF THE BOOK AUTHOR PUBLISHER YEAR PRICE SUBJECT HEADING 21426 R-032/ENC 1990 ENYCOLPAEDIA BRITANNICA ENCYCLOPAEDIA BRITANNICA, ING 1990 150 ENCYCLOPEDIA-ENGLISH 21797 R-032/ENC 1991 ENYCOLPAEDIA -

Westminsterresearch the Digital Turn in Indian Film Sound

WestminsterResearch http://www.westminster.ac.uk/westminsterresearch The Digital Turn in Indian Film Sound: Ontologies and Aesthetics Bhattacharya, I. This is an electronic version of a PhD thesis awarded by the University of Westminster. © Mr Indranil Bhattacharya, 2019. The WestminsterResearch online digital archive at the University of Westminster aims to make the research output of the University available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the authors and/or copyright owners. Whilst further distribution of specific materials from within this archive is forbidden, you may freely distribute the URL of WestminsterResearch: ((http://westminsterresearch.wmin.ac.uk/). In case of abuse or copyright appearing without permission e-mail [email protected] THE DIGITAL TURN IN INDIAN FILM SOUND: ONTOLOGIES AND AESTHETICS Indranil Bhattacharya A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the University of Westminster for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy March 2019 ii Abstract My project maps film sound practices in India against the backdrop of the digital turn. It is a critical-historical account of the transitional era, roughly from 1998 to 2018, and examines practices and decisions taken ‘on the ground’ by film sound recordists, editors, designers and mixers. My work explores the histories and genealogies of the transition by analysing the individual, as well as collective, aesthetic concerns of film workers migrating from the celluloid to the digital age. My inquiry aimed to explore linkages between the digital turn and shifts in production practices, notably sound recording, sound design and sound mixing. The study probes the various ways in which these shifts shaped the aesthetics, styles, genre conventions, and norms of image-sound relationships in Indian cinema in comparison with similar practices from Euro-American film industries. -

Longs Métrages

1 MISSION CINÉMA PARIS FILM ChAque ANNÉe PARIS SOutIeNt et ACCOMPAgNe… LA PRODuCtION De COuRtS MÉtRAgeS 950 tOuRNAgeS LeS SALLeS ARt et eSSAI et INDÉPeNDANteS LeS FeStIVALS et ÉVÉNeMeNtS Le FORuM DeS IMAgeS L’ÉDuCAtION Au CINÉMA © Sophie Robichon Mairie de Paris Paris de Mairie Robichon Sophie © Tournage de Jhoom Barabar Jhoom de Shaad Ali sur le parvis du Trocadéro, Paris. MiSSion CinEMA - PAriS FilM oFFiCE 4, rue François Miron - 75004 Paris phone : +33 1 44 54 19 60 / www.parisfilm.fr 2 MP01 PUB MC FESTIVAL CATALOGUE INDIA_22x29,7_10_2013.indd 1 08/10/13 17:40 promouvoir les échangesDialoguer entre laDécouvrir France et l’inde To know To exchange Découvrir la société indienne Créer des synergies Reveal talentsTalent Boldness révéler des œuvresAccompagner les artistes Echanger s’interroger s’étonner s’émerveillerSoutenir aimer questionner dialoguer s’inspirer Partager des valeurs To support the franco indian exchanges Extravagant India ! Festival International du Film Indien - Paris LONGS MÉTRAGES (COMPETITION) FEATURE FILMS (COMPETITION) CLASSIQUES DOCUMENTAIRES (COMPETITION) CLASSICS DOCUMENTARIES (COMPETITION) COURTS MÉTRAGES EVÉNEMENTS PROGRAMME SHORT FILMS EQUIPE EVENTS / MEETINGS PROGRAM TEAM Musicals - Films fantastiques - Adventure films - Science fiction - Dramas - Thrillers - Fiction - Animation - Documentaires - Documentaries - Expéri- mental - Action films - Musicals - Films fantastiques - Biopics - Comédies - Films d’horreur - Adventure films - Science fiction - Dramas - Thrillers - Fiction - Animation - Documentaires- Documentaries -

SONG CODE and Send to 4000 to Set a Song As Your Welcome Tune

Type WT<space>SONG CODE and send to 4000 to set a song as your Welcome Tune Song Name Song Code Artist/Movie/Album Aaj Apchaa Raate 5631 Anindya N Upal Ami Pathbhola Ek Pathik Esechhi 5633 Hemanta Mukherjee N Asha Bhosle Andhakarer Pare 5634 Somlata Acharyya Chowdhury Ashaa Jaoa 5635 Boney Chakravarty Auld Lang Syne And Purano Sei Diner Katha 5636 Shano Banerji N Subhajit Mukherjee Badrakto 5637 Rupam Islam Bak Bak Bakam Bakam 5638 Priya Bhattacharya N Chorus Bhalobese Diganta Diyechho 5639 Hemanta Mukherjee N Asha Bhosle Bhootader Bechitranusthan 56310 Dola Ganguli Parama Banerjee Shano Banerji N Aneek Dutta Bhooter Bhobishyot 56312 Rupankar Bagchi Bhooter Bhobishyot karaoke Track 56311 Instrumental Brishti 56313 Anjan Dutt N Somlata Acharyya Chowdhury Bum Bum Chika Bum 56315 Shamik Sinha n sumit Samaddar Bum Bum Chika Bum karaoke Track 56314 Instrumental Chalo Jai 56316 Somlata Acharyya Chowdhury Chena Chena 56317 Zubeen Garg N Anindita Chena Shona Prithibita 56318 Nachiketa Chakraborty Deep Jwele Oi Tara 56319 Asha Bhosle Dekhlam Dekhar Par 56320 Javed Ali N Anwesha Dutta Gupta Ei To Aami Club Kolkata Mix 56321 Rupam Islam Ei To Aami One 56322 Rupam Islam Ei To Aami Three 56323 Rupam Islam Ei To Aami Two 56324 Rupam Islam Ek Jhatkay Baba Ma Raji 56325 Shaan n mahalakshmi Iyer Ekali Biral Niral Shayane 56326 Asha Bhosle Ekla Anek Door 56327 Somlata Acharyya Chowdhury Gaanola 56328 Kabir Suman Hate Tomar Kaita Rekha 56329 Boney Chakravarty Jagorane Jay Bibhabori 56330 Kabir Suman Anjan Dutt N Somlata Acharyya Chowdhury Jatiswar 56361