Download Paper

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

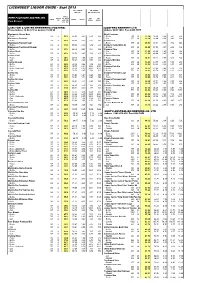

Final Liquor Guide Update Beer Aug 2013

UPDATE TO THE LICENSEES' LIQUOR GUIDE - Sept 2013 OFF PREMISE ON PREMISE INCL. GST BOTTLE INCL. GST W/SALE BEER PACKAGED AUSTRALIAN NO. PER INCL. EXCISE LOW HIGH SIZE ML CARTON BOTTLE from Brewers CTN. & BOT. DEP. MARGIN MARGIN EXCL. GST CARLTON & UNITED BREWERIES (FOSTERS) COOPERS BREWERY LTD Phone Orders: 13 23 37 Fax Orders: 13 22 82 Orders: 8440 1844 Fax: 8440 1999 Bluetongue Ginger Beer Birell Premium - Bottle 330 24 53.14 68.56 4.03 8.37 9.66 - Bottle 375 24 22.14 28.44 1.66 3.42 3.94 Bluetongue Premium - Can 375 24 22.14 28.44 1.66 3.42 3.94 - Bottle 330 24 54.10 69.80 4.11 8.53 9.83 Coopers 62 Bluetongue Premium Light - Bottle 355 24 46.53 60.01 3.53 7.32 8.44 - Bottle 330 24 37.29 48.05 2.82 5.84 6.73 Coopers Celebration Ale Bluetongue Traditional Pilsener - Bottles 355 24 44.50 57.38 3.37 6.99 8.06 - Bottle 330 24 53.14 68.56 4.03 8.37 9.66 Coopers Clear Carlton Black - Can 355 24 37.90 48.84 2.87 5.94 6.84 - Bottle 375 24 45.54 58.73 3.45 7.16 8.25 - Bottle 355 24 37.90 48.84 2.87 5.94 6.84 Carlton Cold Coopers Dark Ale - Bottle 375 24 38.14 49.15 2.89 5.97 6.89 - Bottle 375 24 38.97 50.22 2.95 6.11 7.04 - Can 375 30 44.28 57.04 2.68 5.54 6.39 Coopers Mild Ale Carlton Draught - Can 375 24 33.83 43.57 2.73 5.81 6.81 - Bottle 375 24 45.54 58.73 3.45 7.16 8.25 - Bottle 375 24 33.83 43.57 2.73 5.81 6.81 - Bottle 750 12 45.59 58.79 6.91 14.33 16.52 Coopers Pale Ale - Bottle (3x4 pack) 750 12 45.59 58.79 6.91 14.33 16.52 - Bottle 375 24 39.32 50.68 2.98 6.16 7.11 - Can 375 24 45.54 58.73 3.45 7.16 8.25 - Bottle 750 12 38.63 49.78 -

Australian Beer (Full Strength) Price List

Australian Beer (Full Strength) Price List Description 6 Pack Case Price 28 Pale Ale Btl 330Ml$ 24.99 $ 78.99 4 Pines Brew Hefeweizen 330Ml$ 22.99 $ 71.99 4 Pines Brew Kolsch Btl 330Ml$ 22.99 $ 71.99 4 Pines Brew Stout Btl 330Ml$ 71.99 $ 71.99 Badlands Pale Ale 330Ml$ 19.99 $ 62.99 Barecove Radler 330Ml$ 16.99 $ 46.99 Barossa Vly Org Ale Btl 330Ml$ 16.99 $ 78.99 Beez Neez Honeywheat 24*345Ml$ 18.99 $ 64.99 Bluetongue Trad Pils 6*330Ml$ 17.99 $ 59.99 Boags Classic Blonde Btl 375Ml$ 14.99 $ 49.99 Boags Draught Btl 375Ml$ 15.99 $ 46.99 Boags Premium Lgr Btl 375Ml$ 18.99 $ 51.99 Bohemium Pilzner Btl 345Ml$ 18.99 $ 59.99 Carlton Cold Btl 375Ml$ 13.99 $ 39.99 Carlton Crown Lgr Btl 375Ml$ 17.99 $ 51.99 Carlton Draught Btl 375Ml$ 14.99 $ 44.99 Carlton Draught Btl 15Pk 375Ml N/A$ 27.99 Carlton Draught Btl 3Pk 750Ml N/A$ 48.99 Carlton Dry Btl 355Ml$ 13.99 $ 43.99 Carlton Fusion Lemon 355Ml$ 16.99 $ 49.99 Cascade Blonde Lager 375Ml$ 17.99 $ 54.99 Cascade Pale Ale 750Ml N/A$ 55.99 Cascade Pale Ale Original $ 17.99 $ 52.99 Cascade Prem Lager Btl 375Ml$ 18.99 $ 55.99 Coopers 62 Pilsner 24*355Ml$ 19.99 $ 60.99 Coopers Clear Dry Btl 355Ml$ 15.99 $ 49.99 Coopers Pale Ale Btl 375Ml$ 16.99 $ 52.99 Coopers Pale Ale Btl 12*750Ml N/A$ 56.99 Coopers Spk Ale Btl 375Ml$ 18.99 $ 57.99 Coopers Spk Ale Btl 750Ml N/A$ 61.99 Coopers Stout Btl 12*750Ml N/A$ 63.99 Coopers Stout Btl 24*375Ml$ 19.99 $ 62.99 Crown Reserve Lager 750Ml N/A$ 89.99 Fat Yak Pale Ale 330Ml$ 18.99 $ 64.99 Hahn Super Dry 700Ml N/A$ 51.99 Hahn Super Dry Btl 330Ml$ 15.99 $ 45.99 Hef German Wheat -

2020/11/28 現在 Page 1 パソコン画面から”Ctrl" と ”F” キーで検索が出来ます。

2020/11/28 現在 Page 1 パソコン画面から”Ctrl" と ”F” キーで検索が出来ます。 ABC EXTRA STOUT Australia FOSTER'S LIGHT ICE Barbar Australia FOSTER'S SPECIAL BITTER HEILEMAN'S BEER SPECIAL EXPORT Australia Gosser KNIGHT 池田栄治 Australia HAHN GOLD Marry X'mas 戸川 文 Australia HAHN ICE SKOL 松永宣男 Australia HAHN ICE BEER Albania KAON 外山直璋 Australia HAHN Premium Albania KORCA 外山直璋 Australia HAHN PREMIUM Light Argentina ANTARCTICA PILSEN Mick Australia HAHN Super Dry PREMIUM 石川京子 Argentina Barba Roja Morena 小池澄雄 Australia HARN Argentina Barba Roja Rubia 小池澄雄 Australia HARN Premium 栗坂溢實 Argentina Beagle FUEGIAN ALE Australia hi Liki LEMON MOLT Argentina Beagle FUEGIAN STOUT Australia J.Boag & Son BOAG'S XXX ALE 高橋美恵子 Argentina Beagle INDIA PALE ALE Australia J.Boag & Son CLASSIC BITTER 高橋美恵子 Argentina BIECKERT Australia MACKESON STOUT(BLACK) Argentina CAPE HORN PALE ALE Australia MALTS AND HOPS Argentina CAPE HORN PILSEN Australia MATSO'S SMOKEY BISHOP DARK LAGER 生 出村隆行 Argentina CAPE HORN STOUT Australia MAXX BLONDE Premium Lager 石川京子 Argentina CERVEZA GOURMET BEER USHUAIA Hain Light 小池澄雄 Australia MELBOURNE 川喜多孝之 Argentina CERVEZA GOURMET BEER USHUAIA Hain Smoke 小池澄雄 Australia MELBOURNE BITTER Argentina CERVEZA ISENBECK PREMUIUM ARGENTINA Australia OUTBACK BLACK OPAL 合阪幸三 Argentina CERVEZA PATAGONIA Amber Lager Australia OUTBACK CHILLI BEER 合阪幸三 Argentina IMPERIAL Australia OUTBACK COUNTRY BITTER 合阪幸三 Argentina QUILMES Australia OUTBACK PALE ALE 合阪幸三 Argentina Quilmes Bock Australia OUTBACK PILSNER 合阪幸三 Argentina QUILMES CERVEZA 合阪幸三 Australia PLATINUM BLOND Argentina -

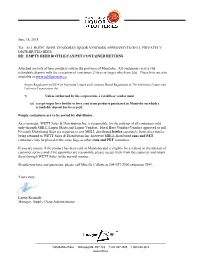

Empty Beer Bottle/Can/Pet Container Returns

June 18, 2018 TO: ALL HOTEL BEER VENDORS/LIQUOR VENDORS APPROVED TO SELL PRIVATELY DISTRIBUTED BEER RE: EMPTY BEER BOTTLE/CAN/PET CONTAINER RETURNS Attached are lists of beer products sold in the province of Manitoba. All containers carry a 10¢ refundable deposit with the exception of containers 2 litres or larger which are 20¢. These lists are also available at www.mbllpartners.ca. As per Regulation 68/2014 of Manitoba Liquor and Lotteries Board Regulation to The Manitoba Liquor and Lotteries Corporation Act: ‘1 Unless authorized by the corporation, a retail beer vendor must (a) accept empty beer bottles or beer cans from products purchased in Manitoba on which a refundable deposit has been paid; Empty containers are to be sorted by distributor. As a reminder, WETT Sales & Distribution Inc. is responsible for the pick-up of all containers sold only through MBLL Liquor Marts and Liquor Vendors. Hotel Beer Vendors/Vendors approved to sell Privately Distributed Beer are required to sort MBLL distributed bottles separately from other bottles being returned to WETT Sales & Distribution Inc, however MBLL distributed cans and PET containers may be placed in the same bags as other cans and PET containers. If you are unsure if the product has been sold in Manitoba and is eligible for a refund, in the interest of customer service and if the quantities are reasonable, please accept them from the customer and return them through WETT Sales in the normal manner. Should you have any questions, please call Mireille Collette at 204-957-2500 extension -

L Ig H T S T an D a R D $150.00 $25.00

PER BREW PER CARTON # GOANNA BREW IF YOU LIKE... ALC/VOL STYLE 50L = 24x345mL 6 Cartons Stubbies 81 United Bay Mild Carlton Mid 3.50% Lager 86 Eagle Light Eagle Blue 2.70% 79 Big Bird Draught Emu Draft 3.60% Mid Strength Australian 76 Forest Special Fosters Special 2.80% Lager 88 Premium Lite Hahn Ice Lite 3.00% Pale Lager (GF) Lighter Corona 3.50% Pale Lager T 92 King Lite (GF) Lighter Crown Lager 3.70% Lager H $150.00 $25.00 82 Billabong Bay Bitter Matilda Bay Bitter 3.30% Pale Ale IG L 91 Spider Lite Redback Lite 3.50% Kristalweizen 84 Golden WA Light Swan Gold 3.50% Lager 77 Easy Blue Tooheys Blue 2.70% Lager 87 Stones Corner Light West End Light 2.70% Lager 75 Four Men Lite XXXX Gold 3.50% Lager 170 Non-Alcoholic Ginger Beer Ginger Beer 0.00% Australian 78 Classic Pilsner Light (GF) Bud or Miller’s Light 4.00% Lager 28 United Cold Carlton Cold 4.80% Lager 12 Whitsunday Draught Carlton Draught 4.90% Lager 90 Devil Lite (GF) Cascade Light 4.00% Lager 18 Big Bird Bitter Emu Bitter 4.40% Ale D R 7 Forest Lager Fosters Lager 4.90% Lager A 8 Hodges Ice Hahn Ice 4.60% Lager D $150.00 $25.00 85 Columbia Lite Labatt Lite 4.40% Pale Lager AN 89 Ellas Lite Stella Light 4.00% Lager T S 3 Easy Red Tooheys Red 4.80% Lager 5 MCG Bitter VB 4.80% Lager 13 Stones Corner Lager West End Export 4.80% Lager 1 Four Man Bitter XXXX Bitter 4.70% Lager 132 Belgian Beer Belgian style beer 7.30% Belgian Ale 134 Wheat Bock Bock style 6.70% Bock 143 Boddies Ale Boddingstons Pub Ale 5.00% English Pale Ale 137 Devil Stout Cascade Stout 6.30% Stout 129 Expresso Stout Coee Stout style beer 5.90% Stout 139 Sparks Ale Coppers Sparkling Ale 5.50% Ale 124 Dort Export D.A.B. -

Bière : Les Quatre Multinationales Qui Se Cachent Derrière Des Centaines De Marques

Bière : les quatre multinationales qui se cachent derrière des centaines de marques Le Monde.fr | 08.10.2015 à 14h21 • Mis à jour le 08.10.2015 à 17h31 | Par Mathilde Damgé (/journaliste/mathilde- damge/) A l’image de Munich, capitale allemande de la bière, Paris a décidé d’organiser sa première Oktoberfest, qui commence jeudi 8 octobre. Une opération très « marketing » (avec un prix d’entrée à 35 euros), à l’image d’un marché très concentré en dépit des centaines de marques proposées dans les bars, restaurants et grandes surfaces aux quatre coins de la planète . Et la tendance à la concentration pourrait s’accélérer : le numéro deux mondial de la bière SABMiller a rejeté mercredi une nouvelle offre d’achat de plus de 90 milliards d’euros présentée par son rival, le numéro un AB InBev, visant à créer un mastodonte du secteur mariant la Stella Artois et la Pilsner Urquell. Lire aussi : SABMiller rejette l’offre à 92 milliards d’euros du géant de la bière AB InBev (/entreprises/article/2015/10/07/brasseurs-ab-inbev-releve-son-offre-d-achat-sur- sabmiller_4783951_1656994.html) Les quatre leaders mondiaux, AB InBev, suivi de SABMiller, de Heineken et de Carlsberg, brassent près de la moitié de la bière mondiale et exploitent près de 800 marques à eux seuls. Ci-dessous, les marques exploitées par le néerlandais Heineken (18,4 milliards d’euros de chiffre d’affaires en 2012), le belge Anheuser-Busch InBev (29 milliards d’euros de chiffre d’affaires en 2012), le britannique SABMiller (25,42 milliards d’euros de chiffre d’affaires en 2012) et le danois Carlsberg (9 milliards d’euros de chiffre d’affaires en 2012). -

Profile Beer Type ABV Similar to Description

Call today to place your order (08) 9343 5777 Profile Beer Type ABV Similar to Description FULL Australian Lager 5.00 Fosters Straw-Yellow Lager with bright white head FULL Long Neck Lager 4.90 Crown Lager Light coloured, full flavoured lager, a beer for all seasons. FULL W.A's Summer Ale 4.40 BRU Original A light coloured ale which is sweet on the palate FULL Four Kisses Bitter 4.90 XXXX Quality Queensland style beer FULL Rotterdam Dark Mild 4.90 Heineken Dark Dark with plenty of flavour, great with a roast FULL Demon's Bitter 5.00 Melbourne Bitter Crisp hoppy Lager, not just for the Vic's FULL Bass Strait Lager 5.00 Cascade A smooth Lager with a crisp finish, bite like a Tassie Tiger FULL Australian Red Lager 4.70 Toohey's Red Fresh hop flavour with Amber Malt FULL American Classic Pilsener 4.70 Budweiser Light colour & body, smooth as a Cadillac FULL Bavarian Weiss 4.50 BRU Original Has character of its own, wheat beer, refreshing all seasons FULL Mexican Wheat 5.00 Corona Pale light beer. Add a slice of lemon or lime FULL Greenwood Lager 5.00 Hahn Premium A pleasant bitter herbaceous brew, great with Asian food FULL Dutch Premium Pilsener 5.20 Heineken Smooth medium bodied beer with a refreshing aftertaste FULL Blue's Lager 5.00 Carlton Cold Fine light Lager, a perfect quencher after mowing the lawn FULL Western Bitter 5.00 Emu Bitter Pronounced bitterness & aroma, typical West Aussie Lager FULL Belgium Pilsener 5.00 Stella Atois A superb Lager. -

Thoughts on 1000 Beers

TThhoouugghhttss OOnn 11000000 BBeeeerrss DDaavviidd GGooooddyy Thoughts On 1000 Beers David Goody With thanks to: Friends, family, brewers, bar staff and most of all to Katherine Shaw Contents Introduction 3 Belgium 85 Britain 90 Order of Merit 5 Czech Republic 94 Denmark 97 Beer Styles 19 France 101 Pale Lager 20 Germany 104 Dark Lager 25 Iceland 109 Dark Ale 29 Netherlands 111 Stout 36 New Zealand 116 Pale Ale 41 Norway 121 Strong Ale 47 Sweden 124 Abbey/Belgian 53 Wheat Beer 59 Notable Breweries 127 Lambic 64 Cantillon 128 Other Beer 69 Guinness 131 Westvleteren 133 Beer Tourism 77 Australia 78 Full Beer List 137 Austria 83 Introduction This book began with a clear purpose. I was enjoying Friday night trips to Whitefriars Ale House in Coventry with their ever changing selection of guest ales. However I could never really remember which beers or breweries I’d enjoyed most a few months later. The nearby Inspire Café Bar provided a different challenge with its range of European beers that were often only differentiated by their number – was it the 6, 8 or 10 that I liked? So I started to make notes on the beers to improve my powers of selection. Now, over three years on, that simple list has grown into the book you hold. As well as straightforward likes and dislikes, the book contains what I have learnt about the many styles of beer and the history of brewing in countries across the world. It reflects the diverse beers that are being produced today and the differing attitudes to it. -

Distributors of Australian and New Zealand Food and Drinks

Distributors of Australian and New Zealand Food and Drinks 2013 Catalogue Australian Food and Drinks Page Savoury Biscuits . 2 Sweet Biscuits . 3 Chips . 4 Chocolate Bars Nestle . 5 Chocolate Bars Cadbury . 6 Chocolate Blocks . 7 Confectionary Sweets Allens . 8 Confectionary Sweets . 9 Alcohol Rum . 10 Alcohol Beer . 11-12 Other Drinks . 13 Bundaberg Ginger Beer . 14 Pantry . 15-16 New Zealand Food and Drinks Sweet Biscuits . 17 Chips . 18 Chocolate Bars . 19-20 Confectionary Bagged . 21 Confectionary K Bar . 22 Confectionary Wonka . 23-24 Alcohol . 25 Alcohol Monteiths . 26 Alcohol Beer . 27 Other Drinks – L&P . 28 Other Drinks – Fresh Up . 29 Pantry . 30 Pantry – Manuka Honey . 31 Order online at our website www.southernfoods.co.uk or telephone on 020 8367 4983 1 Header Image DESCRIPTION CARTON UNIT CARTON SKU PRODUCT QTY VAT PRICE PRICE EAN ORDER 4554 Arnotts Shapes - BBQ 200g box 24 9310072026268 Baked cracker coated in a delicious BBQ 9310072026268 flavouring. 5089 Arnotts Shapes - Cheese & Bacon 200g box 24 9310072026275 Baked cracker coated in a delicious Cheese & 9310072026275 Bacon flavouring. 4555 Arnotts Shapes - Pizza 200g box 24 9310072026305 Baked cracker coated in a delicious Pizza 9310072026305 flavouring. 5360 Arnotts Shapes - Chicken Crimpy 200g 24 9310072026312 Baked cracker coated in a delicious Chicken 9310072026312 flavouring. 8816 Sakata Original Rice Crackers - BBQ 100g 16 9319636000126 Arguably the most popular rice cracker in 9319636000126 Australia, generously coated in a BBQ seasoning. 8817 Sakata Original Rice Crackers - Plain 100g 16 9319636000140 Arguably the most popular rice cracker in 9319636000140 Australia, seasoned with a touch of salt. 2 Order online at our website www.southernfoods.co.uk or telephone on 020 8367 4983 Header Image DESCRIPTION CARTON UNIT CARTON SKU PRODUCT QTY VAT PRICE PRICE EAN ORDER 4882 Arnotts Tim Tams - Original 200g 24 • 19310072023608 The original Tim Tam, 2 layers of chocolate 19310072023608 biscuit, with a chocolate cream filling coated in a milk chocolate. -

Západočeská Univerzita V Plzni Fakulta

ZÁPADOČESKÁ UNIVERZITA V PLZNI FAKULTA EKONOMICKÁ Bakalá řská práce Efektivní nákup podniku Effective purchase Petr Št ěpán Cheb 2013 - 1 - Čestné prohlášení Prohlašuji, že jsem bakalá řskou práci na téma „Efektivní nákup podniku“ vypracoval samostatn ě pod odborným dohledem vedoucího bakalá řské práce za použití pramen ů uvedených v přiložené bibliografii. V Chebu, dne …………………………….. podpis autora - 3 - Pod ěkování Touto cestou bych rád pod ěkoval vedoucímu práce panu Dr. Ing. Ji římu Hofmanovi za odborné vedení, poskytnutí cenných rad a komentá řů p ři zpracování mé bakalá řské práce. Dále bych rád pod ěkoval zam ěstnanc ům spole čnosti Plze ňský Prazdroj, a.s. za umožn ění zpracování bakalá řské práce. - 4 - Obsah Úvod ............................................................................................................................ - 7 - 1 Charakteristika podniku Plze ňský Prazdroj, a.s............................................. - 8 - 1.1 Historie podniku od založení do sou časnosti .................................................... - 8 - 1.2 Sou časnost podniku Plze ňský Prazdroj, a.s. ................................................... - 10 - 1.3 Portfolio produkt ů ........................................................................................... - 11 - 1.4 Export .............................................................................................................. - 13 - 1.5 Produkce piva v letech 2007-2012 .................................................................. - 14 - 1.6 Zam ěstnanci ................................................................................................... -

Blue Moon Wine & Beer List Cider – Strong Bow, Sweet, Dry Or Original

Blue Moon wine & Beer List Cider – Strong bow, Sweet, Dry or Original $5.90 Super Premium Full Strength Beez Neez “Honey” Wheat Beer - 4.7%Alc Victoria $6.90 James Boags Premium Lager - 5%Alc Tasmania $6.50 Crown Lager - 4.9%Alc Victoria $6.50 Cascade Premium Lager - 5%Alc Tasmania $6.50 Hahn Premium Lager – 5%Alc NSW $6.50 Blue Tongue Premium Lager (Lizard Beer ) - 4.9%Alc NSW $6.90 Fat Yak Pale Ale - 4.7%Alc Victoria $6.90 Williams Organic Pale Ale - 4.5%Alc NSW $7.90 Wahoo Premium Ale “Reef Fish Beer” - 4.6%Alc WA $7.90 Mildura Desert “Gecko” Lager - 4.5%Alc Victoria $7.50 Little Creatures Pale Ale - 5.2%Alc WA $7.50 Far North Queensland Lager - 4.4%Alc Cairns Qld $7.50 Red Angus Pilsner - 4.8%Alc “Pure grain fed beer ” NSW $6.90 RedBack Wheat Beer - 4.7%Alc Victoria $7.50 Blue Sky Pilsner - 4.5%Alc “ Craft Beer ” Cairns Queensland $7.50 Super Premium Light Hahn Premium Lite - 2.6%Alc ( No Ads or Pres ) NSW $5.50 James Boags Premium Light - 2.9%Alc Tasmania $5.50 Cascade Premium Light - 2.6%Alc Tasmania $5.50 Premium Midstrength Crown Gold Premium - 3.5%Alc Victoria $5.50 XXXX Gold Lager low carb - 3.5%Alc Qld $5.00 Carlton Mid-Strength - 3.5%Alc Victoria $5.00 Cairns Gold Lager - 3.3%Alc Cairns Qld $7.00 Premium Light Fosters Lite Ice - 2.3%Alc Victoria $5.00 XXXX Lite Lager - 2.3%Alc Qld $5.00 Premium Full Strength Carlton Cold Filtered - 4%Alc Victoria $5.00 Carlton Draught - 4.6%Alc Victoria $5.00 Carlton Black Dark Ale - 4.4%Alc Victoria $5.50 Coopers Pale Ale (No Ads or Pres ) - 4.5%Alc S.A $5.50 Coopers Sparkling Ale (No Ads -

Light Range Full Flavour

LIGHT RANGE FULL FLAVOUR BREW Alc% 20 Australian CP 2.7 Fosters Special Light 18 Bouvard Nugget 3.5 Swan Gold 6 Cow Girl 3.2 Coors, Light Golden Mid Strength 72 Channel Light Bitter 3.5 Matilda Bay 91 Light Lygon 3.5 Carlton Mid Strength 95 PGL Light 3.5 Hahn Premium Light 62 Pilsner Light 3.5 Original American, Smooth As Silk Pilsner 71 WA Drought 3.5 Emu Draught 21 Worst End Bitter 2.7 West End Bitter 4 Straws 3.5 Stroh's Golden, Light Bodied American Lager FULL STRENGTH STANDARD RANGE 2 Classic American Pils 4.0 Budweiser Light, Fresh Aromatic Hops 73 Australian Amber Bitter 4.2 Emu Bitter 12 Australian Export 4.2 Fosters 28 Canadian Cow 4.2 Moosehead, Rich Lager With Delicate Hops 29 Canadian Pilsner 4.1 Labbats Blue, Light Malt Flavoured Pilsner 8 CCCCPPPP 4.1 XXXX, Classic Queenslander 3 Cowboy Lager 4.0 Coors, Golden Light Malt Dry Lager Style 110 Mexi Max 4.0 Corona Pale Light Beer. Easy Drinking 51 Mexican Crown 3.6 Corona Pale Light Beer. Easy Drinking 5 Milwaukee Lager 4.0 Miller Draught, Pale Light Flavoured Beer 74 Ossie Ostrich Lager 4.2 Emu Export A True West Aussie Styled Beer 94 PGL Lager 4.0 Hahn Premium, Light Coloured Full Bodied Beer 68 Tokyo Gold 4.1 Kirin, Mellow Light Coloured Japanese Lager 16 Dusty 3.7 3.7 Hahn super dry 3.5, Light bodied low hopped 15 Van Diemans Premium 4.1 Cascade, Smooth Golden Premium Beer FULL STRENGTH STANDARD RANGE 10 Australian Dark Ale 4.4 Tooheys Old 9 Aust Summer Ale 4.7 Tooheys Red 106 Beckers Best 4.8 Becks, Refreshing With A Hint Of Bitterness 98 Bogus Beer 4.5 James Boag Crisp,