Wild and Distant: Revolt and Revolution in Rojava

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Blood-Soaked Olive: What Is the Situation in Afrin Today? by Anthony Avice Du Buisson - 06/10/2018 01:23

www.theregion.org A blood-soaked olive: what is the situation in Afrin today? by Anthony Avice Du Buisson - 06/10/2018 01:23 Afrin Canton in Syria’s northwest was once a haven for thousands of people fleeing the country’s civil war. Consisting of beautiful fields of olive trees scattered across the region from Rajo to Jindires, locals harvested the land and made a living on its rich soil. This changed when the region came under Turkish occupation this year. Operation Olive Branch: Under the governance of the Afrin Council – a part of the ‘Democratic Federation of Northern Syria’ (DFNS) – the region was relatively stable. The council’s members consisted of locally elected officials from a variety of backgrounds, such as Kurdish official Aldar Xelil who formerly co-headed the Movement for a Democratic Society (TEVDEM) – a political coalition of parties governing Northern Syria. Children studied in their mother tongue— Kurdish, Arabic, or Syriac— in a country where the Ba’athists once banned Kurdish education. The local Self-Defence Forces (HXP) worked in conjunction with the People’s Protection Units (YPG) to keep the area secure from existential threats such as Turkish Security forces (TSK) and Free Syrian Army (FSA) attacks. This arrangement continued until early 2018, when Turkey unleashed a full-scale military operation called ‘ Operation Olive Branch’ to oust TEVDEM from Afrin. The Turkish government views TEVDEM and its leading party, the Democratic Union Party (PYD), as an extension of the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) – listed as a terrorist organisation in Turkey. Under the pretext of defending its borders from terrorism, the Turkish government sent thousands of troops into Afrin with the assistance of forces from its allies in Idlib and its occupied Euphrates Shield territories. -

Interpreting the PKK's Signals in Europe

PERSPECTIVES ON TERRORISM Volume II, Issue 11 Interpreting the PKK’s Signals in Europe By Vera Eccarius-Kelly ince the Kurdish Worker’s Party (PKK) unexpectedly abducted three German hikers near Mt. Ararat in Turkey on 8 July 2008, and then released them on 20 July, intelligence sources in Europe have in- tensified their surveillance of PKK operatives among members of the particularly numerous Kurdish S Diaspora in Germany.[1] According to German newspaper reports, the PKK demanded that in ex- change for the release of the hikers “Berlin stop its hostile politics towards the Kurds and the PKK in Ger- many”.[2] While the exact purpose of the abduction requires further analysis, it is clear that it was the armed branch of the PKK, known as the People’s Defense Forces (HPG), that kidnapped the German hikers at their Mt. Ararat encampment at 10,500 feet in the evening hours—only to release them unharmed some two weeks later.[3] Questions Related to an Abduction Several questions preoccupy security analysts in relation to this abduction. How should this event be inter- preted in Europe, and particularly in Germany? What signals did the PKK send? And, most importantly, is the PKK entering a renewed phase of high intensity activism and terrorism in Europe? This essay aims to provide a brief analysis of the often confusing and contradictory messages sent by European Kurdish circles.[4] Despite convoluted interpretations of Kurdish demands that are linked to a lack of unity among the many Kurdish organizations in Europe, it is possible to disentangle the underlying messages. -

Two Routes to an Impasse: Understanding Turkey's

Two Routes to an Impasse: Understanding Turkey’s Kurdish Policy Ayşegül Aydin Cem Emrence turkey project policy paper Number 10 • December 2016 policy paper Number 10, December 2016 About CUSE The Center on the United States and Europe (CUSE) at Brookings fosters high-level U.S.-Europe- an dialogue on the changes in Europe and the global challenges that affect transatlantic relations. As an integral part of the Foreign Policy Studies Program, the Center offers independent research and recommendations for U.S. and European officials and policymakers, and it convenes seminars and public forums on policy-relevant issues. CUSE’s research program focuses on the transforma- tion of the European Union (EU); strategies for engaging the countries and regions beyond the frontiers of the EU including the Balkans, Caucasus, Russia, Turkey, and Ukraine; and broader European security issues such as the future of NATO and forging common strategies on energy security. The Center also houses specific programs on France, Germany, Italy, and Turkey. About the Turkey Project Given Turkey’s geopolitical, historical and cultural significance, and the high stakes posed by the foreign policy and domestic issues it faces, Brookings launched the Turkey Project in 2004 to foster informed public consideration, high‐level private debate, and policy recommendations focusing on developments in Turkey. In this context, Brookings has collaborated with the Turkish Industry and Business Association (TUSIAD) to institute a U.S.-Turkey Forum at Brookings. The Forum organizes events in the form of conferences, sem- inars and workshops to discuss topics of relevance to U.S.-Turkish and transatlantic relations. -

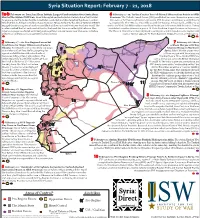

Syria SITREP Map 07

Syria Situation Report: February 7 - 21, 2018 1a-b February 10: Israel and Iran Initiate Largest Confrontation Over Syria Since 6 February 9 - 15: Turkey Creates Two Additional Observation Points in Idlib Start of the Syrian Civil War: Israel intercepted and destroyed an Iranian drone that violated Province: The Turkish Armed Forces (TSK) established two new observation points near its airspace over the Golan Heights. Israel later conducted airstrikes targeting the drone’s control the towns of Tal Tuqan and Surman in Eastern Idlib Province on February 9 and February vehicle at the T4 Airbase in Eastern Homs Province. Syrian Surface-to-Air Missile Systems (SAMS) 15, respectively. The TSK also reportedly scouted the Taftanaz Airbase north of Idlib City as engaged the returning aircraft and successfully shot down an Israeli F-16 over Northern Israel. The well as the Wadi Deif Military Base near Khan Sheikhoun in Southern Idlib Province. Turkey incident marked the first such combat loss for the Israeli Air Force since the 1982 Lebanon War. established a similar observation post at Al-Eis in Southern Aleppo Province on February 5. Israel in response conducted airstrikes targeting at least a dozen targets near Damascus including The Russian Armed Forces later deployed a contingent of military police to the regime-held at least four military positions operated by Iran in Syria. town of Hadher opposite Al-Eis in Southern Aleppo Province on February 14. 2 February 17 - 20: Pro-Regime Forces Set Qamishli 7 February 18: Ahrar Conditions for Major Offensive in Eastern a-Sham Merges with Key Ghouta: Pro-regime forces intensified a campaign 9 Islamist Group in Northern of airstrikes and artillery shelling targeting the 8 Syria: Salafi-Jihadist group Ahrar opposition-held Eastern Ghouta suburbs of Al-Hasakah a-Sham merged with Islamist group Damascus, killing at least 250 civilians. -

Protesting As a Terrorist Offense RIGHTS the Arbitrary Use of Terrorism Laws to Prosecute and Incarcerate Demonstrators in Turkey WATCH

Turkey HUMAN Protesting as a Terrorist Offense RIGHTS The Arbitrary Use of Terrorism Laws to Prosecute and Incarcerate Demonstrators in Turkey WATCH Protesting as a Terrorist Offense The Arbitrary Use of Terrorism Laws to Prosecute and Incarcerate Demonstrators in Turkey Copyright © 2010 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 1-56432-708-6 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch 350 Fifth Avenue, 34th floor New York, NY 10118-3299 USA Tel: +1 212 290 4700, Fax: +1 212 736 1300 [email protected] Poststraße 4-5 10178 Berlin, Germany Tel: +49 30 2593 06-10, Fax: +49 30 2593 0629 [email protected] Avenue des Gaulois, 7 1040 Brussels, Belgium Tel: + 32 (2) 732 2009, Fax: + 32 (2) 732 0471 [email protected] 64-66 Rue de Lausanne 1202 Geneva, Switzerland Tel: +41 22 738 0481, Fax: +41 22 738 1791 [email protected] 2-12 Pentonville Road, 2nd Floor London N1 9HF, UK Tel: +44 20 7713 1995, Fax: +44 20 7713 1800 [email protected] 27 Rue de Lisbonne 75008 Paris, France Tel: +33 (1)43 59 55 35, Fax: +33 (1) 43 59 55 22 [email protected] 1630 Connecticut Avenue, N.W., Suite 500 Washington, DC 20009 USA Tel: +1 202 612 4321, Fax: +1 202 612 4333 [email protected] Web Site Address: http://www.hrw.org November 2010 1-56432-708-6 Protesting as a Terrorist Offense The Arbitrary Use of Terrorism Laws to Prosecute and Incarcerate Demonstrators in Turkey I. Summary ......................................................................................................................... 1 Key Recommendations ..........................................................................................................6 Methodology ........................................................................................................................ -

University of Peloponnese Kurdish

University of Peloponnese Faculty of Social and Political Sciences Department of Political Studies and International Relations Master Program in «Mediterranean Studies» Kurdish women fighters of Rojava: The rugged pathway to bring liberation from mountains to women’s houses1. Zagoritou Aikaterini Corinth, January 2019 1 Reference in the institution of Rojava, Mala Jin (Women’s Houses) which are viewed as one of the most significant institutions in favour of women’s rights in local level. Πανεπιστήμιο Πελοποννήσου Σχολή Κοινωνικών και Πολιτικών Επιστημών Τμήμα Πολιτικής Επιστήμης και Διεθνών Σχέσεων Πρόγραμμα Μεταπτυχιακών Σπουδών «Μεσογειακές Σπουδές» Κούρδισσες γυναίκες μαχήτριες της Ροζάβα: Το δύσβατο μονοπάτι για την απελευθέρωση από τα βουνά στα σπίτια των γυναικών. 2 Ζαγορίτου Αικατερίνη Κόρινθος, Ιανουάριος 2019 2 Αναφορά στο θεσμό της Ροζάβα, Mala Jin (Σπίτια των Γυναικών) τα οποία θεωρούνται σαν ένας από τους σημαντικότερους θεσμούς υπέρ των δικαιωμάτων των γυναικών, σε τοπικό επίπεδο. Dedication This dissertation is dedicated to my beloved brother, Christos, who left us too soon but he is always present to my thought and soul. Acknowledgments A number of people have supported me in the course of this dissertation, in various ways. First of all, I would like to express my sincere thanks to my supervisors, Vassiliki Lalagianni, professor and director of the Postgraduate Programme, Master of Arts (M.A.) in “Mediterranean Studies” at the University of Peloponnese and Marina Eleftheriadou, Professor at the aforementioned MA, for their assistance, useful instructions and comments. I also would like to express my deep gratitude to my family and my companion; especially to both my parents who have been all this time more than supportive. -

1 of 4 Weekly Conflict Summary February 1-7, 2018 During The

Weekly Conflict Summary February 1-7, 2018 During the reporting period, the Turkish-led Operation Olive Branch offensive continued its advance into Afrin, the northwestern canton controlled by the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF, a US-backed, Kurdish- led organization). Elsewhere, pro-government forces continued their advance against opposition forces and ISIS fighters in the northern Hama/southern Aleppo countryside, further securing their control in the area. Following a significant uptick in attacks on both the opposition-controlled Idleb and Eastern Ghouta pockets, the UN humanitarian coordinator, Panos Moumtzis, called for an immediate one-month cessation of hostilities for the delivery of humanitarian aid. Lastly, a new opposition “operation room” has been formed in Idleb, with the stated goal of coordinating attacks against government forces. Figure 1 - Areas of control in Syria by February 7, with arrows indicating fronts of advance during the reporting period 1 of 4 Weekly Conflict Summary – February 1-7, 2018 Operation Olive Branch Operation Olive Branch forces took new territory, connecting previously isolated territories west of Raju and north of Balbal. Turkey-backed Operation Euphrates Shield forces also advanced northwest of A’zaz to take a mountaintop and village from the SDF. No gains have yet been made towards Tal Refaat along the southeastern front. There have been reports of abuses by advancing Turkish-backed, opposition Free Syrian Army (FSA) forces, including footage of Operation Olive Branch forces apparently mutilating the body of a deceased YPJ fighter (an all-female Kurdish unit within the SDF). Hundreds of US-trained YPG/SDF fighters from eastern SDF cantons arrived in Afrin this week, traveling through government-held territory to reinforce the SDF fighters on fronts against Olive Branch units. -

The Hugo Valentin Centre

The Hugo Valentin Centre Master Thesis in Holocaust and Genocide Studies Syrian Kurds amid Violence Depictions of Mass Violence against Syrian Kurdistan in Kurdish Media, 2014–2019 Student: Abdulilah Ibrahim Term and year: Spring 2021 Credits: 45 Supervisor: Tomislav Dulić Word count: 28553 Table of Contents List of tables ...................................................................................................................................... 2 List of figures .................................................................................................................................... 2 Abstract............................................................................................................................................... 3 Acknowledgment ............................................................................................................................ 4 Introduction ...................................................................................................................................... 5 Aims and Research Questions ................................................................................................. 6 Structure of the thesis ................................................................................................................ 7 Research overview ...................................................................................................................... 7 Theory and method...................................................................................................................14 -

Women Rights in Rojava- English

Table of Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................................................... 2 1- Women’s Political Role in the Autonomous Administration Project in Rojava ...................................... 3 1.1 Women’s Role in the Autonomous Administration ....................................................................... 3 1.1.1 Committees for Women ......................................................................................................... 4 1.1.2 The Women’s Committee ....................................................................................................... 4 1.1.3 Women’s Associations - The “Kongreya Star” ........................................................................ 5 1.2 Women’s Representation in Political and Administrative Bodies: ................................................. 6 2. Empowering Women in the Military Field ........................................................................................... 11 2.1 The Representation of Women in the Army ................................................................................ 11 2.2 The People’s Protection Units (YPG) and Women’s Protection Units (YPJ) ................................. 12 2.2.1 The Women’s Protection Units- YPJ ..................................................................................... 12 2.2.2 The People’s Protection Units- YPG ..................................................................................... -

Protesting As a Terrorist Offense RIGHTS the Arbitrary Use of Terrorism Laws to Prosecute and Incarcerate Demonstrators in Turkey WATCH

Turkey HUMAN Protesting as a Terrorist Offense RIGHTS The Arbitrary Use of Terrorism Laws to Prosecute and Incarcerate Demonstrators in Turkey WATCH Protesting as a Terrorist Offense The Arbitrary Use of Terrorism Laws to Prosecute and Incarcerate Demonstrators in Turkey Copyright © 2010 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 1-56432-708-6 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch 350 Fifth Avenue, 34th floor New York, NY 10118-3299 USA Tel: +1 212 290 4700, Fax: +1 212 736 1300 [email protected] Poststraße 4-5 10178 Berlin, Germany Tel: +49 30 2593 06-10, Fax: +49 30 2593 0629 [email protected] Avenue des Gaulois, 7 1040 Brussels, Belgium Tel: + 32 (2) 732 2009, Fax: + 32 (2) 732 0471 [email protected] 64-66 Rue de Lausanne 1202 Geneva, Switzerland Tel: +41 22 738 0481, Fax: +41 22 738 1791 [email protected] 2-12 Pentonville Road, 2nd Floor London N1 9HF, UK Tel: +44 20 7713 1995, Fax: +44 20 7713 1800 [email protected] 27 Rue de Lisbonne 75008 Paris, France Tel: +33 (1)43 59 55 35, Fax: +33 (1) 43 59 55 22 [email protected] 1630 Connecticut Avenue, N.W., Suite 500 Washington, DC 20009 USA Tel: +1 202 612 4321, Fax: +1 202 612 4333 [email protected] Web Site Address: http://www.hrw.org November 2010 1-56432-708-6 Protesting as a Terrorist Offense The Arbitrary Use of Terrorism Laws to Prosecute and Incarcerate Demonstrators in Turkey I. Summary ......................................................................................................................... 1 Key Recommendations ..........................................................................................................6 Methodology ........................................................................................................................ -

The Forging of Kurdish Identity in Turkey

Ethnopolitics, 2018 Vol. 17, No. 2, 130–146, https://doi.org/10.1080/17449057.2017.1339425 Oppression, Solidarity, Resistance: The Forging of Kurdish Identity in Turkey WILLIAM GOURLAY School of Social Sciences, Monash University, Melbourne, Australia ABSTRACT This paper examines the intersection of oppression and Kurdish resistance to the state in Turkey and the impacts these have on the formation of ethnic identity amongst the Kurds of Diyarbakır. It examines how repressive state measures imposed upon the Kurds, ostensibly to crush the PKK, rallied Kurdish political sentiment such that resistance to state hegemony expanded to encompass a much broader ‘popular resistance’. Resistance by ‘everyday’ Kurds to what they perceive as hegemonic projects, whether instigated by Kemalists or the AKP, continues to forge internal cohesion and highlight their differences from the majority Turks. In this way, resistance becomes a central pillar of Kurdish identity. Introduction One evening in October 2014, in the backstreets of the old city of Diyarbakır, I encoun- tered a group of Kurdish boys aged between 10 and 12 years. Fingers raised in the V- for-victory sign, with steadfast looks on their faces, they were chanting, ‘Bijıˆ serok Apo’. Translated from Kurdish, their chant means ‘Long live leader Apo’. They were brandishing the name of Abdullah O¨ calan, the leader of the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK), imprisoned near Istanbul since 1999. Local residents smiled and nodded as they passed. Although delivered in everyday surroundings, the boys’ gesture was undeniably political. Their posture was one of defiance. Why would small boys do such a thing? What sociopolitical circumstances would prompt boys to evoke the name of a jailed pol- itical leader in a nameless backstreet? How had a message of resistance been imbued in children so young? At the time of this encounter, the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS) was besieging the Kurdish city of Kobane 250 km away across the Syrian border. -

Information and Liaison Bulletin N°273

KURDINSTITUT E DE PARIS Information and liaison bulletin N°273 DECEMBER 2007 The publication of this Bulletin enjoys a subsidy from the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs (DGCID) aqnd the Fonds d’action et de soutien pour l’intégration et la lutte contre les discriminations (The Fund for action and support of integration and the struggle against discrimination) This bulletin is issued in French and English Price per issue : France: 6 € — Abroad : 7,5 € Annual subscribtion (12 issues) France : 60 € — Elsewhere : 75 € Monthly review Directeur de la publication : Mohamad HASSAN Numéro de la Commission Paritaire : 659 15 A.S. ISBN 0761 1285 INSTITUT KURDE, 106, rue La Fayette - 75010 PARIS Tel. : 01-48 24 64 64 - Fax : 01-48 24 64 66 www.fikp.org E-mail: [email protected] Contents : • THE PRESIDENT OF KURDISTAN, MASSUD BARZANI, REFUSES TO MEET CONDOLEEZA RICE IN IRAQ AS A PROTEST AGAINST THE TURKISH ARMY’S OPERATIONS IN IRAQI KURDISTAN • KIRKUK: THE KURDISTAN PARLIAMENT ACCEPTS UNO’S PROPOSAL TO POSTPONE THE REFERENDUM ON THE CITY’S STATUS FOR SIX MONTHS • BERLIN: THE GERMAN AUTHORITIES FREE, AHEAD OF TIME, THE ASSASSINS OF SADEGH SHARAFKANDI AND THREE OF HIS COMPANIONS OF THE KURDISTAN DEMOCRATIC PARTY OF IRAN • ANKARA: THE CONSTITUTIONAL COURT REJECTS THE PROVISIONAL MEASURES TO SUSPEND ALL PUBLIC ACTIVITY DEMANDED BY THE PROSECUTION AGAINST THE PRO-KURDISH DTP WHICH IS THREATENED WITH BANNING • THE LOWEST DEATH ROLL IN IRAQ SINCE FEBRUARY 2006: 568 IRAQIS KILLED IN DECEMBER • DAMASCUS: THE SYRIAN LEAGUE FOR THE DEFENCE OF HUMAN RIGHTS CONDEMNS