Jus Post Bellum

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project

The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project JOHN W. MCDONALD Interviewed by: Charles Stuart Kennedy Initial interview date: June 5, 1997 Copyright 2 3 ADST TABLE OF CONTENTS Background Born in Ko lenz, Germany of U.S. military parents Raised in military bases throughout U.S. University of Illinois Berlin, Germany - OMGUS - Intern Program 1,4.-1,50 1a2 Committee of Allied Control Council Morgenthau Plan Court system Environment Currency reform Berlin Document Center Transition to State Department Allied High Commission Bonn, Germany - Allied High Commission - Secretariat 1,50-1,52 The French Office of Special Representative for Europe General 6illiam Draper Paris, France - Office of the Special Representative for Europe - Staff Secretary 1,52-1,54 U.S. Regional Organization 7USRO8 Cohn and Schine McCarthyism State Department - Staff Secretariat - Glo al Briefing Officer 1,54-1,55 Her ert Hoover, 9r. 9ohn Foster Dulles International Cooperation Administration 1,55-1,5, E:ecutive Secretary to the Administration Glo al development Area recipients P1480 Point Four programs Anti-communism Africa e:perts African e:-colonies The French 1and Grant College Program Ankara, Turkey -CENTO - U.S. Economic Coordinator 1,5,-1,63 Cooperation programs National tensions Environment Shah of Iran AID program Micro2ave projects Country mem ers Cairo, Egypt - Economic Officer 1,63-1,66 Nasser AID program Soviets Environment Surveillance P1480 agreement As2an Dam Family planning United Ara ic Repu lic 7UAR8 National -

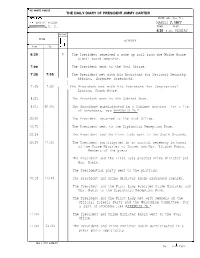

Ihe White House Iashington

HE WHITE HOUSE THE DAILY DIARY OF PRESIDE N T JIMMY CARTER LOCATION DATE (MO., Day, Yr.) IHE WHITE HOUSE MARCH 7, 1977 IASHINGTON, D. C. TIME DAY 6:30 a.m. MONDAY PHONE TIME = 0 E -u ACTIVITY 7 K 2II From To L p! 6:30 R The President received a wake up call from the White House signal board operator. 7:oo The President went to the Oval Office. 7:30 7:35 The President met with his Assistant for National Security Affairs,Zbigniew Brzezinski. 7:45 7:50 I I, The President met with his Assistant for Congressional Liaison, Frank Moore. 8:Ol The President went to the Cabinet Room. 8:Ol 10:05 The President participated in a Cabinet meeting For a list of attendees,see APPENDIX "A." 1O:05 The President returned to the Oval Office. 1O:25 The President went to the Diplomatic Reception Room. 1O:26 The President and the First Lady went to the South Grounds. 1O:26 1l:OO The President participated in an arrival ceremony in honor of the Prime Minister of Israel and Mrs. Yitzhak Rabin. Members of the press The President and the First Lady greeted Prime Minister and Mrs. Rabin. The Presidential party went to the platform. 10:35 10:45 The President and Prime Minister Rabin exchanged remarks. The President and the First Lady escorted Prime Minister and Mrs. Rabin to the Diplomatic Reception Room. The President and the First Lady met with members of the Official Israeli Party and the Welcoming Committee. For a list of attendees ,see APPENDIX& "B." 11:oo The President and Prime Minister Rabin went to the Oval Office. -

Theory of War and Peace: Theories and Cases COURSE TITLE 2

Ilia State University Faculty of Arts and Sciences MA Level Course Syllabus 1. Theory of War and Peace: Theories and Cases COURSE TITLE 2. Spring Term COURSE DURATION 3. 6.0 ECTS 4. DISTRIBUTION OF HOURS Contact Hours • Lectures – 14 hours • Seminars – 12 hours • Midterm Exam – 2 hours • Final Exam – 2 hours • Research Project Presentation – 2 hours Independent Work - 118 hours Total – 150 hours 5. Nino Pavlenishvili INSTRUCTOR Associate Professor, PhD Ilia State University Mobile: 555 17 19 03 E-mail: [email protected] 6. None PREREQUISITES 7. Interactive lectures, topic-specific seminars with INSTRUCTION METHODS deliberations, debates, and group discussions; and individual presentation of the analytical memos, and project presentation (research paper and PowerPoint slideshow) 8. Within the course the students are to be introduced to COURSE OBJECTIVES the vast bulge of the literature on the causes of war and condition of peace. We pay primary attention to the theory and empirical research in the political science and international relations. We study the leading 1 theories, key concepts, causal variables and the processes instigating war or leading to peace; investigate the circumstances under which the outcomes differ or are very much alike. The major focus of the course is o the theories of interstate war, though it is designed to undertake an overview of the literature on civil war, insurgency, terrorism, and various types of communal violence and conflict cycles. We also give considerable attention to the methodology (qualitative/quantitative; small-N/large-N, Case Study, etc.) utilized in the well- known works of the leading scholars of the field and methodological questions pertaining to epistemology and research design. -

Phd in Political Science Comprehensive Examination Guidebook

Department of Political Science __________________________________________________________ PhD in Political Science Comprehensive Examination Guidebook Contents Pages 2-3: Examination Overview and General Directions Pages 4-10: Reading Lists Page 4- Methodology Page 5- American Government Page 6- Comparative Politics Page 7- International Relations Page 9- Public Policy Page 11-13: Sample Questions for Written Examination Page 11- Methodology Page 12- American Government Page 12- Comparative Politics Page 12- International Relations Page 13- Public Policy EXAMINATION OVERVIEW AND GENERAL DIRECTIONS Doctoral students sit For the comprehensive examination at the conclusion of all required coursework, or during their last semester of coursework. Students will ideally take their exams during the fifth semester in the program, but no later than their sixth semester. Advanced Entry students are strongly encouraged to take their exams during their Fourth semester, but no later than their FiFth semester. The comprehensive examination is a written exam based on the literature and research in the relevant Field of study and on the student’s completed coursework in that field. Petitioning to Sit for the Examination Your First step is to petition to participate in the examination. Use the Department’s graduate petition form and include the following information: 1) general statement of intent to sit For a comprehensive examination, 2) proposed primary and secondary Fields areas (see below), and 3) a list or table listing all graduate courses completed along with the Faculty instructor For the course and the grade earned This petition should be completed early in the registration period For when the student plans to sit For the exam. -

Jus Post Bellum

The Unjustness of the Current Incantation of Jus Post Bellum by Dan G. Cox us post bellum was originally conceived as an extension of modern just war theory. Specifically, it was aimed at examining the justness and morality of actions during war, jus in bello, in relationship to negotiations for peace in the post-war setting. Under the initial conception of Jjus post bellum, considerations of distinction of enemies from civilians, for example, takes on a more pointed meaning, as one has to calculate how much collateral damage is appropriate given the longer-term end-goal of successful and beneficial peace negotiations. Unfortunately, jus post bellum has recently been expanded to mean that the victor in the war is now responsible for the long-term well-being of the people it has defeated. This has led to a concerted outcry for post-war nation-building, which neither leads necessarily to successful negotiations, nor ensures a better or lasting peace. In fact, current conceptions of jus post bellum remove national interest from the equation altogether, replacing all military endeavors with one monolithic national interest—liberal imperialism.1 Further, current incantations of jus post bellum obviate the possibility of a punitive strike or punitive expedition, even though this might be exactly what is needed in certain cases to create a better peace than existed prior to conflict. This article is an exploration of the current incantation of jus post bellum. The concept of an incantation was chosen purposively, as proponents of jus post bellum are engaging in a dogmatic approach to war termination oblivious to the complexities and realities of conflict and, in fact, in violation of just war theory itself. -

The Nobel Peace Prize

TITLE: Learning From Peace Makers OVERVIEW: Students examine The Dalai Lama as a Nobel Laureate and compare / contrast his contributions to the world with the contributions of other Nobel Laureates. SUBJECT AREA / GRADE LEVEL: Civics and Government 7 / 12 STATE CONTENT STANDARDS / BENCHMARKS: -Identify, research, and clarify an event, issue, problem or phenomenon of significance to society. -Gather, use, and evaluate researched information to support analysis and conclusions. OBJECTIVES: The student will demonstrate the ability to... -know and understand The Dalai Lama as an advocate for peace. -research and report the contributions of others who are recognized as advocates for peace, such as those attending the Peace Conference in Portland: Aldolfo Perez Esquivel, Robert Musil, William Schulz, Betty Williams, and Helen Caldicott. -compare and contrast the contributions of several Nobel Laureates with The Dalai Lama. MATERIALS: -Copies of biographical statements of The Dalai Lama. -List of Nobel Peace Prize winners. -Copy of The Dalai Lama's acceptance speech for the Nobel Peace Prize. -Bulletin board for display. PRESENTATION STEPS: 1) Students read one of the brief biographies of The Dalai Lama, including his Five Point Plan for Peace in Tibet, and his acceptance speech for receiving the Nobel Prize for Peace. 2) Follow with a class discussion regarding the biography and / or the text of the acceptance speech. 3) Distribute and examine the list of Nobel Peace Prize winners. 4) Individually, or in cooperative groups, select one of the Nobel Laureates (give special consideration to those coming to the Portland Peace Conference). Research and prepare to report to the class who the person was and why he / she / they won the Nobel Prize. -

From Just War to Just Intervention Susan J

New England Journal of Public Policy Volume 19 | Issue 1 Article 5 9-21-2003 From Just War to Just Intervention Susan J. Atwood University of Minnesota - Twin Cities Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.umb.edu/nejpp Part of the International Relations Commons, Military, War and Peace Commons, and the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Atwood, Susan J. (2003) "From Just War to Just Intervention," New England Journal of Public Policy: Vol. 19: Iss. 1, Article 5. Available at: http://scholarworks.umb.edu/nejpp/vol19/iss1/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks at UMass Boston. It has been accepted for inclusion in New England Journal of Public Policy by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at UMass Boston. For more information, please contact [email protected]. From Just War to Just Intervention Susan J. Atwood What is Just War? What is Just Intervention? This paper examines the evolution of the criteria for Just War from its origins in the early Christian church to the twenty-first century. The end of the Cold War era has expanded the discussion to include grounds for intervention. Indeed, in the 1990s, a number of multilat- eral interventions took place on humanitarian grounds. But the debate is ongoing about whether the criteria applied in the Just War theory — proper authority, just cause, and right intent — remain valid in an era of Just Intervention. The author examines as case studies some multilateral interven- tions and the lessons learned from them as we seek to develop the framework of international law to address the evolving theory and current practice of Just Intervention. -

Phoenix IV and Phoenix

AP/GT Phoenix III ~ SUMMER READING, 2018 Assignment: Read at least three books this summer, one for discussion as a class during the first week of school and at least two more of your own choosing, simply for pleasure. Book #1: Teacher Choice: The Signet Book of American Essays, Edited by M. Jerry Weiss and Helen S. Weiss ISBN-10: 0451530217 ISBN-13: 978-0451530219 Read Mark Twain’s “Advice to Youth” and at least three (3) other selections from this essay collection. You may read any three that you like EXCEPT “Letter from Birmingham Jail” by Martin Luther King, Jr. and “Civil Disobedience” by Henry David Thoreau which we will read together later in the school year. Be prepared to discuss Twain’s essay and your three chosen selections during the first week of school. Books #2 and #3: Student Choice: Read at least two books of your own choosing. they may be classic works or contemporary pieces one must be fiction, one must be non-fiction they may be from any genre (history, science fiction, memoir, mystery, religion, etc.) they must be written for an adult audience For suggestions, see the list of AP authors on the back of this sheet. You do not have to select authors from this list, but it is an excellent place to start. You may also refer to the “Looking for a Good Book?” tab on Ms. Hughes’ website, the bestsellers list of The New York Times, Dallas Morning News, or any other reputable source for suggestions. In addition, librarians, family, and friends can be excellent sources. -

How the Kremlin Weaponizes Information, Culture and Money by Peter Pomerantsev and Michael Weiss

The Menace of Unreality: How the Kremlin Weaponizes Information, Culture and Money by Peter Pomerantsev and Michael Weiss A Special Report presented by The Interpreter, a project of the Institute of Modern Russia imrussia.org interpretermag.com The Institute of Modern Russia (IMR) is a nonprofit, nonpartisan public policy organization—a think tank based in New York. IMR’s mission is to foster democratic and economic development in Russia through research, advocacy, public events, and grant-making. We are committed to strengthening respect for human rights, the rule of law, and civil society in Russia. Our goal is to promote a principles- based approach to US-Russia relations and Russia’s integration into the community of democracies. The Interpreter is a daily online journal dedicated primarily to translating media from the Russian press and blogosphere into English and reporting on events inside Russia and in countries directly impacted by Russia’s foreign policy. Conceived as a kind of “Inopressa in reverse,” The Interpreter aspires to dismantle the language barrier that separates journalists, Russia analysts, policymakers, diplomats and interested laymen in the English-speaking world from the debates, scandals, intrigues and political developments taking place in the Russian Federation. CONTENTS Introductions ...................................................................... 4 Executive Summary ........................................................... 6 Background ........................................................................ -

Cox, Abstract, the Injustice of the Current Incantation of Jus Post Bellum

The Injustice of the Current Incantation of Jus Post Bellum Dan G. Cox, Ph. D., School of Advanced Military Studies, US Army, [email protected] 9137583319 Abstract: Jus post bellum was originally conceived as an extension of modern just war theory. Specifically, it was aimed at examining the justness and morality of actions during war, jus in bello, in relationship to negotiations for peace in the post-war setting. Under the initial conception of jus post bellum, considerations of distinction of enemies from civilians, for example, takes on a more pointed meaning as one has to calculate how much collateral damage, even if allowed for in just in bello, is appropriate given the longer-term end-goal of successful and beneficial peace negotiations. Unfortunately, jus post bellum has been expanded to mean that the victor in the war is now responsible for the well-being of the people and/or nation it has defeated. This has led to a concerted cry for post-war nation-building which neither leads necessarily to successful negotiations nor ensures a better or lasting peace. In fact, current conceptions of jus post bellum remove national interest from the equation altogether replacing all military endeavors with one monolithic national interest; liberal imperialism1. Further, current incantations of jus post bellum obviate the possibility of a punitive strike or punitive expedition even though this might be exactly what is needed in certain cases to create a better peace than existed prior to conflict. This paper will explore the genesis and evolution of the jus post bellum concept. -

In a Rather Emotional State?' the Labour Party and British Intervention in Greece, 1944-5

ORE Open Research Exeter TITLE 'In a rather emotional state?' The Labour party and British intervention in Greece, 1944-5 AUTHORS Thorpe, Andrew JOURNAL The English Historical Review DEPOSITED IN ORE 12 February 2008 This version available at http://hdl.handle.net/10036/18097 COPYRIGHT AND REUSE Open Research Exeter makes this work available in accordance with publisher policies. A NOTE ON VERSIONS The version presented here may differ from the published version. If citing, you are advised to consult the published version for pagination, volume/issue and date of publication 1 ‘IN A RATHER EMOTIONAL STATE’? THE LABOUR PARTY AND BRITISH INTERVENTION IN GREECE, 1944-45* Professor Andrew Thorpe Department of History University of Exeter Exeter EX4 4RJ Tel: 01392-264396 Fax: 01392-263305 Email: [email protected] 2 ‘IN A RATHER EMOTIONAL STATE’? THE LABOUR PARTY AND BRITISH INTERVENTION IN GREECE, 1944-45 As the Second World War drew towards a close, the leader of the Labour party, Clement Attlee, was well aware of the meagre and mediocre nature of his party’s representation in the House of Lords. With the Labour leader in the Lords, Lord Addison, he hatched a plan whereby a number of worthy Labour veterans from the Commons would be elevated to the upper house in the 1945 New Years Honours List. The plan, however, was derailed at the last moment. On 19 December Attlee wrote to tell Addison that ‘it is wiser to wait a bit. We don’t want by-elections at the present time with our people in a rather emotional state on Greece – the Com[munist]s so active’. -

Liberal Toleration in Rawls's Law of Peoples Author(S): by Kok‐Chor Tan Source: Ethics, Vol

Liberal Toleration in Rawls's Law of Peoples Author(s): by Kok‐Chor Tan Source: Ethics, Vol. 108, No. 2 (January 1998), pp. 276-295 Published by: The University of Chicago Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1086/233805 . Accessed: 10/12/2013 22:34 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The University of Chicago Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Ethics. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 129.64.99.141 on Tue, 10 Dec 2013 22:34:35 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions Liberal Toleration in Rawls's Law of Peoples* Kok-Chor Tan How should a liberal state respond to nonliberal ones? Should it refrain from challenging their nonconformity with liberal principles? Or should it criticize and even challenge their nonliberal political institutions and practices? In ``The Law of Peoples,'' 1 John Rawls argues that while tyran- nical regimes, namely, states which are warlike and/or abusive of the ba- sic rights of their own citizens, do not fall within the limits of liberal tol- eration, nonliberal but peaceful and well-ordered states, what he refers to as ``well-ordered hierarchical societies'' (WHSs), meet the conditions for liberal toleration.