REFLECTIONS PLANTATIONOCENE On

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CRITICAL THEORY INSTITUTE University of California, Irvine CTI

CRITICAL THEORY INSTITUTE University of California, Irvine CTI 2011 Wellek Library Lecture Series Donna Haraway Professor Emerita, History of Consciousness, University of California, Santa Cruz Playing Cat’s Cradle with Companion Species Monday, May 2nd, 5-7pm Tuesday, May 3rd, 5-7pm Thursday, May 5th, 5-7pm Humanities Gateway, 1030 Contact Information: Critical Theory Institute University of California, Irvine 433 Krieger Hall Irvine, CA 92697-5525 Phone (949) 824-5583 Fax (949) 824-2767 Director: Kavita Philip Admin. Coordinator: Lisa Clark [email protected] www.humanities.uci.edu/critical For information concerning accommodations for disabilities, please contact Lisa Clark at 949-824-5583 Donna Haraway: A Bibliography for the Occasion of the 31st Wellek Library Lectures Compiled by John Novak, UCI Research Librarian An electronic version of this and previous Wellek Library Lecture bibliographies with working electronic links will be maintained at this Web site: http://www.lib.uci.edu/about/publications/wellek/wellek-series.html Direct links to electronic materials may be accessed on-campus. Off-campus access is for the UCI community via the VPN. For more information, visit the following Web site: http://www.lib.uci.edu/how/connect-from-off-campus.html Table of Contents for Bibliography Works by Haraway ..................................................... 1 Haraway Interviews and Biographies ....................... 16 Selected Works About or Utilizing Haraway ............. 18 Works by Haraway 1975 "The Transformation of the Left in Science: Radical Associations in Britain in the 30s and the U.S.A. in the 60s." Soundings 58 4 (1975): 441-62. Print. Call Number: Langson Bound Periodicals BV 1460 C6 1976 Crystals, Fabrics, and Fields: Metaphors of Organicism in Twentieth-Century Developmental Biology. -

UC Santa Cruz Other Recent Work

UC Santa Cruz Other Recent Work Title "It Became My Case Study": Professor Michael Cowan's Four Decades at UC Santa Cruz Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/3j5438d7 Authors Cowan, Michael Reti, Irene Publication Date 2013-01-11 Supplemental Material https://escholarship.org/uc/item/3j5438d7#supplemental eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California University of California, Santa Cruz University Library “It Became My Case Study” Professor Michael Cowan’s Four Decades at UC Santa Cruz Interviewed and Edited by Irene Reti Santa Cruz 2013 This manuscript is covered by copyright agreement between Michael Cowan and the Regents of the University of California dated December 3, 2012. Under “fair use” standards, excerpts of up to six hundred words (per interview) may be quoted without the Regional History Project’s permission as long as the materials are properly cited. Quotations of more than six hundred words require the written permission of the University Librarian and a proper citation and may also require a fee. Under certain circumstances, not-for-profit users may be granted a waiver of the fee. To contact the Regional History Project: [email protected] or Regional History Project McHenry Library, UC Santa Cruz 1156 High Street Santa Cruz, CA 95064 Phone: 831-459-2847 Table of Contents Introduction vii Early Life 12 Yale University 23 Senior Thesis on the Boy Scouts of America 34 Graduate Work in American Studies at Yale 37 Teaching at Yale University 43 Coming to the University of California, -

The Mushroom at the End of the World : on the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins / Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing

Copyright © 2015 by Princeton University Press Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540 In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, 6 Oxford Street, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TW press.princeton.edu Jacket art: Homage to Minakata © Naoko Hiromoto All Rights Reserved Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Tsing, Anna Lowenhaupt. The mushroom at the end of the world : on the possibility of life in capitalist ruins / Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-691-16275-1 (hardcover : alk. paper) 1. Human ecology. 2. Economic development—Environmental aspects. 3. Environmental degradation. I. Title. GF21.T76 2015 330.1—dc23 2014037624 British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available This book has been composed in Sabon Next LT Pro and Syntax Printed on acid-free paper. ∞ Printed in the United States of America 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Contents Enabling Entanglements vii PROLOGUE. AUTUMN AROMA I PART I What’s Left? II 1 | Arts of Noticing 17 2 | Contamination as Collaboration 27 3 | Some Problems with Scale 37 INTERLUDE. SMELLING 45 PART II After Progress: Salvage Accumulation 55 4 | Working the Edge 61 FREEDOM … 5 | Open Ticket, Oregon 73 6 | War Stories 85 7 | What Happened to the State? Two Kinds of Asian Americans 97 …IN TRANSLATION 8 | Between the Dollar and the Yen 109 9 | From Gifts to Commodities—and Back 121 10 | Salvage Rhythms: Business in Disturbance 131 INTERLUDE. TRACKING 137 PART III Disturbed Beginnings: Unintentional Design 149 11 | The Life of the Forest 155 COMING UP AMONG PINES … 12 | History 167 13 | Resurgence 179 14 | Serendipity 193 15 | Ruin 205 … IN GAPS AND PATCHES 16 | Science as Translation 217 17 | Flying Spores 227 INTERLUDE. -

University of California Santa Cruz Marxism

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA SANTA CRUZ MARXISM AND CONSTITUENT POWER IN LATIN AMERICA: THEORY AND HISTORY FROM THE MID-TWENTIETH CENTURY THROUGH THE PINK TIDE A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in HISTORY OF CONSCIOUSNESS with an emphasis in POLITICS by Robert Cavooris December 2019 The dissertation of Robert Cavooris is approved: _______________________________________ Robert Meister, Chair _______________________________________ Guillermo Delgado-P. _______________________________________ Juan Poblete _______________________________________ Megan Thomas _________________________________________ Quentin Williams Acting Vice Provost and Dean of Graduate Studies © Copyright by Robert Cavooris, 2019. All rights reserved. Table of Contents Abstract iv Acknowledgements and Dedication vi Preface x Introduction 1 Chapter 1 41 Intellectuals and Political Strategy: Hegemony, Posthegemony, and Post-Marxist Theory in Latin America Chapter 2 83 Constituent Power and Capitalism in the Works of René Zavaleta Mercado Chapter 3 137 Bolivian Insurgency and the Early Work of Comuna Chapter 4 204 Potentials and Limitations of the Bolivian ‘Process of Change’ Conclusions 261 Appendix: List of Major Works by Comuna (1999–2011) 266 Bibliography 271 iii Abstract Marxism and Constituent Power in Latin America: Theory and History from the Mid-Twentieth Century through The Pink Tide Robert Cavooris Throughout the history of Marxist theory and practice in Latin America, certain questions recur. What is the relationship between political and social revolution? How can state institutions serve as tools for political change? What is the basis for mass collective political agency? And how can intellectual work contribute to broader emancipatory political movements? Through textual and historical analysis, this dissertation examines how Latin American intellectuals and political actors have reframed and answered these questions in changing historical circumstances. -

Early Campus History

University of California, Santa Cruz University Library DEAN E. McHENRY VOLUME III UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SANTA CRUZ: EARLY CAMPUS HISTORY 1958-1969 Interviewed by Elizabeth Spedding Calciano Edited by E.S.C. and Randall Jarrell Santa Cruz 1987 ii Dean E. McHenry Inauguration as Chancellor University of California, Santa Cruz Upper Quarry May 3, 1966 iii All uses of this manuscript are covered by an agreement between the Regents of the University of California and Dean E. McHenry, dated February 20, 1971. The manuscript is thereby made available for research purposes upon his death unless he gives written permission to the Office of the University Librarian and/or the Office of the Regional History Project that the manuscript is to be available at an earlier date. With the exception of certain rights granted to Dean E. McHenry, all literary rights in the manuscript, including the right to publish, are reserved to The University Library of the University of California, Santa Cruz. No part of the manuscript may be quoted for publication without the written permission of the University Librarian of the University of California, Santa Cruz. iv TABLE OF CONTENTS Volume III INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................................................................... VIII JULY 10, 1968 9:45 A.M. ................................................................................................................................. 1 PROVOSTS ................................................................................................................................................................1 -

2017-2018 Academic Year 02

CELEBRATING THE HUMANITIES 2017-2018 Academic Year 02 LETTER FROM THE DEAN TYLER STOVALL As we come to the end of another academic year, many of us are no doubt grateful for the relative calm we have experienced since last year. National politics remains turbulent, but there have been no new changes or transitions comparable to those of a year ago. If last year was a time of drama, this has been more one of reassessment and new beginnings. It has been my pleasure to welcome new colleagues to the Humanities Division. History of Consciousness has two new faculty, Banu Bargu and Massimiliano Tomba, whose presence has brought new dynamism to the department. Ryan Bennett and Amanda Rysling joined the Linguistics department as assistant professors. I’m also pleased to welcome Literature professor Marlene Tromp, who so wanted to join us she consented to accept an administrative position as Campus Provost/Executive Vice Chancellor! At the same time, I must say farewell to some valued colleagues. Professors Tyrus Miller and Deanna Shemek are moving to faculty positions at UC Irvine, where Tyrus will also serve as Dean of the Humanities. Professors Bettina Aptheker, Jim McCloskey, and Karen Tei Yamashita retired from the university, although I hope they will remain active as emeriti faculty. Finally, I must acknowledge and mourn the passing of professor emeritus Hayden V. White. One of the most renowned and influential faculty members at UC Santa Cruz, Hayden White left a rich legacy to History of Consciousness, the Humanities, and UC Santa Cruz in general. This has also been a year of new initiatives. -

The UC Santa Cruz Budget – a Bird's Eye View

Office of Planning and Budget 2012-13 Edition The UC Santa Cruz Budget – A Bird’s Eye View Message from Office of Planning and Budget… December 2012 On behalf of the staff in Planning and Budget, I am happy to provide you with the 2012-13 edition of The Those birds have a good view of the budget. Birds Eye View. This document provides a unique look at the permanent operating budget for the campus and each of its major units. It includes recent data on the degrees conferred, the majors of our students, the number of faculty budgeted in each department, enrollments by department, and extramural awards. You can find it on the web at http://planning.ucsc.edu/budget/reports/birdseye. UCSC has implemented cuts in each of the past five years. While the cuts have been primarily in the core-funded areas, the impact has been felt throughout the campus. The passage of Proposition 30—and steps taken by the UC Office of the President to renew discussions with the State concerning the longer term funding needs of the University—represents the prospect for California to put public higher education back on a pathway toward fiscal stability. If the State and the UC Regents each agree on a multi-year financial plan for UC, this will create an opportunity for UCSC to create our own multi-year path. While additional cuts will be needed in 2013-14 to address the budget shortfall from 2012-13, we are cautiously optimistic that we can begin to plan for more budget stability. -

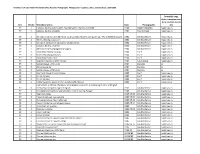

UA 128 Inventory Photographer Neg Slide Cs Series 8 16

Inventory: UA 128, Public Information Office Records: Photographs. Photographer negatives, slides, contact sheets, 1980-2005 Format(s): negs, slides, transparencies (trn), contact sheets Box Binder Title/Description Date Photographer (cs) 39 1 Campus, faculty and students. Marketing firm: Barton and Gillet. 1980 Robert Llewellyn negatives, cs 39 2 Campus, faculty, students 1984 Paul Schraub negatives, cs 39 2 Set construction; untitled Porter sculpture (aka"Wave"); computer lab; "Flying Weenies"poster 1984 Jim MacKenzie negatives, cs 39 2 Tennis, fencing; classroom 1984 Jim MacKenzie negatives, cs 39 2 Bike path; computers; costumes; sound system; 1984 Jim MacKenzie negatives, cs 39 2 Campus, faculty, students 1984 Jim MacKenzie negatives, cs 39 2 Admissions special programs (2 pages) 1984 Jim MacKenzie negatives, cs 39 3 Downtown family housing 1984 Joe ? negatives, cs 39 3 Student family apartments 1984 Joe ? negatives, cs 39 3 Downtown Santa Cruz 1984 Joe ? negatives, cs 39 3 Special Collections, UCSC Library 1984 Lucas Stang negatives, cs 39 3 Sailing classes, UCSC dock 1984 Dan Zatz cs 39 3 Childcare center 1984 Dan Zatz cs 39 3 Sailing classes, UCSC dock 1984 Dan Zatz cs 39 3 East Field House; Crown College 1985 Joe ? negatives, cs 39 3 Porter College 1985 Joe ? negatives, cs 39 3 Porter College 1985 Joe ? negatives, cs 39 3 Performing Arts; Oakes; Porter sculpture (The Wave) 1985 Joe ? negatives, cs Jack Schaar, professor of politics; Elena Baskin Visual Arts, printmaking studio; undergrad 39 3 chemistry; Computer engineering lab -

How Things Hold | 103

How Things Hold | 103 HOW THINGS HOLD A Diagram of Coordination in a Satoyama Forest Elaine Gan and Anna Tsing Abstract: This article experiments with combining three concepts— coordination, assemblage, diagram—to make vivid the composition of a satoyama forest in central Japan. The forest comes to life as a more-than-human assemblage that emerges through coordinations established by evolutionary and historical accommodations to life cycles, seasonal rhythms, and activity patterns. These coordinations are expressed through a diagram of intersecting temporalities of people, plants, and woodlands that condition the flourishing or decline of wild Social Analysis, Volume 62, Issue 4, Winter 2018, 102–145 © Berghahn Books doi:10.3167/sa.2018.620406 • ISSN 0155-977X (Print) • ISSN 1558-5727 (Online) 104 | Elaine Gan and Anna Tsing How Things Hold | 105 we parse temporal complexity and render interconnections more expressively? instructed us in how to read satoyama. This article, however, is not an ethnog- We turned to the diagram as a graphic form that might help us foreground raphy of the satoyama or the satoyama revitalization movement—a job better coordination and multispecies assemblage rather than autonomous humans. done elsewhere (e.g., Takeuchi et al. 2003). Our descriptions show the encoun- A diagram offers a critical description through selectivity and simplicity. ters through which the coordinations traced in our diagram arise. Ours draws from a legacy of attempts to illuminate worlds in motion. Paleo- Encounters across difference make and emerge from coordinations; the lithic cave paintings of Chauvet and Lascaux depict animals in superimposed researcher is also a party to such encounters. -

The Postmodern Condition: a Report on Knowledge

The Postlllodern Condition: A Report on Kno-wledge Jean-Fran�ois Lyotard Translation from the French by Geoff Bennington and Brian Massumi Foreword by Fredric Jameson Theory and History of Literature, Volume 10 £P Manchester University Press . .� � orip��?�;� l c.:�-•-"� t3o Thk book wu F �u rt�pport sur I� savoir, copyright© 1979 by Les Editions de Minuit. English translation and Foreword copyright© 1984 by the University of Minnesota. All rights reserved. Published in the United Kingdom by Manchester University Press. Oxford Road Manchester M13 9PL Printed in the United States of America. British LibruyCatalopaing in Publication Data Lyotard, jean-Fran�is The postmodem condition- (Theory and history of literature) 1. Knowledge, Theory of I. Title 11. La condition postmodeme. English Ill. Series 001 Z361 ISBN 0·7190-1454-9 ISBN o-7 1 90-1450-6 pbk. "Answering the Question : "What Is Postmodemism?" appears in this book counesy of the University of Wisconsin Press (English translation of this essay by Regis Durand copyright© 1983 by University of Wisconsin Press; the essay appears in lhab Hassan and Sally Hassan , eds., lnno11ation/R�no11ation !Madison: University of Wisconsin Press,198 3) ) and counesy of jean Piel, editor of Critiqu�. where the essay originally appeared as "Reponse a Ia question: qu'est-ce que le postmodc:rnc:?" in Critiqu�. number 419 (April 1982). Contents Foreword by Fredric jameson vii Introduction xxiii 1. The Field : Knowledge in Computerized Societies 3 2. The Problem : Legitimation 6 3. The Method: Language Games 9 4. The Nature of the Social Bond: The Modern Alternative 11 S. -

Anthropologies and Geographies of Globalization Katharine N

Progress in Human Geography 27,6 (2003) pp. 708–734 Anthropologies and geographies of globalization Katharine N. Rankin Department of Geography, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario, M5S 3G3, Canada Abstract: Anthropologists and geographers are increasingly turning to one another for tools to analyze the present global political-economic conjuncture. Yet to date there has been no adequate accounting of the comparative advantages each field brings to studies of globalization – Anthropology with its emphasis on the role of culture in anchoring (or resisting) globalizing processes within particular societies and Geography with its more comparative emphasis on the politics of place and scale. This paper is intended to contribute to interdisciplinary exchange through such an accounting and argues for a constructive synthesis geared toward understand- ing how ‘local’ cultural systems articulate with political-economic currents operating at wider spatial scales. Key words: globalization, anthropology, geography, culture, practice theory. IIntroduction Globalization is one of the few issues of our times that challenges the core identities of academic disciplines clear across the social, and indeed natural, sciences. Economists grapple with the growing contradictions between theories of economic ‘liberalization’ and mounting inequality and social unrest around the world; political scientists wonder whatever happened to the nation state as a viable political actor in its own right; and anthropologists rush to abandon characteristic ‘village studies’ in favor of more trendy explorations of ‘flows’, ‘border-crossings’ and ‘globalist projects’. The phenomenon of globalization threatens to rupture established boundaries between academic disciplines, as well as render irrelevant old modes of inquiry within them. The widespread unease that globalization provokes within academia can also be attributed to its prominence in public discourse. -

UC Santa Cruz Other Recent Work

UC Santa Cruz Other Recent Work Title The Critical World of Harry Berger, Jr.: An Oral History Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/4rg173mr Authors Vanderscoff, Cameron Reti, Irene Berger, Harry, Jr. Publication Date 2015-03-19 Supplemental Material https://escholarship.org/uc/item/4rg173mr#supplemental eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California The Critical World of Harry Berger, Jr.: An Oral History Interviewed by Cameron Vanderscoff Edited by Cameron Vanderscoff and Irene Reti Santa Cruz University of California, Santa Cruz University Library 2015 This oral history is covered by a copyright agreement between Harry Berger, Jr. and the Regents of the University of California dated March 2, 2015. Under “fair use” standards, excerpts of up to six hundred words (per interview) may be quoted without the University Library’s permission as long as the materials are properly cited. Quotations of more than six hundred words require the written permission of the Head of Special Collections and Archives and a proper citation and may also require a fee. Under certain circumstances, not-for-profit users may be granted a waiver of the fee. For permission contact: Irene Reti at [email protected], Oral Historian, Special Collections and Archives, McHenry Library, UC Santa Cruz, Santa Cruz, CA, 95064. Phone: 831-459-2847. Contents Interview History 1 Childhood: New York, New Rochelle 5 Education: High School, Yale and Early Writing 9 Anti-Semitism at Yale 12 Superheterodyne Radios, “Dickheads,” and Jazz in