Read It Here

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reality Television Participants As Limited-Purpose Public Figures

Vanderbilt Journal of Entertainment & Technology Law Volume 6 Issue 1 Issue 1 - Fall 2003 Article 4 2003 Almost Famous: Reality Television Participants as Limited- Purpose Public Figures Darby Green Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.vanderbilt.edu/jetlaw Part of the Privacy Law Commons Recommended Citation Darby Green, Almost Famous: Reality Television Participants as Limited-Purpose Public Figures, 6 Vanderbilt Journal of Entertainment and Technology Law 94 (2020) Available at: https://scholarship.law.vanderbilt.edu/jetlaw/vol6/iss1/4 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Vanderbilt Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Vanderbilt Journal of Entertainment & Technology Law by an authorized editor of Scholarship@Vanderbilt Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. All is ephemeral - fame and the famous as well. betrothal of complete strangers.' The Surreal Life, Celebrity - Marcus Aurelius (A.D 12 1-180), Meditations IV Mole, and I'm a Celebrity: Get Me Out of Here! feature B-list celebrities in reality television situations. Are You Hot places In the future everyone will be world-famous for fifteen half-naked twenty-somethings in the limelight, where their minutes. egos are validated or vilified by celebrity judges.' Temptation -Andy Warhol (A.D. 1928-1987) Island and Paradise Hotel place half-naked twenty-somethings in a tropical setting, where their amorous affairs are tracked.' TheAnna Nicole Show, the now-defunct The Real Roseanne In the highly lauded 2003 Golden Globe® and Show, and The Osbournes showcase the daily lives of Academy Award® winner for best motion-picture, Chicago foulmouthed celebrities and their families and friends. -

In Santa Monica...On Santa Monica” 888.203.8027

EKEND EDITI Whale of a story EE ON W N Visit us online smdp.com InsideInside ScoopScoop PAGE3PAGE3 a Santa Monica Daily Press January 13-14, 2007 A newspaper with issues Volume 6 Issue 53 DAILY LOTTERY BOTTOM DOLLAR 12 14 26 40 42 Meganumber: 22 Rise of Jackpot: $12M 6 10 20 42 45 Meganumber: 21 Jackpot: $9M the new 4 25 28 29 34 MIDDAY: 5 0 8 EVENING: 4 4 2 1st: 07 Eureka! Z-boys 2nd: 09 Winning Spirit 3rd: 05 California Classic RACE TIME: 1.49.65 Although every effort is made to ensure the accuracy of the winning number information, mistakes can occur. In the event of any discrepancies, California State laws and California Lottery regulations will prevail. Complete game information and prize claiming instructions are available at California Lottery retailers. Visit the California State Lottery web site at http://www.calottery.com in town BY MELODY HANATANI NEWS OF THE WEIRD Daily Press Staff Writer BY CHUCK SHEPARD Buddy, a 6-year-old German shepherd OCEAN PARK LIBRARY Taylor Lane mix, wandered into the emergency room and his friend Cory Micas look up to at the Kaiser Permanente Hospital in the guys who helped create the mod- Bellflower, Calif., in October after having just been hit by a car, and he resisted ern version of skateboarding and efforts to remove him, apparently wait- would like to see their history hon- ing until someone attended to his injured ored in a way befitting the Z-Boys. hind leg (which turned out to be broken), according to local animal control offi- Taking an interest in what might cials interviewed by the Whittier Daily become of the rundown building on News. -

Spring Fling

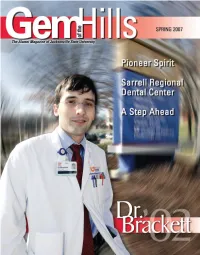

insurance administrator to human resources of the manager, all providing free services to GemThe Alumni Magazine of JacksonvilleHills State University deserving children with Medicaid or ALL- Vol. XIII, No. 2 KIDS insurance. Additional details about the JSU President dreams the center has and the ones they fulfill William A. Meehan, Ed.D., ’72/’76 are located on page 12. Vice President for Institutional Many patients at Erlanger Hospital in Advancement Chattanooga, Tenn. are also benefiting from Joseph A. Serviss, ’69/’75 a JSU alumnus thanks to the skills of Dr. Alumni Association President Stephen Brackett. The feature story on page Sarah Ballard,’69/’75/’82 15 tracks Brackett’s life from his decision to Director of Alumni Affairs and Editor attend JSU to his current life as a hospital Kaci Ogle, ’95/’04 resident. Art Director With a “STEP” in the right direction, Mary Smith, ’93 JSU’s College of Nursing and Health Sciences Staff Artists Dr. William A. Meehan, President Strategic Teaching for Enhanced Professional Erin Hill, ’01/’05 Preparation Program (page 18) is succeeding Rusty Hill in helping licensed RNs obtain higher Graham Lewis Dear Alumni, education goals while still fulfilling personal Copyeditor/Proofreader and occupational duties. Sybil Roark tells Gem Erin Chupp, ’05 In this issue, JSU alumni in healthcare how she returned to JSU for her master’s in Gloria Horton professions and the College of Nursing and nursing while working and raising children. In Staff Writers Health Sciences are highlighted as one of this article she explains how she searched for “a Al Harris, ’81/’91 the outstanding sectors of Jacksonville State quality education” and why JSU had “the best Anne Muriithi University. -

American Idol Trivia Quiz

AMERICAN IDOL TRIVIA QUIZ ( www.TriviaChamp.com ) 1> Which American Idol finalist was disqualified in season two due to his criminal record? a. Ace Young b. Corey Clark c. Lisa Tucker d. George Huff 2> In what year did the show American Idol debut? a. 2002 b. 1998 c. 2000 d. 2005 3> Who won American Idol season one? a. Ruben Studdard b. Kelly Clarkson c. George Tamyra d. Gray Huff 4> Which of these individuals was not among the finalists in season one? a. EJay Day b. Lee DeWyze c. Ryan Starr d. R.J.Helton 5> Which year did Steven Tyler become a judge on the hit show American Idol? a. 2005 b. 2011 c. 2007 d. 2009 6> Which of these people was not a judge on American Idol in season one? a. Ellen DeGeneres b. Simon Cowell c. Randy Jackson d. Paula Abdul 7> Who was the host of American Idol in the first season? a. Ryan Seacrest b. Simon Cowell c. Scotty McCreey d. Jim Verras 8> Which individual spoke out against American Idol on The Howard Stern show? a. Brian Dunkleman b. Bo Bice c. Randy Jackson d. Adam Lambert 9> Which American Idol finalist recorded the song Inside Your Heaven? a. Josh Gracin b. Blake Lewis c. Bo Bice d. Clay Aiken 10> Which American Idol finalist married hockey superstar Mike Fisher? a. Katherine McPhee b. Crystal Bowersox c. Carrie Underwood d. Lauren Alaina 11> Do I Make You Proud was written for which American Idol finalist? a. Jessica Sierra b. Taylor Hicks c. -

United States District Court Middle District of Tennessee Nashville Division

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT MIDDLE DISTRICT OF TENNESSEE NASHVILLE DIVISION COREY D. CLARK ) ) Plaintiff, ) ) v. ) No. 3:13-00058 ) Judge Sharp E! ENTERTAINMENT TELEVISION, ) LLC, and FOX BROADCASTING ) COMPANY, ) ) Defendants. ) MEMORANDUM After a final judgment was entered in accordance with this Court’s Order and Memorandum dismissing the Amended Complaint because Plaintiff’s claims were time-barred, Plaintiff Corey Clark filed a “Motion to Vacate the District Court’s Order and Judgment in its Entirety Pursuant to Rules 59 and 60.” (Docket No. 93). Defendants E! Entertainment Television LLC (“E!”) and Fox Broadcasting Company have filed responses in opposition, to which Plaintiff has replied. (Docket Nos. 95, 95 & 99). For the reasons that follow, the Court will grant Plaintiff’s Motion to Vacate and vacate the judgment that granted Defendants’ Motions to Dismiss, and dismissed this action on statute of limitations grounds. However, the Court will grant Fox’s Motion to Dismiss for failure to state a claim. The Court will also grant in part, and deny in part, E!’s Motion to Dismiss. I. MOTION TO VACATE In its Memorandum dismissing this case on statute of limitations grounds, the Court ruled: In Milligan v. United States, 670 F.3d 686, 698 (6th Cir. 2012), the Sixth Circuit stated that “Tennessee follows the single publication rule, meaning that a 1 Case 3:13-cv-00058 Document 100 Filed 10/10/14 Page 1 of 20 PageID #: <pageID> plaintiff’s cause of action accrues only once, at the time of publication, and later publications do not give rise to additional defamation causes of action,” and cited for that proposition Applewhite v. -

15A0490n.06 No. 14-5709 UNITED STATES COURT of APPEALS

NOT RECOMMENDED FOR PUBLICATION File Name: 15a0490n.06 No. 14-5709 UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT COREY D. CLARK; JAERED ANDREWS, ) ) Plaintiffs-Appellants, ) ) v. ) ON APPEAL FROM THE ) UNITED STATES DISTRICT VIACOM INTERNATIONAL INC.; VIACOM ) COURT FOR THE MIDDLE MEDIA NETWORKS; VIACOM, INC.; JIM ) DISTRICT OF TENNESSEE CANTIELLO; ) ) Defendants-Appellees. ) ) BEFORE: GRIFFIN and STRANCH, Circuit Judges; and STEEH, District Judge.* GRIFFIN, Circuit Judge. Almost a decade after Corey Clark and Jaered Andrews were publicly disqualified from participating on the television show American Idol, they filed a variety of defamation-related claims over statements contained in several online news articles that, over the years, had referenced their disqualifications. Ultimately, the district court dismissed all of the claims asserted in the complaint. This appeal raises two central questions. First, does the pertinent one-year statute of limitations permit Clark and Andrews to assert defamation claims with respect to statements that were posted to publicly accessible websites before the one-year limitations period but have *The Honorable George Caram Steeh III, United States District Judge for the Eastern District of Michigan, sitting by designation. No. 14-5709 Clark v. Viacom Int’l Inc. remained continuously accessible to the online public since then? And if not, have Clark and Andrews sufficiently pled defamation claims with respect to the statements that do fall within the limitations period? The answer to both questions is “no.” We therefore affirm the judgment of the district court. I. Ten years after his appearance in 2002 as a contestant on American Idol, Corey Clark filed a federal-court diversity action, alleging that numerous online statements made in MTV News and VH1 articles written by Jim Cantiello and other authors had defamed him and otherwise tortiously injured him over the preceding decade. -

Strategic Communication Efforts Surrounding American Idol's Loss

Volume 1 2012 www.csscjournal.org ISSN 2167-1974 Is Breaking Up Hard to Do?: Strategic Communication Efforts Surrounding American Idol’s Loss of Paula Abdul Sarah MacDonald Pepperdine University Emily S. Kinsky Kristina Drumheller West Texas A&M University Abstract The reality show American Idol has made its way to the top of television ratings in nearly all of its 11 seasons to date. However, a challenge came with the departure of original Idol judge Paula Abdul after unsuccessful contract negotiations in 2009. During the crisis, social media were filled with rumors and comments from disgruntled Abdul fans. This case study examines the strategic communication efforts of American Idol producers during this crisis. Image restoration methods by the producers are examined and suggestions are made for future similar crises. Keywords: reality television; Fox; Paula Abdul; American Idol; Twitter; social media; image restoration; celebrity; strategic communication The boom of reality television is, for the most part, a product of the new millennium. These productions are unpredictable, providing enough intrigue to keep viewers watching for an entire season (Consoli, 2001). It is a market known for the outrageous, volatile, and unpredictable contestants typically chosen by producers to draw a mass audience. Producers, hosts, and even scriptwriters welcome any media attention toward the contestants, regardless of the negative light commonly shed on these unassuming participants. To producers and promoters, any publicity that gets people talking about the show is good publicity. But what To cite this article MacDonald, S., Kinsky, E. S., & Drumheller, K. (2012). Is breaking up hard to do?: Strategic communication efforts surrounding American Idol’s loss of Paula Abdul. -

How American Idol Constructs Celebrity, Collective Identity, and American Discourses

AMERICAN IDEAL: HOW AMERICAN IDOL CONSTRUCTS CELEBRITY, COLLECTIVE IDENTITY, AND AMERICAN DISCOURSES A Dissertation Submitted to the Temple University Graduate Board In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy By Amanda Scheiner McClain May, 2010 i © Copyright 2010 by Amanda Scheiner McClain All Rights Reserved ii ABSTRACT This dissertation is a three-pronged study examining American themes, celebrity, and collective identity associated with the television program American Idol. The study includes discourse analyses of the first seven seasons of the program, of the season seven official American Idol message boards, and of the 2002 and 2008 show press coverage. The American themes included a rags-to-riches narrative, archetypes, and celebrity. The discourse-formed archetypes indicate which archetypes people of varied races may inhabit, who may be sexual, and what kinds of sexuality are permitted. On the show emotional exhibitions, archetypal resonance, and talent create a seemingly authentic celebrity while discourse positioning confirms this celebrity. The show also fostered a complication-free national American collective identity through the show discourse, while the online message boards facilitated the formation of two types of collective identities: a large group of American Idol fans and smaller contestant-affiliated fan groups. Finally, the press coverage study found two overtones present in the 2002 coverage, derision and awe, which were absent in the 2008 coverage. The primary reasons for this absence may be reluctance to criticize an immensely popular show and that the American Idol success was no longer surprising by 2008. By 2008, American Idol was so ingrained within American culture that to deride it was to critique America itself. -

List by Song Title

Song Title Artists 4 AM Goapele 73 Jennifer Hanson 1969 Keith Stegall 1985 Bowling For Soup 1999 Prince 3121 Prince 6-8-12 Brian McKnight #1 *** Nelly #1 Dee Jay Goody Goody #1 Fun Frankie J (Anesthesia) - Pulling Teeth Metallica (Another Song) All Over Again Justin Timberlake (At) The End (Of The Rainbow) Earl Grant (Baby) Hully Gully Olympics (The) (Da Le) Taleo Santana (Da Le) Yaleo Santana (Do The) Push And Pull, Part 1 Rufus Thomas (Don't Fear) The Reaper Blue Oyster Cult (Every Time I Turn Around) Back In Love Again L.T.D. (Everything I Do) I Do It For You Brandy (Get Your Kicks On) Route 66 Nat King Cole (Ghost) Riders In The Sky Johnny Cash (Goin') Wild For You Baby Bonnie Raitt (Hey Won't You Play) Another Somebody Done Somebody WrongB.J. Thomas Song (I Can't Get No) Satisfaction Otis Redding (I Don't Know Why) But I Do Clarence "Frogman" Henry (I Got) A Good 'Un John Lee Hooker (I Hate) Everything About You Three Days Grace (I Just Want It) To Be Over Keyshia Cole (I Just) Died In Your Arms Cutting Crew (The) (I Just) Died In Your Arms Cutting Crew (The) (I Know) I'm Losing You Temptations (The) (I Love You) For Sentimental Reasons Nat King Cole (I Love You) For Sentimental Reasons Nat King Cole (I Love You) For Sentimental Reasons ** Sam Cooke (If Only Life Could Be Like) Hollywood Killian Wells (If You're Not In It For Love) I'm Outta Here Shania Twain (If You're Not In It For Love) I'm Outta Here! ** Shania Twain (I'm A) Stand By My Woman Man Ronnie Milsap (I'm Not Your) Steppin' Stone Monkeys (The) (I'm Settin') Fancy Free Oak Ridge Boys (The) (It Must Have Been Ol') Santa Claus Harry Connick, Jr. -

Keeping It Real: a Historical Look at Reality TV

Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports 2011 Keeping It Real: A Historical Look at Reality TV Jessica Roberts West Virginia University Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd Recommended Citation Roberts, Jessica, "Keeping It Real: A Historical Look at Reality TV" (2011). Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports. 3438. https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd/3438 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by the The Research Repository @ WVU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you must obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in WVU Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports collection by an authorized administrator of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Keeping It Real: A Historical Look at Reality TV Jessica Roberts Thesis submitted to the P.I. Reed School of Journalism at West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Journalism Sara Magee, Ph.D., Chair Steve Urbanski, Ph.D. George Esper, Ph.D. Krystal Frazier, Ph.D. School of Journalism Morgantown, West Virginia 2011 Keywords: reality TV, challenge, talent, makeover, celebrity, product placement Copyright 2011 Jessica Roberts ABSTRACT Keeping It Real: A Historical Look at Reality TV Jessica Roberts In the summer of 2000 CBS launched a wilderness and competition reality show called “Survivor.” The show became a monster hit with more than fifty million viewers watching the finale, ratings only second to Super Bowl. -

Bird Flu Vaccine Now? More Than a Shot in the Dark Bob Marley Gets His

ALANBAA English28 Thursday, 12 July, 2012 Entertainment Health September 11 Bird flu vaccine now? attacks, Katrina top list of memorable More than a shot in the dark (Reuters) - Culls of hun- The scientific case for U.S. TV moments dreds of thousands of chick- pre-pandemic vaccination Victoria ens, turkeys and ducks to looks sound, given stud- (Reuters) - Watching news coverage of the stem bird flu outbreaks ies led by Karl Nichol- Beckham September 11 attacks, Hurricane Katrina disas- rarely make international son of Britain's Leicester ter, and the O.J. Simpson murder verdict proved headlines these days, but University showing that Happy Birthday, Harper Beck- to be the most impactful TV moments of the they are a worryingly com- even people immunized ham! David and Victoria’s past 50 years in the United States, according mon event as the deadly with a different flu strain Baby Turns 1 http://eonli.ne/ to a recent study. virus continues its march still had "immune mem- LEG2qL Television researcher Nielsen and Sony Elec- across the globe. ory" and some protection tronics partnered to find which TV events were As scientists delve deeper from a new virus many the most memorable for audiences. The Chal- into H5N1 avian influenza, years later. lenger space shuttle disaster in 1986 and death they have discovered it is "It's called the priming of Osama bin Laden rounded out the top five. only three steps way from effect," said Nikki Shindo, "What we were trying to measure was per- mutating into a potential- a medical officer in the de- ception," Paul Lindstrom, a senior vice presi- ly lethal human pandemic partment of pandemic and dent at Nielsen told Reuters. -

JB DB by Artist

Song Title …. Artists Drop (Dirty) …. 216 Hey Hey …. 216 Baby Come On …. (+44) When Your Heart Stops Beating …. (+44) 96 Tears …. ? & The Mysterians Rubber Bullets …. 10cc The Things We Do For Love …. 10cc The Things We Do For Love …. 10cc Come See Me …. 112' Cupid …. 112' Damn …. 112' Dance With Me …. 112' God Knows …. 112' I'm Sorry (Interlude) …. 112' Intro …. 112' Just A Little While …. 112' Just A Little While …. 112' Last To Know …. 112' Let This Go …. 112' Let This Go …. 112' Love Me …. 112' My Mistakes …. 112' Nowhere …. 112' Only You …. 112' Peaches & Cream …. 112' Peaches & Cream (Clean) …. 112' Peaches & Cream (Dirty) …. 112' Peaches & Cream (Inst) …. 112' That's How Close We Are …. 112' U Already Know …. 112' U Already Know …. 112' We Goin' Be Alright …. 112' What If …. 112' What The H**l Do You Want …. 112' Why Can't We Get Along …. 112' You Already Know (Clean) …. 112' Dance Wit Me (Remix) …. 112' (w Beanie Segal) It's Over (Remix) …. 112' (w G.Dep & Prodigy) The Way …. 112' (w Jermaine Dupri) Hot & Wet (Dirty) …. 112' (w Ludacris) Love Me …. 112' (w Mase) Only You …. 112' (w Notorious B.I.G.) Anywhere (Remix) …. 112' (w Shyne) If I Can Hit …. 112' (w T.I.) If I Hit …. 112' (w T.I.) Closing The Club …. 112' (w Three 6 Mafia) Dunkie Butt …. 12 Gauge Lie To Me …. 12 Stones 1, 2, 3 Red Light …. 1910 Fruitgum Co. Goody Goody Gumdrops …. 1910 Fruitgum Co. Indian Giver …. 1910 Fruitgum Co. Simple Simon Says …. 1910 Fruitgum Co. Simple Simon Says ….