Street Art and Mural Art As Visual Activism in Durban: 2014 – 2017

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

This Is Modern Art 2014/15 Season Lisa Portes Lisa

SAVERIO TRUGLIA PHOTOGRAPHY BY PHOTOGRAPHY BY 2014/15 SEASON STUDY GUIDE THIS IS MODERN ART (BASED ON TRUE EVENTS) WRITTEN BY IDRIS GOODWIN AND KEVIN COVAL DIRECTED BY LISA PORTES FEBRUARY 25 – MARCH 14, 2015 INDEX: 2 WELCOME LETTER 4 PLAY SYNOPSIS 6 COVERAGE OF INCIDENT AT ART INSTITUTE: MODERN ART. MADE YOU LOOK. 7 CHARACTER DESCRIPTIONS 8 PROFILE OF A GRAFFITI WRITER: MIGUEL ‘KANE ONE’ AGUILAR 12 WRITING ON THE WALL: GRAFFITI GIVES A VOICE TO THE VOICELESS with classroom activity 16 BRINGING CHICAGO’S URBAN LANDSCAPE TO THE STEPPENWOLF STAGE: A CONVERSATION WITH PLAYWRIGHT DEAR TEACHERS: IDRIS GOODWIN 18 THE EVOLUTION OF GRAFFITI IN THE UNITED STATES THANK YOU FOR JOINING STEPPENWOLF FOR YOUNG ADULTS FOR OUR SECOND 20 COMMON CORE STATE STANDARDS SHOW OF 2014/15 SEASON: CREATE A MOVEMENT: THE ART OF A REVOLUTION. 21 ADDITIONAL RESOURCES 22 NEXT UP: PROJECT COMPASS In This Is Modern Art, we witness a crew of graffiti writers, Please see page 20 for a detailed outline of the standards Made U Look (MUL), wrestling with the best way to make met in this guide. If you need further information about 23 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS people take notice of the art they are creating. They choose the way our work aligns with the standards, please let to bomb the outside of the Art Institute to show theirs is us know. a legitimate, worthy and complex art form born from a rich legacy, that their graffiti is modern art. As the character of As always, we look forward to continuing the conversations Seven tells us, ‘This is a chance to show people that there fostered on stage in your classrooms, through this guide are real artists in this city. -

When Art Is the Weapon: Culture and Resistance Confronting Violence in the Post-Uprisings Arab World

Religions 2015, 6, 1277–1313; doi:10.3390/rel6041277 OPEN ACCESS religions ISSN 2077-1444 www.mdpi.com/journal/religions Article When Art Is the Weapon: Culture and Resistance Confronting Violence in the Post-Uprisings Arab World Mark LeVine 1,2 1 Department of History, University of California, Irvine, Krieger Hall 220, Irvine, CA 92697-3275, USA; E-Mail: [email protected] 2 Center for Middle Eastern Studies, Lund University, Finngatan 16, 223 62 Lund, Sweden Academic Editor: John L. Esposito Received: 6 August 2015 / Accepted: 23 September 2015 / Published: 5 November 2015 Abstract: This article examines the explosion of artistic production in the Arab world during the so-called Arab Spring. Focusing on music, poetry, theatre, and graffiti and related visual arts, I explore how these “do-it-yourself” scenes represent, at least potentially, a “return of the aura” to the production of culture at the edge of social and political transformation. At the same time, the struggle to retain a revolutionary grounding in the wake of successful counter-revolutionary moves highlights the essentially “religious” grounding of “committed” art at the intersection of intense creativity and conflict across the Arab world. Keywords: Arab Spring; revolutionary art; Tahrir Square What to do when military thugs have thrown your mother out of the second story window of your home? If you’re Nigerian Afrobeat pioneer Fela Kuta, Africa’s greatest political artist, you march her coffin to the Presidential compound and write a song, “Coffin for Head of State,” about the murder. Just to make sure everyone gets the point, you use the photo of the crowd at the gates of the compound with her coffin as the album cover [1]. -

The Role of Political Art in the 2011 Egyptian Revolution

Resistance Graffiti: The Role of Political Art in the 2011 Egyptian Revolution Hayley Tubbs Submitted to the Department of Political Science Haverford College In partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts Professor Susanna Wing, Ph.D., Advisor 1 Acknowledgments I would like to extend my heartfelt gratitude to Susanna Wing for being a constant source of encouragement, support, and positivity. Thank you for pushing me to write about a topic that simultaneously scared and excited me. I could not have done this thesis without you. Your advice, patience, and guidance during the past four years have been immeasurable, and I cannot adequately express how much I appreciate that. Thank you, Taieb Belghazi, for first introducing me to the importance of art in the Arab Spring. This project only came about because you encouraged and inspired me to write about political art in Morocco two years ago. Your courses had great influence over what I am most passionate about today. Shukran bzaf. Thank you to my family, especially my mom, for always supporting me and my academic endeavors. I am forever grateful for your laughter, love, and commitment to keeping me humble. 2 Table of Contents Acknowledgements……………………………………………………....…………. 1 Introduction…………………………………………………………………….……..3 The Egyptian Revolution……………………………………………………....6 Limited Spaces for Political Discourse………………………………………...9 Political Art………………………………………………………………..…..10 Political Art in Action……………………………………………………..…..13 Graffiti………………………………………………………………………....14 Conclusion…………………………………………………………………......19 -

Juliana Abramides Dos Santos.Pdf

PONTIFÍCIA UNIVERSIDADE CATÓLICA DE SÃO PAULO PUC-SP Juliana Abramides dos Santos Arte urbana no capitalismo em chamas: pixo e graffiti em explosão DOUTORADO EM SERVIÇO SOCIAL SÃO PAULO 2019 Juliana Abramides dos Santos DOUTORADO EM SERVIÇO SOCIAL Tese apresentada à Banca Examinadora da Pontifícia Universidade Católica de São Paulo, como exigência parcial para obtenção do título de Doutora em Serviço Social sob a orientação do Prof. Dr. Antônio Carlos Mazzeo. 2019 Autorizo exclusivamente para fins acadêmicos e científicos, a reprodução total ou parcial desta tese de doutorado por processos de fotocopiadoras ou eletrônicos. Assinatura: Data: E-mail: Ficha Catalográfica dos SANTOS, JULIANA Abramides Arte urbana no capitalismo em chamas: pixo e graffiti em explosão / JULIANA Abramides dos SANTOS. -- São Paulo: [s.n.], 2019. 283p. il. ; cm. Orientador: Antônio Carlos Mazzeo. Co-Orientador: Kevin B. Anderson. Tese (Doutorado em Serviço Social)-- Pontifícia Universidade Católica de São Paulo, Programa de Estudos Pós-Graduados em Serviço Social, 2019. 1. Arte Urbana. 2. Capitalismo Contemporâneo. 3. Pixo. 4. Graffiti. I. Mazzeo, Antônio Carlos. II. Pontifícia Universidade Católica de São Paulo, Programa de Estudos Pós-Graduados em Serviço Social. III. Título.I. Mazzeo, Antônio Carlos. II. Anderson, Kevin B., co-orient. IV. Título. Banca Examinadora ------------------------------------- ------------------------------------- ------------------------------------- ------------------------------------- ------------------------------------- Aos escritores/as e desenhistas do fluxo de imagens urbanas. O presente trabalho foi realizado com apoio do Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq) - Número do Processo- 145851/2015-0. This study was financed in part by the Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq) - Finance Code 001-145851/2015-0. Esta tese de doutorado jamais poderia ser escrita sem o contato e apoio de inúmeras parcerias. -

State Violence, Mobility and Everyday Life in Cairo, Egypt

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--Geography Geography 2015 State Violence, Mobility and Everyday Life in Cairo, Egypt Christine E. Smith University of Kentucky, [email protected] Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Smith, Christine E., "State Violence, Mobility and Everyday Life in Cairo, Egypt" (2015). Theses and Dissertations--Geography. 34. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/geography_etds/34 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Geography at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--Geography by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained needed written permission statement(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine) which will be submitted to UKnowledge as Additional File. I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the irrevocable, non-exclusive, and royalty-free license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. I agree that the document mentioned above may be made available immediately for worldwide access unless an embargo applies. -

16 IMPROVISATORY PEACE ACTIVISM? Graffiti During and After Egypt’S Most Recent Revolution1

16 IMPROVISATORY PEACE ACTIVISM? Graffiti during and after Egypt’s most recent revolution1 Asif Majid On January 27, 2011, just two days after the start of massive protests against Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak in Cairo’s Tahrir Square, artist Ganzeer released a pamphlet entitled “How to Revolt Intelligently.”2 Circulated by email—and on paper, after the Egyptian government shut down the internet on January 28—the pamphlet highlighted what protesters should wear to protect their bodies (hooded sweatshirts, thick gloves, protective glasses, and running shoes), what to carry to spread their message (spray paint for police visors, pot lids as shields, and a rose for peace), and how to combat police personnel and vehicles (Figure 16.1a, b). Political scientist and blogger As’ad AbuKhalil later described the pamphlet as “the most sophisticated manual by activists that I have seen” complete with “well-done illustration.”3 Indeed, Ganzeer’s pamphlet echoed German studies scholar Edgar Landgraf’s framing of improvisation as “a basic means for the affirmation of agency and even survival in a society that has become utterly unpredictable.”4 Prior to the January 2011 protests, basic survival in Egyptian society had grown increasingly difficult. Economically, prices for staple goods such as bread and fruit had skyrocketed while the minimum wage had remained stagnant since 1984. Additionally, though increasing numbers of youth had access to education, 700,000 annual university graduates pursued only 200,000 new jobs every year.5 Wealth was concentrated in the hands of the few at the expense of the many; six men owned 4.3 percent of the country’s wealth while 25 percent of the country lived below the poverty line.6 Politically, the Mubarak regime had long maintained a state of emergency, contributing to a concentration of power that enabled Mubarak to appoint and remove the prime minister, Council of Ministers, governors, mayors, and deputy mayors at will. -

Arab Media & Society (Issue 23, Winter/Spring 2017)

Arab Media & Society (Issue 23, Winter/Spring 2017) Revolutionary Art or “Revolutonizing Art”? Making Art on the Streets of Cairo Rounwah Adly Riyadh Bseiso In an article published on December 17, 2014, Surti Singh, an Assistant Professor of Philosophy at the American University in Cairo (AUC), wrote that “a new set of questions is crystallizing about the role of art in contemporary Egypt” and posed the following questions: “Can art still preserve the revolutionary spirit that spilled out in the graffiti and murals that covered Egypt’s streets? Should this even be art’s focus?” (Singh, 2014). Singh’s questions at the time were indicative of a growing debate in Egypt over what constitutes a legitimate “art” and what its focus should be following the uprising of January 2011, given the emergence of new forms of art in public spaces. Public art is not a new phenomenon in Egypt – its modern history goes back to the late 19th century (Karnouk 2005; Winegar 2006), and street art also has a history prior to the uprising in Egypt (Charbel 2010; Jarbou 2010; Hamdy et.al 2014, Abaza, 2016). However, the form, content and even the players of public art and street art have changed as practices have become more visible and with this visibility come new questions – what is the role of art in uprising and post-uprising Egypt? Should art incite the public to act against a repressive government, should it serve as a form of awareness, and/or should it document the revolutions “real” history versus what is reported in state media? Is overtly “political” art serving the “revolution” or undermining it? Is aesthetically pleasing, but seemingly content deprived art, a disservice to the revolution? Ganzeer, one of the most well-known artists of the uprising, writes: …there are a bunch of thirty-something artists in Egypt today who think of themselves as cutting edge for adopting a 1917 [citing Marcel Duchamp’s ‘Fountain’ as the example] art form that most Egyptians do not relate to – they adopt it anyway out of an urge to appeal to art institutions centered in Europe and the USA. -

Beyond Guernica and the Guggenheim

Beyond Guernica and the Guggenheim Beyond Art and Politics from a Comparative Perspective a Comparative from Art and Politics Beyond Guernica and the Guggenheim This book brings together experts from different fields of study, including sociology, anthropology, art history Art and Politics from a Comparative Perspective and art criticism to share their research and direct experience on the topic of art and politics. How art and politics relate with each other can be studied from numerous perspectives and standpoints. The book is structured according to three main themes: Part 1, on Valuing Art, broadly concerns the question of who, how and what value is given to art, and how this may change over time and circumstance, depending on the social and political situation and motivation of different interest groups. Part 2, on Artistic Political Engagement, reflects on another dimension of art and politics, that of how artists may be intentionally engaged with politics, either via their social and political status and/or through the kind of art they produce and how they frame it in terms of meaning. Part 3, on Exhibitions and Curating, focuses on yet another aspect of the relationship between art and politics: what gets exhibited, why, how, and with what political significance or consequence. A main focus is on the politics of art in the Basque Country, complemented by case studies and reflections from other parts of the world, both in the past and today. This book is unique by gathering a rich variety of different viewpoints and experiences, with artists, curators, art historians, sociologists and anthropologists talking to each other with sometimes quite different epistemological bases and methodological approaches. -

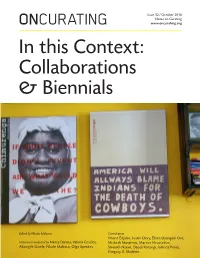

In This Context: Collaborations & Biennials

Issue 32 / October 2016 Notes on Curating ONCURATING www.oncurating.org In this Context: Collaborations & Biennials Edited by Nkule Mabaso Contributors Ntone Edjabe, Justin Davy, Elvira Dyangani Ose, Interviews conducted by Nancy Dantas, Valeria Geselev, Misheck Masamvu, Marcus Neustetter, Abongile Gwele, Nkule Mabaso, Olga Speakes Smooth Nzewi, Daudi Karungi, Iolanda Pensa, Gregory G. Sholette Contents 02 Editorial Nkule Mabaso INTERVIEWS ON COLLABORATIONS INTERVIEWS ON BIENNIALS 09 55 Ntone Edjabe of Chimurenga Smooth Nzewi interviewed by Valeria Geselev interviewed by Nkule Mabaso 13 62 Justin Davy of Burning Museum Daudi Karungi interviewed by Nancy Dantas interviewed by Nkule Mabaso 19 65 Gregory Sholette Misheck Masamvu interviewed by Nkule Mabaso interviewed by Olga Speakes 24 Marcus Neustetter of On Air 70 interviewed by Abongile Gwele Imprint PAPERS 33 Counting On Your Collective Silence by Gregory G. Sholette 43 For Whom Are Biennials Organized? by Elvira Dyangani Ose 48 Public Art and Urban Change in Douala by Iolanda Pensa Editorial In this Context: Collaborations & Biennials Editorial Nkule Mabaso This issue of OnCurating consists of two parts: the first part researches collaborative work with an emphasis on African collectives, and the second part offers an insight into the development of biennials on the African continent. Part 1 Collaboration Is collaboration an inherently ‘better’ method, producing ‘better’ results? The curatorial collective claims that the purpose of collaboration lies in producing something that would -

Exploring the Role of Mural Art in Architecture As a Catalyst for Social Revitalisation

EXPLORING THE ROLE OF MURAL ART IN ARCHITECTURE AS A CATALYST FOR SOCIAL REVITALISATION Towards the Design of an Art Centre for the City of Durban By Julie Ann Language Supervisor Mr Juan Ignacio Solis-Arias Dissertation submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Architecture to The School of the Built Environment and Development Studies University of KwaZulu-Natal Durban, South Africa October 2015 DECLARATION - PLAGIARISM I, Julie Ann Language, declare that 1. The research reported in this thesis, except where otherwise indicated, is my original research. 2. This thesis has not been submitted for any degree or examination at any other university. 3. This thesis does not contain other persons’ data, pictures, graphs or other information, unless specifically acknowledged as being sourced from other persons. 4. This thesis does not contain other persons' writing, unless specifically acknowledged as being sourced from other researchers. Where other written sources have been quoted, then: a. Their words have been re-written but the general information attributed to them has been referenced b. Where their exact words have been used, then their writing has been placed in italics and inside quotation marks, and referenced. 5. This thesis does not contain text, graphics or tables copied and pasted from the Internet, unless specifically acknowledged, and the source being detailed in the thesis and in the References sections. _____________________________ i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am forever thankful to my parents, brothers and my fiancé. Gary, Lynda, Wesley, Brett and Chris, without your continuing love, patience, encouragement and support, I would not be where I am today. -

An Investigation of Urban Artists’ Mobilizing Power in Oaxaca and Mexico City

THE UNOFFICIAL STORY AND THE PEOPLE WHO PAINT IT: AN INVESTIGATION OF URBAN ARTISTS’ MOBILIZING POWER IN OAXACA AND MEXICO CITY by KENDRA SIEBERT A THESIS Presented to the Department of Journalism and Communication and the Robert D. Clark Honors College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts June 2019 An Abstract of the Thesis of Kendra Siebert for the degree of Bachelor of Arts in the Department of Journalism and Communication to be taken June 2019 Title: The Unofficial Story and the People Who Paint It: An Investigation of Urban Artists’ Mobilizing Power in Oaxaca and Mexico City Approved: _______________________________________ Peter Laufer Although parietal writing – the act of writing on walls – has existed for thousands of years, its contemporary archetype, urban art, emerged much more recently. An umbrella term for the many kinds of art that occupy public spaces, urban art can be accessed by whoever chooses to look at it, and has roots in the Mexican muralism movement that began in Mexico City and spread to other states like Oaxaca. After the end of the military phase of the Mexican Revolution in the 1920s, philosopher, writer and politician José Vasconcelos was appointed to the head of the Mexican Secretariat of Public Education. There, he found himself leading what he perceived to be a disconnected nation, and believed visual arts would be the means through which to unify it. In 1921, Vasconcelos proposed the implementation of a government-funded mural program with the intent of celebrating Mexico and the diverse identities that comprised it. -

Conservation of Urban Art

CONSERVATION OF URBAN ART COATINGS AND GREEN CLEANING METHODS FOR VANDALIZED URBAN ART MURALS IN ITALY AND PORTUGAL Dissertation presented to Universidade Católica Portuguesa to obtain the degree of Master in Conservation and Restoration in Cultural Heritage Margarida Santos Jesus de Castro Porto | 2020 CONSERVATION OF URBAN ART COATINGS AND GREEN CLEANING METHODS FOR VANDALIZED URBAN ART MURALS IN ITALY AND PORTUGAL Dissertation presented to Universidade Católica Portuguesa to obtain the degree of Master in Conservation and Restoration in Cultural Heritage Integrated Heritage Margarida Santos Jesus de Castro Dissertation under the supervision of Doctor Patrícia Moreira And co-supervision of Doctor Eduarda Vieira Doctor Andrea Macchia Porto | 2020 To my grandmother, my mother, my father and my sister. i ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Certain people, to whom I would like to address a few words of gratitude, that were so important in carrying out this dissertation. To my supervisor, Professor Patrícia Moreira, and co-supervisors, Professor Eduarda Vieira and Professor Andrea Macchia for their continuous and incessant support, for the enormous availability and knowledge sharing shared throughout this research. To the Università Sapienza di Roma and the YOCOCU entity, especially to Laura Rivaroli, for the warm welcome in Rome and sharing of knowledge essential to this study. To the Mariano Davoli of Università della Calabria and to Daniela Ferro of Museo delle Cività in Rome for the material characterization carried out in the research. To my colleagues and friends who have accompanied and motivated me throughout my academic career. Special thanks are given to my family, Isabel, Nelson and Catarina for encouraging me to proceed with my interests, supporting me in the most difficult situations and for employing me, providing me funding I needed to this research.