Arab Media & Society (Issue 23, Winter/Spring 2017)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

When Art Is the Weapon: Culture and Resistance Confronting Violence in the Post-Uprisings Arab World

Religions 2015, 6, 1277–1313; doi:10.3390/rel6041277 OPEN ACCESS religions ISSN 2077-1444 www.mdpi.com/journal/religions Article When Art Is the Weapon: Culture and Resistance Confronting Violence in the Post-Uprisings Arab World Mark LeVine 1,2 1 Department of History, University of California, Irvine, Krieger Hall 220, Irvine, CA 92697-3275, USA; E-Mail: [email protected] 2 Center for Middle Eastern Studies, Lund University, Finngatan 16, 223 62 Lund, Sweden Academic Editor: John L. Esposito Received: 6 August 2015 / Accepted: 23 September 2015 / Published: 5 November 2015 Abstract: This article examines the explosion of artistic production in the Arab world during the so-called Arab Spring. Focusing on music, poetry, theatre, and graffiti and related visual arts, I explore how these “do-it-yourself” scenes represent, at least potentially, a “return of the aura” to the production of culture at the edge of social and political transformation. At the same time, the struggle to retain a revolutionary grounding in the wake of successful counter-revolutionary moves highlights the essentially “religious” grounding of “committed” art at the intersection of intense creativity and conflict across the Arab world. Keywords: Arab Spring; revolutionary art; Tahrir Square What to do when military thugs have thrown your mother out of the second story window of your home? If you’re Nigerian Afrobeat pioneer Fela Kuta, Africa’s greatest political artist, you march her coffin to the Presidential compound and write a song, “Coffin for Head of State,” about the murder. Just to make sure everyone gets the point, you use the photo of the crowd at the gates of the compound with her coffin as the album cover [1]. -

The Role of Political Art in the 2011 Egyptian Revolution

Resistance Graffiti: The Role of Political Art in the 2011 Egyptian Revolution Hayley Tubbs Submitted to the Department of Political Science Haverford College In partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts Professor Susanna Wing, Ph.D., Advisor 1 Acknowledgments I would like to extend my heartfelt gratitude to Susanna Wing for being a constant source of encouragement, support, and positivity. Thank you for pushing me to write about a topic that simultaneously scared and excited me. I could not have done this thesis without you. Your advice, patience, and guidance during the past four years have been immeasurable, and I cannot adequately express how much I appreciate that. Thank you, Taieb Belghazi, for first introducing me to the importance of art in the Arab Spring. This project only came about because you encouraged and inspired me to write about political art in Morocco two years ago. Your courses had great influence over what I am most passionate about today. Shukran bzaf. Thank you to my family, especially my mom, for always supporting me and my academic endeavors. I am forever grateful for your laughter, love, and commitment to keeping me humble. 2 Table of Contents Acknowledgements……………………………………………………....…………. 1 Introduction…………………………………………………………………….……..3 The Egyptian Revolution……………………………………………………....6 Limited Spaces for Political Discourse………………………………………...9 Political Art………………………………………………………………..…..10 Political Art in Action……………………………………………………..…..13 Graffiti………………………………………………………………………....14 Conclusion…………………………………………………………………......19 -

Juliana Abramides Dos Santos.Pdf

PONTIFÍCIA UNIVERSIDADE CATÓLICA DE SÃO PAULO PUC-SP Juliana Abramides dos Santos Arte urbana no capitalismo em chamas: pixo e graffiti em explosão DOUTORADO EM SERVIÇO SOCIAL SÃO PAULO 2019 Juliana Abramides dos Santos DOUTORADO EM SERVIÇO SOCIAL Tese apresentada à Banca Examinadora da Pontifícia Universidade Católica de São Paulo, como exigência parcial para obtenção do título de Doutora em Serviço Social sob a orientação do Prof. Dr. Antônio Carlos Mazzeo. 2019 Autorizo exclusivamente para fins acadêmicos e científicos, a reprodução total ou parcial desta tese de doutorado por processos de fotocopiadoras ou eletrônicos. Assinatura: Data: E-mail: Ficha Catalográfica dos SANTOS, JULIANA Abramides Arte urbana no capitalismo em chamas: pixo e graffiti em explosão / JULIANA Abramides dos SANTOS. -- São Paulo: [s.n.], 2019. 283p. il. ; cm. Orientador: Antônio Carlos Mazzeo. Co-Orientador: Kevin B. Anderson. Tese (Doutorado em Serviço Social)-- Pontifícia Universidade Católica de São Paulo, Programa de Estudos Pós-Graduados em Serviço Social, 2019. 1. Arte Urbana. 2. Capitalismo Contemporâneo. 3. Pixo. 4. Graffiti. I. Mazzeo, Antônio Carlos. II. Pontifícia Universidade Católica de São Paulo, Programa de Estudos Pós-Graduados em Serviço Social. III. Título.I. Mazzeo, Antônio Carlos. II. Anderson, Kevin B., co-orient. IV. Título. Banca Examinadora ------------------------------------- ------------------------------------- ------------------------------------- ------------------------------------- ------------------------------------- Aos escritores/as e desenhistas do fluxo de imagens urbanas. O presente trabalho foi realizado com apoio do Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq) - Número do Processo- 145851/2015-0. This study was financed in part by the Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq) - Finance Code 001-145851/2015-0. Esta tese de doutorado jamais poderia ser escrita sem o contato e apoio de inúmeras parcerias. -

State Violence, Mobility and Everyday Life in Cairo, Egypt

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--Geography Geography 2015 State Violence, Mobility and Everyday Life in Cairo, Egypt Christine E. Smith University of Kentucky, [email protected] Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Smith, Christine E., "State Violence, Mobility and Everyday Life in Cairo, Egypt" (2015). Theses and Dissertations--Geography. 34. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/geography_etds/34 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Geography at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--Geography by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained needed written permission statement(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine) which will be submitted to UKnowledge as Additional File. I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the irrevocable, non-exclusive, and royalty-free license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. I agree that the document mentioned above may be made available immediately for worldwide access unless an embargo applies. -

16 IMPROVISATORY PEACE ACTIVISM? Graffiti During and After Egypt’S Most Recent Revolution1

16 IMPROVISATORY PEACE ACTIVISM? Graffiti during and after Egypt’s most recent revolution1 Asif Majid On January 27, 2011, just two days after the start of massive protests against Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak in Cairo’s Tahrir Square, artist Ganzeer released a pamphlet entitled “How to Revolt Intelligently.”2 Circulated by email—and on paper, after the Egyptian government shut down the internet on January 28—the pamphlet highlighted what protesters should wear to protect their bodies (hooded sweatshirts, thick gloves, protective glasses, and running shoes), what to carry to spread their message (spray paint for police visors, pot lids as shields, and a rose for peace), and how to combat police personnel and vehicles (Figure 16.1a, b). Political scientist and blogger As’ad AbuKhalil later described the pamphlet as “the most sophisticated manual by activists that I have seen” complete with “well-done illustration.”3 Indeed, Ganzeer’s pamphlet echoed German studies scholar Edgar Landgraf’s framing of improvisation as “a basic means for the affirmation of agency and even survival in a society that has become utterly unpredictable.”4 Prior to the January 2011 protests, basic survival in Egyptian society had grown increasingly difficult. Economically, prices for staple goods such as bread and fruit had skyrocketed while the minimum wage had remained stagnant since 1984. Additionally, though increasing numbers of youth had access to education, 700,000 annual university graduates pursued only 200,000 new jobs every year.5 Wealth was concentrated in the hands of the few at the expense of the many; six men owned 4.3 percent of the country’s wealth while 25 percent of the country lived below the poverty line.6 Politically, the Mubarak regime had long maintained a state of emergency, contributing to a concentration of power that enabled Mubarak to appoint and remove the prime minister, Council of Ministers, governors, mayors, and deputy mayors at will. -

Beyond Guernica and the Guggenheim

Beyond Guernica and the Guggenheim Beyond Art and Politics from a Comparative Perspective a Comparative from Art and Politics Beyond Guernica and the Guggenheim This book brings together experts from different fields of study, including sociology, anthropology, art history Art and Politics from a Comparative Perspective and art criticism to share their research and direct experience on the topic of art and politics. How art and politics relate with each other can be studied from numerous perspectives and standpoints. The book is structured according to three main themes: Part 1, on Valuing Art, broadly concerns the question of who, how and what value is given to art, and how this may change over time and circumstance, depending on the social and political situation and motivation of different interest groups. Part 2, on Artistic Political Engagement, reflects on another dimension of art and politics, that of how artists may be intentionally engaged with politics, either via their social and political status and/or through the kind of art they produce and how they frame it in terms of meaning. Part 3, on Exhibitions and Curating, focuses on yet another aspect of the relationship between art and politics: what gets exhibited, why, how, and with what political significance or consequence. A main focus is on the politics of art in the Basque Country, complemented by case studies and reflections from other parts of the world, both in the past and today. This book is unique by gathering a rich variety of different viewpoints and experiences, with artists, curators, art historians, sociologists and anthropologists talking to each other with sometimes quite different epistemological bases and methodological approaches. -

The Political Aesthetics of Global Protest : the Arab Spring and Beyond, P

eCommons@AKU Individual Volumes ISMC Series 2014 The olitP ical Aesthetics of Global Protest : the Arab Spring and Beyond Pnina Werbner Editor Martin Webb Editor Kathryn Spellman-Poots Editor Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.aku.edu/uk_ismc_series_volumes Part of the African History Commons, Asian History Commons, Islamic World and Near East History Commons, and the Political History Commons Recommended Citation Werbner, P. , Webb, M. , Spellman-Poots, K. (Eds.). (2014). The Political Aesthetics of Global Protest : the Arab Spring and Beyond, p. 448. Available at: https://ecommons.aku.edu/uk_ismc_series_volumes/3 The Political Aesthetics of Global Protest The Arab Spring and Beyond Edited by Pnina Werbner, Martin Webb and Kathryn Spellman-Poots in association with THE AGA KHAN UNIVERSITY (International) in the United Kingdom Institute for the Study of Muslim Civilisations The opinions expressed in this volume are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Aga Khan University, Institute for the Study of Muslim Civilisations. © editorial matter and organisation Pnina Werbner, Martin Webb and Kathryn Spellman-Poots, 2014 © the chapters, their several authors, 2014 First published in hardback in 2014 by Edinburgh University Press Ltd The Tun – Holyrood Road 12 (2f) Jackson’s Entry Edinburgh eh8 8pj www.euppublishing.com Typeset in Goudy Oldstyle by Koinonia, Manchester and printed and bound in Spain by Novoprint A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 978 0 7486 9334 4 (hardback) ISBN 978 0 7486 9335 1 (paperback) ISBN 978 0 7486 9350 4 (webready PDF) ISBN 978 0 7486 9351 1 (epub) The right of the contributors to be identified as authors of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 and the Copyright and Related Rights Regulations 2003 (SI No. -

A Case Study of Women and Graffiti in Egypt

Re-Defining Revolution: A Case Study of Women and Graffiti in Egypt by Stephanie Perrin B.A., Ryerson University, 2012 Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the School of International Studies Faculty of Arts and Sciences Stephanie Perrin 2015 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Fall 2015 Approval Name: Stephanie Jane Perrin Degree: Master of Arts (International Studies) Title: Re-Defining Revolution: A Case Study of Women and Graffiti in Egypt Examining Committee: Chair: Dr. Christopher Gibson Assistant Professor Dr. Tamir Moustafa Senior Supervisor Associate Professor Dr. Alexander Dawson Supervisor Professor Department of History Dr. Judith Marcuse External Examiner Adjunct Professor Faculty of Education Date Defended/Approved: 2 December, 2015 ii Abstract Like any social phenomenon, revolutions are gendered. The male tilt of revolutionary processes and their histories has produced a definition of revolution that consistently fails women. This thesis aims to redefine revolution to incorporate women’s visions of societal transformation and the full achievement of their rights and freedoms. I argue that approaches to women’s revolutionary experiences are enriched by focusing on the roles of culture, consciousness, and unconventional revolutionary texts. Egypt is examined as a case study with a focus on the nation’s long history of women’s activism that took on new forms in the wave of socio-political upheaval since 2011. Using interdisciplinary, visual analysis, I examine graffiti created by women, or that depict women between 2011 and 2015 to reveal how gender was publicly re-imagined during a period of flux for Egyptian society. The historical and visual analysis contribute to a new definition of revolution, one that strives to achieve the total transformation of society by disrupting gendered consciousness to finally secure rights and freedoms for all. -

Imaging Egypt's Political Transition

Imaging Egypt’s Political Transition in (Post-)Revolutionary Street Art Adrienne de Ruiter 3069052 Utrecht University 30 July 2012 A thesis submitted to the Board of Examiners in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Arts in Conflict Studies & Human Rights Supervisor: Dr. Jolle Demmers Date of submission: 30 July 2012 Programme trajectory: Research & Thesis Writing only (30 ECTS) Word count: 25.982 The photograph on the cover shows a detail from a piece of street art about people’s participation in the Egyptian revolution by Alaa Awad. (Photograph by Adrienne de Ruiter) Abstract This thesis offers a conceptualisation of the interrelations between street art and social media within the temporal and spatial context of (post-)revolutionary Cairo by focusing on the reasons as to why street artists in Cairo select graffiti as their medium for political expression in a time in which many other media of communication, most notably social media, are available. Based upon in-depth interviews with Cairene street artists, on the one hand, and a literature study on the concepts of collective action framing, contentious performances and the relation between the political and the aesthetic, on the other, this thesis provides an analysis of (post-)revolutionary street art in Cairo that seeks to clarify why certain politically engaged young people in Cairo select graffiti as the medium of communication to make their political voices heard. It is argued that the particular appeal of street art for the graffiti artist lies in its ability to function simultaneously as a medium of communication and a contentious performance, combined with the particular power of the aesthetic to change conceptions of social reality of the audience through what Jacques Rancière has called the distribution of the sensible. -

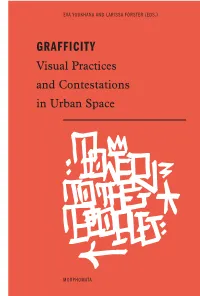

Grafficity Visual Practices and Contestations in Urban Space

EVA YOUKHANA AND LARISSA FÖRSTER (EDS.) GRAFFICITY Visual Practices and Contestations in Urban Space MORPHOMATA Graffiti has its roots in urban youth and protest cul- tures. However, in the past decades it has become an established visual art form. This volume investigates how graffiti oscillates between genuine subversiveness and a more recent commercialization and appropria- tion by the (art) market. At the same time it looks at how graffiti and street art are increasingly used as an instrument for collective re-appropriation of the urban space and so for the articulation of different forms of belonging, ethnicity, and citizenship. The focus is set on the role of graffiti in metropolitan contexts in the Spanish-speaking world but also includes glimpses of historical inscriptions in ancient Rome and Meso- america, as well as the graffiti movement in New York in the 1970s and in Egypt during the Arab Spring. YOUKHANA, FÖRSTER (EDS.) — GRAFFICITY MORPHOMATA EDITED BY GÜNTER BLAMBERGER AND DIETRICH BOSCHUNG VOLUME 28 EDITED BY EVA YOUKHANA AND LARISSA FÖRSTER GRAFFICITY Visual Practices and Contestations in Urban Space WILHELM FINK unter dem Förderkennzeichen 01UK0905. Die Verantwortung für den Inhalt der Veröffentlichung liegt bei den Autoren. Umschlagabbildung: © Brendon.D Bibliografische Informationen der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek: Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen National biblio grafie; detaillierte Daten sind im Internet über www.dnb.dnb.de abrufbar. Alle Rechte, auch die des auszugsweisen Nachdrucks, der fotomechanischen Wiedergabe und der Übersetzung vorbehalten. Dies betrifft auch die Verviel fältigung und Übertragung einzelner Textabschnitte, Zeichnungen oder Bilder durch alle Verfahren wie Speicherung und Übertragung auf Papier, Transpa rente, Filme, Bänder, Platten und andere Medien, soweit es nicht § 53 und 54 UrhG ausdrücklich gestatten. -

The Art Newspaper

Arab protesters put their art on the streets - The Art Newspaper Home Video News Museums Features Market Books Conservation Comment FAIRS ISSUES JOBS ARCHIVE WHAT'S ON SUBSCRIBE ADVERTISE You are not signed in | Sign in to Digital edition Tuesday 18 Sep 2012 Contemporary art Egypt Comments Arab protesters put their art on the i just would like to appreciate with a role played by streets this paper in midle east... Artists have used the walls of Cairo, Damascus and Tripoli to document the uprisings Also in News By Anny Shaw and Gareth Harris. News, Issue 231, January 2012 Four-year delay for monument to victims of Anders Published online: 30 December 2011 Breivik Sculptures by contemporary art stars fill Shanghai park Documenta ignores Kassel’s bloody history, artists say Shake up at Arp foundation Critic calls Venice Architecture Biennale “lazy" Also by Anny Shaw Monumental sculpture inspired by Cuban exodus unveiled at Hermitage A work near Tripoli airport (left) and a Ganzeer mural in Cairo Chicago’s art spaces battened down during Nato CAIRO. The Cairo-based artist Ganzeer’s stencil of Egyptian riot police, summit bravely painted on the side of the Mogamma government building on Collectors make careful choices at Art Brussels Tahrir Square last month, is the latest in a long line of works of art that Barbican Centre to expand its education partnerships have flourished in Egypt’s streets since Hosni Mubarak was ousted in February 2011. In Libya and Syria too, radical publishing and Landmark ruling to be challenged pamphleteering, street art and graffiti have thrived, even appearing in deeply conservative Saudi Arabia. -

Engaged Ephemeral Art: Street Art and the Egyptian Arab Spring

Transcultural Studies 2016.2 53 Engaged Ephemeral Art: Street Art and the Egyptian Arab Spring Saphinaz-Amal Naguib, University of Oslo “…with a box of colours costing three pounds, you draw an idea, you paint a revolution…”1 Introduction The wave of uprisings that swept over the Middle East and North Africa from December 2010 to early 2013, known as the “Arab Spring,” was what Aleida Assmann defines as an “impact event” (Assmann 2015, 44–46). I consider it a kairos, a fleeting opportune moment where time and action meet and fates may be changed. It was a promising moment, in which governments were toppled and hopes for changes were high. Not only did the Arab Spring leave its imprint on political and social life in the countries concerned, but it also marked a change in various forms of artistic expression (Hamamsy and Soliman 2013b, 12–13; 2013c, 252–254; Jondot 2013). Street art, graffiti, and calligraffiti are perhaps the most striking forms of art from this short period. Artists used to record and comment on events and developments in the political situation. They drew upon their people’s cultural memory to impart their messages and express dissent, civil disobedience, and resistance by combining images and scripts. Poetry and political songs that previously had mostly been known to underground groups and intellectual elites were widely circulated. Verses from the Tunisian poet Abul Qasim al Shabbi (1909–1934) and the Egyptian poets Fouad Negm (1929–2013) and Abdel Rahman al-Abnudi (1938–2015) were used as slogans and chanted all over the region (Nicoarea 2015; Sanders IV and Visonà 2012; Wahdan 2014).