Hill Top... a Narrative

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

All Other Huntingdon Walks

____ ....;;.;. ,)l,i.--= --...______ /H'untingdonshire D STRICT C O U N C L ALL OTHER HUNTINGDON WALKS WALKS KEY 1111 Green walks are accessible for push chairs and wheelchairs. Unless found in the Short Walks section, walks last approximately 60 minutes. 1111 Moderate walks last 30 to 60 minutes over 2 to 3 miles. Mixture of pathways and grass tracks. May include stiles or kissing gates. Not suitable for wheelchairs or buggies. 1111 Moderate walks with the option of a shorter easier route if desired. Mixture of pathways and grass tracks. May include stiles or kissing gates. Not suitable for wheelchairs or buggies. 1111 Advanced walks last 60 to 90 minutes over 3 to 4 miles. Mixture of pathways and grass tracks. May include stiles or kissing gates. Not suitable for new walkers. wheelchairs or buggies. Advanced walks with the option of a short/moderate route if desired. Mixture of pathways and grass tracks. May include stiles or kissing gates. Not suitable for wheelchairs or buggies. Abbots Ripton Meeting Point: Village Hall Car Park, Abbots Ripton, PE28 2PF Time: 60 minutes Grade: Orange Significant hazards to be aware of: Traffic when crossing a road. Route Instructions Hazard 1. Starting at the Village hall, turn left when out of the car park following the road until it meets the main road. 2. Cross over the road to take the footpath on the left-hand side. Traffic 3. Walking up to the gates (Lord De Ramsey’s estate) they will open as you approach – if not you can walk on the right-hand side. -

Incubator Building Alconbury Weald Cambridgeshire Post-Excavation

Incubator Building Alconbury Weald Cambridgeshire Post-Excavation Assessment for Buro Four on behalf of Urban & Civic CA Project: 669006 CA Report: 13385 CHER Number: 3861 June 2013 Incubator Building Alconbury Weald Cambridgeshire Post-Excavation Assessment CA Project: 669006 CA Report: 13385 CHER Number: 3861 Authors: Jeremy Mordue, Supervisor Jonathan Hart, Publications Officer Approved: Martin Watts, Head of Publications Signed: ……………………………………………………………. Issue: 01 Date: 25 June 2013 This report is confidential to the client. Cotswold Archaeology accepts no responsibility or liability to any third party to whom this report, or any part of it, is made known. Any such party relies upon this report entirely at their own risk. No part of this report may be reproduced by any means without permission. © Cotswold Archaeology Unit 4, Cromwell Business Centre, Howard Way, Newport Pagnell, Milton Keynes, MK16 9QS t. 01908 218320 e. [email protected] 1 Incubator Building, Alconbury Weald, Cambridgeshire: Post-Excavation Assessment © Cotswold Archaeology CONTENTS SUMMARY ..................................................................................................................... 4 1 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................ 5 2 AIMS AND OBJECTIVES ................................................................................... 6 3 METHODOLOGY ............................................................................................... 6 4 RESULTS ......................................................................................................... -

GUIDE £675,000 SUDBROOK HOUSE FARM BARNS, Ancaster

SUDBROOK HOUSE FARM BARNS , Ancaster , Grantham, GUIDE £ 675 ,000 County Sudbrook House Farm Barns, Ancaster, PLANNING TENURE AND POSSESSION Grantham, Lincolnshire, NG32 3RJ, Planning Permission and Listed Building Consent were granted by The Property is freehold and vacant possession will be given upon South Kesteven District Council on 25 November 2016. The completion. Planning Permission (S16/1776) is for the demolition of barn, plant building and portal unit and conversion and extension of VALUE ADDED TAX barns to create 6no. dwellings. The Listed Building Consent Should any sale of the Property , or any right attached to it become (S16/1844) is for internal and external alterations to range of a chargeable supply for the purpose of VAT, such tax shall be barns, including demolition of lean-to structures in relation to payable by the Buyer in addition to the contract price. residential conversion. Copies of the Planning Permission and Listed Building Consent are available by email on request. DISPUTES Should any dispute arise as to the boundaries or any point arising DESCRIPTION in these Particulars, schedule, plan or interpretation of any of The four units comprise: them the question shall be referred to the arbitration of the Selling Agent, whose decision acting as expe rt shall be final. The Buyer Unit 1 ––– Field View ,,, a mainly stone and slate barn with attached shall be deemed to have full knowledge of all boundaries and cart shed. neither the Seller nor the Seller’s Agents will be responsible for defining the boundaries or the ownership thereof. Unit 4 ––– The Granary , a three storey stone and pantile waggon shed with granary over and remains of a single storey wing. -

Warehousing Complex Ermine Street, Barkston Heath Grantham, Ng32 3Qg

brown-co.com WAREHOUSING COMPLEX ERMINE STREET, BARKSTON HEATH GRANTHAM, NG32 3QG FOR SALE / TO LET • 6 detached high-bay warehouses with a Gross Internal Area totaling approximately 225,324 square feet (20,933 square metres) • Total site area approximately 21 acres (8.50 hectares) • Located fronting the B6403 Ermine Street approximately 6 miles north of Grantham and 11 miles north of the A1 at Colsterworth • Suitable for all B8 warehousing and bulk storage uses PRICE £3,650,000 FREEHOLD RENT £400,000 P.A.X LEASEHOLD Granta Hall, 6 Finkin Street, Grantham, Lincolnshire, NG31 6QZ Tel 01475 514433 Fax 01476 594242 Email [email protected] Ermine Street, Barkston Heath ACCOMMODATION (all figures approx.) Subject to Contract In terms of Gross Internal Area the warehouses have the following LOCATION approximate areas: The warehouse complex is situated directly opposite RAF Barkston Heath with an Description Sq Ft Sq M extensive frontage to the B6403 Ermine Street Warehouse 1 27,317 2,538 which is located approximately 6 miles north Warehouse 2 27,275 2,534 of the town of Grantham and approximately Warehouse 3 27,373 2,543 11 miles north of the A1 at Colsterworth. Warehouse 4 27,357 2,542 The location offers excellent road links to the Warehouse 5 57,942 5,383 regional road network. Grantham is a large Warehouse 6 58,060 5,394 town located approximately 110 miles north of London, 20 miles east of Nottingham and Warehouses 1-4 comprise the older 25 miles south of Lincoln. The A1 runs accommodation with Warehouses 5 and 6 adjacent to the town and main line rail being those constructed circa 1990. -

Alconbury Map Oct2015

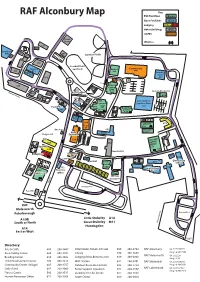

RAF Alconbury Map Key FSS Facilities Green Base Facilities Blue Lodging Yellow Red Other Buildings Gray AAFES Orange Thrift Store Wireless 511 P 510 Fire Dept 490 566 501 567 Baseball Fields 491 Michigan California 564 548 Football Field Finance and Track Lemon Commissary 558 Kansas 516 Lot 648 TMO Recycling 561 Center 562 613 Gas 596 P Start 560 Fitness Center P GYM 595 Auto Hobby Center Base perimeter Base Theater 586 539 498 Iowa 301 626 499 592 Chapel P ODR 423rd Medical P Community Squadron Clinic Arts P Center 623 P Post Ofce Arizona and 685 Crafts Bowling 502 Alabama Daily Grind Center P 616 Texas P P Bank Arizona CU/ 582 ATM P 594 Library 675 Food 678 CT Bus Stop 652 Education Utah Base Dorm Center Playground Exchange P P TLF 584 FSS/VAT/ 628 657 A&FRC/ DEERS/ P VQ/DVQ CSS 640 699 671 Teen Center Spruce Drive Reception Shoppette 639 585 Colorado Colorado 677 682 Launderette 660 Birch Drive P Elementary 570 Mini Mall Youth Elementary P 693 School Center 6401 6402 572 6403 680 694 P 6404 High School Housing 6405 691 637 6406 691 Ofce 6407 Stukeley Inn 6408 700 Birch Drive 6409 Child 6410 CDC Development Bravo Cedar Drive Texas Elm Drive Housing Area Delta Lane Elm Drive Pass Ofce Cedar Drive Gate Foxtrot Lane Maple Drive RAF Molesworth Oak Drive Peterborough Housing Area A1(M) Little Stukeley A14 South or North Great Stukeley M11 Base perimeter Huntingdon A14 East or West India Lane Emergency Gate Directory: Arts & Crafts 685 268-3867 Information, Tickets & Travel 685 268-3704 RAF Alconbury lat: 52.3636936 Auto Hobby Center 626 -

The Castor Roman Trail Guide

The Castor Roman Walk Welcome to the ‘Route Plan’ and teachers notes for the Castor Roman Walk. The walk is approximately 3km, with an optional extension of 0.7km. We suggest that you bring with you OS Explorer 227. The start point is at grid reference TL 124984 This is very largely a walk of the imagination, but what imagination! Roman Emperors travelled across the fields that you will cross; Roman Legions tramped the roads you will stand on, heading to Hadrian’s Wall; In the fields where wheat now grows, potters made Castorware that was extensively traded across the province. (and further afield?) The large Roman building, or Praetorium, where St Kyneburgha’s Church now stands was as big as Peterborough Cathedral And near to where you walk the oldest known Christian silverware in the Roman Empire (now in the British Museum) was found. But you will need your imagination and a sharp eye for the evidence in the landscape to tell the story, as the evidence of Roman occupation of the area is very largely buried. 1 Starting the Walk The walk starts where Church Walk meets Peterborough Road, at the corner of the school playing field. Turn right and walk down Peterborough Road, past the Village Hall and take the first left into Port Lane opposite the Prince of Wales Feathers. Go down Port Lane and stop when you have passed the right angle bends after the houses. 1. Berrystead Manor On the right, at the far side of the field, is the site of Berrystead Manor, which was occupied from the Saxon period onwards, and is one of the earliest known post-Roman settlements in the area. -

Bespoke Business Space Available Enterprisealconbury Campus HCV Entrance HCV

For further information on the opportunities BESPOKE BUILDINGS available, contact one of the joint agents: Bespoke business Barker Storey Savills Matthews space available Alan Matthews William Rose [email protected] [email protected] Alconbury Enterprise Campus Richard Adam Phil Ridoutt [email protected] [email protected] savills.co.uk 01223 347 000 01733 344 414 9 acre parcel HCV entrance To let or for sale 9 acre (3.65ha) parcel, high quality business space available for: ● B1: Research & Development and Urban&Civic give notice that: 1 These particulars do not form part of any offer or contract Light Industrial and must not be relied upon as statements or representations of fact. ● B2: Industrial 2 Any areas, measurements or distances are approximate and The Club, The Boulevard subject to final measurement. The text, photographs and plans From 40,000 sq ft to 220,000 sq ft (3,716 sq m Alconbury Enterprise Campus are for guidance only and are not necessarily comprehensive. It should not be assumed that the site has all the necessary to 20,438 sq m) Alconbury Weald, Huntingdon planning, building regulation or other consents and Urban&Civic Cambridgeshire PE28 4XA has not tested any services, equipment or facilities. Purchasers must satisfy themselves by inspection or otherwise. Figures Buildings designed to your business’ needs T: 01480 413 141 quoted in these particulars may be subject to VAT in addition. alconbury-weald.co.uk July 2019 alconbury-weald.co.uk Opportunity, location, connections Alconbury Enterprise Campus lies at the heart of the high-quality, mixed-use development of Alconbury Weald. -

NCA Profile 47 Southern Lincolnshire Edge

National Character 47. Southern Lincolnshire Edge Area profile: Supporting documents www.naturalengland.org.uk 1 National Character 47. Southern Lincolnshire Edge Area profile: Supporting documents Introduction National Character Areas map As part of Natural England’s responsibilities as set out in the Natural Environment White Paper,1 Biodiversity 20202 and the European Landscape Convention,3 we are revising profiles for England’s 159 National Character Areas North (NCAs). These are areas that share similar landscape characteristics, and which East follow natural lines in the landscape rather than administrative boundaries, making them a good decision-making framework for the natural environment. Yorkshire & The North Humber NCA profiles are guidance documents which can help communities to inform West their decision-making about the places that they live in and care for. The information they contain will support the planning of conservation initiatives at a East landscape scale, inform the delivery of Nature Improvement Areas and encourage Midlands broader partnership working through Local Nature Partnerships. The profiles will West also help to inform choices about how land is managed and can change. Midlands East of Each profile includes a description of the natural and cultural features England that shape our landscapes, how the landscape has changed over time, the current key drivers for ongoing change, and a broad analysis of each London area’s characteristics and ecosystem services. Statements of Environmental South East Opportunity (SEOs) are suggested, which draw on this integrated information. South West The SEOs offer guidance on the critical issues, which could help to achieve sustainable growth and a more secure environmental future. -

The Transport System of Medieval England and Wales

THE TRANSPORT SYSTEM OF MEDIEVAL ENGLAND AND WALES - A GEOGRAPHICAL SYNTHESIS by James Frederick Edwards M.Sc., Dip.Eng.,C.Eng.,M.I.Mech.E., LRCATS A Thesis presented for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Salford Department of Geography 1987 1. CONTENTS Page, List of Tables iv List of Figures A Note on References Acknowledgements ix Abstract xi PART ONE INTRODUCTION 1 Chapter One: Setting Out 2 Chapter Two: Previous Research 11 PART TWO THE MEDIEVAL ROAD NETWORK 28 Introduction 29 Chapter Three: Cartographic Evidence 31 Chapter Four: The Evidence of Royal Itineraries 47 Chapter Five: Premonstratensian Itineraries from 62 Titchfield Abbey Chapter Six: The Significance of the Titchfield 74 Abbey Itineraries Chapter Seven: Some Further Evidence 89 Chapter Eight: The Basic Medieval Road Network 99 Conclusions 11? Page PART THREE THr NAVIGABLE MEDIEVAL WATERWAYS 115 Introduction 116 Chapter Hine: The Rivers of Horth-Fastern England 122 Chapter Ten: The Rivers of Yorkshire 142 Chapter Eleven: The Trent and the other Rivers of 180 Central Eastern England Chapter Twelve: The Rivers of the Fens 212 Chapter Thirteen: The Rivers of the Coast of East Anglia 238 Chapter Fourteen: The River Thames and Its Tributaries 265 Chapter Fifteen: The Rivers of the South Coast of England 298 Chapter Sixteen: The Rivers of South-Western England 315 Chapter Seventeen: The River Severn and Its Tributaries 330 Chapter Eighteen: The Rivers of Wales 348 Chapter Nineteen: The Rivers of North-Western England 362 Chapter Twenty: The Navigable Rivers of -

Hill Top, Alconbury Weston 2020 Sawtry History Society Excavation Site Diary Summary

HILL TOP, ALCONBURY WESTON 2020 SAWTRY HISTORY SOCIETY EXCAVATION SITE DIARY SUMMARY Site Details Site Reference Code: ALW171-20 Location: NGR TL1877 (OS. Explorer Map 225. Huntingdon and St Ives - West) Site Bench Mark (SBM): Description – South corner of tree line bordering residential gardens. Lat and Long – 52°23'2.03"N, 0°15'43.89"W (Google Earth 2018) NGR – TL18374 77628 (OS. Explorer Map 225. Huntingdon and St Ives - West) AMSL – m (Mapping) Figure 0.1: Montage of pre-Season 3 images Aims and Objectives Investigate the pit revealed in the south end of Trench #1 in order to: - determine its form and use(s) - excavate the fill of the pit for 100 percent environmental sampling in order to further understand the pit's use(s) Investigate the possible wall and post-hole in close proximity to the pit in order to determine whether they are indeed structural and to further determine whether the post-hole respects a supporting post or a door post. Investigate the marked differences immediately south of the pit and possible structural features; marked differences include soil type, colour and texture, and the absence of CBM, tesserae and other archaeological artefacts. Conduct geophysical earth resistance survey. Project: Romano-British Settlement on Hill Top Season: 03 This session of excavation and geophysical survey proved to be another successful set of investigations that, despite the weather and ground conditions, addressed all the aims and objectives set above. The true extent of the pit was revealed and the half section showed it to be a 'beehive' or 'bell' shaped pit; a style of in-ground storage pit in common use from the Late Iron Age through the second century Romano-British - as evinced by finds from the pit fill. -

Land at Ermine St, Former AC Williams Garage Site Ancaster, Lincs

01977 681885 Prospect House [email protected] Garden Lane Sherburn-in-Elmet Leeds North Yorkshire LS25 6AT Land at Ermine St, Former AC Williams Garage Site Ancaster, Lincs. Archaeological Assessment Local Planning Authority: South Kesteven District Council Planning Reference: N/a NGR: SK 984 445 Date of Report: July 2014 Author: Naomi Field Report No.: LPA-60 Prospect Archaeology Ltd 25 West Parade Lincoln LN1 1NW www.prospectarc.com Registered Office Prospect House, Garden Lane, Sherburn-in-Elmet, Leeds, LS25 6AT Land at Ermine St, Ancaster, Lincs Archaeological Assessment CONTENTS PLANNING SUMMARY ....................................................................................................................................III 1.0 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ......................................................................................................................... 3 1.0 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................... 2 2.0 SITE DESCRIPTION ................................................................................................................................ 2 3.0 STATUTORY AND PLANNING POLICY CONTEXT .................................................................................... 2 4.0 ASSESSMENT METHODOLOGY AND SIGNIFICANCE CRITERIA ............................................................... 4 5.0 BASELINE CONDITIONS ....................................................................................................................... -

Roman Roads of Britain

Roman Roads of Britain A Wikipedia Compilation by Michael A. Linton PDF generated using the open source mwlib toolkit. See http://code.pediapress.com/ for more information. PDF generated at: Thu, 04 Jul 2013 02:32:02 UTC Contents Articles Roman roads in Britain 1 Ackling Dyke 9 Akeman Street 10 Cade's Road 11 Dere Street 13 Devil's Causeway 17 Ermin Street 20 Ermine Street 21 Fen Causeway 23 Fosse Way 24 Icknield Street 27 King Street (Roman road) 33 Military Way (Hadrian's Wall) 36 Peddars Way 37 Portway 39 Pye Road 40 Stane Street (Chichester) 41 Stane Street (Colchester) 46 Stanegate 48 Watling Street 51 Via Devana 56 Wade's Causeway 57 References Article Sources and Contributors 59 Image Sources, Licenses and Contributors 61 Article Licenses License 63 Roman roads in Britain 1 Roman roads in Britain Roman roads, together with Roman aqueducts and the vast standing Roman army, constituted the three most impressive features of the Roman Empire. In Britain, as in their other provinces, the Romans constructed a comprehensive network of paved trunk roads (i.e. surfaced highways) during their nearly four centuries of occupation (43 - 410 AD). This article focuses on the ca. 2,000 mi (3,200 km) of Roman roads in Britain shown on the Ordnance Survey's Map of Roman Britain.[1] This contains the most accurate and up-to-date layout of certain and probable routes that is readily available to the general public. The pre-Roman Britons used mostly unpaved trackways for their communications, including very ancient ones running along elevated ridges of hills, such as the South Downs Way, now a public long-distance footpath.