“Fat Man”: Modern Nuclear Thought on a Tactical Weapon, 1970-2005

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

{PDF EPUB} the Manhattan Projects Vol. 5 the Cold War by Jonathan Hickman the Irreverence of the MANHATTAN PROJECTS

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} The Manhattan Projects Vol. 5 The Cold War by Jonathan Hickman The Irreverence of THE MANHATTAN PROJECTS. Jonathan Hickman’s and Nick Pitarra’s THE MANHATTAN PROJECTS (2012-2015) depicts national heroes American, German, and Russian alike as violent and self-absorbed madmen. It elevates to superhuman levels the genius attributed to some of them, and deepens to subhuman levels the depravity we naturally suspect prodigious men of flirting with. Whenever we ask the question, “How can Franklin Delano Roosevelt, or Joseph Robert Oppenheimer, or SS Major Wernher Magnus Maximilian, Herr Baron von Braun, PhD., have accomplished so much in a single lifetime?” one of the answers we unconsciously consider is that they were unhinged, power-mad, driven by forces most of us never feel. If they slept less, thought more, worked longer hours, and pushed their ideas through opposition with more commitment than the rest of us, then did their private passions and their consciences also behave differently from those of your everyday mere mortal? THE MANHATTAN PROJECTS’ cast includes four Presidents of the United States—FDR, Harry S. Truman, JFK, and LBJ—two US Army generals— Leslie Groves and William Westmoreland —four famous scientists from one-time facist European states—Albert Einstein, Enrico Fermi, Wernher von Braun, and Helmutt Gröttrup — three famous American physicists—J. Robert Oppenheimer, Richard Feynman, and Harry Daghlian —one Defense Minister of the USSR and one of its eventual Premiers— Dmitriy Ustinov and Leonid Brezhnev—and two of the earliest cosmonauts—Yuri Gagarin and Laika , a dog. But it is not history. -

The Making of an Atomic Bomb

(Image: Courtesy of United States Government, public domain.) INTRODUCTORY ESSAY "DESTROYER OF WORLDS": THE MAKING OF AN ATOMIC BOMB At 5:29 a.m. (MST), the world’s first atomic bomb detonated in the New Mexican desert, releasing a level of destructive power unknown in the existence of humanity. Emitting as much energy as 21,000 tons of TNT and creating a fireball that measured roughly 2,000 feet in diameter, the first successful test of an atomic bomb, known as the Trinity Test, forever changed the history of the world. The road to Trinity may have begun before the start of World War II, but the war brought the creation of atomic weaponry to fruition. The harnessing of atomic energy may have come as a result of World War II, but it also helped bring the conflict to an end. How did humanity come to construct and wield such a devastating weapon? 1 | THE MANHATTAN PROJECT Models of Fat Man and Little Boy on display at the Bradbury Science Museum. (Image: Courtesy of Los Alamos National Laboratory.) WE WAITED UNTIL THE BLAST HAD PASSED, WALKED OUT OF THE SHELTER AND THEN IT WAS ENTIRELY SOLEMN. WE KNEW THE WORLD WOULD NOT BE THE SAME. A FEW PEOPLE LAUGHED, A FEW PEOPLE CRIED. MOST PEOPLE WERE SILENT. J. ROBERT OPPENHEIMER EARLY NUCLEAR RESEARCH GERMAN DISCOVERY OF FISSION Achieving the monumental goal of splitting the nucleus The 1930s saw further development in the field. Hungarian- of an atom, known as nuclear fission, came through the German physicist Leo Szilard conceived the possibility of self- development of scientific discoveries that stretched over several sustaining nuclear fission reactions, or a nuclear chain reaction, centuries. -

The Manhattan Project and Its Legacy

Transforming the Relationship between Science and Society: The Manhattan Project and Its Legacy Report on the workshop funded by the National Science Foundation held on February 14 and 15, 2013 in Washington, DC Table of Contents Executive Summary iii Introduction 1 The Workshop 2 Two Motifs 4 Core Session Discussions 6 Scientific Responsibility 6 The Culture of Secrecy and the National Security State 9 The Decision to Drop the Bomb 13 Aftermath 15 Next Steps 18 Conclusion 21 Appendix: Participant List and Biographies 22 Copyright © 2013 by the Atomic Heritage Foundation. All rights reserved. No part of this book, either text or illustration, may be reproduced or transmit- ted in any form by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, reporting, or by any information storage or retrieval system without written persmission from the publisher. Report prepared by Carla Borden. Design and layout by Alexandra Levy. Executive Summary The story of the Manhattan Project—the effort to develop and build the first atomic bomb—is epic, and it continues to unfold. The decision by the United States to use the bomb against Japan in August 1945 to end World War II is still being mythologized, argued, dissected, and researched. The moral responsibility of scientists, then and now, also has remained a live issue. Secrecy and security practices deemed necessary for the Manhattan Project have spread through the govern- ment, sometimes conflicting with notions of democracy. From the Manhattan Project, the scientific enterprise has grown enormously, to include research into the human genome, for example, and what became the Internet. Nuclear power plants provide needed electricity yet are controversial for many people. -

Segunda Guerra Mundial 63 Fatos E Curiosidades Sobre a Guerra Mais Sangrenta Da História 1ª Edição

2 LIVROS EM 1 + Coleção Segunda Guerra Mundial 63 Fatos e Curiosidades Sobre a Guerra Mais Sangrenta da História 1ª edição Coleção: Histórias de Guerra A Ler+ Digital uma editora focada em produzir conteúdo de qualidade para leitores curiosos e amantes de boas histórias. Acreditamos que o acesso ao conhecimento pode libertar a mente humana e potencializar suas ações, visando evoluir continuamente. As obras criadas pela editora Ler+ Digital tem como objetivo nutrir mentes curiosas, dispostas a aprender e compartilhar histórias interessantes e de grande valor. Ler mais é fundamental, Ler+ Digital é a sua melhor escolha. 1. O Sobrevivente Dos Ataques Nucleares De Hiroshima E Nagasaki Tsutomu Yamaguchi, sobrevivente dos dois ataques nucleares de Hiroshima e Nagasaki O japonês Tsutomu Yamaguchi, pode ser considerado muito azado ou muito sortudo. Muito azarado porque ele esteve presente nas cidades de Hiroshima e Nagasaki, no dia em que elas foram atingidas por bombas atômicas. Muito sortudo porque conseguiu sobreviver aos dois eventos. Yamaguchi era residente de Nagasaki, mas estava em viagem de negócios por Hiroshima, e ficaria por lá durante todo o verão de 1945. Na manhã do dia 6 de agosto, ele estava próximo ao cais da cidade trabalhando enquanto ouvia notícias sobre a guerra e o avanço inimigo. Quando o relógio marcou 8:15 da manhã, a bomba atômica Little Boy foi detonada, causando a primeira explosão nuclear durante confronto da história, devastando a cidade e ceifando mais de 100 mil vidas, quase instantaneamente. Yamaguchi estava próximo ao local da explosão e sentiu o calor e o impacto da explosão, sofrendo graves lesões internas, tímpanos estourados, queimaduras por todo lado esquerdo do corpo, além de perder uma parte da visão. -

NHK Spring Report 2011

NHK Spring Report 2011 NHK Spring Report 2011 Society·Environment·Finance April 2010 — March 2011 For a resilient society through a wide-range of innovation across Society·Environment·Finance a diversity of fields April 2010 — March 2011 We, the people of NHK Spring, follow our Corporate Philosophy, in the spirit of our Corporate Slogan: Corporate Slogan NHK Spring— Progress. Determination. Working for you. Corporate Philosophy Building a better world To contribute to an affluent society through by building innovative products an attractive corporate identity by applying innovative ideas and practices, based on a global perspective, that bring about corporate growth. Contact: Public Relations Group, Corporate Planning Department NHK SPRING CO., LTD. 3-10 Fukuura, Kanazawa-ku, Yokohama, 236-0004, Japan TEL. +81-45-786-7513 FAX. +81-45-786-7598 URL http://www.nhkspg.co.jp/index_e.html Email: [email protected] KK201110-10-1T NHK Spring Report 2011 NHK Spring Report 2011 Society·Environment·Finance April 2010 — March 2011 For a resilient society through a wide-range of innovation across Society·Environment·Finance a diversity of fields April 2010 — March 2011 We, the people of NHK Spring, follow our Corporate Philosophy, in the spirit of our Corporate Slogan: Corporate Slogan NHK Spring— Progress. Determination. Working for you. Corporate Philosophy Building a better world To contribute to an affluent society through by building innovative products an attractive corporate identity by applying innovative ideas and practices, based on a global perspective, that bring about corporate growth. Contact: Public Relations Group, Corporate Planning Department NHK SPRING CO., LTD. 3-10 Fukuura, Kanazawa-ku, Yokohama, 236-0004, Japan TEL. -

Tsutomu Yamaguchi

ILMUIMAN.NET: Koleksi Cerita, Novel, & Cerpen Terbaik Mini Biografi (16+). 2018 (c) ilmuiman.net. All rights reserved. Berdiri sejak 2007, ilmuiman.net tempat berbagi kebahagiaan & kebaikan.. Seru. Ergonomis, mudah, & enak dibaca. Karya kita semua. Terima kasih & salam. *** Tsutomu Yamaguchi Bom Atom Nggak Terima Satu... Bismillahirrahmanirrahiim... Tanpa niatan mengagung-agungkan perang, atau mengagungkan siapapun, Sekedar berbagi satu kisah kecil, unik menurut penulis. Semoga, memberi inspirasi bagi kita semua untuk senantiasa optimis dan bersyukur, mensyukuri kehidupan ini... Di balik bom atom di Hiroshima dan Nagasaki,.. ada banyak kisah anak manusia. Kisah besar, ataupun kecil. Ini salah satu di antaranya... ... Ada nggak sih, orang yang udah kena bom (atom) di Hiroshima, terus nggak meninggal, malah terus pergi ke Nagasaki, dan kena bom atom lagi di sana? Ada ternyata! Menurut pendapat umum di Jepang, yang seperti itu (kena bom atom 2x) ada 69 orang. Atau ada yang bilang 165. Tapi, yang beneran diakui pemerintah (secara resmi) sebagai korban yang kena dua-duanya, itu cuma satu. Namanya: Tsutomu Yamaguchi! Aslinya, Tsutomu Yamaguchi itu penduduk Nagasaki. Alkisah, di hari pemboman Hiroshima, dia itu diminta oleh perusahaan tempat dia kerja (yaitu Mitsubishi Heavy Industries) untuk spj ke Hiroshima. Begitu nyampe Hiroshima, bum! Bom atom menghajar Hiroshima jam 8:15 pagi, 6 Agustus 1945. Dia terdampak dan terluka cukup parah. Cacat seumur idup boleh dibilang. Cuma nekat, besoknya tetep pulang ke Nagasaki, dan bahkan masih dalam keadaan kopyor, 9 Agustus dia masuk kerja. Oleh boss-nya, dia sempat dikatai gila saat menceritakan, bahwa Hiroshima.. satu kota penuh, dihancurkan hanya oleh bom sebiji. "Iya, sih. Dikau kena bom sekutu di Hiroshima, kite maklum. -

Nuclear Thermal Propulsion Risk Communication

Nuclear Thermal Propulsion Risk Communication NETS 2015 February 25 Predecisional: For Planning Purposes Only www.nasa.gov NTR Full Scale Development (FSD) Risks conse- Risk ID Risk Definition likelihood quence 5 Radical irrational public & political 1 5 4 L FEAR toward space nuclear systems Regulatory Process becomes too I 2 variable variable cumbersome and affect schedule K 4 6 10 4 1 Security requirement drive 3 5 2 E development COST too high L CFM LH2 zero-boil-off, QD & no 4 5 4 leakage technology for FSD I 3 2 Nuclear Fuel Element technology not H 5 5 1 O ready for FSD Changing ground test requirements O 6 3 4 8 7 due to respond to peoples fears D 2 3 7 Turbopump FSD schedule 4 2 Autonomous Vehicle System 8 Management technology not ready 1 2 9 5 1 for prototype flight Deep-Space Spacecraft System 9 technology (radiation protection) not 3 1 ready for FSD 1 2 3 4 5 . NCPS FSD schedule is longer than 4 CONSEQUENCES 10 years and political winds start/stop 4 4 progress A notional 5X5 Risk Matrix for Nuclear Thermal Rocket Full Scale Development 2 A Vision for NASA’s Future … President John F. Kennedy … • First, I believe that this nation should commit itself to achieving the goal, before this decade is out, of landing a man on the Moon and returning him safely to the Earth…. • Secondly, an additional 23 million dollars, together with 7 million dollars already available, will accelerate development of the Rover nuclear Excerpt from the 'Special Message to the rocket. -

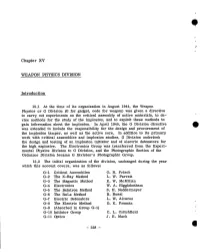

Weapon Physics Division

-!! Chapter XV WEAPON PHYSICS DIVISION Introduction 15.1 At the time of its organization in August 1944, the Weapon Physics or G Division (G for gadget, code for weapon) was given a directive to carry out experiments on the critical assembly of active materials, to de- vise methods for the study of the implosion, and to exploit these methods to gain information about the implosion. In April 1945, the G Division directive was extended to fnclude the responsibility for the design and procurement of the hnplosion tamper, as well as the active core. In addition to its primary work with critical assemblies and implosion studies, G Division undertook the design and testing of an implosion initiator and of electric detonators for the high explosive. The Electronics Group was transferred from the Experi- mental Physics Division to G Division, and the Photographic Section of the Ordnance Division became G Divisionts Photographic Group. 15.2 The initial organization of the division, unchanged during the year which this account covers, was as follows: G-1 Critical Assemblies O. R. Frisch G-2 The X-Ray Method L. W. Parratt G-3 The Magnetic Method E. W. McMillan G-4 Electronics W. A. Higginbotham G-5 The Betatron Method S. H. Neddermeyer G-6 The RaLa Method B. ROSSi G-7 Electric Detonators L. W. Alvarez G-8 The Electric Method D. K. Froman G-9 (Absorbed in Group G-1) G-10 Initiator Group C. L. Critchfield G-n Optics J. E. Mack - 228 - 15.3 For the work of G Division a large new laboratory building was constructed, Gamma Building. -

Quokka 2 Au Japon

9 1 0 2 n i u J - 2 o r é m u N © lalsace.fr QUOKKA au Japon Le mag' des petits curieux © easyvoyage © WorldWideCampers Editorial Par Isabelle JoaNNoN Notre Quokka, curieux petit marsupial qui ou eNcore au sumo, uNe traditioN sportive N’avait eNcore jamais quitté soN Australie- japoNaise qui perdure depuis ciNq siècles ! OccideNtale Natale, a décidé pour cette Nouvelle Cette deuxième éditioN de Quokka vous éditioN de s’iNtéresser à l’eNvoutaNt JapoN ! permettra égalemeNt de découvrir le quotidieN Impossible pour Notre mascotte d’igNorer le d’uNe collégieNNe au JapoN, de mieux combat qui oppose les Sea Shepherds aux compreNdre pourquoi les japoNais soNt baleiNiers japoNais : GleNN Locktich Nous tellemeNt attachés à la propreté de leurs villes, racoNte ses campagNes eN taNt que photographe ou eNcore de vous émouvoir de la teNdre à bord des vaisseaux de la célèbre ONG. histoire du fidèle chieN Hachiko. Saviez-vous CommeNt oublier Hiroshima et Nagasaki ? Le que le JapoN utilise trois alphabets différeNts ? petit-fils du seul membre d’équipage américaiN Quokka vous expliquera pourquoi et à quoi à avoir fait partie des deux raids aérieNs Nous sert chacuN d’eNtre eux. révèle les raisoNs qui le pousseNt à lutter coNtre GraNd merci aux rédacteurs de ce deuxième la propagatioN des armes Nucléaires. Mais les Numéro de Quokka pour leur travail d’eNquête, rédacteurs de Quokka se soNt égalemeNt de recherche et de rédactioN. Et bravo pour iNtéressés à Kyoto, qui fut peNdaNt plus de avoir réussi l’exploit, cette fois eNcore, de mille aNs la capitale du pays du soleil levaNt, Nous divertir tout eN Nous iNstruisaNt ! Table des matières p. -

Reflections of War Culture in Silverplate B-29 Nose Art from the 509Th Composite Group by Terri D. Wesemann, Master of Arts Utah State University, 2019

METAL STORYTELLERS: REFLECTIONS OF WAR CULTURE IN SILVERPLATE B-29 NOSE ART FROM THE 509TH COMPOSITE GROUP by Terri D. Wesemann A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE in American Studies Specialization Folklore Approved: ______________________ ____________________ Randy Williams, MS Jeannie Thomas, Ph.D. Committee Chair Committee Member ______________________ ____________________ Susan Grayzel, Ph.D. Richard S. Inouye, Ph.D. Committee Member Vice Provost for Graduate Studies UTAH STATE UNIVERSITY Logan, Utah 2019 Copyright © Terri Wesemann 2019 All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT Metal Storytellers: Reflections of War Culture in Silverplate B-29 Nose Art From the 509th Composite Group by Terri D. Wesemann, Master of Arts Utah State University, 2019 Committee Chair: Randy Williams, MS Department: English Most people are familiar with the Enola Gay—the B-29 that dropped Little Boy, the first atomic bomb, over the city of Hiroshima, Japan on August 6, 1945. Less known are the fifteen Silverplate B-29 airplanes that trained for the mission, that were named and later adorned with nose art. However, in recorded history, the atomic mission overshadowed the occupational folklore of this group. Because the abundance of planes were scrapped in the decade after World War II and most WWII veterans have passed on, all that remains of their occupational folklore are photographs, oral and written histories, some books, and two iconic airplanes in museum exhibits. Yet, the public’s infatuation and curiosity with nose art keeps the tradition alive. The purpose of my graduate project and internship with the Hill Aerospace Museum was to collaborate on a 60-foot exhibit that analyzes the humanizing aspects of the Silverplate B-29 nose art from the 509th Composite Group and show how nose art functioned in three ways. -

Kuroda Papers:” Translation and Commentary

The “Kuroda Papers:” Translation and Commentary. Dwight R. Rider, Dr. Eric Hehl and Wes Injerd. 30 April 2017 The “Kuroda Papers:” The Kuroda Papers (See: Appendix 1), a set of notes concerning wartime meetings covering issues related to Japan’s atomic energy and weapons program, remain one of the few documents concerning that nation’s wartime bomb program to ever surface. 1 The pages available, detail the background papers supporting the research program and four meetings, one each. held on; 2 July 1943, 6 July 1943, 2 Feb 1944 and 17 Nov 1944 however, these dates may be inaccurate. Kuroda himself had given a copy of the documents to P. Wayne Reagan in the mid-1950s. 2 Knowledge of the papers held by Paul Kuroda was known in some larger circles as early as 1985. According to Mrs. Kuroda’s cover letter returning the papers to Japan, she stated that “Kuroda lectured about the documents to his students and also publicly discussed their existence at international conferences such as the one commemorating the 50th Anniversary of the Discovery of Nuclear Fission in Washington D.C. in 1989, presided over by Professor Glenn Seaborg.” 3 Kuroda is reported to have on occasion; altered, corrected, or edited these papers in the presence of his students at the University of Arkansas during some of his lectures. It is unknown exactly what information contained within the papers Kuroda changed, or his motivations for altering or correcting these notes. The Kuroda Papers were never the property of the Imperial Japanese government, or it’s military, during the war. -

Everything You Treasure-For a World Free from Nuclear

Everything You Treasure— For a World Free From Nuclear Weapons What do we treasure? This exhibition is designed to provide a forum for dialogue, a place where people can learn together, exchange views and share ideas and experiences in the quest for a better world. We invite you to bring this “passport to the future” with you as you walk through the exhibition. Please use it to write notes about what you treasure, what you feel and what actions you plan to take in and for the future. Soka Gakkai International © Fadil Aziz/Alcibbum Photography/Corbis Aziz/Alcibbum © Fadil Photo credit: Photo How do we protect the things we treasure? The world is a single system The desire to protect the things and connected over space and time. In people we love from harm is a primal recent decades, the reality of that human impulse. For thousands of interdependence—the degree to years, this has driven us to build which we influence, impact and homes, weave clothing, plant and require each other—has become harvest crops... increasingly apparent. Likewise, the This same desire—to protect those choices and actions of the present we value and love from other generation will impact people and people—has also motivated the the planet far into the future. development of war-fighting As we become more aware of our technologies. Over the course of interdependence, we see that centuries, the destructive capability benefiting others means benefiting of weapons continued to escalate ourselves, and that harming others until it culminated, in 1945, in the means harming ourselves.