North American Native Plant Society

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Developmental and Genetic Bases of Apetaly in Bocconia Frutescens

Arango‑Ocampo et al. EvoDevo (2016) 7:16 DOI 10.1186/s13227-016-0054-6 EvoDevo RESEARCH Open Access The developmental and genetic bases of apetaly in Bocconia frutescens (Chelidonieae: Papaveraceae) Cristina Arango‑Ocampo1, Favio González2, Juan Fernando Alzate3 and Natalia Pabón‑Mora1* Abstract Background: Bocconia and Macleaya are the only genera of the poppy family (Papaveraceae) lacking petals; how‑ ever, the developmental and genetic processes underlying such evolutionary shift have not yet been studied. Results: We studied floral development in two species of petal-less poppies Bocconia frutescens and Macleaya cordata as well as in the closely related petal-bearing Stylophorum diphyllum. We generated a floral transcriptome of B. frutescens to identify MADS-box ABCE floral organ identity genes expressed during early floral development. We performed phylogenetic analyses of these genes across Ranunculales as well as RT-PCR and qRT-PCR to assess loci- specific expression patterns. We found that petal-to-stamen homeosis in petal-less poppies occurs through distinct developmental pathways. Transcriptomic analyses of B. frutescens floral buds showed that homologs of all MADS-box genes are expressed except for the APETALA3-3 ortholog. Species-specific duplications of other ABCE genes inB. frute- scens have resulted in functional copies with expanded expression patterns than those predicted by the model. Conclusions: Petal loss in B. frutescens is likely associated with the lack of expression of AP3-3 and an expanded expression of AGAMOUS. The genetic basis of petal identity is conserved in Ranunculaceae and Papaveraceae although they have different number of AP3 paralogs and exhibit dissimilar floral groundplans. -

Shade Monthly July 2016

Shade Monthly July 2016 We need more articles. Please do write something for us and send it to [email protected] (1) Plant of the Month. Cardiocrinum giganteum Yes, I know it is monocarpic slug bait, but with a little effort and about six years you can build up a population of these stately beauties. Growing up to 8 ft tall and topped by huge,sweet-smelling, trumpet shaped flowers they brighten up the shade in June. All they ask for is a cool, moist but not soggy site, a layer of dried leaves in the winter and some protection from slugs when they are young. Our population started with a bag of seed of C. giganteum var yunnanense given to us by Liz Carter about 15 years ago. They germinated very well, and at about 2 years old I risked some of them in the garden. It was a mistake. They were eaten. However, at 3 years old they survived. (I think there is some mathematical relationship between rate of growth, stored energy and slug numbers that determines whether herbaceous plants will survive the onslaught. I think this also applies to aralia, ligularia, tricyrtis etc. ) At about 6 years old they started to flower. Whilst the flowering stem dies, if you root around the base you will find offsets of varying sizes. In my experience if these are about the size of a fat daffodil bulb they can be planted out straight away. If smaller, grow them on in pots for a year or so. We now have several patches in which at least 2 or 3 will flower every year, whilst the smaller ones grow on. -

North American Botanic Garden Strategy for Plant Conservation 2016-2020 Botanic Gardens Conservation International

Nova Southeastern University NSUWorks Marine & Environmental Sciences Faculty Reports Department of Marine and Environmental Sciences 1-1-2016 North American Botanic Garden Strategy for Plant Conservation 2016-2020 Botanic Gardens Conservation International American Public Gardens Association Asociacion Mexicana de Jardines Center for Plant Conservation Plant Conservation Alliance See next page for additional authors Find out more information about Nova Southeastern University and the Halmos College of Natural Sciences and Oceanography. Follow this and additional works at: https://nsuworks.nova.edu/occ_facreports Part of the Plant Sciences Commons Authors Botanic Gardens Conservation International, American Public Gardens Association, Asociacion Mexicana de Jardines, Center for Plant Conservation, Plant Conservation Alliance, Pam Allenstein, Robert Bye, Jennifer Ceska, John Clark, Jenny Cruse-Sanders, Gerard Donnelly, Christopher Dunn, Anne Frances, David Galbraith, Jordan Golubov, Gennadyi Gurman, Kayri Havens, Abby Hird Meyer, Douglas Justice, Edelmira Linares, Maria Magdalena Hernandez, Beatriz Maruri Aguilar, Mike Maunder, Ray Mims, Greg Mueller, Jennifer Ramp Neale, Martin Nicholson, Ari Novy, Susan Pell, John J. Pipoly III, Diane Ragone, Peter Raven, Erin Riggs, Kate Sackman, Emiliano Sanchez Martinez, Suzanne Sharrock, Casey Sclar, Paul Smith, Murphy Westwood, Rebecca Wolf, and Peter Wyse Jackson North American Botanic Garden Strategy For Plant Conservation 2016-2020 North American Botanic Garden Strategy For Plant Conservation 2016-2020 Acknowledgements Published January 2016 by Botanic Gardens Conservation International. Support from the United States Botanic Garden, the American Public Gardens Association, and the Center for Plant Conservation helped make this publication possible. The 2016-2020 North American Botanic Garden Strategy for Plant Conservation is dedicated to the late Steven E. Clemants, who so diligently and ably led the creation of the original North American Strategy published in 2006. -

An Encyclopedia of Shade Perennials This Page Intentionally Left Blank an Encyclopedia of Shade Perennials

An Encyclopedia of Shade Perennials This page intentionally left blank An Encyclopedia of Shade Perennials W. George Schmid Timber Press Portland • Cambridge All photographs are by the author unless otherwise noted. Copyright © 2002 by W. George Schmid. All rights reserved. Published in 2002 by Timber Press, Inc. Timber Press The Haseltine Building 2 Station Road 133 S.W. Second Avenue, Suite 450 Swavesey Portland, Oregon 97204, U.S.A. Cambridge CB4 5QJ, U.K. ISBN 0-88192-549-7 Printed in Hong Kong Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Schmid, Wolfram George. An encyclopedia of shade perennials / W. George Schmid. p. cm. ISBN 0-88192-549-7 1. Perennials—Encyclopedias. 2. Shade-tolerant plants—Encyclopedias. I. Title. SB434 .S297 2002 635.9′32′03—dc21 2002020456 I dedicate this book to the greatest treasure in my life, my family: Hildegarde, my wife, friend, and supporter for over half a century, and my children, Michael, Henry, Hildegarde, Wilhelmina, and Siegfried, who with their mates have given us ten grandchildren whose eyes not only see but also appreciate nature’s riches. Their combined love and encouragement made this book possible. This page intentionally left blank Contents Foreword by Allan M. Armitage 9 Acknowledgments 10 Part 1. The Shady Garden 11 1. A Personal Outlook 13 2. Fated Shade 17 3. Practical Thoughts 27 4. Plants Assigned 45 Part 2. Perennials for the Shady Garden A–Z 55 Plant Sources 339 U.S. Department of Agriculture Hardiness Zone Map 342 Index of Plant Names 343 Color photographs follow page 176 7 This page intentionally left blank Foreword As I read George Schmid’s book, I am reminded that all gardeners are kindred in spirit and that— regardless of their roots or knowledge—the gardening they do and the gardens they create are always personal. -

Ecological Checklist of the Missouri Flora for Floristic Quality Assessment

Ladd, D. and J.R. Thomas. 2015. Ecological checklist of the Missouri flora for Floristic Quality Assessment. Phytoneuron 2015-12: 1–274. Published 12 February 2015. ISSN 2153 733X ECOLOGICAL CHECKLIST OF THE MISSOURI FLORA FOR FLORISTIC QUALITY ASSESSMENT DOUGLAS LADD The Nature Conservancy 2800 S. Brentwood Blvd. St. Louis, Missouri 63144 [email protected] JUSTIN R. THOMAS Institute of Botanical Training, LLC 111 County Road 3260 Salem, Missouri 65560 [email protected] ABSTRACT An annotated checklist of the 2,961 vascular taxa comprising the flora of Missouri is presented, with conservatism rankings for Floristic Quality Assessment. The list also provides standardized acronyms for each taxon and information on nativity, physiognomy, and wetness ratings. Annotated comments for selected taxa provide taxonomic, floristic, and ecological information, particularly for taxa not recognized in recent treatments of the Missouri flora. Synonymy crosswalks are provided for three references commonly used in Missouri. A discussion of the concept and application of Floristic Quality Assessment is presented. To accurately reflect ecological and taxonomic relationships, new combinations are validated for two distinct taxa, Dichanthelium ashei and D. werneri , and problems in application of infraspecific taxon names within Quercus shumardii are clarified. CONTENTS Introduction Species conservatism and floristic quality Application of Floristic Quality Assessment Checklist: Rationale and methods Nomenclature and taxonomic concepts Synonymy Acronyms Physiognomy, nativity, and wetness Summary of the Missouri flora Conclusion Annotated comments for checklist taxa Acknowledgements Literature Cited Ecological checklist of the Missouri flora Table 1. C values, physiognomy, and common names Table 2. Synonymy crosswalk Table 3. Wetness ratings and plant families INTRODUCTION This list was developed as part of a revised and expanded system for Floristic Quality Assessment (FQA) in Missouri. -

Basal Eudicots • Already Looked at Basal Angiosperms Except Monocots

Basal Eudicots • already looked at basal angiosperms except monocots Basal Eudicots • Eudicots are the majority of angiosperms and defined by 3 pored pollen - often called tricolpates . transition from basal angiosperm to advanced eudicot . Basal Eudicots Basal Eudicots • tricolpate pollen: only • tricolpate pollen: a morphological feature derived or advanced defining eudicots character state that has consistently evolved essentially once • selective advantage for pollen germination Basal Eudicots Basal Eudicots • basal eudicots are a grade at the • basal eudicots are a grade at the base of eudicots - paraphyletic base of eudicots - paraphyletic • morphologically are transitionary • morphologically are transitionary core eudicots core eudicots between basal angiosperms and the between basal angiosperms and the core eudicots core eudicots lotus lily • examine two orders only: sycamore Ranunculales - 7 families Proteales - 3 families trochodendron Dutchman’s breeches marsh marigold boxwood Basal Eudicots Basal Eudicots *Ranunculaceae (Ranunculales) - *Ranunculaceae (Ranunculales) - buttercup family buttercup family • largest family of the basal • 60 genera, 2500 species • perennial herbs, sometimes eudicots woody or herbaceous climbers or • distribution centered in low shrubs temperate and cold regions of the northern and southern hemispheres Ranunculaceae baneberry clematis anemone Basal Eudicots Basal Eudicots marsh marigold *Ranunculaceae (Ranunculales) - *Ranunculaceae (Ranunculales) - CA 3+ CO (0)5+ A ∞∞ G (1)3+ buttercup family buttercup -

Large-Scale Propagation and Production of Native Woodland Perennials 313

Large-Scale Propagation and Production of Native Woodland Perennials 313 Large-Scale Propagation and Production of Native Woodland Perennials© William Cullina New England Wild Flower Society, 180 Hemenway Rd, Framingham, Massachusetts, 01701 U.S.A. Email: [email protected] Native woodland perennials are a source of frustration for propagators, because is- sues concerning seed viability, extended germination times, and slow and seasonal growth of seedlings discourage large-scale propagation and production. However, with proper seed handling and pretreatments as well as a “liner” approach to pro- duction, I believe that large-scale production is possible and profitable. INTRODUCTION The demand for native plants grows greater every year. Access to improved culti- vars, increasing sophistication on the part of the gardening public, and increased interest from government and the commercial sector have all contributed to this phenomenon. Many species can be easily and quickly produced from cuttings or seed (i.e., Asteraceae, Scrophulariaceae, etc.), but others — especially the woodland wildflowers commonly known as spring ephemerals — have proved especially dif- ficult to accommodate in large-scale perennial production. Genera such asTrillium, Cypripedium, Polygonatum, and Hepatica, while outstanding garden subjects that command premium prices, have developed a reputation for recalcitrance that is only partly deserved. Woodland wildflowers and bulbs are still supplied primar- ily as bare root, wild-collected stock. Thankfully, this questionable practice is now looked down upon by most of the perennial industry and consumers alike. Although collected plants are extremely cheap, we have found through experience that consumers will pay premium prices for genuinely nursery-raised material if it is available as an alternative. -

Estimating the Number of Undiscovered Rare Plant Occurrences in Southern Ontario

Estimating the number of undiscovered rare plant occurrences in Southern Ontario By Elise S. Urness A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Affairs in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Biology Carleton University Ottawa, Ontario © 2020, Elise S. Urness 1 ABSTRACT We often do not know the total number of extant populations of species of conservation concern. Species distribution models (SDMs) can be used to predict the probability of species’ occurrence. We tested the use of validated SDMs to estimate the number of occurrences of rare plant species across Southern Ontario. We built SDMs for six rare species using known occurrence records and then surveyed 282 new sites and used presence/absence records from these sites to predict probability of occurrence based on the SDM output. We summed these probabilities to estimate the number of occurrences on the landscape. We then used simulation exercises to estimate the likelihood that our sample size was large enough to make a confident estimate. Simulation results showed that the true number of extant occurrences can be overestimated with fewer than 1,000 SDM-directed survey sites. Therefore, our estimates may be overestimates of the true number of extant occurrences, and more surveys will be required to obtain more accurate estimates. This technique for estimating the number of remaining rare species occurrences will inform researchers and managers as they prioritize time and money towards decisions around species recovery and protection, and where to allocate additional survey effort. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First and foremost, I would like to thank God for giving me this amazing opportunity as well as providing me with the mental strength and emotional fortitude to reach the end. -

Stylophorum (PDF)

Flora of China 7: 284–285. 2008. 8. STYLOPHORUM Nuttall, Gen. N. Amer. Pl. 2: 7. 1818. 金罂粟属 jin ying su shu Zhang Mingli (张明理); Christopher Grey-Wilson Herbs, perennial, yellow or orange lactiferous, rather brittle. Stems 1(–3), erect, terete, striate, pubescent or glabrous. Basal leaves few, long petiolate; blade pinnatipartite or pinnatisect; lobes deeply undulate or irregularly serrate. Cauline leaves 2–7, shortly petiolate, apical 2 leaves (rarely 3) almost opposite, or almost terminal from peduncle bottom, shortly petiolate or sessile; blade like basal leaves. Flowers in corymb or umbel, pedunculate, bracteate. Sepals 2, caducous, broadly ovate, villous. Petals 4, yellow, subor- bicular, imbricately arranged. Stamens many (20 or more); filaments filiform; anthers oblong or linear-oblong, 2-celled, longitu- dinally divided. Ovary ovoid or terete, pubescent, 1-loculed, 2–4-carpellate; ovules many; styles terete; stigmas capitate, 2–4-lobed, lobes alternate with placentas. Capsule narrowly ovoid or narrowly oblong, pubescent, 2–4-valvate from apex to base, with many seeds. Seeds small, tessellate, cristately carunculate. Three species: China, one in North America (Atlantic coast); two species (both endemic) in China. 1a. Plant yellow lactiferous, villous; cauline leaves 4–7; stigma lobes small; capsules oblong, 2.5–3.5 cm, densely brown curved villous .................................................................................................................................. 1. S. sutchuenense 1b. Plant orange-red lactiferous, glabrous; cauline leaves 2 or 3; stigma lobes large, almost flat; capsules narrowly terete, 5–8 cm, pubescent .......................................................................................................................... 2. S. lasiocarpum 1. Stylophorum sutchuenense (Franchet) Fedde in Engler, Bot. 金罂粟 jin ying su Jahrb. Syst. 36(Beibl. 82): 45. 1905 [“sutchuense”]. Chelidonium lasiocarpum Oliver, Hooker’s Icon. -

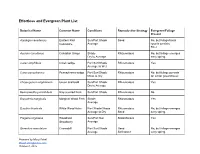

Effortless and Evergreen Plant List

Effortless and Evergreen Plant List Botanical Name Common Name Conditions Reproductive Strategy Evergreen/Foliage Present Aquilegia canadensis Eastern Red Sun/Part Shade Seed No, but foliage/basal Columbine Average rosette persists. Filler Asarum canadense Canadian Ginger Shade Rhizomatous No, but foliage emerges Dry to Average early spring. Carex amphibola Creek sedge Part Sun/Shade Rhizomatous Yes Average to Wet Carex pensylvanica Pennsylvania sedge Part Sun/Shade Rhizomatous No, but foliage persists Moist to Dry for winter groundcover. Chrysogonum virginianum Green and Gold Sun/Part Shade Rhizomatous Yes Dry to Average Dennstaedtia punctilobula Hay-scented Fern Sun/Part Shade Rhizomatous No Dryopteris marginalis Marginal Wood Fern Shade Rhizomatous Yes Average Eurybia divaricata White Wood Aster Part Shade/Shade Rhizomatous No, but foliage emerges Average to Dry Seed early spring. Fragaria virginiana Woodland Sun/Part Sun Stoloniferous Yes Strawberry Average Geranium maculatum Cranesbill Part Sun/Shade Seed No, but foliage emerges Average Self-sower early spring. Prepared by Missy Fabel [email protected] October 5, 2019 Effortless and Evergreen Plant List Botanical Name Common Name Conditions Reproductive Strategy Evergreen/Foliage Present Heuchera villosa Alumroot Part Sun/Shade Rhizomatous Yes ‘Autumn Bride’ Dry to Average Lobelia cardinalis Cardinal Flower Sun/Part Shade Seed No, but basal rosette Moist to Wet Biennial persists. Lobelia siphilitica Blue Lobelia Part Shade/Shade Seed No, but basal rosette Average to Moist Biennial -

The Regulation of Ontogenetic Diversity in Papaveraceae Compound Leaf Development

The Regulation of Ontogenetic Diversity in Papaveraceae Compound Leaf Development A thesis presented to the faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Science Alastair R. Plant August 2013 © 2013 Alastair R. Plant. All Rights Reserved. 2 This thesis titled The Regulation of Ontogenetic Diversity in Papaveraceae Compound Leaf Development by ALASTAIR R PLANT has been approved for the Department of Environmental and Plant Biology and the College of Arts and Sciences by Stefan Gleissberg Assistant Professor of Environmental and Plant Biology Robert Frank Dean, College of Arts and Sciences 3 ABSTRACT PLANT, ALASTAIR R., M.S., August 2013, Plant Biology The Regulation of Ontogenetic Diversity in Papaveraceae Compound Leaf Development Director of Thesis: Stefan Gleissberg The leaf is almost ubiquitous throughout land plants but due to its complex and flexible developmental program is highly morphologically variable between taxa. Description of the functions of regulatory genes key to leaf development in different evolutionary lineages allows the study of changes in developmental mechanisms through evolutionary time as a means for anatomical and morphological diversification. The roles of homologs of CINCINNATA-like TCP family genes, ARP genes, and Class I KNOX genes were investigated in two members of the Papaveraceae, a basal eudicot lineage positioned in between major angiosperm groups, by phylogenetic analysis, in situ hybridization, expression profiling by quantitative polymerase chain reaction, and virus- induced gene silencing in Eschscholzia californica and Cysticapnos vesicaria. Expression data were similar to those for homologous genes in core eudicot species, however, some gene functions found in core eudicots were not associated with basal eudicot homologs, and so have either been gained or lost from the ancestral state. -

Papaveraceae – Poppy Family

PAPAVERACEAE – POPPY FAMILY Plant: herbs, rarely shrubs or trees Stem: sap sometimes milky or colored (yellow or red) Root: Leaves: basal and/or stem leaves, mostly alternate but also opposite and whorled, simple or deeply lobed or cut; no stipules Flowers: perfect, regular (actionomorphic); 2-3 sepals, united or not; 4 or 6 petals, sometimes 8-12 or rarely none, showy and often large; numerous stamens usually spirally arranged; ovary superior, 2 to many carpels Fruit: capsule, often irregularly shaped Other: many ornamentals and of course opium is taken from one; Dicotyledons Group Genera: 30+ genera; locally Chelidonium (celandine), Glaucium (horned poppy), Papaver (poppy), Sanguinara (bloodroot), Stylophorum (celandine poppy) WARNING – family descriptions are only a layman’s guide and should not be used as definitive PAPAVERACEAE – POPPY FAMILY [Bluestem] Prickly Poppy; Argemone albiflora Hornem. Lesser Celandine [Poppy]; Chelidonium majus L. (Introduced) Corn Poppy; Papaver rhoeas L. (Introduced) Bloodroot; Sanguinaria canadensis L. Wood [Celandine] Poppy; Stylophorum diphyllum (Michx.) Nutt. [Bluestem] Prickly Poppy USDA Argemone albiflora Hornem. Papaveraceae (Poppy Family) Batesville, Independence County, Arkansas Notes: large 6-petaled flower, white, petals very thin and often seem wrinkled; leaves large, pinnatifid, mostly near base, not clasping, with long hairs; stem slender, with spines; stem glabrous with spines, sap clear; fruit ovoid and spiny; late spring to summer (often an introduced species) [V Max Brown, 2009] Lesser Celandine [Poppy] USDA Chelidonium majus L. (Introduced) Papaveraceae (Poppy Family) Maumee River Metroparks, Lucas County, Ohio Notes: 4-petaled flower, yellow, petals 10-15mm long; both stem and basal leaves deeply lobed and divided; juice yellow; fruit erect, long and thin; plant very branched; spring to summer [V Max Brown, 2004] Corn Poppy USDA Papaver rhoeas L.