Indians, Environment, and Identity on the Borders of American Literature

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NATIVE AMERICAN LITERATURE a Brief Introduction and Anthology

NATIVE AMERICAN LITERATURE A Brief Introduction and Anthology Gerald Vizenor University of California Berkeley The HarperCollins Literary Mosaic Series Ishmael Reed General Editor University of California Berkeley HARPERCOLUNSCOLLEGEPUBLISHERS Contents Foreword by Ishmael Reed Introduction AUTOBIOGRAPHY William Apess (1798-?) A Son of the Forest Preface 20 Chapter I 20 Chapter II 24 Chapter III 28 Luther Standing Bear (1868-1939) My People the Sioux Preface 33 First Days at Carlisle 33 John Rogers (1890-?) Return to White Earth 46 N Scott Momaday (b 1934) The Way to Rainy Mountain [Introduction] 60 The Names 65 Gerald VTzenor(b 1934) Measuring My Blood 69 Maria Campbell (b 1940) The Little People 76 Louis Owens (b 1948) Motion of Fire and Form 83 Wendy Rose (b 1948) Neon Scars 95 FICTION John Joseph Mathews (1894-1979) The Birth of Challenge 106 iv Native American Literature D Arcy McNickle (1904-1977) A Different World Elizabeth Cook Lynn (b 1930) A Good Chance N Scott Momaday (b 1934) The Rise of the Song Gerald Vizenor (b 1934) Hearthnes Paula Gunn Allen (b 1939) Someday Soon James Welch (b 1940) The Earthboy Place Thomas King (b 1943) Maydean Joe Leslie Marmon Silko (b 1948) Call That Story Back Louis Owens (b 1948) The Last Stand Betty Louise Bell (b 1949) In the Hour of the Wolf Le Anne Howe (b 1951) Moccasins Don t Have High Heels Evelina Zuni Lucero (b 1953) Deer Dance Louise Erdnch (b 1954) Lipsha Mornssey Kimberly Blaeser (b 1955) A Matter of Proportion Gordon Henry Jr (b 1955) Arthur Boozhoo on the Nature of Magic POETRY Mary -

The Evolution of Batman and His Audiences

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University English Theses Department of English 12-2009 Static, Yet Fluctuating: The Evolution of Batman and His Audiences Perry Dupre Dantzler Georgia State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_theses Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Dantzler, Perry Dupre, "Static, Yet Fluctuating: The Evolution of Batman and His Audiences." Thesis, Georgia State University, 2009. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_theses/73 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of English at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STATIC, YET FLUCTUATING: THE EVOLUTION OF BATMAN AND HIS AUDIENCES by PERRY DUPRE DANTZLER Under the Direction of H. Calvin Thomas ABSTRACT The Batman media franchise (comics, movies, novels, television, and cartoons) is unique because no other form of written or visual texts has as many artists, audiences, and forms of expression. Understanding the various artists and audiences and what Batman means to them is to understand changing trends and thinking in American culture. The character of Batman has developed into a symbol with relevant characteristics that develop and evolve with each new story and new author. The Batman canon has become so large and contains so many different audiences that it has become a franchise that can morph to fit any group of viewers/readers. Our understanding of Batman and the many readings of him gives us insight into ourselves as a culture in our particular place in history. -

Native American Poets and the Voices of History in the Present Tense

The Spirits Still Among Us: Native American Poets and the Voices of History in the Present Tense Sydney Hunt Coffin Edison/Fareira High School Overview Introduction Rationale Objectives Strategies Classroom Activites/Lesson Plans Annotated Bibliography/Resources Appendices/Standards Endnotes What is life? It is the flash of a firefly in the night. It is the breath of a buffalo in the wintertime. It is the little shadow that runs across the grass and loses itself in the sunset.1 Overview So spoke Crowfoot, orator of the Blackfoot Confederacy in 1890, above, on his deathbed. Even while this was not identified as poetry at the time, much of the wisdom of this Native American speaker comes across to readers poetically. Similarly, much of the poetry of Native American poets can be read simply as wisdom. Though there was a significant number of tribes, and a tremendous number of people at the time of the European invasion, each tribal language displays simultaneously a distinct identity as well as a variety of individual voices. However, the published poetry from native authors across the vast spectrum of tribal affiliations between the beginning and end of the 20th century reveal three unifying themes: (1) respecting a common reverence for the land from which each tribe came, through ceremonial poetry and songs; (2) respecting past traditions, including rituals, truths, and the words of one’s elders; and (3) expressing political criticism, even activism. Editor Kenneth Rosen writes “There may seem to be a great deal of distance between the Navajo Blessing Way chants and a contemporary poem about the confrontations at Wounded Knee, but it’s really not that far to go”.2 In fact, this curriculum unit around Native American poetry endeavors to keep pace with the ongoing experiences of native people, whose words continue to speak to the land, its mysteries, and its voice. -

“The National Voice” Across the Bayard and Ringo Stories

UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA GRADUATE COLLEGE POPULAR FAULKNER: THE DEVELOPMENT OF “THE NATIONAL VOICE” ACROSS THE BAYARD AND RINGO STORIES A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS By WILLIAM WILDE JANUARY VI Norman, Oklahoma 2018 POPULAR FAULKNER: THE DEVELOPMENT OF “THE NATIONAL VOICE” ACROSS THE BAYARD AND RINGO STORIES A THESIS APPROVED FOR THE DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH BY ______________________________ Dr. James Zeigler, Chair ______________________________ Dr. Daniela Garofalo ______________________________ Dr. William Henry McDonald © Copyright by WILLIAM WILDE JANUARY VI 2018 All Rights Reserved. To Claire, as a monument to our adventure in Oklahoma. Acknowledgements This project is in many ways the culmination of everything I have done before, and thus it is necessary to acknowledge everyone I have had the pleasure to have known the past three years in the University of Oklahoma English Department: faculty, staff, and my fellow graduate students. In particular, I would like to thank both Dr. McDonald and Dr. Garofalo for not only serving on my committee, but for teaching seminars so influential that they changed the way that I viewed the world and, subsequently, my future plans. In a similar vein, I would like to thank Dr. John Burke and Dr. William Ulmer at the University of Alabama, as I would have never even been here without their part in shaping my formless undergraduate curiosity into the more disciplined inquisitiveness of a scholar. Most of all, I am indebted to my Chair, Dr. James Zeigler, who has over the past three years listened carefully to every road not taken by this work, and always provided clear, helpful feedback as well as a sense of positivity that has made all the difference in its completion. -

Many Voices Press Flathead Valley Community College Table of Contents

New Poets of the American West -An anthology of poets from eleven Western states- Uni Gottingen 230 r to 2, ft 341 Many Voices Press Flathead Valley Community College Table of Contents Editor's Note: "In This Spirit I Gathered These Poems" by Lowell Jaeger 1 Introduction: "Many Voices, Many Wests" by Brady Harrison 7 Arizona Dick Bakken Going into Moonlight 20 Sherwin Bitsui (excerpted from: Flood Song) 21 Jefferson Carter Match Race 22 A Centaur 22 Virgil Chabre Wyoming Miners 23 David Chorlton Everyday Opera 24 Jim Harrison Blue 25 Rene Char II 25 Love 26 Larson's Holstein Bull 26 Cynthia Hogue That Wild Chance of Living (2001) 27 Will Inman The Bones that Humans Lacked 28 given names 28 mesquite mother territory 29 To Catch the Truth 29 James Jay Mars Hill 30 Hershman John Two Parts Hydrogen, One Part Oxygen 31 Jane Miller xii (excerpted from Midnights) 32 Jim Natal The Half-Life of Memory 33 Sean Nevin The Carpenter Bee 34 Wildfire Triptych 34 Losing Solomon 37 Simon J. Ortiz just phoenix 38 Michael Rattee Spring 39 II David Ray The Sleepers 40 Illegals 41 Arizona Satori 41 The White Buffalo 42 Judy Ray These Days 43 Alberto Rfos Border Lines (Lineas Fronterizas) 44 Rabbits and Fire 45 Refugio's Hair 46 Mi Biblioteca Publica (My Public Library) 47 Rebecca Seiferle Ghost Riders in the Sky 48 Apache Tears 49 Leslie Marmon Silko How to Hunt Buffalo 50 Laurel Speer Buffalo Stones 52 Candyman 52 Luci Tapahonso After Noon in Yooto 53 Miles Waggener Direction 54 Nicole Walker Canister and Turkey Vulture 55 California Kim Addonizio Yes 58 In the Evening, 59 William Archila Blinking Lights 60 Ellen Bass GateC22 61 Women Walking 62 Ode to Dr. -

Finding Aid for the Faulkner Periodicals Collection (MUM00161)

University of Mississippi eGrove Archives & Special Collections: Finding Aids Library November 2020 Finding Aid for the Faulkner Periodicals Collection (MUM00161) Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/finding_aids Recommended Citation Faulkner Periodicals Collection, Archives and Special Collections, J.D. Williams Library, The University of Mississippi This Finding Aid is brought to you for free and open access by the Library at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Archives & Special Collections: Finding Aids by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Finding Aid for the Faulkner Periodicals Collection (MUM00161) Questions? Contact us! The Faulkner Periodicals Collection is open for research. Finding Aid for the Faulkner Periodicals Collection Table of Contents Descriptive Summary Administrative Information Subject Terms Collection History Scope and Content Note User Information Related Material Arrangement Container List Descriptive Summary Title: Faulkner Periodicals Collection Dates: 1930-1997 Collector: Wynn, Douglas C. ; Wynn, Leila Clark ; University of Mississippi. Dept. of Archives and Special Collections Physical Extent: 27 full Hollinger boxes ; 6 half boxes ; 1 oversize box ; 22 cartons (35.85 linear feet) Repository: University of Mississippi. Department of Archives and Special Collections. University, MS 38677, USA Identification: MUM00161 Language of Material: English Abstract: Collection of magazine and newspaper articles written by or concerning William Faulkner and University of Mississippi Yearbooks referencing Faulkner. Administrative Information Processing Information Collections processed by Archives and Special Collections staff. Series III-IV, Periodicals by Faulkner and Periodicals about Faulkner, originally processed by Jill Applebee and Amanda Strickland, August-September 1999. Multiple collections combined into single finding aid and encoded by Jason Kovari, August 2009. -

WILLIAM FAULKNER, Collected Stories

WILLIAM FAULKNER Collected Stories Contents I. THE COUNTRY Barn Burning Shingles for the Lord The Tall Men A Bear Hunt Two Soldiers Shall Not Perish II. THE VILLAGE A Rose for Emily Hair Centaur in Brass Dry September Death Drag Elly Uncle Willy Mule in the Yard That Will Be Fine That Evening Sun III. THE WILDERNESS Red Leaves A Justice A Courtship Lo! IV. THE WASTELAND Ad Astra Victory Crevasse Turnabout All the Dead Pilots V. THE MIDDLE GROUND Wash Honor Dr. Martin Fox Hunt Pennsylvania Station Artist at Home The Brooch Grandmother Millard Golden Land There Was a Queen Mountain Victory VI. BEYOND Beyond Black Music The Leg Mistral Divorce in Naples Carcassonne I THE COUNTRY Barn Burning Shingles for the Lord The Tall Men A Bear Hunt Two Soldiers Shall Not Perish Barn Burning THE STORE in which the Justice of the Peace's court was sitting smelled of cheese. The boy, crouched on his nail keg at the back of the crowded room, knew he smelled cheese, and more: from where he sat he could see the ranked shelves close-packed with the solid, squat, dynamic shapes of tin cans whose labels his stomach read, not from the lettering which meant nothing to his mind but from the scarlet devils amid the silver curve of fish this, the cheese which he knew he smelled and the hermetic meat which his intestines believed he smelled coming in intermittent gusts momentary and brief between the other constant one, the smell and sense just a little of fear because mostly of despair and grief, the old fierce pull of blood. -

William Faulkner

William Faulkner: An Inventory of His Collection at the Harry Ransom Center Descriptive Summary Creator: Faulkner, William, 1897-1962 Title: William Faulkner Collection Dates: 1912-1970 (bulk 1920-1942) Extent: 13 document boxes, 13 galley files (gf) (5.26 linear feet) Abstract: The William Faulkner Collection contains drafts and publishing proofs of Faulkner's novels, short stories, poetry, and scripts; correspondence; and material about the author William Cuthbert Faulkner originating from a variety of sources. Language: English Access: Open for research. Some materials restricted for preservation; copies available. Curatorial permission needed for access to originals. Administrative Information Acquisition: Gifts and purchases, 1957-2002 Processed by: Amy E. Armstrong, 2010 Repository: The University of Texas at Austin, Harry Ransom Center Faulkner, William, 1897-1962 Biographical Sketch William Cuthbert, born on September 25, 1897, in New Albany, Mississippi, was the first of four children born to Maud and Murry Falkner. In 1902, the Falkner family moved to Oxford, Mississippi. Both accomplished painters, Faulkner's mother and maternal grandmother, Lelia Butler, instilled into "Billy" an appreciation for music, literature, and art. It was perhaps Faulkner's legendary great-grandfather, however, William Clark Falkner--an infamous Confederate soldier, lawyer, railroad developer, and successful author--who provided Faulkner with his spirited personality and gift for storytelling. Though smart, Faulkner had a difficult time in school because of his chronic truancy and dropped out of high school after the tenth grade. He met Phil Stone, four years older and the son of a prominent lawyer and banker, in 1914. Stone took an interest in Faulkner's early writing and mentored him in life and literature; he suggested authors and works for Faulkner to read and introduced him to the more colorful elements of local gambling, roadhouse, and bordello culture. -

American Book Awards 2004

BEFORE COLUMBUS FOUNDATION PRESENTS THE AMERICAN BOOK AWARDS 2004 America was intended to be a place where freedom from discrimination was the means by which equality was achieved. Today, American culture THE is the most diverse ever on the face of this earth. Recognizing literary excel- lence demands a panoramic perspective. A narrow view strictly to the mainstream ignores all the tributaries that feed it. American literature is AMERICAN not one tradition but all traditions. From those who have been here for thousands of years to the most recent immigrants, we are all contributing to American culture. We are all being translated into a new language. BOOK Everyone should know by now that Columbus did not “discover” America. Rather, we are all still discovering America—and we must continue to do AWARDS so. The Before Columbus Foundation was founded in 1976 as a nonprofit educational and service organization dedicated to the promotion and dissemination of contemporary American multicultural literature. The goals of BCF are to provide recognition and a wider audience for the wealth of cultural and ethnic diversity that constitutes American writing. BCF has always employed the term “multicultural” not as a description of an aspect of American literature, but as a definition of all American litera- ture. BCF believes that the ingredients of America’s so-called “melting pot” are not only distinct, but integral to the unique constitution of American Culture—the whole comprises the parts. In 1978, the Board of Directors of BCF (authors, editors, and publishers representing the multicultural diversity of American Literature) decided that one of its programs should be a book award that would, for the first time, respect and honor excellence in American literature without restric- tion or bias with regard to race, sex, creed, cultural origin, size of press or ad budget, or even genre. -

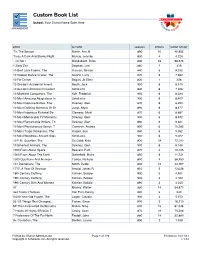

Custom Book List

Custom Book List School: Your District Name Goes Here MANAGEMENT BOOK AUTHOR LEXILE® POINTS WORD COUNT 'Tis The Season Martin, Ann M. 890 10 40,955 'Twas A Dark And Stormy Night Murray, Jennifer 830 4 4,224 ...Or Not? Mandabach, Brian 840 23 98,676 1 Zany Zoo Degman, Lori 860 1 415 10 Best Love Poems, The Hanson, Sharon 840 6 8,332 10 Coolest Dance Crazes, The Swartz, Larry 870 6 7,660 10 For Dinner Bogart, Jo Ellen 820 1 328 10 Greatest Accidental Inventi Booth, Jack 900 6 8,449 10 Greatest American President Scholastic 840 6 7,306 10 Mightiest Conquerors, The Koh, Frederick 900 6 8,034 10 Most Amazing Adaptations In Scholastic 900 6 8,409 10 Most Decisive Battles, The Downey, Glen 870 6 8,293 10 Most Defining Moments Of Th Junyk, Myra 890 6 8,477 10 Most Ingenious Fictional De Clemens, Micki 870 6 8,687 10 Most Memorable TV Moments, Downey, Glen 900 6 8,912 10 Most Remarkable Writers, Th Downey, Glen 860 6 9,321 10 Most Revolutionary Songs, T Cameron, Andrea 890 6 10,282 10 Most Tragic Romances, The Harper, Sue 860 6 9,052 10 Most Wondrous Ancient Sites Scholastic 900 6 9,022 10 P.M. Question, The De Goldi, Kate 830 18 72,103 10 Smartest Animals, The Downey, Glen 900 6 8,148 1000 Facts About Space Beasant, Pam 870 4 10,145 1000 Facts About The Earth Butterfield, Moira 850 6 11,721 1000 Questions And Answers Tames, Richard 890 9 38,950 101 Dalmatians, The Smith, Dodie 830 12 44,767 1777: A Year Of Decision Arnold, James R. -

Title of Book/Magazine/Newspaper Author/Issue Datepublisher Information Her Info

TiTle of Book/Magazine/newspaper auThor/issue DaTepuBlisher inforMaTion her info. faciliT Decision DaTe censoreD appealeD uphelD/DenieD appeal DaTe fY # American Curves Winter 2012 magazine LCF censored September 27, 2012 Rifts Game Master Guide Kevin Siembieda book LCF censored June 16, 2014 …and the Truth Shall Set You Free David Icke David Icke book LCF censored October 5, 2018 10 magazine angel's pleasure fluid issue magazine TCF censored May 15, 2017 100 No-Equipment Workout Neila Rey book LCF censored February 19,2016 100 No-Equipment Workouts Neila Rey book LCF censored February 19,2016 100 of the Most Beautiful Women in Painting Ed Rebo book HCF censored February 18, 2011 100 Things You Will Never Find Daniel Smith Quercus book LCF censored October 19, 2018 100 Things You're Not Supposed To Know Russ Kick Hampton Roads book HCF censored June 15, 2018 100 Ways to Win a Ten-Spot Comics Buyers Guide book HCF censored May 30, 2014 1000 Tattoos Carlton Book book EDCF censored March 18, 2015 yes yes 4/7/2015 FY 15-106 1000 Tattoos Ed Henk Schiffmacher book LCF censored December 3, 2007 101 Contradictions in the Bible book HCF censored October 9, 2017 101 Cult Movies Steven Jay Schneider book EDCF censored September 17, 2014 101 Spy Gadgets for the Evil Genius Brad Graham & Kathy McGowan book HCF censored August 31, 2011 yes yes 9/27/2011 FY 12-009 110 Years of Broadway Shows, Stories & Stars: At this Theater Viagas & Botto Applause Theater & Cinema Books book LCF censored November 30, 2018 113 Minutes James Patterson Hachette books book -

Heret, by Illustrator and Comics Creator Dan Mucha and Toulouse Letrec Were in Brereton

Featured New Items FAMOUS AMERICAN ILLUSTRATORS On our Cover Specially Priced SOI file copies from 1997! Our NAUGHTY AND NICE The Good Girl Art of Highest Recommendation. By Bruce Timm Publisher Edition Arpi Ermoyan. Fascinating insights New Edition. Special into the lives and works of 82 top exclusive Publisher’s artists elected to the Society of Hardcover edition, 1500. Illustrators Hall of Fame make Highly Recommended. this an inspiring reference and art An extensive survey of book. From illustrators such as N.C. Bruce Timm’s celebrated Wyeth to Charles Dana Gibson to “after hours” private works. Dean Cornwell, Al Parker, Austin These tastefully drawn Briggs, Jon Whitcomb, Parrish, nudes, completed purely for Pyle, Dunn, Peak, Whitmore, Ley- fun, are showcased in this endecker, Abbey, Flagg, Gruger, exquisite new release. This Raleigh, Booth, LaGatta, Frost, volume boasts over 250 Kent, Sundblom, Erté, Held, full-color or line and pencil Jessie Willcox Smith, Georgi, images, each one full page. McGinnis, Harry Anderson, Bar- It’s all about sexy, nubile clay, Coll, Schoonover, McCay... girls: partially clothed or fully nude, of almost every con- the list of greats goes on and on. ceivable description and temperament. Girls-next-door, Society of Illustrators, 1997. seductresses, vampires, girls with guns, teases...Timm FAMAMH. HC, 12x12, 224pg, FC blends his animation style with his passion for traditional $40.00 $29.95 good-girl art for an approach that is unmistakably all his JOHN HASSALL own. Flesk, 2021. Mature readers. NOTE: Unlike the The Life and Art of the Poster King first, Timm didn’t sign this second printing.