University of Alberta

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Here I Am a Novel Jonathan Safran Foer

Here I Am A Novel Jonathan Safran Foer A monumental new novel from the bestselling author of Everything Is Illuminated and Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close In the book of Genesis, when God calls out, “Abraham!” before ordering him to sacrifice his son Isaac, Abraham responds, “Here I am.” Later, when Isaac calls out, “My father!” before asking him why there is no animal to slaughter, Abraham responds, “Here I am.” How do we fulfill our conflicting duties as father, husband, and son; wife and mother; child and adult? Jew and American? How can we claim our own identities when our lives are linked so closely to others’? These are FICTION the questions at the heart of Jonathan Safran Foer’s first novel in eleven years--a work of extraordinary scope and heartbreaking intimacy. Farrar, Straus and Giroux | 9/6/2016 9780374280024 | $28.00 / $31.50 Can. Unfolding over four tumultuous weeks in present-day Washington, D.C., Hardcover | 592 pages Carton Qty: 0 | 9 in H | 6 in W Here I Am is the story of a fracturing family in a moment of crisis. As Brit., trans., 1st ser., dram.: Aragi, Inc. Jacob and Julia and their three sons are forced to confront the distances Audio: FSG between the lives they think they want and the lives they are living, a catastrophic earthquake sets in motion a quickly escalating conflict in the MARKETING Middle East. At stake is the very meaning of home--and the fundamental question of how much aliveness one can bear. Author Tour National Publicity National Advertising Showcasing the same high-energy inventiveness, hilarious irreverence, Web Marketing Campaign and emotional urgency that readers and critics loved in his earlier work, Library Marketing Campaign Reading Group Guide Here I Am is Foer’s most searching, hard-hitting, and grandly entertaining Advance Reader's Edition novel yet. -

Universitas Sam Ratulangi Fakultas Ilmu Budaya Manado 2013

PREPOSISI DALAM LIRIK LAGU ALBUM METROPOLIS KARYA DREAM THEATER JURNAL SKRIPSI Oleh RIZAL THOMAS 080912032 SASTRA INGGRIS UNIVERSITAS SAM RATULANGI FAKULTAS ILMU BUDAYA MANADO 2013 ABSTRACT This research entitled —3repositions in the Lyrics of Metropolis Album by Dream Theater“ is written to analyze and classify the form and the meaning of the prepositions that are used in that album. A preposition is a word that connects a noun or pronoun with a verb, adjective, or another noun or pronoun by indicating a relationship between the things for which they stand. The problems of this research are focused on what are the form and the meaning of prepositions that are found in the lyrics of Metropolis Album? The method used in this research is descriptive. The data of prepositions in this research were collected from the lyrics of Metropolis Album Part I and Part II by Dream Theater. The data of the prepositions found in the album are given number and wrote in the small cards. The result of this research shows that The Writer of the lyrics in this album used many prepositions to express meaning through the lyrics of his songs. The research used Quirk (1985) concept in analyzing the form of prepositions, whereas Curme (1986) concept is used in analyzing the meaning of prepositions found in the lyrics of the songs in the Metropolis Album. Key words: Prepositions, Songs : Dream Theater, Metropolis I. PENDAHULUAN Bahasa merupakan instrumen utama dalam berkomunikasi dan itu tidak dapat dipisahkan dari manusia. Bahasa digunakan untuk mengekspresikan perasaan, merespon fenomena, berbagi ide, dan juga kritik-mengkritik. -

A History of Bones Amanda C

Florida International University FIU Digital Commons FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations University Graduate School 2-27-2012 A History of Bones Amanda C. Hosey Florida International University, [email protected] DOI: 10.25148/etd.FI12050224 Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd Recommended Citation Hosey, Amanda C., "A History of Bones" (2012). FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 618. https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd/618 This work is brought to you for free and open access by the University Graduate School at FIU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of FIU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FLORIDA INTERNATIONAL, UNIVERSITY Miami, Florida A HISTORY OF BONES A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF FINE ARTS in CREATIVE WRITING by Amanda C. Hosey 2012 To: Dean Kenneth Furton College of Arts and Sciences This thesis written by Amanda C. Hosey, and entitled a History of Bones, having been approved in respect to style and intellectual content, is referred to you for judgment. We have read this thesis and recommend that it be approved. _______________________________________ Asher Milbauer _______________________________________ Campbell McGrath _______________________________________ Denise Duhamel, Major Professor Date of Defense: February 27, 2012 The thesis of Amanda C. Hosey is approved. _______________________________________ Dean Kenneth Furton College of Arts and Sciences _______________________________________ Dean Lakshmi N. Reddi University Graduate School Florida International University, 2012 ii ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS A HISTORY OF BONES by Amanda C. Hosey Florida International University, 2012 Miami, Florida Professor Denise Duhamel, Major Professor A HISTORY OF BONES is a collection of lyrical and narrative poems which examines the interconnectedness of humanity through recurrent physical images—bones, blood, hair, etc. -

Farrar, Straus & Giroux International Rights Guide

FARRAR, STRAUS & GIROUX INTERNATIONAL RIGHTS GUIDE FRANKFURT BOOK FAIR 2016 Devon Mazzone Director, Subsidiary Rights [email protected] 18 West 18th Street, New York, NY 10011 (212) 206-5301 Amber Hoover Foreign Rights Manager [email protected] 18 West 18th Street, New York, NY 10011 (212) 206-5304 2 FICTION Farrar, Straus and Giroux FSG Originals MCD/FSG Sarah Crichton Books 3 Baldwin, Rosecrans THE LAST KID LEFT A Novel Fiction, June 2017 (manuscript available) MCD/FSG Nineteen-year-old Nick Toussaint Jr. is driving drunk through New Jersey on his way to Mexico. The dead bodies of Toussaint’s doctor and his wife lie in the backseat. When Nick crashes the car, police chief Martin Krug becomes involved in the case. Despite an easy murder confession from Nick, something doesn’t quite add up for the soon-to-be retired Krug. An itch he can’t help but scratch. Nick is extradited to his hometown of Claymore, New Hampshire—a New England beach town full of colorful characters, bed-and-breakfasts, and outlet malls—where the local scandal rocks the residents. Meanwhile his girlfriend, sixteen-year-old Emily Portis, rallies behind her boyfriend, her protector. THE LAST KID LEFT charts the evolution of their relationship and of Emily’s own coming of age, in the face of tragedy and justice. Rosecrans Baldwin is the author of Paris, I Love You but You’re Bringing Me Down and You Lost Me There. He has written for GQ, The New York Times, the Los Angeles Times, and The Guardian. -

Fictional Displacements: an Analysis of Three Texts by Orhan Pamuk

Fictional Displacements: An Analysis of Three Texts by Orhan Pamuk Hande Gurses A Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the PhD Degree at UCL June 2012 I, Hande Gurses confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. 2 To my parents Didem & Haluk Gurses 3 Abstract This study aims to discuss the structural and contextual configuration of three books by Orhan Pamuk: The White Castle, My Name is Red and Istanbul: Memories of a City. The central line of enquiry will be the possibility of representing identity as the attempt to capture the elements that make the ‘self’ what it is. Without limiting my analysis to an individual or national definition of identity, I will argue that Pamuk, writing through the various metaphysical binaries including self/other, East/West, word/image, reality/fiction, and original/imitation, offers an alternative view of identity resulting from the definition of representation as différance. I will argue that within the framework of Pamuk’s work representation, far from offering a comforting resolution, is a space governed by ambivalence that results from the fluctuations of meaning. Representation, for Pamuk, is only possible as a process of constant displacement that enables meaning through difference and deferral. Accordingly the representation of identity is no longer limited to the binaries of the metaphysical tradition, which operate within firm boundaries, but manifests itself in constant fluctuation as ambivalence. Within this framework I will suggest that Pamuk’s works operate in that space of ambivalence, undermining the firm grounds of metaphysics by perpetually displacing any possibility of closure. -

So Long Lives This...And Gives Life to Thee

...and gives life to thee So long lives this... The Walrus 2017 Vol. 51 Saint Mary’s Hall San Antonio, Texas so long lives this Ars longa vita brevis. Man has long sought the secret to immortality. Try as he might to discover it, the closest man has ever come to eternity is through art and poetry. As long as our thoughts and ideas live in images and in words, our memory persists. How does art reflect your existence? The Walrus 2017, Vol. 51 Saint Mary’s Hall San Antonio, Texas But thy eternal summer shall not fade Nor lose possession of that fair thou ow’st; Nor shall Death brag thou wander’st in his shade, When in eternal lines to time thou grow’st; So long as men can breathe or eyes can see, So long lives this, and this gives life to thee. —William Shakespeare, Sonnet 18 Cover Art and Title Page Art, Moth, Watercolor by Alex Sugg (12) The Walrus 1 Alex Sugg Watercolor Moth Cover Mary Caroline Cavazos Ink and Gouache 13 Ways of Looking at a 50-51 Peyton Locke Mixed Media Element 3 Blackbird Madison Ross Acrylic Peyton 3 Isaac Goldstone Personal Narrative “The Mourning Process of a 51-52 Madison Ross Acrylic Lily 3 Rolex GMT” Alex Sugg Watercolor Torso 4-5 Margaret Shetler Ceramic & Gold Leaf Weight of the World 53 McLean Carrington Color Pencil A Rush 6 Amy Delano, Alexandra Lang, French Sonnet “À Mon Fils” 53 McLean Carrington Color Pencil A Push 7 Catie Sassoli Mary Caroline Cavazos Prose Poem “Flammable” 7 Michael Casey Haikus “Sad and Joy” 54 Laura Kayata Digital Photograph Old San Antonio 8 Margaret Booke Digital Photograph Fluorescent -

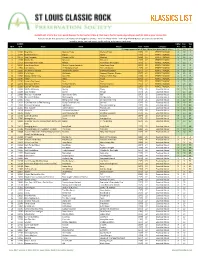

KLASSICS LIST Criteria

KLASSICS LIST criteria: 8 or more points (two per fan list, two for U-Man A-Z list, two to five for Top 95, depending on quartile); 1984 or prior release date Sources: ten fan lists (online and otherwise; see last page for details) + 2011-12 U-Man A-Z list + 2014 Top 95 KSHE Klassics (as voted on by listeners) sorted by points, Fan Lists count, Top 95 ranking, artist name, track name SLCRPS UMan Fan Top ID # ID # Track Artist Album Year Points Category A-Z Lists 95 35 songs appeared on all lists, these have green count info >> X 10 n 1 12404 Blue Mist Mama's Pride Mama's Pride 1975 27 PERFECT KLASSIC X 10 1 2 12299 Dead And Gone Gypsy Gypsy 1970 27 PERFECT KLASSIC X 10 2 3 11672 Two Hangmen Mason Proffit Wanted 1969 27 PERFECT KLASSIC X 10 5 4 11578 Movin' On Missouri Missouri 1977 27 PERFECT KLASSIC X 10 6 5 11717 Remember the Future Nektar Remember the Future 1973 27 PERFECT KLASSIC X 10 7 6 10024 Lake Shore Drive Aliotta Haynes Jeremiah Lake Shore Drive 1971 27 PERFECT KLASSIC X 10 9 7 11654 Last Illusion J.F. Murphy & Salt The Last Illusion 1973 27 PERFECT KLASSIC X 10 12 8 13195 The Martian Boogie Brownsville Station Brownsville Station 1977 27 PERFECT KLASSIC X 10 13 9 13202 Fly At Night Chilliwack Dreams, Dreams, Dreams 1977 27 PERFECT KLASSIC X 10 14 10 11696 Mama Let Him Play Doucette Mama Let Him Play 1978 27 PERFECT KLASSIC X 10 15 11 11547 Tower Angel Angel 1975 27 PERFECT KLASSIC X 10 19 12 11730 From A Dry Camel Dust Dust 1971 27 PERFECT KLASSIC X 10 20 13 12131 Rosewood Bitters Michael Stanley Michael Stanley 1972 27 PERFECT -

Dream Theater Octavarium Sheet Music

Dream Theater Octavarium Sheet Music Download dream theater octavarium sheet music pdf now available in our library. We give you 6 pages partial preview of dream theater octavarium sheet music that you can try for free. This music notes has been read 11716 times and last read at 2021-09-30 18:24:53. In order to continue read the entire sheet music of dream theater octavarium you need to signup, download music sheet notes in pdf format also available for offline reading. Instrument: Drum Set, Percussion Ensemble: Mixed Level: Advanced [ READ SHEET MUSIC ] Other Sheet Music Dream Theater Lifting Shadows Off A Dream Dream Theater Lifting Shadows Off A Dream sheet music has been read 3620 times. Dream theater lifting shadows off a dream arrangement is for Advanced level. The music notes has 3 preview and last read at 2021-09-30 18:19:42. [ Read More ] Dream Theater Another Day Dream Theater Another Day sheet music has been read 6205 times. Dream theater another day arrangement is for Advanced level. The music notes has 2 preview and last read at 2021-09-30 18:28:59. [ Read More ] Dream Theater As I Am Dream Theater As I Am sheet music has been read 6887 times. Dream theater as i am arrangement is for Advanced level. The music notes has 4 preview and last read at 2021-09-28 23:15:42. [ Read More ] Dream Theater Surrounded Dream Theater Surrounded sheet music has been read 4533 times. Dream theater surrounded arrangement is for Advanced level. The music notes has 2 preview and last read at 2021-09-29 12:19:37. -

Personality FOLIOS and Dvds

personalityFOLIOS and DVDs 6 PERSONALITY FOLIOS & DVDS Alfred’s Classic Album Editions Songbooks of the legendary recordings that defi ned and shaped rock and roll! Alfred’s Classic Album Editions Alfred’s Boston Michael Jackson Boston Thriller Titles: More Than a Feeling • Peace of Mind • Foreplay / Long Time • Rock & Roll Band • Titles: Baby Be Mine • Beat It • Billie Jean • The Girl Is Mine • Human Nature • The Lady in My Smokin’ • Hitch a Ride • Something About You • Let Me Take You Home Tonight. Life • P.Y.T. (Pretty Young Thing) • Thriller • Wanna Be Startin’ Somethin’ • Muscles. Authentic Guitar TAB ..............$19.95 00-27651 ____ Piano/Vocal/Chords ...............$16.95 00-25944 ____ UPC: 038081300658 ISBN-10: 0-7390-4557-1 ISBN-13: 978-0-7390-4557-2 UPC: 038081281803 ISBN-10: 0-7390-4257-2 ISBN-13: 978-0-7390-4257-1 Eagles Led Zeppelin Desperado Houses of the Holy Titles: Bitter Creek • Certain Kind of Fool • Chug All Night • Desperado • Desperado Part II • Titles: The Song Remains the Same • The Rain Song • Over the Hills and Far Away • The Doolin-Dalton • Doolin-Dalton Part II • Earlybird • Most of Us Are Sad • Nightingale • Out of Crunge • Dancing Days • D’Yer Mak’er • No Quarter • The Ocean. Control • Outlaw Man • Peaceful Easy Feeling • Saturday Night • Take It Easy • Take the Devil • Authentic Guitar TAB ..............$24.95 00-GF0524A ____ Tequila Sunrise • Train Leaves Here This Mornin’ • Tryin’ Twenty One • Witchy Woman. UPC: 038081305899 ISBN-10: 0-7390-4698-5 ISBN-13: 978-0-7390-4698-2 Piano/Vocal/Chords ...............$16.95 00-25945 ____ Led Zeppelin I UPC: 038081281810 ISBN-10: 0-7390-4258-0 ISBN-13: 978-0-7390-4258-8 Titles: Good Times Bad Times • Babe I’m Gonna Leave You • You Shook Me • Dazed and Hotel California Confused • Your Time Is Gonna Come • Black Mountain Side • Communication Breakdown • I Titles: Hotel California • New Kid in Town • Life in the Fast Lane • Wasted Time • Wasted Time Can’t Quit You Baby • How Many More Times. -

The Moravian Night a Story Peter Handke; Translated from the German by Krishna Winston

Here I Am A Novel Jonathan Safran Foer A monumental new novel from the bestselling author of Everything Is Illuminated and Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close In the book of Genesis, when God calls out, “Abraham!” to order him to sacrifice his son Isaac, Abraham responds, “Here I am.” Later, when Isaac calls out, “My father!” to ask him why there is no animal to slaughter, Abraham responds, “Here I am.” How do we fulfill our conflicting duties as father, husband, and son; wife and mother; child and adult? Jew and American? How can we claim our own identities when our lives are linked so closely to others’? These are FICTION the questions at the heart of Jonathan Safran Foer’s first novel in eleven years--a work of extraordinary scope and heartbreaking intimacy. Farrar, Straus and Giroux | 9/6/2016 9780374280024 | $28.00 / $31.50 Can. Unfolding over four tumultuous weeks, in present-day Washington, D.C., Hardcover | 592 pages Carton Qty: 0 | 9 in H | 6 in W Here I Am is the story of a fracturing family in a moment of crisis. As Brit., trans., 1st ser., dram.: Aragi, Inc. Jacob and Julia and their three sons are forced to confront the distances Audio: FSG between the lives they think they want and the lives they are living, a catastrophic earthquake sets in motion a quickly escalating conflict in the MARKETING Middle East. At stake is the very meaning of home--and the fundamental question of how much life one can bear. Author Tour National Publicity National Advertising Showcasing the same high-energy inventiveness, hilarious irreverence, Web Marketing Campaign and emotional urgency that readers and critics loved in his earlier work, Library Marketing Campaign Reading Group Guide Here I Am is Foer’s most searching, hard-hitting, and grandly entertaining Advance Reader's Edition novel yet. -

Dream Theater Celebrate 20Th Anniversary of 'Metropolis Pt. 2' Hit

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Contact: Christian Ross 901-652-1602 [email protected] David Beckwith 323-632-3277 [email protected] Dream Theater Celebrate 20th Anniversary of ‘Metropolis Pt. 2’ Hit Album, Brings ‘Distance Over Time Tour,’ to Soundstage at Graceland Band will perform landmark album in its entirety alongside classic tracks and selections from their latest release Distance Over Time MEMPHIS, Tenn. (July 22, 2019) – Over their 30+ year career, progressive rockers Dream Theater have redefined hard rock and heavy metal - selling more than 15 million records worldwide along the way - and on October 18, 2019, the two-time GRAMMY® nominees will bring their “The Distance Over Time Tour – Celebrating 20 Years of Scenes From A Memory” to the Soundstage at Graceland. Since their early days performing as Majesty, the progressive metal pioneers—James LaBrie (Vocals), John Petrucci (Guitars), Jordan Rudess (Keyboards), John Myung (Bass), and Mike Mangini (Drums)— have shared a unique bond with one of the most passionate fan bases around the globe. Their chart- topping hits “Take the Time” and “Pull Me Under” served as an introduction to Dream Theater for the masses, and they remain fan-favorites today. The band has shown no signs of slowing down, as they recently released their critically acclaimed, 14th full-length album, Distance Over Time, and showcase a newfound creativity for Dream Theater while maintaining the elements that have garnered them devoted fans for more 30 years. Early access pre-sale tickets for Dream Theater’s October 18 show go on sale Thursday, July 25 at 10 a.m. CDT (11 a.m. -

Universitas Sam Ratulangi Fakultas Ilmu Budaya Manado 2013

PREPOSISI DALAM LIRIK LAGU ALBUM METROPOLIS KARYA DREAM THEATER JURNAL SKRIPSI Oleh RIZAL THOMAS 080912032 SASTRA INGGRIS UNIVERSITAS SAM RATULANGI FAKULTAS ILMU BUDAYA MANADO 2013 ABSTRACT This research entitled “Prepositions in the Lyrics of Metropolis Album by Dream Theater” is written to analyze and classify the form and the meaning of the prepositions that are used in that album. A preposition is a word that connects a noun or pronoun with a verb, adjective, or another noun or pronoun by indicating a relationship between the things for which they stand. The problems of this research are focused on what are the form and the meaning of prepositions that are found in the lyrics of Metropolis Album? The method used in this research is descriptive. The data of prepositions in this research were collected from the lyrics of Metropolis Album Part I and Part II by Dream Theater. The data of the prepositions found in the album are given number and wrote in the small cards. The result of this research shows that The Writer of the lyrics in this album used many prepositions to express meaning through the lyrics of his songs. The research used Quirk (1985) concept in analyzing the form of prepositions, whereas Curme (1986) concept is used in analyzing the meaning of prepositions found in the lyrics of the songs in the Metropolis Album. Key words: Prepositions, Songs : Dream Theater, Metropolis I. PENDAHULUAN Bahasa merupakan instrumen utama dalam berkomunikasi dan itu tidak dapat dipisahkan dari manusia. Bahasa digunakan untuk mengekspresikan perasaan, merespon fenomena, berbagi ide, dan juga kritik-mengkritik.