For Drinking Water

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 and 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak a Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 AND 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2007 Committee: Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Dr. John Makay Graduate Faculty Representative Dr. Ron E. Shields Dr. Don McQuarie © 2007 Bradley C. Klypchak All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Between 1984 and 1991, heavy metal became one of the most publicly popular and commercially successful rock music subgenres. The focus of this dissertation is to explore the following research questions: How did the subculture of heavy metal music between 1984 and 1991 evolve and what meanings can be derived from this ongoing process? How did the contextual circumstances surrounding heavy metal music during this period impact the performative choices exhibited by artists, and from a position of retrospection, what lasting significance does this particular era of heavy metal merit today? A textual analysis of metal- related materials fostered the development of themes relating to the selective choices made and performances enacted by metal artists. These themes were then considered in terms of gender, sexuality, race, and age constructions as well as the ongoing negotiations of the metal artist within multiple performative realms. Occurring at the juncture of art and commerce, heavy metal music is a purposeful construction. Metal musicians made performative choices for serving particular aims, be it fame, wealth, or art. These same individuals worked within a greater system of influence. Metal bands were the contracted employees of record labels whose own corporate aims needed to be recognized. -

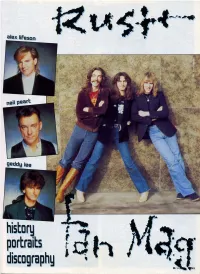

Rush Three of Them Decided to - Geddy Recieved a Phone Reform Rush but Without Call from Alex

history portraits J , • • • discography •M!.. ..45 I geddylee J bliss,s nth.slzers. vDcals neil pearl: percussion • alex liFesDn guitars. synt.hesizers plcs: Relay Photos Ltd (8); Mark Weiss (2); Tom Farrington (1): Georg Chin (1) called Gary Lee, generally the rhythm 'n' blues known as 'Geddy' be combo Ogilvie, who cause of his Polish/Jewish shortly afterwards also roots, and a bassist rarely changed their me to seen playing anything JUdd, splitting up in Sep other than a Yardbirds bass tember of the sa'l1le year. line. John and Alex, w. 0 were In September of the same in Hadrian, contacted year The Projection had Geddy again, and the renamed themselves Rush three of them decided to - Geddy recieved a phone reform Rush but without call from Alex. who was in Lindy Young, who had deep trouble. Jeff Jones started his niversity was nowhere to be found, course by then. In Autumn although a gig was 1969 the first Led Zeppelin planned for that evening. LP was released, and it hit Because the band badly Alex, Geddy an(i John like needed the money, Geddy a hammer. Rush shut them helped them out, not just selves away in their rehe providing his amp, but also arsal rooms, tUfned up the jumping in at short notice amp and discovered the to play bass and sing. He fascination of heavy was familiar with the Rush metaL. set alreadY, as they only The following months played well-known cover were going toJprove tough versions, and with his high for the three fYoung musi voice reminiscent of Ro cians who were either still bert Plant, he comple at school or at work. -

Orpe=Civ= V=Kfdeq Italic Flybynightitalic.Ttf

Examples Rush Font Name Rush File Name Album Element Notes Working Man WorkingMan.ttf Rush Logo, Album/Song RUSH Working Man Titles Fly By Night, regular and FlyByNightregular.ttf. orpe=civ=_v=kfdeq italic FlyByNightitalic.ttf Caress Of Steel CaressOfSteel.ttf Rush Logo, Album Title Need to Photoshop to get the correct style RUSH CARESS OF STEEL Syrinx Syrinx.ttf Rush Logo, Album/Song RUSH 2112 Titles ALL THE WORLD'S A STAGE (core font: Arial/Helvetica) Cover text Arial or Helvetica are core fonts for both Windows and Mac Farewell To Kings FarewellToKings.ttf Rush Logo, Album/Song Rush A Farewell To Kings Titles Strangiato Strangiato.ttf Rush Logo Similar to illustrated "Rush" Rush Hemispheres Hemispheres.ttf Album Title Custom font by Dave Ward. Includes special character for "Rush". Hemispheres | RUSH THROUGH TIME RushThroughTime RushThroughTime.ttf Album Title RUSH Jacob's Ladder JacobsLadder.ttf Rush Logo Hybrid font PermanentWaves PermanentWaves.ttf Album Title permanent waves Moving Pictures MovingPictures.ttf Rush Logo, Album Title Same font used for Archives, Permanent Waves general text, RUSH MOVING PICTURES Moving Pictures and Different Stages Exit...Stage Left Bold ExitStageLeftBold.ttf Rush Logo RUSH Exit...Stage Left ExitStageLeft.ttf Album Title Exit...Stage Left SIGNALS (core font: Garamond) Album Title Garamond, a core font in Windows and Mac Grace Under Pressure GraceUnderPressure.ttf Rush Logo, Album Title, Upper Case character set only RUSH GRACE UNDER PRESSURE Song Titles RUSH Grand Designs GrandDesigns.ttf Rush Logo RUSH Grand Designs Lined GrandDesignsLined.ttf Alternate version Best used at 24pt or larger Power Windows PowerWindows.ttf Album Title, Song Titles POWER WINDOWS Hold Your Fire Black HoldYourFireBlack.ttf Rush Logo Need to Photoshop to get the correct style RUSH Hold Your Fire HoldYourFire.ttf Album Title, Song Titles HOLD YOUR FIRE A Show Of Hands AShowofHands.ttf Song Titles Same font as Power Windows. -

Focus Group 7/26/10 1 FOCUS GROUP for the CITY of NEW BERLIN CITY CENTER JULY 26, 2010 Ted Wysocki, Alderman District 2 Welcome

Focus Group 7/26/10 FOCUS GROUP FOR THE CITY OF NEW BERLIN CITY CENTER JULY 26, 2010 Ted Wysocki, Alderman District 2 welcomed everyone to the Focus Group gathering. Carolyn Esswein and Mark Smith, GRAEF gave a power point presentation which can be found on the City’s website www.newberlin.org . Ms. Esswein asked for questions or comments: Ms. Esswein - How many use the library once a month? A show of hands indicated a few people did. Ms. Esswein - Do you use any of the other businesses in the area? A show of hands indicated a few people did. Ms. Esswein - Are you using services located throughout the entire City Center like where the new Sendik’s is going in, where the Walmart is? Focus Group Comment - Pick ‘n Save, Super Cuts, Subway, Dry Cleaner, Chinese Restaurant, Chumley’s Pub, Print Shop, Bank, Walmart, Hirschloffs, Great Wraps, Vision Cener, Dentist were places mentioned as places or services used in City Center. Sit down, white tablecloth restaurants where someone could entertain a client was indicated as something desired in City Center. Parking and Traffic Ms. Esswein - What is it you like about the area around the library? Is it easy to park when you go to Walmart or Pick ‘n Save? Focus Group Comment – Yes, it is very easy to park. Ms. Esswein – Is it easy to park in the area by Sendik’s? Focus Group Comment – Yes, it is easy to park. Ms. Esswein – Is it easy to park in the area by Great Wraps? Focus Group Comment – No. -

A Tribute to Rush's Incomparable Drum Icon

A TRIBUTE TO RUSH’S INCOMPARABLE DRUM ICON THE WORLD’S #1 DRUM RESOURCE MAY 2020 ©2020 Drum Workshop, Inc. All Rights Reserved. From each and every one of us at DW, we’d simply like to say thank you. Thank you for the artistry. Thank you for the boundless inspiration. And most of all, thank you for the friendship. You will forever be in our hearts. Volume 44 • Number 5 CONTENTS Cover photo by Sayre Berman ON THE COVER 34 NEIL PEART MD pays tribute to the man who gave us inspiration, joy, pride, direction, and so very much more. 36 NEIL ON RECORD 70 STYLE AND ANALYSIS: 44 THE EVOLUTION OF A LIVE RIG THE DEEP CUTS 48 NEIL PEART, WRITER 74 FIRST PERSON: 52 REMEMBERING NEIL NEIL ON “MALIGNANT NARCISSISM” 26 UP AND COMING: JOSHUA HUMLIE OF WE THREE 28 WHAT DO YOU KNOW ABOUT…CERRONE? The drummer’s musical skills are outweighed only by his ambitions, Since the 1970s he’s sold more than 30 million records, and his playing which include exploring a real-time multi-instrumental approach. and recording techniques infl uenced numerous dance and electronic by Mike Haid music artists. by Martin Patmos LESSONS DEPARTMENTS 76 BASICS 4 AN EDITOR’S OVERVIEW “Rhythm Basics” Expanded, Part 3 by Andy Shoniker In His Image by Adam Budofsky 78 ROCK ’N’ JAZZ CLINIC 6 READERS’ PLATFORM Percussion Playing for Drummers, Part 2 by Damon Grant and Marcos Torres A Life Changed Forever 8 OUT NOW EQUIPMENT Patrick Hallahan on Vanessa Carlton’s Love Is an Art 12 PRODUCT CLOSE-UP 10 ON TOUR WFLIII Three-Piece Drumset and 20 IN THE STUDIO Peter Anderson with the Ocean Blue Matching Snare Drummer/Producer Elton Charles Doc Sweeney Classic Collection 84 CRITIQUE Snares 80 NEW AND NOTABLE Sabian AAX Brilliant Thin Crashes 88 BACK THROUGH THE STACK and Ride and 14" Medium Hi-Hats Billy Cobham, August–September 1979 Gibraltar GSSVR Stealth Side V Rack AN EDITOR’S OVERVIEW In His Image Founder Ronald Spagnardi 1943–2003 ole models are a tricky thing. -

Foreword 5 Introduction 6 About This Book 8 the Making of Taking Center Stage 14 Drum Key 30

TAKING CENTER STAGE a lifetime of live performance NEIL PEART by Joe Bergamini © 2012 Hudson Music LLC International Copyright Secured. All Rights Reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher. www.hudsonmusic.com ConTenTsConTenTsConTenTs Foreword 5 Introduction 6 About This Book 8 The Making of Taking Center Stage 14 Drum Key 30 CHAPTER 1: 2112 and All the World’s a Stage Tours (1976-77) 33 Drum Setup 35 CHAPTER 2: A Farewell to Kings Tour (1977) 36 Drum Setup 39 CHAPTER 3: Hemispheres Tour (1978-79) 40 Drum Setup 42 ”The Trees” 43 Analysis 43 Drum Transcription 45 “La Villa Strangiato” 49 Analysis 49 Drum Transcription 51 CHAPTER 4: Permanent Waves Tour (1979-80) 58 Drum Setup 60 ”The Spirit of Radio” 61 Analysis 61 Drum Transcription 62 ”Free Will” 66 Analysis 66 Drum Transcription 68 ”Natural Science” 73 Analysis 73 Drum Transcription 75 CHAPTER 5: Moving Pictures Tour (1980-81) 81 Drum Setup 84 ”Tom Sawyer” 85 Analysis 85 Drum Transcription 87 ”YYZ” 91 Analysis 91 Drum Transcription 93 CHAPTER 6: Signals Tour (1982-83) 97 Drum Setup 101 ”Subdivisions” 102 Analysis 102 Drum Transcription 104 CHAPTER 7: Grace Under Pressure and Power Windows Tours (1984-86) 108 Drum Setup 113 ”Marathon” 114 Analysis 115 Drum Transcription 116 2 CHAPTER 8: Hold Your Fire Tour (1987-88) 122 Drum Setup 126 ”Time Stand Still” 128 Analysis 128 Drum Transcription 129 CHAPTER 9: Presto Tour (1990) 134 Drum Setup 136 ”Presto” 138 Analysis 138 Drum Transcription 140 CHAPTER -

Concerts for Kids

Concerts for Kids Study Guide 2014-15 San Francisco Symphony Davies Symphony Hall study guide cover 1415_study guide 1415 9/29/14 11:41 AM Page 2 Children’s Concerts – “Play Me A Story!” Donato Cabrera, conductor January 26, 27, 28, & 30 (10:00am and 11:30am) Rossini/Overture to The Thieving Magpie (excerpt) Prokofiev/Excerpts from Peter and the Wolf Rimsky-Korsakov/Flight of the Bumblebee Respighi/The Hen Bizet/The Doll and The Ball from Children’s Games Ravel/Conversations of Beauty and the Beast from Mother Goose Prokofiev/The Procession to the Zoo from Peter and the Wolf Youth Concerts – “Music Talks!” Edwin Outwater, conductor December 3 (11:30am) December 4 & 5 (10:00am and 11:30am) Mussorgsky/The Hut on Fowl’s Legs from Pictures at an Exhibition Strauss/Till Eulenspiegel’s Merry Pranks (excerpt) Tchaikovsky/Odette and the Prince from Swan Lake Kvistad/Gending Bali for Percussion Grieg/In the Hall of the Mountain King from Peer Gynt Britten/Storm from Peter Grimes Stravinsky/Finale from The Firebird San Francisco Symphony children’s concerts are permanently endowed in honor of Mrs. Walter A. Haas. Additional support is provided by the Mimi and Peter Haas Fund, the James C. Hormel & Michael P. NguyenConcerts for Kids Endowment Fund, Tony Trousset & Erin Kelley, and Mrs. Milton Wilson, together with a gift from Mrs. Reuben W. Hills. We are also grateful to the many individual donors who help make this program possible. San Francisco Symphony music education programs receive generous support from the Hewlett Foundation Fund for Education, the William Randolph Hearst Endowment Fund, the Agnes Albert Youth Music Education Fund, the William and Gretchen Kimball Education Fund, the Sandy and Paul Otellini Education Endowment Fund, The Steinberg Family Education Endowed Fund, the Jon and Linda Gruber Education Fund, the Hurlbut-Johnson Fund, and the Howard Skinner Fund. -

June 18, 2012 Workshop Minutes

SUMMARY OF THE WORKSHOP TO SOLICIT COMMENTS ON THE PROPOSED REGULATIONS OF THE PERSONNEL COMMISSION THROUGH THE DIVISION OF HUMAN RESOURCE MANAGEMENT June 18, 2012 CARSON CITY, NEVADA And via Video Conferencing in LAS VEGAS, NEVADA Attendees in Carson City: Shelley Blotter, Deputy Administrator, Division of Human Resource Management Peter Long, Deputy Administrator, Division of Human Resource Management Mark Evans, Division of Human Resource Management Kimberley King, Personnel Officer III, Department of Transportation Sheri Vondrak, NDOT Tracy Walters, NDOT Adam Drost, Central Payroll Manager, DHRM Alys Dobel, Personnel Officer III, DMV Teri Hack, Forestry Denise Woo-Seymour, DHRM Carrie Hughes, DHRM Mary Gordon, DHCFP Denise Madole, UNR Janet Damschen, UNR Maureen Martinez, Risk Management Kareen Masters, Deputy Director, DHHS Angelica Gonzalez, DHRM Amy Davey, DHRM Carrie Parker, Attorney General’s Office Mindy McKay, DPS Kateri Cavin, PEBP Roger Rahming, PEBP Jim Wells, Executive Officer, PEBP Chrissy Miller, Records Cynthia Willden, Records Anke Simpson, State Parks Renee Travis, DHHS Michelle Barnes, MHDS Norma Mallett, MHDS Priscilla Maloney, AFSCME Local 4041 Lauren Risinger DCFS Ashu Manocha, DMV Hazel Brandon, DMV Attendees in Las Vegas: Willette Gerald, DMV-HR Michelle Hooper, CSN Naomi Thomsen, UNLV Johnny Hanes, UNLV Larry Hamilton, Chief Human Resources Officer, UNLV John Scarborough, CSN Karen Belleni, DETR Heather Dapice, DHRM-CCR Call to Order: Shelley Blotter: Opened the meeting at 9:05 a.m. and explained that initially the participants would be surveyed to determine which regulations were going to receive either support or objections before discussing the individual regulation changes. The proposed regulation changes are part of the review process that the Governor asked all agencies to undertake with an objective of simplification, consistency, and making the regulations easier for our customers to deal with. -

Moving Pictures Pdf, Epub, Ebook

MOVING PICTURES PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Terry Pratchett | 400 pages | 16 Jun 2008 | Transworld Publishers Ltd | 9780552134637 | Spanish | London, United Kingdom Moving Pictures PDF Book Stage Left , discussed the various people on the Moving Pictures cover. Progressive rock. Music Videos Show us your Rush. Rush - 'Moving Pictures ' ". I needed to think last night. Newsletter In October their second album, Matinee , also produced by Fisher, was released. Archived from the original on 15 April Moving Pictures are an Australian rock music band formed in Archived from the original on February 1, AUS: 3x Platinum [30]. Retrieved February 20, Character Profile. February So what does Ren McCormack punch-dance to when he needs to left off some steam in the year ? Leland Stanford of California, a zealous racehorse breeder, to prove that at some point in its gallop a running horse lifts all four hooves off the ground at once. Select albums in the Format field. Retrieved August 21, Credits are adapted from the album's liner note. Before the invention of photography, a variety of optical toys exploited this effect by mounting successive phase drawings of things in motion on the face of a twirling disk the phenakistoscope , c. Awards Canadian Albums Chart 1. The Sunday Telegraph. In June , the band ended their ten- month tour of the United States, Canada and the United Kingdom in support of their seventh studio album, Permanent Waves The song made an unusual comeback in , peaking at No. Rush Terry Brown. Retrieved May 1, Archived from the original on June 10, Archived from the original on 23 July Hung Medien. -

The Vapor Trail February 2019

The Vapor Trail February 2019 Vapor Trail Vettes, P.O. Box 5241, Santa Maria, CA 93456 www.vaportrailvettes.com Inside this Issue President’s Message By Clay Beck Presidents Message/Birthdays 1 Meeting Minutes 2 Hello Members, Run to Charlies Burgers 3 Well we have had quite a wet winter this Regional Gov. Meeting Minutes 4 year. I’m confident we will have some sunny days soon because we live in sunny California VTV VP Proposed Meetings/Runs 5 right. So get some wax on those Vettes Tech Corner 6-8 the street will be dry soon. For Sale/Business Cards 9 Our VP Holly has been planning some runs for this VTV Sponsor/Corvette Inventory 10 year. She has sent out an email with several se- Calendar of Events 11-13 lections on what to do and she is asking for mem- bers to help by voting on your favorites. Our first Event Flyers 14-15 run is being planned to Reagan’s library on March 30th. February 2019 Birthday We had our first meeting of the year and was able 01 Chris Deviny to approve our budget. I want to thank our treasurer Chuck Robertson for putting it all to- March 2019 Birthday gether. We are also planning 4 autocross event 03 Kathy Beck this year. The first one being March 23. 07 Larry Wright We will see you at our next meet March 7th. 12 Bill Deviny Later, Clay 13 Bill Santmyer 27 Pamela Wright 31 Jeff Palmer UPCOMING IN MARCH 2019 Board Members President Clay Beck 481-4597 Vice President Holly Palmer 588-0246 Treasurer Chuck Robertson 934-0694 Secretary Beverly Erickson 941-786-6575 Governor: Gale Haugen 773-4515 Newsletter Gale Haugen 773-4515 Sunshine Lady Brenda Parks 315-0070 Webmaster Chuck Robertson 934-0694 1 February 7, 2019 VTV Meeting February 7, 2019 VTV Meeting Minutes Minutes By Chuck Robertson/Beverly Erickson By Chuck Robertson/Beverly Erickson In attendance: Larry Wright, Jeff & Holly Palmer, Hal Vice President Report – Holly Palmer and Paula Malone, Breda Parks, Gerry White, Cliff & Holly then started a discussion on events for the year. -

AGENDA Planning and Zoning Commission Meeting 4:30 PM Tuesday, June 1, 2021

City of Sedona AGENDA Planning and Zoning Commission Meeting 4:30 PM Tuesday, June 1, 2021 NOTICE: Due to continued precautions related to the COVID-19 pandemic, there will be Pursuant to A.R.S. 38-431.02 notice is very limited seating for the public within the Council Chambers arranged in hereby given to the members of the Planning and Zoning Commission and compliance with CDC guidelines for physical distancing. Comments in advance to the general public that the of the 4:30 p.m. call to order are strongly encouraged by sending an email to Planning and Zoning Commission will [email protected] and will be made part of the official meeting record. hold a work session open to the Those wishing to comment on scheduled agenda items may be asked to wait public on Tuesday, June 1, 2021 at outdoors or in an alternate location if there is not adequate seating in Council 4:30 pm in the City Hall Council Chambers. Chambers. The meeting can be viewed live on the City’s website at www.sedonaaz.gov or on cable Channel 4. NOTES: • Meeting room is wheelchair 1. CALL TO ORDER, PLEDGE OF ALLEGIENCE, ROLL CALL accessible. American Disabilities 2. ANNOUNCEMENTS & SUMMARY OF CURRENT EVENTS BY COMMISSIONERS & Act (ADA) accommodations are available upon request. Please STAFF phone 928-282-3113 at least 24 (This is the time for the public to comment on matters not hours in advance. 3. PUBLIC FORUM: • Planning & Zoning Commission listed on the agenda. The Commission may not discuss items that are not Meeting Agenda Packets are specifically identified on the agenda. -

UDLS: Friday, Sept 23, 2011 Murray Patterson What You See

UDLS: Friday, Sept 23, 2011 Murray Patterson What you see... I typical 70's band (formed in 1968 actually) I solid, timeless rock band { one of their initial inspirations: Led Zeppelin (example: What You're Doing) I well-known songs include: Limelight, Tom Sawyer, (maybe 2112, Subdivisions) What you see... I typical 70's band (formed in 1968 actually) I solid, timeless rock band { one of their initial inspirations: Led Zeppelin (example: What You're Doing) I well-known songs include: Limelight, Tom Sawyer, (maybe 2112, Subdivisions) In Pop Culture I some pretty weird dudes: sort of nerdy, outcast I lyrics: Subdivisions, The Body Electric I tour with Kiss (interview with Gene Simmons) I not mainstream, but has a huge cult following: quoted as \the most successful cult band next to Kiss" I featured in: Family Guy, South Park, Futurama, an episode of Trailer Park Boys, and in the movie \I Love you Man" I great documentary on the band { Rush: Beyond the Lighted Stage Wikipedia Sez: Rush is a Canadian rock band formed in August 1968, in the Willowdale neighbourhood of Toronto, Ontario. The band is composed of bassist, keyboardist, and lead vocalist Geddy Lee, guitarist Alex Lifeson, and drummer and lyricist Neil Peart. The band and its membership went through a number of re-configurations between 1968 and 1974, achieving their current form when Peart replaced original drummer John Rutsey in July 1974, two weeks before the group's first United States tour. Since the release of the band's self-titled debut album in March 1974, Rush has become known for its musicianship, complex compositions, and eclectic lyrical motifs drawing heavily on science fiction, fantasy, and philosophy, as well as addressing humanitarian, social, emotional, and environmental concerns.