Imagining Global Video: the Challenge of Netflix in FOCUS

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Organisational Structure, Programme Production and Audience

OBSERVATOIRE EUROPÉEN DE L'AUDIOVISUEL EUROPEAN AUDIOVISUAL OBSERVATORY EUROPÄISCHE AUDIOVISUELLE INFORMATIONSSTELLE http://www.obs.coe.int TELEVISION IN THE RUSSIAN FEDERATION: ORGANISATIONAL STRUCTURE, PROGRAMME PRODUCTION AND AUDIENCE March 2006 This report was prepared by Internews Russia for the European Audiovisual Observatory based on sources current as of December 2005. Authors: Anna Kachkaeva Ilya Kiriya Grigory Libergal Edited by Manana Aslamazyan and Gillian McCormack Media Law Consultant: Andrei Richter The analyses expressed in this report are the authors’ own opinions and cannot in any way be considered as representing the point of view of the European Audiovisual Observatory, its members and the Council of Europe. CONTENT INTRODUCTION ...........................................................................................................................................6 1. INSTITUTIONAL FRAMEWORK........................................................................................................13 1.1. LEGISLATION ....................................................................................................................................13 1.1.1. Key Media Legislation and Its Problems .......................................................................... 13 1.1.2. Advertising ....................................................................................................................... 22 1.1.3. Copyright and Related Rights ......................................................................................... -

Spanish Films and Series on NETFLIX

Spanish Films and Series on NETFLIX Watching a Spanish film or programme on Netflix is a great way of learning a language as you can be immersed in the language while familiarising yourself with Hispanic and Latino culture and customs. Language learning should always be fun, as enjoyment plays a big role in keeping you motivated. So, why don’t you watch a few of the films on this list and make your learning entertaining! Features on Netflix for Language Learning Subtitles: There are different options available on Netflix depending on your level. You can watch Spanish films or programmes with English subtitles first, and then watch them again with Spanish subtitles. When you’re more confident, you can watch films without subtitles altogether. Audio description: Another great feature on Netflix for learning Spanish is the audio description feature, which exists for some but not all shows. This feature allows you to hear what you see, in Spanish, which improves comprehension and also boosts your vocabulary. It is an intense but fruitful way to immerse yourself in a language. Films on Netflix Date I What I thought of it… watched it 1 Roma 2 Holy Camp (La Llamada) 3 Like water for chocolate (Como agaua para chocolate) 4 Spanish Affair 2 (Ocho Apellidos Catalanes) 5 The Invisible Guest (Contratiempo) 6 The Fury of an Innocent man (Tarde para la Ira) 7 Zipe & Zape y la Isla del capitán 8 Smoke and Mirrors (El hombre de las mil caras) 9 100 metres (100 metros) 10 Palmtrees in the snow (Palmeras en la nieve) 11 Holy Goalie 12 Thi Mai 1) Roma (2hrs 14 mins ) Oscar winner Alfonso Cuarón delivers a vivid, emotional portrait of a domestic worker’s journey set against domestic and political turmoil in 1970’s Mexico. -

Constructing, Programming, and Branding Celebrity on Reality Television

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Producing Reality Stardom: Constructing, Programming, and Branding Celebrity on Reality Television A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the Requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Film and Television by Lindsay Nicole Giggey 2017 © Copyright by Lindsay Nicole Giggey 2017 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Producing Reality Stardom: Constructing, Programming, and Branding Celebrity on Reality Television by Lindsay Nicole Giggey Doctor of Philosophy in Film and Television University of California, Los Angeles, 2017 Professor John T. Caldwell, Chair The popular preoccupation with celebrity in American culture in the past decade has been bolstered by a corresponding increase in the amount of reality programming across cable and broadcast networks that centers either on established celebrities or on celebrities in the making. This dissertation examines the questions: How is celebrity constructed, scheduled, and branded by networks, production companies, and individual participants, and how do the constructions and mechanisms of celebrity in reality programming change over time and because of time? I focus on the vocational and cultural work entailed in celebrity, the temporality of its production, and the notion of branding celebrity in reality television. Dissertation chapters will each focus on the kinds of work that characterize reality television production cultures at the network, production company, and individual level, with specific attention paid to programming focused ii on celebrity making and/or remaking. Celebrity is a cultural construct that tends to hide the complex labor processes that make it possible. This dissertation unpacks how celebrity status is the product of a great deal of seldom recognized work and calls attention to the hidden infrastructures that support the production, maintenance, and promotion of celebrity on reality television. -

The Evolution of the Concept of Public Service and the Transition in Spanish Television

Medij. istraž. (god. 15, br. 2) 2009. (49-70) IZVORNI ZNANSTVENI RAD UDK: 316.77(460):7.097 Primljeno: 30. listopada 2009. The Evolution of the Concept of Public Service and the Transition in Spanish Television Carmen Ciller Tenreiro* SUMMARY The paper examines the presence of the public interest in contemporary Span- ish television medium. For many years there was a solidly-held belief that there are important public assets (principally educational, cultural and de- mocratic) which could only be provided by public television. In recent years in Spain, after the Transition process, and with democracy having been consoli- dated, a new period of maturity in television, in which society itself demands and expects that television in general, both public and private, guarantees a series of values and public assets. In the first part, the author explains what are the origins of television in Spain: from what is the nature of public service and legislation that supports it (where are established the public interest criteria that must always prevail in the public television medium, and private television later) to the development and consolidation of the television system in Spain with the arrival of regional television, private television channels and pay television platforms. In the sec- ond part of the paper, the situation of the programme listings of general public and private television channels which operate in Spain is analyzed through the case study of the first week of March 2009. The study of prime time enables to know which are the most important genres of television programming in Spain and what television preserve the public interest. -

Q2 2020 Letter to Shareholders

July 16, 2020 Fellow shareholders, We live in uncertain times with restrictions on what we can do socially and many people are turning to entertainment for relaxation, connection, comfort and stimulation. In Q1 and Q2, we saw significant pull-forward of our underlying adoption leading to huge growth in the first half of this year (26 million paid net adds vs. prior year of 12 million). As a result, we expect less growth for the second half of 2020 compared to the prior year. As we navigate these turbulent circumstances, we’re focused on our members by continuing to improve the quality of our service and bringing new films and shows to people's screens. Our Q2 summary results and forecast for Q3 are in the table below. Ted Sarandos appointed co-CEO and elected to Board of Directors Ted joined Netflix over 20 years ago, and we are thrilled to appoint him to be co-CEO with Reed. “Ted has been my partner for decades. This change makes formal what was already informal -- that Ted and I share the leadership of Netflix,” says Hastings. Lead Independent director Jay Hoag says “Having watched Reed and Ted work together for so long, the board and I are confident this is the right step to evolve Netflix’s management structure so that we can continue to best serve our members and shareholders for years to come.” 1 Ted will also continue to serve as Chief Content Officer. In addition, Greg Peters has been appointed COO adding to his Chief Product Officer role. -

Jane the Virgin”

Culture, ethnicity, religion, and stereotyping in the American TV show “Jane the Virgin” Fares 2 Contents Introduction………………………………………………………………………..…………….….3 1. Theory & Methodology……………………………………………..………..……………….…4 2. Cultural theory……………………………………………………………..…………………….6 2.1 stereotypes and their Functions: ‘othering’, ‘alterity’, ‘us’ and ‘them’ dichotomy……………………………………………………………...…..…6 2.2 race and ethnicity………………….……..…………………….......….16 2.3 religion………………………………………………………………......18 2.4 virginity and ‘marianismo’..……………………………………….…...19 2.5 identity…………………….………………………...….……………….20 3. Media Context….…………………….……………………...…………………………………24 3.1 postmodernism and television..………………...………………..…24 3.2 Latin American soap operas…………………………………….…..27 3.3 American soap operas ………………………………………..….….31 4. Genre Analysis Context…….…………………………………………………………………33 4.1 genre theory and concepts...…………………………………..……34 4.2 comedy..………………………………………………………...….…38 5. Cultural Analysis oF “Jane The Virgin”……………………………………………………….42 6. Genre Analysis oF “Jane the Virgin”…………………………………………………….……61 7. Comparison & Discussion………………………………………………...…………….…….72 8. Conclusion…………………………………………………………………..………………….75 9. Works Cited…………………..……………………………………………..………………….77 Fares 3 Adalat Lena Fares Bent Sørensen Master’s Thesis 2. June 2020 Culture, ethnicity, religion, and stereotyping in the American TV show "Jane the Virgin" "Jane the Virgin" is an American television show on The CW, that parodies the Latin American soap opera format, while also depicting and handling real-life issues. The -

Literature Film & Course Description

CONTEMPORARY SPANISH LITERATURE FILM & COURSE DESCRIPTION This course presents the ideological and cultural shifts in Spain before, during, and after the Franco dictatorship through literature and film from the beginning of the 20th century to present day. In this [SPAN 403] course, we’ll situate the diverse country in its Fall 2020 | T &TH | 12:00-1:15 European and world contexts through a variety of literary works and film productions. We will continue R. Tyler Gabbard-Rocha developing critical thinking tools as a means of Email: [email protected] studying the human condition and familiarize Office: SC G003 ourselves with the literary and artistic styles, Office Hours: Tuesday 10:45- movements, periods, ideologies, and cultural 11:45; Friday 11:00- influences that produced these works in order to 12:00; or by appointment relate them to the current world at large. PREREQUISITES Students must have completed or be currently enrolled in Spanish VI. OBJECTIVES There are several outcomes for this course. You will learn to interpret and critically analyze Spanish literature and film as demonstrated by the following goals: 1. You will be able to recognize and identify influential works of literature and film representing the contemporary canon. 2. Furthermore, you will learn to analyze these works using the appropriate terminology as they relate to sociocultural, historical, and literary movements. 3. Finally, you will learn to compare these works in their own context and in European and world contexts today, including your own experiences. P a g e | 2 REQUIRED TEXTS All texts are available on Canvas. You will need to bring the correct text to class each day, either in print or electronically. -

The Netflix Effect: Teens, Binge Watching, and On-Demand Digital Media Trends

The Netflix Effect: Teens, Binge Watching, and On-Demand Digital Media Trends Sidneyeve Matrix Jeunesse: Young People, Texts, Cultures, Volume 6, Issue 1, Summer 2014, pp. 119-138 (Article) Published by The Centre for Research in Young People's Texts and Cultures, University of Winnipeg DOI: https://doi.org/10.1353/jeu.2014.0002 For additional information about this article https://muse.jhu.edu/article/553418 Access provided at 9 Jul 2019 13:25 GMT from University of Pittsburgh The Netflix Effect: Teens, Binge Watching, and On-Demand Digital Media Trends —Sidneyeve Matrix Introduction first time Netflix had released an entire season of an original program simultaneously and caused a Entertainment is fast becoming an all-you-can-eat nationwide video-on-demand stampede. When House buffet. Call it the Netflix effect. of Cards and Orange Is the New Black premiered in –Raju Mudhar, Toronto Star 2013, huge percentages of Netflix subscribers watched back-to-back episodes, devouring a season of content Whatever our televisual drug of choice—Battlestar in just days. Although these three shows belong to Galactica, The Wire, Homeland—we’ve all put different genres—one a sitcom and the others adult- off errands and bedtime to watch just one more, a themed melodramas—what they share is an enormous thrilling, draining, dream -influencing immersion popularity among the millennial cohort that makes up experience that has become the standard way to the majority of the subscriber base of Netflix. When consume certain TV programs. all episodes of a season -

Análisis Del Uso De Estrategias De Crecimiento En Netflix

UNIVERSIDAD MIGUEL HERNÁNDEZ FACULTAD DE CIENCIAS SOCIALES Y JURÍDICAS DE ELCHE GRADO EN ADMINISTRACIÓN Y DIRECCIÓN DE EMPRESAS ANÁLISIS DEL USO DE ESTRATEGIAS DE CRECIMIENTO EN NETFLIX. TRABAJO FIN DE GRADO. CURSO ACADÉMICO 2015/2016 Alumna: Emma Leticia Rufete Vicente. Tutora: Elena González Gascón. Resumen. El presente Trabajo Fin de Grado consiste en un estudio sobre el crecimiento de Netflix que es una empresa que presta un servicio de vídeo bajo demanda y está disponible en más de 190 países. En primer lugar se realiza un análisis externo e interno para describir el entorno en el que opera la empresa para establecer un diagnóstico de la situación y además se identifica la ventaja competitiva de la compañía. Netflix sigue una estrategia competitiva híbrida, basada en el liderazgo de costes y diferenciación del producto cuyo resultado es que la empresa se ha posicionado como líder mundial en suscriptores en su sector. Por otro lado, este trabajo explora la relación entre la estrategia y el crecimiento utilizando la matriz de Ansoff como marco de referencia. A continuación se aborda el principal problema de Netflix que está relacionado con la financiación de su expansión y por último se hacen recomendaciones sobre cómo mejorar el servicio. Palabras clave: estrategias de crecimiento, matriz de Ansoff, binge-watching, ventaja competitiva; expansión. Índice de contenidos. 1. INTRODUCCIÓN. .......................................................................................... 1 2. INFORMACIÓN GENERAL DE LA EMPRESA. ........................................... -

La Oportunidad De Las Series Españolas Con La Llegada De Las Plataformas De Vídeo Bajo Suscripción

MÁSTER EN MARKETING DIGITAL, COMUNICACIÓN Y REDES SOCIALES La oportunidad de las series españolas con la llegada de las plataformas de vídeo bajo suscripción Mayo 2020 MÁSTER EN MARKETING DIGITAL, COMUNICACIÓN Y REDES SOCIALES La oportunidad de las series españolas con la llegada de las plataformas de vídeo bajo suscripción Autora: María Giménez Cortés Tutor: Jorge Gallardo Camacho Máster Universitario en Marketing Digital, Comunicación y Redes Sociales. 1 ÍNDICE ÍNDICE ......................................................................................................................... 2 1. INTRODUCCIÓN ................................................................................................... 8 2. OBJETIVOS E HIPÓTESIS ................................................................................. 10 2.1. Objetivos ...................................................................................................... 10 2.2. Hipótesis ....................................................................................................... 10 3. METODOLOGÍA .................................................................................................. 11 3.1. Técnica cuantitativa ...................................................................................... 11 4. MARCO TEÓRICO .............................................................................................. 16 4.1. Televisión e Internet en España .................................................................... 16 4.1.1. El consumo audiovisual digital -

Mrts 4450/5660.001: It's Not Tv, It's Hbo!

MRTS 4450/5660.001: IT’S NOT TV, IT’S HBO! University of North Texas Fall 2020 Professor: Jennifer Porst Email: [email protected] Class: T 2:30-5:20P Office Hours: By appointment Course Description: Since its debut in the early 1970s, HBO has been a powerhouse in American television and film. They regularly dominate the nominations for Emmy and Golden Globe awards, and their success has profoundly affected the television and film industries and the content they produce. Through an examination of the birth and development of HBO, we will see what a closer analysis of the channel can tell us about television, Hollywood, and American culture over the last four decades. We will also look to the future to see what HBO might become in the increasingly global and digital television landscape. Student Learning Goals: This course will provide students with an opportunity to: • Understand the industrial conditions that led to the birth and success of HBO • Gain insight into the contemporary challenges and opportunities faced by the media industries • Develop critical thinking skills through focused analysis of readings and HBO content • Communicate clearly and confidently in class discussion and presentations Required Texts: 1. Edgerton, Gary R. and Jeffrey P. Jones, Eds. The Essential HBO Reader. Lexington, KY: The University Press of Kentucky, 2008. Available as an e-book via the UNT Library website. 2. Subscription to HBO Go/Now 3. Additional required readings and screenings will be available for free through the class website. 4. Students will need to register for use of the Packback Questions site, which should cost between $10- 15 for the semester. -

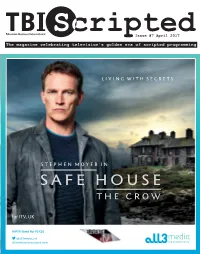

STEPHEN MOYER in for ITV, UK

Issue #7 April 2017 The magazine celebrating television’s golden era of scripted programming LIVING WITH SECRETS STEPHEN MOYER IN for ITV, UK MIPTV Stand No: P3.C10 @all3media_int all3mediainternational.com Scripted OFC Apr17.indd 2 13/03/2017 16:39 Banijay Rights presents… Provocative, intense and addictive, an epic retelling A riveting new drama series Filled with wit, lust and moral of the story of Versailles. Brand new second season. based on the acclaimed dilemmas, this five-part series Winner – TVFI Prix Export Fiction Award 2017. author Åsa Larsson’s tells the amazing true story of CANAL+ CREATION ORIGINALE best-selling crime novels. a notorious criminal barrister. Sinister events engulf a group of friends Ellen follows a difficult teenage girl trying A husband searches for the truth when A country pub singer has a chance meeting when they visit the abandoned Black to take control of her life in a world that his wife is the victim of a head-on with a wealthy city hotelier which triggers Lake ski resort, the scene of a horrific would rather ignore her. Winner – Best car collision. Was it an accident or a series of events that will change her life crime. Single Drama Broadcast Awards 2017. something far more sinister? forever. New second series in production. MIPTV Stand C20.A banijayrights.com Banijay_TBI_DRAMA_DPS_AW.inddScriptedpIFC-01 Banijay Apr17.indd 2 1 15/03/2017 12:57 15/03/2017 12:07 Banijay Rights presents… Provocative, intense and addictive, an epic retelling A riveting new drama series Filled with wit, lust and moral of the story of Versailles.