The Liberal State Versus Individual Rights

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

01.01.13 Green Liberalism

The Green liberalism project is part of a wider Green Alliance programme which looks at the relationship between the values and priorities of the UK’s three main political traditions – conservatism, liberalism and social democracy – and their support for the development of a greener economy. Green Alliance is non-partisan and supports a politically pluralist approach to greening the economy and restoring natural systems. Many political scientists consider the environment to be an issue similar to health and education where voters judge the likely competence of a party if it were in power, and where most voters want similar outcomes. In such issues parties tend to avoid taking sharply contrasting ‘pro’ or ‘anti’ positions.1 Nevertheless the way environmental outcomes are achieved, and even understood, will differ depending on how individual parties view the confluence of their values with environmental solutions. There is also a risk that as environmental policy beings to impinge on significant economic decisions, such as the transformation of transport and energy infrastructure, there will be less common ground between parties. The two-year Green Roots programme will work with advisory groups made up of independent experts and supporters of each political tradition, including parliamentarians, policy experts and academics, to explore how the UK’s main political traditions can address environmental risks and develop distinct responses which align with their values. Liberalism is founded on a supreme belief in the importance of the individual.2 This belief naturally extends to a commitment to individual freedom, supported by the argument that “human beings are rational, thinking creatures… capable of defining and pursuing their own best interests.”3 However, “liberals do not believe that a balanced and tolerant society will develop naturally out of the free actions of individuals.. -

The Political History of Nineteenth Century Portugal1

The Political History of Nineteenth Century Portugal1 Paulo Jorge Fernandes Autónoma University of Lisbon [email protected] Filipe Ribeiro de Meneses National University of Ireland [email protected] Manuel Baiôa CIDEHUS-University of Évora [email protected] Abstract The political history of nineteenth-century Portugal was, for a long time, a neglected subject. Under Salazar's New State it was passed over in favour of earlier periods from which that nationalist regime sought to draw inspiration; subsequent historians preferred to concentrate on social and economic developments to the detriment of the difficult evolution of Portuguese liberalism. This picture is changing, thanks to an awakening of interest in both contemporary topics and political history (although there is no consensus when it comes to defining political history). The aim of this article is to summarise these recent developments in Portuguese historiography for the benefit of an English-language audience. Keywords Nineteenth Century, History, Bibliography, Constitutionalism, Historiography, Liberalism, Political History, Portugal Politics has finally begun to carve out a privileged space at the heart of Portuguese historiography. This ‘invasion’ is a recent phenomenon and can be explained by the gradual acceptance, over the course of two decades, of political history as a genuine specialisation in Portuguese academic circles. This process of scientific and pedagogical renewal has seen a clear focus also on the nineteenth century. Young researchers concentrate their efforts in this field, and publishers are more interested in this kind of works than before. In Portugal, the interest in the 19th century is a reaction against decades of ignorance. Until April 1974, ideological reasons dictated the absence of contemporary history from the secondary school classroom, and even from the university curriculum. -

Television Coverage of British Party Conferences in the 1990S: the Symbiotic Production of Political News

Television Coverage of British Party Conferences in the 1990s: The Symbiotic Production of Political News James Benedict Price Stanyer PhD thesis submitted in the Department of Government London School of Economics and Political Science 1 UMI Number: U120754 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U120754 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 Abstract Studies of political communication in the UK have focused primarily on election campaigns and reportage of parliamentary and public policy issues. In these contexts, two or more parties compete for coverage in the news media. However, the main British party conferences present a different context, where one party’s activities form the (almost exclusive) focus of the news media's attention for a week, and that party’s leadership ‘negotiates* coverage in a direct one-to-one relationship. Conference weeks are the key points in the organizational year for each party (irrespective of their internal arrangements), and a critical period for communicating information about the party to voters at large, especially via television news coverage, which forms the focus of this study. -

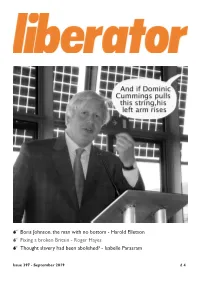

Harold Elletson 0 Fixing a Broken Britain

0 Boris Johnson, the man with no bottom - Harold Elletson 0 Fixing a broken Britain - Roger Hayes 0 Thought slavery had been abolished? - Isabelle Parasram Issue 397 - September 2019 £ 4 Issue 397 September 2019 SUBSCRIBE! CONTENTS Liberator magazine is published six/seven times per year. Subscribe for only £25 (£30 overseas) per year. Commentary .................................................................................3 You can subscribe or renew online using PayPal at Radical Bulletin .............................................................................4..5 our website: www.liberator.org.uk THE MAN WITH NO BOTTOM ................................................6..7 Or send a cheque (UK banks only), payable to Boris Johnson might see himself as a ’great man’, but is an empty vessel “Liberator Publications”, together with your name without values says former Tory MP Harold Elletson and full postal address, to: IT’S TIME FOR US TO FIX A BROKEN BRITAIN ....................8..9 After three wasted years and the possible horror of Brexit it’s time Liberator Publications for the Liberal Democrat to take the lead in creating a reformed Britain, Flat 1, 24 Alexandra Grove says Roger Hayes London N4 2LF England ANOTHER ALLIANCE? .............................................................10..11 Should there be a Remain Alliance involving Liberal Democrats at any imminent general election? Liberator canvassed some views, THE LIBERATOR this is what we got COLLECTIVE Jonathan Calder, Richard Clein, Howard Cohen, IS IT OUR FAULT? .....................................................................12..13 -

SECURITY with FREEDOM the Challenge for Liberals

SECURITY WITH FREEDOM The Challenge for Liberals The current obsession of the Western World is the search for security – whether it is security from international terrorism, from muggers on our streets, from kids hanging around outside the local shop and of course from the marauding hordes of paedophiles. We feel that we have lost control of our lives in a world dominated by the mysterious and unaccountable forces of globalisation and the seemingly ever more rapid and incomprehensible pace of technological change – all of it reported to us coated in political spin and trivialised and sensationalised by media frenzy. In a world seemingly gone mad we yearn for old values of community and unchanging certainties. We long for that rose covered cottage where we know and like everyone in the village and our door remains safely unlocked at all times. To achieve that we are happy – at each and every level – to “give up a little freedom” in order to gain some sort of assurance of “security”. Indeed there are those who would seek security at any price. Of course this all started long before 11th September 2001 but the events of that day have now become the ultimate excuse on a grand scale for the search for security at whatever cost to freedom. Of course people are entitled to yearn for security but – argues Mike Oborski – in giving up freedom we are not achieving security we are instead merely giving up freedom while failing to achieve security. To achieve security we need greater freedom because it is only with greater and truly informed freedom that we can change society and the world to preserve and extend both freedom and security. -

Launch of New Liberal Birmingham Group!

Internationalism has always been central to Liberalism: speaking to the 2017 Liberal Party Assembly, Cllr Steve Radford urged Liberals to change the Commonwealth of Democracies policy to the more pragmatic approach of broadening the membership and entry criteria for the Commonwealth of Nations (formerly the British Commonwealth). The concept of a Commonwealth of Democracies implied another layer of international organisation, without any lead country calling for it. Ever since the Kampala Conference the Commonwealth has already been open to exceptional cases of countries joining without the strong, historic link of having been formerly part of the British Empire. Previous examples were Mozambique, Rwanada, and the case of predominately French Speaking Cameron (even though the country had a former British territory in the north). The Commonwealth has a proven track record of supporting growing democracies and taking action against countries which failed to support these ideals, such as Apartheid South Africa and Fiji. By removing the exceptional basis, Commonwealth membership could and would expand and the well-respected benefits of Commonwealth co-operation would be extended to other democracies and most importantly those countries seeking to strengthen their democratic institutions. This policy would progress the same objectives as the Commonwealth of Democracies policy but could be immediately implemented and uses an established network internationally known and respected. We need Liberal policies such as this to be tailored both to illustrate our idealistic vision and to be presented to the public as realistic to implement. The text of the two motions as supported by the Bristol Assembly are produced in full on the next page. -

85 Reynolds Strange Survival Liberal Lancashire

THE StrANGE SURVIVAL OF LIBERAL LANCAShirE The story of the decline of the Liberal Party after 1918 is well known. With the rise of class politics the Liberals were squeezed between the advance of Labour and the exodus of the middle classes to the Tories. Liberalism disintegrated in industrial and urban Britain and was pushed back to rural enclaves in the ‘Celtic fringe’, where it held on precariously until the 1960s when, reinvented by Jo Grimond as a radical alternative to Labour, the party spread back into the suburbs. he survival of the Liberals The persistence of this Pennine Jaime Reynolds as a significant local force outpost of Liberalism is conven- examines one exception Tin the Lancashire and York- tionally attributed to the strength shire textile districts throughout of Nonconformity and the Liber- to this story: the this period is a striking exception als’ collusion with the Conserva- to this general picture. The party’s tives in anti-Labour pacts. Thus resilience of the Liberal decline here was slower than in Peter Clarke has lamented that Party in the Lancashire other parts of urban Britain with after 1914 the Liberals could win the result that by the mid-1950s elections there only on the basis of cotton districts between over two-thirds of the Liberals’ ‘a sort of Nonconformist bastard remaining local government repre- Toryism’. 2 This does not do jus- the 1920s and the 1970s. sentation came from the region.1 tice to the continuing vigour of 20 Journal of Liberal History 85 Winter 2014–15 THE StrANGE SURVIVAL OF LIBERAL LANCAShirE Pennine Radicalism which, at least availability of digital sources4 on and thereafter the Liberals secured until 1945 and in some places later, local history to map the main con- only isolated victories. -

Fairness and Unfairness in South Australian Elections

Fairness and Unfairness in South Australian Elections Glynn Evans Thesis submitted for the degree of Master of Arts Politics Department University of Adelaide July 2005 Table Of Contents Chapter I Fairness and Unfairness in South Australian Elections 1 Theoretical Framework of Thesis 4 Single-Member Constituencies and Preferential Voting 7 Chapter 2 The Importance of Electoral System 11 Electoral Systems and Parly Systems t7 Duverger's 'Law' Confirmed in South Australia l9 Chapter 3 South Australia Under Weighted Voting 22 Block Vote Methods Pre-1936 23 Preferential Voting 1938-197 5 32 The 1969 Changes 38 Comparative Study: Federal Elections 1949-197 7 42 Chapter 4 South Australia Under One Vote One Value 51 South Aushalian Elections 197 7 -1982 52 The 1985 and 1989 Elections 58 What the 1991 Report Said 60 Comparative Study: the 1989 Westem Australian Election 67 Comparative Study: the 1990 Federal Election 7l Chapter 5 The X'airness Clause Develops 75 Parliamentary Debates on the Faimess Clause 75 The 199 1 Redistribution Report 80 Changes to Country Seats 81 Changes to Mehopolitan Seats 83 What Happened at the 1993 Election 86 The 1994 Redistribution and the Sitting Member Factor 88 The 1997 Election 95 Chapter 6 The Fairness Clause Put to the Test 103 The 1998 Redistribution 103 The2002 Election 106 Peter Lewis and the Court of Disputed Returns Cases 110 Chapter 7 Other Ways of Achieving Fairness Itg Hare-Clark t23 Mixed Systems: MMP and Parallel 13s New Zealand under MMP 136 Parallel Systems t45 Optional Preferential Voting t47 -

Doux Commerce, Religion, and the Limits of Antidiscrimination Law Nathan B

College of William & Mary Law School William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository Faculty Publications Faculty and Deans 2017 Doux Commerce, Religion, and the Limits of Antidiscrimination Law Nathan B. Oman William & Mary Law School, [email protected] Repository Citation Oman, Nathan B., "Doux Commerce, Religion, and the Limits of Antidiscrimination Law" (2017). Faculty Publications. 1842. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/facpubs/1842 Copyright c 2017 by the authors. This article is brought to you by the William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/facpubs Doux Commerce, Religion, and the Limits of Antidiscrimination Law* NATHAN B. OMANt INTRODUCTION ......................................................... 693 I. RELIGION, SAME-SEX MARRIAGE, AND THE SCOPE OF ANTIDISCRIMINATION LAW...................................... 697 II. THE PUBLIC THEORY OF THE MARKET AND THE PRIVATE THEORY OF THE MARKET .......................................................... 703 A. THE PUBLIC THEORY OF THE MARKET........... .................. 703 B. THE PRIVATE THEORY OF THE MARKET ......................... 706 III. Doux COMMERCE AND THE REACH OF ANTIDISCRIMINATION LAWS.............. 709 A. THE Doux COMMERCE THEORY OF THE MARKET ........ ............ 710 B. Doux COMMERCE AND THE SCOPE OF ANTIDISCRIMINATION LAW ........ 714 C. OBJECTIONS AND RESPONSES......................... ............ 725 CONCLUSION ................................................... ......... 732 INTRODUCTION We are used to thinking about law and religion -

63 Egan Radical Action

Radical ActioN AND thE LIBEral PartY DUriNG thE SEcoND World War Radical Action was Unlike Common uring the Sec- ond World War, an influential pressure Wealth, Radical the main politi- group within the Action did not break cal parties agreed Liberal Party during free from the existing to suspend the Dnormal contest for seats in Par- the Second World party structure, but liament and on local councils. Well observed at first, the truce War. It questioned remained within increasingly came under chal- the necessity for the the Liberal Party. It lenge from independents of vari- ous hues and the newly created wartime electoral played a major role Common Wealth Party. Radical truce, campaigned in preserving the Action – originally known as the Liberal Action Group – was enthusiastically independence of the formed by Liberals who wished in support of the party after 1945 and to break the truce. Supported by a number of party activists, Beveridge Report, in arguing for social including a number of sitting and urged the MPs and ‘rising stars’, Radical liberalism at a time Action also campaigned success- party leadership to when economic fully to keep the Liberals out of a post-war coalition. The group fight the post-war liberals were in the had a significant influence on general election as an ascendant. Mark Egan the Liberal Party’s attitude to the 1 Conservative Party and helped independent entity. tells its story. ensure the party’s survival as an 4 Journal of Liberal History 63 Summer 2009 Radical ActioN AND thE LIBEral PartY DUriNG thE SEcoND World War independent entity in the post- July 1941, following the failure Johnson was a rebel who war era. -

Download Site Where Ppcs Can Obtain Campaigning Material and Advice

A University of Sussex DPhil thesis Available online via Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/ This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Please visit Sussex Research Online for more information and further details 1 Obeying the iron law? Changes to the intra-party balance of power in the British Liberal Democrats since 1988. Emma Sanderson-Nash UNIVERSITY OF SUSSEX Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy July 2011 2 I hereby declare that this thesis has not been and will not be, submitted in whole or in part to another University for the award of any other degree. Signature:……………………………………… Date……………………………………… The information contained within this thesis are derived from a series of semi-structured interviews conducted with 70 individuals, listed fully in Appendix A between January 2008 and July 2011. The thesis has not been worked on jointly or collaboratively. The conclusions arrived at formed part of a contribution to the following publications: Bale T & Sanderson-Nash E (2011). A Leap of Faith and a Leap in the Dark: The Impact of Coalition on the Conservatives and Liberal Democrats. The Cameron-Clegg Government: Coalition Politics in an Age of Austerity. -

Norman Book Draft V4

Published in 2015 by Lamb for Leader, 95 New Cavendish Street, London, W1W 6XF © Norman Lamb 1 Contents 1/The watchtowers 4 2/Coming to terms with a tragedy 7 We lost because we lost trust. 10 We lost because we didn’t reach out beyond the party. 12 We lost because we identified too closely with Whitehall. 14 3/Giving power to people 17 Giving power to people 19 Giving rights of self-determination. 21 Trusting people. 22 4/A plan of action, a promise of more 24 We need to get ahead in election techniques 26 We need to open up party structures. 27 We need to be an intellectual powerhouse 29 Opportunity 1. Young people are Liberals too 34 Opportunity 2. We need an answer to entrenched poverty 37 Opportunity 3. We need a new approach to prosperity 50 5/My journey 58 2 “The Liberal Democrat leadership contender Norman Lamb has made the perfect case for the continued existence of his party...” Editorial in the Independent, June 2015 3 1/The watchtowers My dad was a climate scientist, a Quaker and a pacifist. He believed in seeking out the evidence for the research he was doing, and as au- thentically as possible. That meant, while other families might have gone to Torremolinos or Brittany, we would go to the Faroe Islands and Finland – north of the Arctic Circle – in pursuit of weather records. I remember in particular one trip to West Germany. One day we drove out into the countryside, and the country lane we were on just came to an end.