History of Mankind: Cultural and Scientific Developments, 6 Vols

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Oversight of the Smithsonian Institution

OVERSIGHT OF THE SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION HEARING BEFORE THE COMMITTEE ON HOUSE ADMINISTRATION HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED SIXTEENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION SEPTEMBER 18, 2019 Printed for the use of the Committee on House Administration ( Available on the Internet: https://govinfo.gov/committee/house-administration U.S. GOVERNMENT PUBLISHING OFFICE 38–520 WASHINGTON : 2019 VerDate Sep 11 2014 21:08 Dec 30, 2019 Jkt 038520 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 E:\HR\OC\A520.XXX A520 lotter on DSKBCFDHB2PROD with HEARING VerDate Sep 11 2014 21:08 Dec 30, 2019 Jkt 038520 PO 00000 Frm 00002 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 E:\HR\OC\A520.XXX A520 lotter on DSKBCFDHB2PROD with HEARING C O N T E N T S SEPTEMBER 18, 2019 Page Oversight of the Smithsonian Institution .............................................................. 1 OPENING STATEMENTS Chairperson Zoe Lofgren ......................................................................................... 1 Prepared statement of Chairperson Lofgren .................................................. 3 Hon. Rodney Davis, Ranking Member ................................................................... 5 Prepared statement of Ranking Member Davis ............................................. 7 WITNESSES Mr. Lonnie G. Bunch, III, Secretary, Smithsonian Institution ............................ 10 Prepared statement of Secretary Bunch ......................................................... 13 Ms. Cathy L. Helm, Inspector General, Smithsonian Institution ....................... 17 Prepared statement -

Library of Congress Magazine January/February 2018

INSIDE PLUS A Journey Be Mine, Valentine To Freedom Happy 200th, Mr. Douglass Find Your Roots Voices of Slavery At the Library LIBRARY OF CONGRESS MAGAZINE JANUARY/FEBRUARY 2018 Building Black History A New View of Tubman LOC.GOV LIBRARY OF CONGRESS MAGAZINE Library of Congress Magazine Vol. 7 No. 1: January/February 2018 Mission of the Library of Congress The Library’s central mission is to provide Congress, the federal government and the American people with a rich, diverse and enduring source of knowledge that can be relied upon to inform, inspire and engage them, and support their intellectual and creative endeavors. Library of Congress Magazine is issued bimonthly by the Office of Communications of the Library of Congress and distributed free of charge to publicly supported libraries and research institutions, donors, academic libraries, learned societies and allied organizations in the United States. Research institutions and educational organizations in other countries may arrange to receive Library of Congress Magazine on an exchange basis by applying in writing to the Library’s Director for Acquisitions and Bibliographic Access, 101 Independence Ave. S.E., Washington DC 20540-4100. LCM is also available on the web at loc.gov/lcm/. All other correspondence should be addressed to the Office of Communications, Library of Congress, 101 Independence Ave. S.E., Washington DC 20540-1610. [email protected] loc.gov/lcm ISSN 2169-0855 (print) ISSN 2169-0863 (online) Carla D. Hayden Librarian of Congress Gayle Osterberg Executive Editor Mark Hartsell Editor John H. Sayers Managing Editor Ashley Jones Designer Shawn Miller Photo Editor Contributors Bryonna Head Wendi A. -

The National Museum of African American History and Culture

The National Museum of African American History and Culture: A Museum 100 Years in the Making Sarah J. Beer History 489: Research Seminar December 9, 2016 Contents Abstract…………………………………………………………………………………………………...iii Introduction………………………………………………………………………………………………..1 Congressional History of the NMAAHC: 1916-1930……………………………………………………2 Early Reviews of NMAAHC……………………………………………………………………………...6 Contents of the Museum…………………………………………………………………………………10 History Gallery: Slavery and Freedom, 1400-1877………………………………………………12 History Gallery: Defending freedom, Defining Freedom: The Era of Segregation, 1876-1968…15 History Gallery: A Changing America: 1968 and Beyond……………………………………….18 Culture Galleries, Community Galleries, and More……………………………………………...21 Personal Review and Critique of NMAAHC…………………………………………………………...22 Conclusion………………………………………………………………………………………………...25 Works Cited………………………………………………………………………………………………27 Works Consulted…………………………………………………………………………………………28 ii Abstract: The Smithsonian Institution has been making headlines in recent news for one momentous reason: the opening of a new museum commemorating African American history. Beginning in 1916, several bills, resolutions, and hearings have taken place in Congress to introduce legislation that would create a museum, but none would be successful. John Lewis picked up the fight by introducing legislation immediately after becoming a Georgia congressman in 1986. It took Lewis almost twenty years, but in 2003 President George W. Bush finally signed the law to create the National Museum of African American History and Culture. My capstone paper studies the congressional history, early reviews, and content of the museum while also including my personal review: as a public history student, I pay close attention to how the museum presents the content and narrative, as well as the content and narrative themselves. I am able to do this because a research grant through the Office of Research and Sponsored Programs gave me the opportunity to visit the museum in early November. -

Programs & Exhibitions

PROGRAMS & EXHIBITIONS Winter/Spring 2020 To purchase tickets by phone call (212) 485-9268 letter | exhibitions | calendar | programs | family | membership | general information Dear Friends, Until recently, American democracy wasn’t up for debate—it was simply fundamental to our way of life. But things have changed, don’t you agree? According to a recent survey, less than a third of Americans born after 1980 consider it essential to live in a democracy. Here at New-York Historical, our outlook is nonpartisan Buck Ennis, Crain’s New York Business and our audiences represent the entire political spectrum. But there is one thing we all agree on: living in a democracy is essential indeed. The exhibitions and public programs you find in the following pages bear witness to this view, speaking to the importance of our democratic principles and the American institutions that carry them out. A spectacular new exhibition on the history of women’s suffrage in our Joyce B. Cowin Women’s History Gallery this spring sheds new light on the movements that led to the ratification of the 19th Amendment to the Constitution 100 years ago; a major exhibition on Bill Graham, a refugee from Nazi Germany who brought us the Grateful Dead, Jefferson Airplane, Jimi Hendrix, and many other staples of rock & roll, stresses our proud democratic tradition of welcoming immigrants and refugees; and, as part of a unique New-York Historical–Asia Society collaboration during Asia Society’s inaugural Triennial, an exhibition of extraordinary works from both institutions will be accompanied by a new site-specific performance by drummer/composer Susie Ibarra in our Patricia D. -

Blacklist100 E-Book 14JUL2020 V2.3

Table of Contents 04: Curatorial Note 10: Open Letter on Race 19: Short Essay: Celebrating Blackness on Juneteenth 25: Artist Statement & Works (Elizabeth Colomba) 28: Short Essay: Who sets the standards for equality (E’lana Jordan) 31: Category 1: Cause & Community 58: Category 2: Industry & Services 85: Spoken Word Poem: A-head of the School 86: Category 3: Marketing, Communication & Design 113: Spoken Word Poem: Culture Storm 114: Category 4: Media, Arts & Entertainment 141: Category 5: STEM & Healthcare 168: Full 2020 blacklist100 171: Closing Acknowledgements 2 Curatorial Note This e-book originated as a post on LinkedIn the week following the death of George Floyd. The post included an 8-page document entitled an “Open Letter on Race." The letter was released as a 25-minute video, also. The central theme of the letter was a reflection on Dr. Martin Luther King’s critical question: “Where do we go from here?" Leading into the week of Juneteenth, the Open Letter on Race received over 30,000 views, shares, and engagements. Friends were inspired to draft essays sharing their stories; and this book represents their collective energy. In the arc of history, we stand hopeful that we have now reached a long-awaited inflection point; this book is a demonstration that the People are ready to lead change. This e-book features 100 Black culture-makers & thought-leaders whose message is made for this moment. The theme of this book is “A Call for Change.” This interactive book will never be printed, and has embedded hyperlinks so you can take action now. -

Slavery on Exhibition: Display Practices in Selected Modern American Museums

Slavery on Exhibition: Display Practices in Selected Modern American Museums by Kym Snyder Rice B.A. in Art History, May 1974, Sophie Newcomb College of Tulane University M.A. in American Studies, May 1979, University of Hawaii-Manoa A Dissertation submitted to The Faculty of The Columbian College of Arts and Sciences of The George Washington University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy January 31, 2015 Dissertation directed by Teresa Anne Murphy Associate Professor of American Studies The Columbian College of Arts and Sciences of The George Washington University Certifies that Kym Snyder Rice has passed the Final Examination for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy as of November 22, 2014. This is the final approved form of the dissertation. Slavery on Exhibition: Display Practices in Selected Modern American Museums Kym Snyder Rice Dissertation Research Committee: Teresa Anne Murphy, Associate Professor of American Studies, Dissertation Director Barney Mergen, Professor Emeritus of American Studies, Committee Member Nancy Davis, Professorial Lecturer of American Studies, Committee Member ii © Copyright 2015 by Kym Snyder Rice All rights reserved iii Acknowledgements This dissertation has taken many years to complete and I have accrued many debts. I remain very grateful for the ongoing support of all my friends, family, Museum Studies Program staff, faculty, and students. Thanks to each of you for your encouragement and time, especially during the last year. Many people contributed directly to my work with their suggestions, materials, and documents. Special thanks to Fath Davis Ruffins and Elizabeth Chew for their generosity, although they undoubtedly will not agree with all my conclusions. -

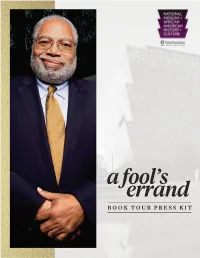

A Fool's Errand Social Media Toolkit

BOOK TOUR PRESS KIT SELECTED QUOTES Preface “I saw the journey to build a museum that could help bridge the chasms that divide us as a ‘fool’s errand,’ but an errand worthy of the burdens … a journey that could help, using history and culture as a tool, a nation come to grips with its tortured racial past and maybe find understanding and hope through creation of a museum.” (Page x) Chapter 1 “I craved to be part of an institution that was of value both in the traditional ways of curating exhibitions, enriching education opportunities, and preserving collections and in nontraditional ways, such as being a safe space where issues of social justice, fairness, and racial reconciliation are central to the soul of the museum … I wanted a museum that was not intimidating but as comfortable as the backyard barbecues of my childhood.” (Page 10) Chapter 2 “One can tell a great deal about a country by what it remembers. By what graces the walls of its museums. And what monuments have privileged placement in parks … Yet one learns even more about a nation by what it forgets. What moments of evil, disappointment, and defeat are downplayed or eliminated from the national narratives.” (Page 25) “NMAAHC would not be a museum by black people for black people, not an ancillary narrative, but the quintessential American story. If one wants to understand core American values of optimism, resiliency, and spirituality, where better to look than African American history?” (Page 28) Chapter 3 “In the summer of 2018 I spoke at the Edinburgh International Culture Summit. -

Press Release

Contact: Communications Department 212-857-0045 [email protected] media release Let Your Motto Be Resistance: African American Portraits On view from James U. Stead (active c. 1881) Henry Highland Garnet, c. 1881 May 11 through National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution September 9, 2007 Media Preview May 10, 2007 9:30 - 11am RSVP: [email protected] 212.857.0045 David Moses Attie, Lorraine Hansberry, c. 1960. National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution Louise Dahl-Wolfe, William Edmondson, 1933. ©1989, Center for Creative Photography, Arizona Board of Regents, National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution Teacher, preacher, editor, and abolitionist, Henry Highland Garnet was an unwavering advocate for racial equality and an electrifying speaker in support of that campaign before and after the Civil War. At the 1843 National Negro Convention in Albany, N.Y., Garnet unleashed a rallying cry, urging “the slaves of the United States of America” to rise up and emancipate themselves: “Let your Motto be resistance! Resistance! RESISTANCE! No oppressed people have ever secured Liberty without resistance.” American history is retold through the photographic portraits of celebrated African Americans in Let Your Motto Be Resistance: African American Portraits, the inaugural exhibition of the new National Museum of African American History and Culture (NMAAHC) in Washington D.C. The exhibition will be on view at the International Center of Photography (1133 Avenue of the Americas at 43rd Street), from May 11 through September 9, 2007. This collection of photographs traces 150 years of American history through the lives of well-known abolitionists, artists, scientists, writers, statesmen, entertainers, and sports figures. NMAAHC is the Smithsonian’s nineteenth and newest museum, with plans for building a major complex on Washington’s National Mall in under a decade. -

Lonnie G. Bunch III and Richard D. Parsons

Americans for the Arts presents The 31st Annual Nancy Hanks Lecture on Arts and Public Policy A conversation with Lonnie G. Bunch III and Richard D. Parsons March 12, 2018 Eisenhower Theater The John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts Washington, D.C. C 0 C 0 M 53 M 2 Sponsored By: Rosenthal Family Foundation Y 100 Y 0 Ovation PANTONE PANTONE The Max and Victoria Dreyfus Foundation,7413 Inc. K 4 Cool Gray 11 K 68 March 2018 The Americans for the Arts 31st Annual Nancy Hanks Lecture on Arts and Public Policy 1 friend, John Peede, the newly nominated Chairman of the OPENING REMARKS BY National Endowment for the Humanities. And to Jane and to ROBERT L. LYNCH John I want to say that this is an audience that believes in the power of the arts and humanities to transform people’s lives and their communities. They believe in what you do. Along with the 1,200 people who are here tonight, there are millions more who stand committed to ensuring that the federal government remains invested in the future of that vision. And along with the 1,200 people who are here tonight, there are millions more who stand committed to ensuring that the federal government remains invested in the future of that vision through the National Endowment for the Arts, the National Endowment for the Humanities, the Institute of Museum and Library Services, the Corporation for Public Broadcasting and the Arts Education Support of the Department of Education. As you all know, last year at this time, we faced a major threat to the federal cultural agencies. -

Award Honorary Degrees Funding

6 Board Meeting March 12, 2020 AWARD HONORARY DEGREES, URBANA Action: Award Honorary Degrees Funding: No New Funding Required The University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Senate has nominated the following persons for conferral of honorary degrees at the Commencement exercises in May 2020. The Chancellor, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, and Vice President, University of Illinois recommends approval of these nominations. Lonnie Bunch III, Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution -- the honorary degree of Doctor of Humane Letters Lonnie Bunch III made history when he was the first African American named Secretary of the Smithsonian Institutions. In that capacity, he oversees the most prestigious and arguably most comprehensive museum complexes in the world. His portfolio includes 19 museums, 21 libraries, the National Zoo, numerous research centers, and several education units and centers. The Smithsonian, as this complex is commonly referred to, hosts upward of 30 million visitors a year and has an annual budget of $1.2 million. Previously, Bunch was the director of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture. When he started as director in July 2005, he had one staff member, no collections, no funding, and no site for a museum. Driven by optimism, determination and commitment to build “a place that would make America better,” Bunch transformed a vision into a bold reality. The museum has welcomed more than 6 million visitors since it opened in September 2016 and compiled a collection of 40,000 objects that are housed in the first “green building” on the National Mall. 2 In his capacity as historian and educator, Bunch has been in the museum business for practically his entire career, including years of service in Illinois. -

Black Popular Culture

BLACK POPULAR CULTURE THE POPULAR CULTURE STUDIES JOURNAL AFRICOLOGY: A:JPAS THE JOURNAL OF PAN AFRICAN STUDIES Volume 8 | Number 2 | September 2020 Special Issue Editor: Dr. Angela Spence Nelson Cover Art: “Wakanda Forever” Dr. Michelle Ferrier POPULAR CULTURE STUDIES JOURNAL VOLUME 8 NUMBER 2 2020 Editor Lead Copy Editor CARRIELYNN D. REINHARD AMY DREES Dominican University Northwest State Community College Managing Editor Associate Copy Editor JULIA LARGENT AMANDA KONKLE McPherson College Georgia Southern University Associate Editor Associate Copy Editor GARRET L. CASTLEBERRY PETER CULLEN BRYAN Mid-America Christian University The Pennsylvania State University Associate Editor Reviews Editor MALYNNDA JOHNSON CHRISTOPHER J. OLSON Indiana State University University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Associate Editor Assistant Reviews Editor KATHLEEN TURNER LEDGERWOOD SARAH PAWLAK STANLEY Lincoln University Marquette University Associate Editor Graphics Editor RUTH ANN JONES ETHAN CHITTY Michigan State University Purdue University Please visit the PCSJ at: mpcaaca.org/the-popular-culture-studies-journal. Popular Culture Studies Journal is the official journal of the Midwest Popular Culture Association and American Culture Association (MPCA/ACA), ISSN 2691-8617. Copyright © 2020 MPCA. All rights reserved. MPCA/ACA, 421 W. Huron St Unit 1304, Chicago, IL 60654 EDITORIAL BOARD CORTNEY BARKO KATIE WILSON PAUL BOOTH West Virginia University University of Louisville DePaul University AMANDA PICHE CARYN NEUMANN ALLISON R. LEVIN Ryerson University Miami University Webster University ZACHARY MATUSHESKI BRADY SIMENSON CARLOS MORRISON Ohio State University Northern Illinois University Alabama State University KATHLEEN KOLLMAN RAYMOND SCHUCK ROBIN HERSHKOWITZ Bowling Green State Bowling Green State Bowling Green State University University University JUDITH FATHALLAH KATIE FREDRICKS KIT MEDJESKY Solent University Rutgers University University of Findlay JESSE KAVADLO ANGELA M. -

Is William Martinez Not Our Brother? 3R D R P P

3r d r p p Is William Martinez Not Our Brother? 3r d r p p THE NEW PUBLIC SCHOLARSHIP series editors Lonnie Bunch, Director, National Museum of African-American History and Culture Julie Ellison, Professor of American Culture, University of Michigan Robert Weisbuch, President, Drew University The New Public Scholarship encourages alliances between scholars and commu- nities by publishing writing that emerges from publicly engaged and intellectually consequential cultural work. The series is designed to attract serious readers who are invested in both creating and thinking about public culture and public life. Un- der the rubric of “public scholar,” we embrace campus-based artists, humanists, cul- tural critics, and engaged artists working in the public, nonprofit, or private sector. The editors seek useful work growing out of engaged practices in cultural and educa- tional arenas. We are also interested in books that offer new paradigms for doing and theorizing public scholarship itself. Indeed, validating public scholarship through an evolving set of concepts and arguments is central to The New Public Scholarship. The universe of potential contributors and readers is growing rapidly. We are teaching a generation of students for whom civic education and community service learning are quite normative. The civic turn in art and design has affected educational and cultural institutions of many kinds. In light of these developments, we feel that The New Public Scholarship offers a timely innovation in serious pub- lishing. DIGITALCULTUREBOOKS is an imprint of the University of Michigan Press and the Scholarly Publishing Office of the University of Michigan Library dedicated to publishing innovative and accessible work explor- ing new media and their impact on society, culture, and scholarly communication.