Verdi, 'Tutte Le Feste'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MICHAEL FINNISSY at 70 the PIANO MUSIC (9) IAN PACE – Piano Recital at Deptford Town Hall, Goldsmith’S College, London

City Research Online City, University of London Institutional Repository Citation: Pace, I. (2016). Michael Finnissy at 70: The piano music (9). This is the other version of the paper. This version of the publication may differ from the final published version. Permanent repository link: https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/17520/ Link to published version: Copyright: City Research Online aims to make research outputs of City, University of London available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the author(s) and/or copyright holders. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to. Reuse: Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. City Research Online: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/ [email protected] MICHAEL FINNISSY AT 70 THE PIANO MUSIC (9) IAN PACE – Piano Recital at Deptford Town Hall, Goldsmith’s College, London Thursday December 1st, 2016, 6:00 pm The event will begin with a discussion between Michael Finnissy and Ian Pace on the Verdi Transcriptions. MICHAEL FINNISSY Verdi Transcriptions Books 1-4 (1972-2005) 6:15 pm Books 1 and 2: Book 1 I. Aria: ‘Sciagurata! a questo lido ricercai l’amante infido!’, Oberto (Act 2) II. Trio: ‘Bella speranza in vero’, Un giorno di regno (Act 1) III. Chorus: ‘Il maledetto non ha fratelli’, Nabucco (Part 2) IV. -

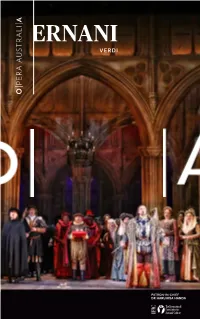

Ernani Program

VERDI PATRON-IN-CHIEF DR HARUHISA HANDA Celebrating the return of World Class Opera HSBC, as proud partner of Opera Australia, supports the many returns of 2021. Together we thrive Issued by HSBC Bank Australia Limited ABN 48 006 434 162 AFSL No. 232595. Ernani Composer Ernani State Theatre, Giuseppe Verdi (1813-1901) Diego Torre Arts Centre Melbourne Librettist Don Carlo, King of Spain Performance dates Francesco Maria Piave Vladimir Stoyanov 13, 15, 18, 22 May 2021 (1810-1876) Don Ruy Gomez de Silva Alexander Vinogradov Running time: approximately 2 hours and 30 Conductor Elvira minutes, including one interval. Carlo Montanaro Natalie Aroyan Director Giovanna Co-production by Teatro alla Scala Sven-Eric Bechtolf Jennifer Black and Opera Australia Rehearsal Director Don Riccardo Liesel Badorrek Simon Kim Scenic Designer Jago Thank you to our Donors Julian Crouch Luke Gabbedy Natalie Aroyan is supported by Costume Designer Roy and Gay Woodward Kevin Pollard Opera Australia Chorus Lighting Designer Chorus Master Diego Torre is supported by Marco Filibeck Paul Fitzsimon Christine Yip and Paul Brady Video Designer Assistant Chorus Master Paul Fitzsimon is supported by Filippo Marta Michael Curtain Ina Bornkessel-Schlesewsky and Matthias Schlesewsky Opera Australia Actors The costumes for the role of Ernani in this production have been Orchestra Victoria supported by the Concertmaster Mostyn Family Foundation Sulki Yu You are welcome to take photos of yourself in the theatre at interval, but you may not photograph, film or record the performance. -

La Traviata Synopsis 5 Guiding Questions 7

1 Table of Contents An Introduction to Pathways for Understanding Study Materials 3 Production Information/Meet the Characters 4 The Story of La Traviata Synopsis 5 Guiding Questions 7 The History of Verdi’s La Traviata 9 Guided Listening Prelude 12 Brindisi: Libiamo, ne’ lieti calici 14 “È strano! è strano!... Ah! fors’ è lui...” and “Follie!... Sempre libera” 16 “Lunge da lei...” and “De’ miei bollenti spiriti” 18 Pura siccome un angelo 20 Alfredo! Voi!...Or tutti a me...Ogni suo aver 22 Teneste la promessa...” E tardi... Addio del passato... 24 La Traviata Resources About the Composer 26 Online Resources 29 Additional Resources Reflections after the Opera 30 The Emergence of Opera 31 A Guide to Voice Parts and Families of the Orchestra 35 Glossary 36 References Works Consulted 40 2 An Introduction to Pathways for Understanding Study Materials The goal of Pathways for Understanding materials is to provide multiple “pathways” for learning about a specific opera as well as the operatic art form, and to allow teachers to create lessons that work best for their particular teaching style, subject area, and class of students. Meet the Characters / The Story/ Resources Fostering familiarity with specific operas as well as the operatic art form, these sections describe characters and story, and provide historical context. Guiding questions are included to suggest connections to other subject areas, encourage higher-order thinking, and promote a broader understanding of the opera and its potential significance to other areas of learning. Guided Listening The Guided Listening section highlights key musical moments from the opera and provides areas of focus for listening to each musical excerpt. -

Il Trovatore Was Made Stage Director Possible by a Generous Gift from Paula Williams the Annenberg Foundation

ilGIUSEPPE VERDItrovatore conductor Opera in four parts Marco Armiliato Libretto by Salvadore Cammarano and production Sir David McVicar Leone Emanuele Bardare, based on the play El Trovador by Antonio García Gutierrez set designer Charles Edwards Tuesday, September 29, 2015 costume designer 7:30–10:15 PM Brigitte Reiffenstuel lighting designed by Jennifer Tipton choreographer Leah Hausman The production of Il Trovatore was made stage director possible by a generous gift from Paula Williams The Annenberg Foundation The revival of this production is made possible by a gift of the Estate of Francine Berry general manager Peter Gelb music director James Levine A co-production of the Metropolitan Opera, Lyric Opera of Chicago, and the San Francisco principal conductor Fabio Luisi Opera Association 2015–16 SEASON The 639th Metropolitan Opera performance of GIUSEPPE VERDI’S il trovatore conductor Marco Armiliato in order of vocal appearance ferr ando Štefan Kocán ines Maria Zifchak leonor a Anna Netrebko count di luna Dmitri Hvorostovsky manrico Yonghoon Lee a zucena Dolora Zajick a gypsy This performance Edward Albert is being broadcast live on Metropolitan a messenger Opera Radio on David Lowe SiriusXM channel 74 and streamed at ruiz metopera.org. Raúl Melo Tuesday, September 29, 2015, 7:30–10:15PM KEN HOWARD/METROPOLITAN OPERA A scene from Chorus Master Donald Palumbo Verdi’s Il Trovatore Musical Preparation Yelena Kurdina, J. David Jackson, Liora Maurer, Jonathan C. Kelly, and Bryan Wagorn Assistant Stage Director Daniel Rigazzi Italian Coach Loretta Di Franco Prompter Yelena Kurdina Assistant to the Costume Designer Anna Watkins Fight Director Thomas Schall Scenery, properties, and electrical props constructed and painted by Cardiff Theatrical Services and Metropolitan Opera Shops Costumes executed by Lyric Opera of Chicago Costume Shop and Metropolitan Opera Costume Department Wigs and Makeup executed by Metropolitan Opera Wig and Makeup Department Ms. -

The Worlds of Rigoletto: Verdiâ•Žs Development of the Title Role in Rigoletto

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2008 The Worlds of Rigoletto Verdi's Development of the Title Role in Rigoletto Mark D. Walters Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC THE WORLDS OF RIGOLETTO VERDI’S DEVELOPMENT OF THE TITLE ROLE IN RIGOLETTO By MARK D. WALTERS A Treatise submitted to the College of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Music Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2008 The members of the Committee approve the Treatise of Mark D. Walters defended on September 25, 2007. Douglas Fisher Professor Directing Treatise Svetla Slaveva-Griffin Outside Committee Member Stanford Olsen Committee Member The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii I would like to dedicate this treatise to my parents, Dennis and Ruth Ann Walters, who have continually supported me throughout my academic and performing careers. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my gratitude to Professor Douglas Fisher, who guided me through the development of this treatise. As I was working on this project, I found that I needed to raise my levels of score analysis and analytical thinking. Without Professor Fisher’s patience and guidance this would have been very difficult. I would like to convey my appreciation to Professor Stanford Olsen, whose intuitive understanding of musical style at the highest levels and ability to communicate that understanding has been a major factor in elevating my own abilities as a teacher and as a performer. -

Table of Contents More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-63535-6 - The Cambridge Companion to Verdi Edited by Scott L. Balthazar Table of Contents More information Contents List of figures and table [page vii] List of examples [viii] Notes oncontributors [x] Preface [xiii] Chronology [xvii] r Part I Personal, cultural, and political context 1Verdi’s life: a thematic biography Mary Jane Phillips-Matz [3] 2The Italian theatre of Verdi’s day Alessandro Roccatagliati [15] 3Verdi, Italian Romanticism, and the Risorgimento Mary Ann Smart [29] r Part II The style of Verdi’s operas and non-operatic works 4Theforms of set pieces Scott L. Balthazar [49] 5Newcurrents in the libretto Fabrizio Della Seta [69] 6Words and music Emanuele Senici [88] 7French influences Andreas Giger [111] 8Structuralcoherence Steven Huebner [139] 9Instrumental music in Verdi’s operas David Kimbell [154] 10 Verdi’s non-operatic works Roberta Montemorra Marvin [169] r Part III Representative operas 11 Ernani: the tenor in crisis Rosa Solinas [185] 12 “Ch’hai di nuovo, buffon?” or What’s new with Rigoletto Cormac Newark [197] 13 Verdi’s Don Carlos:anoverviewoftheoperas Harold Powers [209] 14 Desdemona’s alienation and Otello’s fall Scott L. Balthazar [237] r Part IV Creation and critical reception 15 An introduction to Verdi’s working methods Luke Jensen [257] 16 Verdi criticism Gregory W.Harwood [269] [v] © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-63535-6 - The Cambridge Companion to Verdi Edited by Scott L. Balthazar Table of Contents More information vi Contents Notes [282] List of Verdi’s works [309] Select bibliography and works cited [312] Index [329] © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-63535-6 - The Cambridge Companion to Verdi Edited by Scott L. -

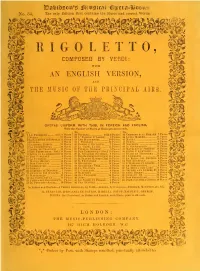

Rigoletto, Composes by Verdi: with an English Version, and the Music of the Principal Airs

No. 34. The only Edition that contains the Music and correct Words. RIGOLETTO, COMPOSES BY VERDI: WITH AN ENGLISH VERSION, AND THE MUSIC OF THE PRINCIPAL AIRS IjIBfipf l^g UNIFORM WITH THIS, IN FOREICN AND ENCLISH, With the Number of Pieces of Music printed in each. No. No. 1 Le Peophete with 9 Pieces 22 Fidklio with 5 Pieces 43 Crispino e la Comare 7 2 Noema 1- Pieces 23 L' Elisiee d'Amore 9 Pieces 44 Luisa Miller 14 3 IlBaebierediSivigliaH Pieces 24 Les Huguenots 10 Pieces 45 Marta 10 4 Otello 8 Pieces 25 I Puritani io Pieces 46 Zampa 8 5 Lucrezia Borgia 15 Pieces 20 Romeo e Giulietta 7 Pines 47 Macbeth 12 La Cekebbntola 10 Pieces 27 La Gazza Ladra 11 Pieces 48 II Giuramento 15 7 Linda di Chamouni ...10 Pieces 2S PiPEi.io (German) 5 Pieces 40 Matrimonio Segreto 10 8 Lek Fbeischtjtz (Hal.) 10 Pieces 2» Der FREiscnuiz (Ger.) lo Pieces 50 Orfeo e Eurydice 8 9 LUCIA DI LamMEEMOOR 10 Pieces so II Seraglio (German)... 7 Pieces > 51 Ballo in Maschera ...12 10 Don Pasquale 6 Pieces 31 Die Zaubeeflote (Ger) 10 Pieces ! 52 I Lombardi 14 11 La Favorita 8 Pieces 32 II Flauto Magico (Ita) 10 Pieces 63 La Forza del Destino 9 12 Medea (Mayer) 10 Pieces 33 II Trovatore 16 Pieces 64 Don Bucefalo 4 18 ]>cm Giovanni 11 Pieces 34, KlGOLETTO 10 Pieces 55 L'Italiana in Algeri... 8 | 50 Precauzioni 8 1 1 Semiramide 10 Pieces 35 Guglielmo Teli. 6 Pieces Le là Kunani 10 Pieces 30 La Traviata 12 Pieces 57 La Donna del Lago ...li Pieces I 8 Pieces 58 Orphee aux Enfees, Fr 9 l'ieres 16 Koiikkto II Diavolo .. -

Download Booklet

2 CDs the ultimate DDD VERDI 8.578068-69 opera album CD 1 innovative style. His effective use of the spectacular, the supernatural, the superstitious, the sentimental, the scandalous, even the downright silly, are evident to everyone familiar with 1 Prelude to La Traviata 3:53 these great operas. But Verdi cannily uses these melodramatic conventions of Romantic opera Slovak Radio Symphony Orchestra, Alexander Rahbari (conductor) to reveal his characters’ psychological situations both directly (through their own words and actions, which of course give rise to their predicaments) and indirectly (as mirrored by, say, the 2 Brindisi: Libiamo ne’ lieti calici from La Traviata 2:54 famous storm in Rigoletto, or by contrasting Aïda’s inner turmoil when she discovers her father Monika Krause (soprano), Yordy Ramiro (tenor), Slovak Philharmonic Chorus, has been taken captive with the Egyptian’s public victory celebrations over the Ethiopians). Slovak Radio Symphony Orchestra, Alexander Rahbari (conductor) Few may find it credible when the old gypsy Azucena reveals that she had mistakenly thrown her own baby into the flames instead of the son of the man who burned her mother at the stake 3 La donna è mobile from Rigoletto 2:55 as a witch, but the disastrous consequences are tragic for all concerned. And the wide-ranging Yordy Ramiro (tenor), Slovak Radio Symphony Orchestra, grand guignol plot of La forza del destino may beggar belief, but it remains a gothic classic, Alexander Rahbari (conductor) complete with its own legendary ‘curse’ which apparently originated when the American baritone Leonard Warren died on the Metropolitan Opera stage on 4 March 1960 while singing Morir, 4 Va, pensiero ‘Chorus of the Hebrew Slaves’ from Nabucco 4:39 tremenda cosa (‘to die, a momentous thing’). -

Page 1 of 18 Musi 6397: Bibliography and Reserves 1/17/2009 File

musi 6397: bibliography and reserves Page 1 of 18 ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY AND RESERVE LIST MUSI 6397, Music and Text in Romantic Italian Opera Professor: Andrew Davis Fall 2008 main page Notes: call numbers indicate items on reserve in the music library. Items are available for two-hour loans; you may want to copy what you need and return the item to the desk. “e reserve” indicates items copies of which are available electronically on Docutek E-reserves, at http://ezproxy.lib.uh.edu/login?url=http://docutek.lib.uh.edu:8081/eres/courseindex.aspx (or, from the main library catalog page, http://library.uh.edu/, follow the “course reserves” and then “electronic reserves" links). no call number and no “e reserve” designation indicates the item is available in a journal the library owns; copy the item and return the journal to the shelf, or check the library catalog (do a "journal title" search) to see if the journal is available in electronic format. Verdi's operas: scores, libretti, and recordings See the University of Chicago Press's summary of the critical edition of the Verdi operas: the first publication in the series (Rigoletto) was in 1983; the most recent (Giovanna d'Arco) is due in April 2009. Factual information that follows is from Roger Parker's article on Verdi in Grove Music Online: http://www.oxfordmusiconline.com.ezproxy.lib.uh.edu/subscriber/article/grove/music/29191pg10. All M3 call numbers are volumes in the Verdi critical edition (The Works of Giuseppe Verdi, University of Chicago Press). All these have at least one supplemental volume associated with the same call number (i.e., M3 .V48 1983 Ser. -

Roger Parker: Curriculum Vitae

1 Roger Parker Publications I Books 1. Giacomo Puccini: La bohème (Cambridge, 1986). With Arthur Groos 2. Studies in Early Verdi (1832-1844) (New York, 1989) 3. Leonora’s Last Act: Essays in Verdian Discourse (Princeton, 1997) 4. “Arpa d’or”: The Verdian Patriotic Chorus (Parma, 1997) 5. Remaking the Song: Operatic Visions and Revisions from Handel to Berio (Berkeley, 2006) 6. New Grove Guide to Verdi and his Operas (Oxford, 2007); revised entries from The New Grove Dictionaries (see VIII/2 and VIII/5 below) 7. Opera’s Last Four Hundred Years (in preparation, to be published by Penguin Books/Norton). With Carolyn Abbate II Books (edited/translated) 1. Gabriele Baldini, The Story of Giuseppe Verdi (Cambridge, 1980); trans. and ed. 2. Reading Opera (Princeton, 1988); ed. with Arthur Groos 3. Analyzing Opera: Verdi and Wagner (Berkeley, 1989); ed. with Carolyn Abbate 4. Pierluigi Petrobelli, Music in the Theater: Essays on Verdi and Other Composers (Princeton, 1994); trans. 5. The Oxford Illustrated History of Opera (Oxford, 1994); translated into German (Stuttgart. 1998), Italian (Milan, 1998), Spanish (Barcelona, 1998), Japanese (Tokyo, 1999); repr. (slightly revised) as The Oxford History of Opera (1996); repr. paperback (2001); ed. 6. Reading Critics Reading: Opera and Ballet Criticism in France from the Revolution to 1848 (Oxford, 2001); ed. with Mary Ann Smart 7. Verdi in Performance (Oxford, 2001); ed. with Alison Latham 8. Pensieri per un maestro: Studi in onore di Pierluigi Petrobelli (Turin, 2002); ed. with Stefano La Via 9. Puccini: Manon Lescaut, special issue of The Opera Quarterly, 24/1-2 (2008); ed. -

Ernani Giuseppe Verdi Operas and Revision

Ernani Giuseppe Verdi Operas and Revision • Oberto, conte di San Bonifacio • First performance: Milan, Scala, 17 Nov 1839. • Un giorno di regio (Il Finto Stanislao) • First performance: Milan, Scala, 5 Sept 1840; alternative title used 1845 • Nabuccodonosor (Nabucco) • first performance: Milan, Scala, 9 March 1842 • Lombardi alla prima crociata • First performed: Milan, Scala, 11 Feb 1843 • Ernani • First performance: Venice, Fenice, 9 March 1844 • I due Foscari • First performance: Rome, Argentina, 3 Nov 1844 • Giovanna d’Arco • First performance: Milan, Scala, 15 Feb 1845 • Alzira • First performance: Naples, S Carlo, 12 Aug 1845 • Macbeth • First performance: Florence, Pergola, 14 March 1847 • I masnadieri • First performance: London, Her Majesty’s, 22 July 1847 • Jérusalem • First performance: Paris, Opéra, 26 Nov 1847 • Il Corsaro • First performance: Trieste, Grande, 25 October 1848 • La battaglia di Legnano • First performance: Rome, Argentina, 27 Jan 1849 • Luisa Miller • First performance: Naples, S Carlo, 8 Dec 1848 • Stiffelio • First performance: Trieste, Grnade, 16 Nov 1850; autograph used for Aroldo, 1857 • Rigoletto • First performance: Venice, Fenice, 11 March 1851 • Il trovatore • First performance: Rome, Apollo, 19 Jan 1853 • La Traviata • First performance: Venice, Fenice, 6 March 1853 • Les vêpres siciliennes • First performance: Paris, Opéra, 13 June 1855 • Simon Boccanegra • First performance: Venice, Fenice, 12 March 1857, rev. version Milan, Scala, 24 March 1881 • Aroldo • First performance: Rimini, Nuovo, 16 Aug 1857 • Un ballo in maschera • First performance: Rome, Apollo, 17 Feb 1859 • La forza del destino • First performance: St Petersburg, Imperial, 10 Nov 1862, rev. version Milan, Scala, 27 Feb 1869 • Don Carlos • First performance: Paris, Opéra, 11 March 1867, rev. -

Che Il Pubblico Non Venga Defraudato Degli Spettacoli Ad Esso Promessi’

‘Che il pubblico non venga defraudato degli spettacoli ad esso promessi’ The Venetian Premiere of La traviata and Austria’s Imperial Administration in 1853* Axel Körner Historical myth (rather than scholarship) has it that the Austrians did eve- rything in their power to make lovers of opera in the Habsburgs’ Italian provinces feel miserable, and that works by Giuseppe Verdi in particular were viewed with a persistent deal of suspicion. An image of ruthless cen- sors, armed officers in the stalls and police spies in the corridors comes to mind.1 In the case of opera in Habsburg Venice, this idea was fostered by a tradition of politically motivated historiography that tended to justify Italians’ struggle for independence with the alleged despotism of Austrian rule in the region, closely linked to the image of the Empire as a ‘prison of nationalities’.2 That many of Italy’s greatest opera houses were built, and * The author is grateful for two helpful reader reports. Research for this article was supported by a generous grant of the Leverhulme Trust. 1 See for instance Giovanni GAVAZZENI, in ID., Armando TORNO, Carlo VITALI, O mia patria. Storia musicale del Risorgimento, tra inni, eroi e melodrammi (Milan: Dalai 2011), 60: «I palchi della Scala [...] erano occupati dalla soldataglia e dagli austriacanti». For a recent version of Verdi’s role in this tale see Angelo S. SABATINI, “Il contributo di Verdi alla formazione del mito del Risorgimento”, in Giuseppe Verdi e il Risorgi- mento, ed. Ester CAPUZZO, Antonio CASU, Angelo SABATINI (Soverelli Mannelli: Rubbettino 2014), 11-24.