Detroit's Field of Dreams: the Grassroots Preservation of Tiger Stadium Rebecca M

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TDD 2715 Woodward Avenue

RETAIL | 2715 WOODWARD AVENUE Retail 2715 WOODWARD AVENUE This new $70-million development includes an all-new, five-story, 127,000-square-foot building. The Detroit Medical Center (DMC) announced in June they will occupy approximately 50,000 square feet with a state-of-the-art sports medicine facility. In October, the award-winning law firm Warner Norcross + Judd, LLP announced they would occupy 30,000 square feet on the third floor. The Woodward fronting retail contains approximately 14,086 square feet. 14,086 SQ. FT. OF RETAIL #DistrictDetroit | DistrictDetroit.com Retail 2715 WOODWARD AVENUE #DistrictDetroit | DistrictDetroit.com The EXPERIENCE The District Detroit is a dynamic urban destination in the heart of Detroit. One that includes something for everyone — a dense neighborhood experience with a variety of developments alongside Detroit’s premiere sports and entertainment venues. Connecting downtown Detroit to growing nearby neighborhoods such as Midtown, Corktown and Brush Park, The District Detroit is having a dramatic economic impact on Detroit and is a driving catalyst of the city’s remarkable resurgence. The District Detroit is delivering $1.4 billion+ in new investment in Detroit including the new Little Caesars Arena, the Mike Ilitch School of Business at Wayne State University and Little Caesars world headquarters campus expansion. Additionally, new office, residential and retail spaces will continue to add momentum to Detroit’s amazing comeback for years to come. $1.4 BILLION+ IN NEW INVESTMENT A FIRST OF ITS KIND #DistrictDetroit -

Grand Marshals for Silver Bells in the City's Electric Light Parade

Grand Marshals for Silver Bells in the City’s Electric Light Parade announced Two players from the 1984 World Series Tigers team selected LANSING, MI — Silver Bells in the City is proud to announce the October 22, 2019 Grand Marshals of the 23rd Annual Electric Light Parade on November FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE 22nd as players from the 1984 Detroit Tigers World Series Championship team, Dan Petry and David Rozema. Silver Bells in the City is an annual celebration to kick off the holiday season in CONTACT downtown Lansing. This year’s theme is the ‘80s, commemorating the Mindy Biladeau, Director of Special 35th anniversary of Silver Bells, which began in 1984. Events & Programming Dan Petry is a former Major League Baseball pitcher for the Detroit LEPFA Tigers from 1979 to 1987 and from 1990 to 1991. He also pitched for 517-908-4037 the California Angels, Atlanta Braves, and Boston Red Sox. Petry [email protected] helped the Tigers win the 1984 World Series. He was elected to the American League All-Star team in 1985. He currently serves as a studio analyst for Detroit Tigers on Fox Sports Detroit. David Rozema [rose'-muh] hails from Grand Rapids, Michigan and is a former pitcher in Major League Baseball who played from 1977 through 1986 for the Detroit Tigers and Texas Rangers. He debuted in the major leagues at age 20 with the Detroit Tigers in 1977. Rozema finished his rookie season with a 15-7 record. In 1984, he played on the Tigers team that won the World Series. -

Download Preview

DETROIT TIGERS’ 4 GREATEST HITTERS Table of CONTENTS Contents Warm-Up, with a Side of Dedications ....................................................... 1 The Ty Cobb Birthplace Pilgrimage ......................................................... 9 1 Out of the Blocks—Into the Bleachers .............................................. 19 2 Quadruple Crown—Four’s Company, Five’s a Multitude ..................... 29 [Gates] Brown vs. Hot Dog .......................................................................................... 30 Prince Fielder Fields Macho Nacho ............................................................................. 30 Dangerfield Dangers .................................................................................................... 31 #1 Latino Hitters, Bar None ........................................................................................ 32 3 Hitting Prof Ted Williams, and the MACHO-METER ......................... 39 The MACHO-METER ..................................................................... 40 4 Miguel Cabrera, Knothole Kids, and the World’s Prettiest Girls ........... 47 Ty Cobb and the Presidential Passing Lane ................................................................. 49 The First Hammerin’ Hank—The Bronx’s Hank Greenberg ..................................... 50 Baseball and Heightism ............................................................................................... 53 One Amazing Baseball Record That Will Never Be Broken ...................................... -

From the Bullpen

1 FROM THE BULLPEN Official Publication of The Hot Stove League Eastern Nebraska Division 1992 Season Edition No. 11 September 22, 1992 Fellow Owners (sans Possum): We have been to the mountaintop, and we have seen the other side. And on the other side was -- Cooperstown. That's right, we thought we had died and gone to heaven. On our recent visit to this sleepy little hamlet in upstate New York, B.T., U-belly and I found a little slice of heaven at the Baseball Hall of Fame. It was everything we expected, and more. I have touched the plaque of the one they called the Iron Horse, and I have been made whole. The hallowed halls of Cooperstown provided spine-tingling memories of baseball's days of yore. The halls fairly echoed with voices and sounds from yesteryear: "Say it ain't so, Joe." "Can't anybody here play this game?" "Play ball!" "I love Brian Piccolo." (Oops, wrong museum.) "I am the greatest of all time." (U-belly's favorite.) "I should make more money than the president, I had a better year." "Where have you gone, Joe DiMaggio?" And of course: "I feel like the luckiest man alive." Hang on while I regain my composure. Sniff. Snort. Thanks. I'm much better From the Bullpen Edition No. 11 September 22, 1992 Page 2 now. If you ever get the chance to go to Cooperstown, take it. But give your wife your credit card and leave her at Macy's in New York City. She won't get it. -

SO.OO /////!Ij\\” Walsh, 2 in 3

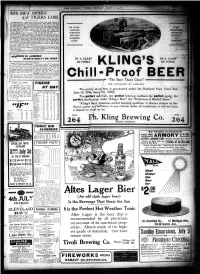

THE DETROIT TIMES: TRIDAY JULY I, i#:«. Page Seven SOX SW/ OFTEN AlO TIGERS LOSE The festive BoyL u le rae count to three run. until the end of White “ L* great Wly again Thursday uch the seventh when Walah, the aaslatant, ln. A sum total the sorrow of was sent Jo the It 1 of two hits In the eighth amounted t«mea the Chicago p*!, miriiii the ball, p ettfniba.tesd® clrcu,t to nothing, because-Crawford was fan- PH. KLING ■■■ EVERY twice , V|j for a «“« ™ - Infield and each homer cou uble ned and Morlarty popped an l,ul ®- (bi* fly Walsh itjll haae being occupied with the bases full. BREWING DEPARTMENT retails his old habit-of working ever):, opp° other day and working well. Stroud to ?h tbe al: COMPANY’S PERFECTLY started al,ed ancient Geo. Browne enjoyed a tlou to the *hltle»« 4de »°^ The r*. °“e big of batting when he made NEW AND hut not correctly t°ud revival EQUIPPED toning h a,,°" a hlt four singles and scored three times. long *• and ef , - ),tch •<*' the Detroit count down and cut loose a y‘ ln the Browne kept ENLARGED AND '-I. ond. ded hl ™ and one run by catching a liner from Stau- Summer. *ff was pulled out of h ct ive age In deep left center. The ball PLANT. OPERATED a £• •«f homer, until the Cobb • deslre to scheduled for a but Browne fifth v* managed to reach It after a hard Play center aiul*rt bo?b created an just error that nder on flrat fro,n run. -

Baseball Classics All-Time All-Star Greats Game Team Roster

BASEBALL CLASSICS® ALL-TIME ALL-STAR GREATS GAME TEAM ROSTER Baseball Classics has carefully analyzed and selected the top 400 Major League Baseball players voted to the All-Star team since it's inception in 1933. Incredibly, a total of 20 Cy Young or MVP winners were not voted to the All-Star team, but Baseball Classics included them in this amazing set for you to play. This rare collection of hand-selected superstars player cards are from the finest All-Star season to battle head-to-head across eras featuring 249 position players and 151 pitchers spanning 1933 to 2018! Enjoy endless hours of next generation MLB board game play managing these legendary ballplayers with color-coded player ratings based on years of time-tested algorithms to ensure they perform as they did in their careers. Enjoy Fast, Easy, & Statistically Accurate Baseball Classics next generation game play! Top 400 MLB All-Time All-Star Greats 1933 to present! Season/Team Player Season/Team Player Season/Team Player Season/Team Player 1933 Cincinnati Reds Chick Hafey 1942 St. Louis Cardinals Mort Cooper 1957 Milwaukee Braves Warren Spahn 1969 New York Mets Cleon Jones 1933 New York Giants Carl Hubbell 1942 St. Louis Cardinals Enos Slaughter 1957 Washington Senators Roy Sievers 1969 Oakland Athletics Reggie Jackson 1933 New York Yankees Babe Ruth 1943 New York Yankees Spud Chandler 1958 Boston Red Sox Jackie Jensen 1969 Pittsburgh Pirates Matty Alou 1933 New York Yankees Tony Lazzeri 1944 Boston Red Sox Bobby Doerr 1958 Chicago Cubs Ernie Banks 1969 San Francisco Giants Willie McCovey 1933 Philadelphia Athletics Jimmie Foxx 1944 St. -

March 2012 Prices Realized

HUGGINS AND SCOTT'S APRIL 5, 2012 PRICES REALIZED LOT# TITLE BIDS SALE PRICE* 1 1963-1968 Don Wert Game-Worn Detroit Tigers Road Uniform 16 $1,292.50 2 1968 World Series Detroit Tigers & St. Louis Cardinals Team Balls & Press Charms21 $1,175.00Full JSA 3 Don Wert Game-Used Glove 12 $646.25 4 Don Wert 1968 World Series Game-Issued Bat 14 $1,057.50 5 1968 American League All-Stars Team-Signed Ball With Mantle and Full JSA 22 $1,762.50 6 (3) 1962-1964 Detroit Tigers Team-Signed Baseball Run with Full JSAs 12 $763.75 7 (3) 1966-1970 Detroit Tigers Team-Signed Baseballs with Full JSA 8 $440.63 8 Detroit Tigers 1965 Team-Signed Bat and 1970 Team-Signed Ball - Full JSA 7 $470.00 9 1968-1970 Detroit Tigers Collection of (4) With 1968 Team-Signed Photo and10 World $558.13Series Black Bat 10 Don Wert 1968 All-Star Game Collection With Game-Issued Bat 9 $381.88 11 (3) Don Wert 1968 World Series Game-Issued Adirondack Bats 12 $411.25 12 Don Wert Minor League Lot of (3) With 1958 Valdosta Championship Ring 11 $323.13 13 Don Wert Tigers Reunion Lot of (6) With Uniforms and Multi-Signed Baseballs 6 $440.63 14 Don Wert Personal Awards Lot of (9) With 1965 BBWAA "Tiger of the Year" Plaque6 $270.25 15 Don Wert Memorabilia Balance of Collection With 1968 Team-Signed Photo and20 (10) $822.50Signed Baseballs 16 1911-14 D304 Brunners Bread Ty Cobb SGC 20 11 $6,462.50 17 1912 T227 Honest Long Cut Ty Cobb SGC 30 14 $2,702.50 18 (8) 1911-14 D304 General Baking Co. -

The 112Th World Series Chicago Cubs Vs. Cleveland Indians Saturday, October 29, 2016 Game 4 - 7:08 P.M

THE 112TH WORLD SERIES CHICAGO CUBS VS. CLEVELAND INDIANS SATURDAY, OCTOBER 29, 2016 GAME 4 - 7:08 P.M. (CT) FIRST PITCH WRIGLEY FIELD, CHICAGO, ILLINOIS 2016 WORLD SERIES RESULTS GAME (DATE RESULT WINNING PITCHER LOSING PITCHER SAVE ATTENDANCE Gm. 1 - Tues., Oct. 25th CLE 6, CHI 0 Kluber Lester — 38,091 Gm. 2 - Wed., Oct. 26th CHI 5, CLE 1 Arrieta Bauer — 38,172 Gm. 3 - Fri., Oct. 28th CLE 1, CHI 0 Miller Edwards Allen 41,703 2016 WORLD SERIES SCHEDULE GAME DAY/DATE SITE FIRST PITCH TV/RADIO 4 Saturday, October 29th Wrigley Field 8:08 p.m. ET/7:08 p.m. CT FOX/ESPN Radio 5 Sunday, October 30th Wrigley Field 8:15 p.m. ET/7:15 p.m. CT FOX/ESPN Radio Monday, October 31st OFF DAY 6* Tuesday, November 1st Progressive Field 8:08 p.m. ET/7:08 p.m. CT FOX/ESPN Radio 7* Wednesday, November 2nd Progressive Field 8:08 p.m. ET/7:08 p.m. CT FOX/ESPN Radio *If Necessary 2016 WORLD SERIES PROBABLE PITCHERS (Regular Season/Postseason) Game 4 at Chicago: John Lackey (11-8, 3.35/0-0, 5.63) vs. Corey Kluber (18-9, 3.14/3-1, 0.74) Game 5 at Chicago: Jon Lester (19-5, 2.44/2-1, 1.69) vs. Trevor Bauer (12-8, 4.26/0-1, 5.00) SERIES AT 2-1 CUBS AT 1-2 This is the 87th time in World Series history that the Fall Classic has • This is the eighth time that the Cubs trail a best-of-seven stood at 2-1 after three games, and it is the 13th time in the last 17 Postseason series, 2-1. -

An Analysis of the American Outdoor Sport Facility: Developing an Ideal Type on the Evolution of Professional Baseball and Football Structures

AN ANALYSIS OF THE AMERICAN OUTDOOR SPORT FACILITY: DEVELOPING AN IDEAL TYPE ON THE EVOLUTION OF PROFESSIONAL BASEBALL AND FOOTBALL STRUCTURES DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Chad S. Seifried, B.S., M.Ed. * * * * * The Ohio State University 2005 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor Donna Pastore, Advisor Professor Melvin Adelman _________________________________ Professor Janet Fink Advisor College of Education Copyright by Chad Seifried 2005 ABSTRACT The purpose of this study is to analyze the physical layout of the American baseball and football professional sport facility from 1850 to present and design an ideal-type appropriate for its evolution. Specifically, this study attempts to establish a logical expansion and adaptation of Bale’s Four-Stage Ideal-type on the Evolution of the Modern English Soccer Stadium appropriate for the history of professional baseball and football and that predicts future changes in American sport facilities. In essence, it is the author’s intention to provide a more coherent and comprehensive account of the evolving professional baseball and football sport facility and where it appears to be headed. This investigation concludes eight stages exist concerning the evolution of the professional baseball and football sport facility. Stages one through four primarily appeared before the beginning of the 20th century and existed as temporary structures which were small and cheaply built. Stages five and six materialize as the first permanent professional baseball and football facilities. Stage seven surfaces as a multi-purpose facility which attempted to accommodate both professional football and baseball equally. -

DETROIT BUSINESS MAIN 10-02-06 a 1 CDB.Qxd

DETROIT BUSINESS MAIN 10-02-06 A 1 CDB 9/29/2006 6:26 PM Page 1 ® http://www.crainsdetroit.com Vol. 22, No. 40 OCTOBER 2 – 8, 2006 $1.50 a copy; $59 a year ©Entire contents copyright 2006 by Crain Communications Inc. All rights reserved THIS JUST IN Grand Prix Redico buys former Compuware HQ Redico L.L.C. was in the process of closing Friday on the purchase of the for- return revs mer Compuware Corp. head- quarters in Farmington Hills. Redico plans to lease a large portion of the build- ing at 31440 Northwestern Hwy. to Trott & Trott P.C., a tourism push law firm focused on resi- dential mortgage foreclo- sures, bankruptcy and re- lated specialties. Trott & Events drive momentum Trott President and CEO REBECCA COOK David Trott confirmed the BY BRENT SNAVELY Workers at U.S. Steel’s Great Lakes Works plant in Ecorse walk through the building where CRAIN’S DETROIT BUSINESS deal late Friday. molten iron is converted to giant steel slabs that weigh 25 tons or more. The complex, built in As news leaked out Thursday that the Grand Prix 1987, includes the 190,000- would be returning to Detroit, six cruise ship representa- square-foot headquarters tives were meeting with the Detroit Metro Convention & Vis- and a more than 40,000- itors Bureau to showcase Detroit as a potential port for ad- square-foot annex with ditional Great Lakes ships to dock. health club, cafeteria and Although those executives have not yet made any deci- day-care center space. sions, the bureau said the timing of the Grand Prix an- Trott said the law firm nouncement was perfect. -

The 112Th World Series Chicago Cubs Vs

THE 112TH WORLD SERIES CHICAGO CUBS VS. CLEVELAND INDIANS SUNDAY, OCTOBER 30, 2016 GAME 5 - 7:15 P.M. (CT) FIRST PITCH WRIGLEY FIELD, CHICAGO, ILLINOIS 2016 WORLD SERIES RESULTS GAME (DATE RESULT WINNING PITCHER LOSING PITCHER SAVE ATTENDANCE Gm. 1 - Tues., Oct. 25th CLE 6, CHI 0 Kluber Lester — 38,091 Gm. 2 - Wed., Oct. 26th CHI 5, CLE 1 Arrieta Bauer — 38,172 Gm. 3 - Fri., Oct. 28th CLE 1, CHI 0 Miller Edwards Allen 41,703 Gm. 4 - Sat., Oct. 29th CLE 7, CHI 2 Kluber Lackey — 41,706 2016 WORLD SERIES SCHEDULE GAME DAY/DATE SITE FIRST PITCH TV/RADIO 5 Sunday, October 30th Wrigley Field 8:15 p.m. ET/7:15 p.m. CT FOX/ESPN Radio Monday, October 31st OFF DAY 6* Tuesday, November 1st Progressive Field 8:08 p.m. ET/7:08 p.m. CT FOX/ESPN Radio 7* Wednesday, November 2nd Progressive Field 8:08 p.m. ET/7:08 p.m. CT FOX/ESPN Radio *If Necessary 2016 WORLD SERIES PROBABLE PITCHERS (Regular Season/Postseason) Game 5 at Chicago: Jon Lester (19-5, 2.44/2-1, 1.69) vs. Trevor Bauer (12-8, 4.26/0-1, 5.00) Game 6 at Cleveland (if necessary): Josh Tomlin (13-9, 4.40/2-0/1.76) vs. Jake Arrieta (18-8, 3.10/1-1, 3.78) SERIES AT 3-1 CUBS AND INDIANS IN GAME 5 This marks the 47th time that the World Series stands at 3-1. Of • The Cubs are 6-7 all-time in Game 5 of a Postseason series, the previous 46 times, the team leading 3-1 has won the series 40 including 5-6 in a best-of-seven, while the Indians are 5-7 times (87.0%), and they have won Game 5 on 26 occasions (56.5%). -

The Irish in Baseball ALSO by DAVID L

The Irish in Baseball ALSO BY DAVID L. FLEITZ AND FROM MCFARLAND Shoeless: The Life and Times of Joe Jackson (Large Print) (2008) [2001] More Ghosts in the Gallery: Another Sixteen Little-Known Greats at Cooperstown (2007) Cap Anson: The Grand Old Man of Baseball (2005) Ghosts in the Gallery at Cooperstown: Sixteen Little-Known Members of the Hall of Fame (2004) Louis Sockalexis: The First Cleveland Indian (2002) Shoeless: The Life and Times of Joe Jackson (2001) The Irish in Baseball An Early History DAVID L. FLEITZ McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers Jefferson, North Carolina, and London LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGUING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA Fleitz, David L., 1955– The Irish in baseball : an early history / David L. Fleitz. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-7864-3419-0 softcover : 50# alkaline paper 1. Baseball—United States—History—19th century. 2. Irish American baseball players—History—19th century. 3. Irish Americans—History—19th century. 4. Ireland—Emigration and immigration—History—19th century. 5. United States—Emigration and immigration—History—19th century. I. Title. GV863.A1F63 2009 796.357'640973—dc22 2009001305 British Library cataloguing data are available ©2009 David L. Fleitz. All rights reserved No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying or recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. On the cover: (left to right) Willie Keeler, Hughey Jennings, groundskeeper Joe Murphy, Joe Kelley and John McGraw of the Baltimore Orioles (Sports Legends Museum, Baltimore, Maryland) Manufactured in the United States of America McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers Box 611, Je›erson, North Carolina 28640 www.mcfarlandpub.com Acknowledgments I would like to thank a few people and organizations that helped make this book possible.