Brachial-Ankle Pulse Wave Velocity and Metabolic Syndrome in a Japanese Population: the Minoh Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Considerable Scatter in the Relationship Between Left Atrial

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Considerable scatter in the relationship between left atrial volume and pressure in heart failure with preserved left ventricular ejection fraction Shiro Hoshida 1*, Tetsuya Watanabe1, Yukinori Shinoda1, Tomoko Minamisaka1, Hidetada Fukuoka1, Hirooki Inui1, Keisuke Ueno1, Takahisa Yamada2, Masaaki Uematsu3, Yoshio Yasumura4, Daisaku Nakatani5, Shinichiro Suna5, Shungo Hikoso5, Yoshiharu Higuchi6, Yasushi Sakata5 & Osaka CardioVascular Conference (OCVC) Investigators† The index for a target that can lead to improved prognoses and more reliable therapy in each heterogeneous patient with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) remains to be defned. We examined the heterogeneity in the cardiac performance of patients with HFpEF by clarifying the relationship between the indices of left atrial (LA) volume (LAV) overload and pressure overload with echocardiography. We enrolled patients with HFpEF (N = 105) who underwent transthoracic echocardiography during stable sinus rhythm. Relative LAV overload was evaluated using the LAV index or stroke volume (SV)/LAV ratio. Relative LA pressure overload was estimated using E/e’ or the afterload-integrated index of left ventricular (LV) diastolic function: diastolic elastance (Ed)/arterial elastance (Ea) ratio = (E/e’)/(0.9 × systolic blood pressure). The logarithmic value of the N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide was associated with SV/LAV (r = −0.214, p = 0.033). The pulmonary capillary wedge pressure was positively correlated to Ed/Ea (r = 0.403, p = 0.005). SV/LAV was negatively correlated to Ed/Ea (r = −0.292, p = 0.002), with no observed between-sex diferences. The correlations between the LAV index and E/e’ and Ed/Ea and between SV/LAV and E/e’ were less prominent than the abovementioned relationships. -

Essentials for Living in Osaka (English)

~Guidebook for Foreign Residents~ Essentials for Living in Osaka (English) Osaka Foundation of International Exchange October 2018 Revised Edition Essentials for Living in Osaka Table of Contents Index by Category ⅠEmergency Measures ・・・1 1. Emergency Telephone Numbers 2. In Case of Emergency (Fire, Sudden Sickness and Crime) Fire; Sudden Illness & Injury etc.; Crime Victim, Phoning for Assistance; Body Parts 3. Precautions against Natural Disasters Typhoons, Earthquakes, Collecting Information on Natural Disasters; Evacuation Areas ⅡHealth and Medical Care ・・・8 1. Medical Care (Use of medical institutions) Medical Care in Japan; Medical Institutions; Hospital Admission; Hospitals with Foreign Language Speaking Staff; Injury or Sickness at Night or during Holidays 2. Medical Insurance (National Health Insurance, Nursing Care Insurance and others) Medical Insurance in Japan; National Health Insurance; Latter-Stage Elderly Healthcare Insurance System; Nursing Care Insurance (Kaigo Hoken) 3. Health Management Public Health Center (Hokenjo); Municipal Medical Health Center (Medical Care and Health) Ⅲ Daily Life and Housing ・・・16 1. Looking for Housing Applying for Prefectural Housing; Other Public Housing; Looking for Private Housing 2. Moving Out and Leaving Japan Procedures at Your Old Residence Before Moving; After Moving into a New Residence; When You Leave Japan 3. Water Service Application; Water Rates; Points of Concern in Winter 4. Electricity Electricity in Japan; Application for Electrical Service; Payment; Notice of the Amount of Electricity Used 5. Gas Types of Gas; Gas Leakage; Gas Usage Notice and Payment Receipt 6. Garbage Garbage Disposal; How to Dispose of Other Types of Garbage 7. Daily Life Manners for Living in Japan; Consumer Affairs 8. When You Face Problems in Life Ⅳ Residency Management System・Basic Resident Registration System for Foreign Nationals・Marriage・Divorce ・・・27 1. -

What Is Osaka University Doing in ASEAN Countries?

Osaka University ASEAN Center for Academic Initiatives Contact address: Room C, 10th Floor, Serm-Mit Tower, Sukhumvit 21 (Soi Asok), Klongtoey-nua, Wattana, Bangkok 10110, Thailand http://www.bangkok.overseas.osaka-u.ac.jp/ Osaka University was founded in 1931 as the 6th imperial university of Japan through strong demand from the business and government sectors of Osaka, as well as the people of Osaka City and Prefecture. Now Osaka University holds 11 schools,16 graduate schools and 25 research centers and institutes with 15,250 undergraduate and 8,054 graduate students including 2,480 international students and 3,541 full-time academic and 3,113 full- time non-academic staff. It also has 4 libraries and 2 university hospitals; 3 campuses in Suita, Toyonaka, and Minoh. What is Osaka University doing in ASEAN countries? ASEAN Center for Academic Initiatives is one of the four overseas centers of Osaka University. The mission is to bridge Osaka U with ASEAN universities and academics, and to encourage “study in Osaka University” to ASEAN students. International Center for Biotechnology operates the Collaborative Research Center for Bioscience and Biotechnology in Mahidol University to promote joint researches with Thai universities such as CU, MU, KU and KMUTT, and offers the international educational programs under the support of Japanese Government, UNESCO and Thai universities. Research Institute for Microbial Diseases operates Thailand-Japan Research Collaboration Center on Emerging and Re-emerging Infections (RCC-ERI) under the Japanese national project. RCC-ERI carries out the qualified researches on infectious bacteria and viruses specific in tropical region. It has also research laboratories in Mahidol University. -

Urban Renaissance Agency

Profile of UR Greetings The Urban Renaissance Agency (UR), established in 1955 as the Japan What UR Can Do Housing Corporation, has been tackling a variety of urban issues for over half a century. President UR wants to build attractive cities that will lure people from all over the world. Masahiro NAKAJIMA We want to create an environment that is gentle on the elderly, conducive The agency currently implements a variety of initiatives in proactively addressing vital social issues, such as the falling birthrate, aging society to raising children, and gives everyone peace of mind. There is a lot that Urban and environmental problems, based on the agency’s mission of “creating Renaissance Agency can do in aiming to build cities that let people shine. cities of beauty, safety, and comfort where people can shine.” In the urban rejuvenation field, we coordinate conceptual planning and Urban Rejuvenation Field requirements, as well as collaborate with other partners to make large cities more attractive, strengthen international competitiveness, bolster We will promote urban renewal in cooperation with private businesses and local authorities the disaster-resistance of densely built-up areas, and revitalize regional to strengthen the international competitiveness of cities, improve densely built-up areas, cities. and implement other meaningful projects to promote urban rejuvenation. Moreover, in the living environment field, we carry out proper maintenance and management of UR rental housing throughout the country to ensure peace of mind for our customers. We are also promoting the establishment of housing and communities that will Living Environment Field ensure safety and health across all generations by using and renewing We carry out proper management of around 740,000 houses and apartment flats to existing housing stock, and turning them into community medical and provide comfortable living environments, while also functioning as a housing safety net for welfare centers, for example, by establishing facilities to handle the the elderly and people raising children. -

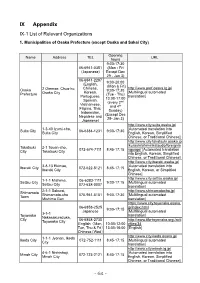

IX Appendix IX-1 List of Relevant Organizations

IX Appendix IX-1 List of Relevant Organizations 1. Municipalities of Osaka Prefecture (except Osaka and Sakai City) Opening Name Address TEL URL hours 9:00-17:30 06-6941-0351 (Mon - Fri (Japanese) Except Dec 29 - Jan 3) 06-6941-2297 9:00-20:00 (English, (Mon & Fri) Chinese, http://www.pref.osaka.lg.jp/ Osaka 2 Otemae, Chuo-ku, 9:00-17:30 Korean, [Multilingual automated Prefecture Osaka City (Tue - Thu) Portuguese, translation] 13:00-17:00 Spanish, (every 2nd Vietnamese, and 4th Filipino, Thai, Sunday) Indonesian, (Except Dec Nepalese and 29- Jan 3) Japanese) http://www.city.suita.osaka.jp/ 1-3-40 Izumi-cho, [Automated translation into Suita City 06-6384-1231 9:00-17:30 Suita City English, Korean, Simplified Chinese, or Traditional Chinese] http://www.city.takatsuki.osaka.jp /kurashi/shiminkatsudo/foreignla Takatsuki 2-1 Touen-cho, 072-674-7111 8:45-17:15 nguage/ [Automated translation City Takatsuki City into English, Korean, Simplified Chinese, or Traditional Chinese] http://www.city.ibaraki.osaka.jp/ 3-8-13 Ekimae, [Automated translation into Ibaraki City 072-622-8121 8:45-17:15 Ibaraki City English, Korean, or Simplified Chinese] http://www.city.settsu.osaka.jp/ 1-1-1 Mishima, 06-6383-1111 Settsu City 9:00-17:15 [Multilingual automated Settsu City 072-638-0007 translation] 2-1-1 Sakurai, http://www.shimamotocho.jp/ Shimamoto Shimamoto-cho 075-961-5151 9:00-17:30 [Multilingual automated Town Mishima Gun translation] https://www.city.toyonaka.osaka. 06-6858-2525 jp/index.html 9:00-17:15 Japanese [Multilingual automated 3-1-1 Toyonaka -

Summary of Family Membership and Gender by Club MBR0018 As of June, 2009

Summary of Family Membership and Gender by Club MBR0018 as of June, 2009 Club Fam. Unit Fam. Unit Club Ttl. Club Ttl. District Number Club Name HH's 1/2 Dues Females Male TOTAL District 335 B 23732 ARIDA 0 0 0 48 48 District 335 B 23733 DAITO 0 0 0 46 46 District 335 B 23734 FUJIIDERA 0 0 0 26 26 District 335 B 23735 HIGASHI OSAKA FUSE 0 0 3 30 33 District 335 B 23736 HIGASHI OSAKA CHUO 0 0 0 21 21 District 335 B 23737 HIGASHI OSAKA KIKUSUI 0 0 0 38 38 District 335 B 23738 GOBO 0 0 0 51 51 District 335 B 23739 HABIKINO 0 0 0 42 42 District 335 B 23740 HASHIMOTO 0 0 0 32 32 District 335 B 23741 HIGASHI OSAKA APOLLO 0 0 0 20 20 District 335 B 23742 HIRAKATA 0 0 0 73 73 District 335 B 23743 HIGASHI OSAKA 0 0 1 38 39 District 335 B 23744 IBARAKI 0 0 0 92 92 District 335 B 23745 IKEDA 0 0 0 55 55 District 335 B 23746 ITO KOYASAN L C 0 0 0 32 32 District 335 B 23747 IZUMIOSAKA 0 0 0 27 27 District 335 B 23748 IZUMI OTSU 0 0 0 69 69 District 335 B 23749 IZUMISANO 0 0 0 26 26 District 335 B 23750 IZUMISANO CHUO 0 0 0 35 35 District 335 B 23751 KADOMA 0 0 0 20 20 District 335 B 23752 KAINAN 0 0 0 30 30 District 335 B 23753 KAIZUKA 0 0 0 34 34 District 335 B 23754 KAWACHINAGANO 1 0 2 34 36 District 335 B 23755 HIGASHI OSAKA KAWACHI 0 0 2 25 27 District 335 B 23756 KASHIWARA 0 0 0 68 68 District 335 B 23758 KATSUURA 0 0 0 23 23 District 335 B 23759 KISHIWADA CHIKIRI 0 0 0 44 44 District 335 B 23760 KISHIWADA 0 0 0 45 45 District 335 B 23761 KISHIWADA CHUO 0 0 2 55 57 District 335 B 23763 KONGO 1 1 0 28 28 District 335 B 23764 KUSHIMOTO 0 0 2 24 -

IX-3 Health and Medical Care

IX-3 Health and Medical Care 1. Emergency Medical Clinics (Service available only in Japanese. It is recommended that you bring along someone competent in Japanese.) Int Internal Ped Pediatrics Medicine Sur General Den Dentistry Surgery Oph Ophthalmology Oto Otolaryngology Ort Orthopedics ※ You can find more information using Osaka Medical Facilities Information System search enging. (https://www.mfis.pref.osaka.jp/apqq/qq/men/pwtpmenult01.aspx) Town Facility Name Address Tel Reception Hours Suita Municipal 19-2 Deguchi-cho, Sun, Holidays, Year-end Suita Emergency Clinic Suita 06-6339-2271 & New Year Int Ped Sur Den 9:30-11:30, 13:00-16:30 Weeknights (Int・Ped・Sur)20:30-6:30 Osaka Mishima Sat (Int・Ped・Sur) Emergency 14:30-6:30 11-1 Medical Center/ Sun and Holidays Minami-akutagawa Shimamoto & Takatsuki 072-683-9999 cho, Takatsuki (Int・Ped・Sur) Takatsuki Shimamoto 9:30-11:30, 13:30-16:30, Emergency Clinic 18:30-6:30 Int Ped Sur Den Sun and Holidays (Den) 9:30-11:30, 13:30-16:30 Weeknights Ibaraki Municipal (Int) 21:00-23:30 Public Health and Sat (Int) 17:00-6:30 Medical Center Emergency Clinic Sun and Holidays 3-13-5 Kasuga, Ibaraki Int. Den 072-625-7799 (Int) Ibaraki 10:00-11:30, 13:00-16:30, *For pediatrics, 18:00-6:30 visit Takatsuki/ Sun and Holidays Shimamoto Emergency Clinic (Den) 10:00-11:30, 13:00-16:30 Settsu Municipal Sun, Holidays, Year-end Emergency 32-19 Kohroen, Settsu 072-633-1171 & New Year Pediatric Clinic Settsu Ped 10:00-11:30, 13:30-16:30 Clinic of Toyonaka Sun, Holidays, Aug 14/15, Municipal Health 2-6-1 Uenosaka, 06-6848-1661 -

Safety Guide H4 Safety Guide H1

Safety Guide_h4 Safety Guide_h1 Beep! Beep! If the gas/CO alarm sounds or your think you can smell gas, immediately call the Osaka Gas Gas Leak Emergency Number! Flash! Reference Outside... In shared areas... In store… Safety Guide copy ● INDEX ● 02 Take care in the kitchen 04 Take care in bakeries or patisseries 06 Take care in the office 07 Take care at barbers, hair salons and dry cleaning stores 08 For your peace of mind 1 1 How to restore your intelligent gas meter Call the Osaka Gas Gas Leak Emergency Number immediately. 12 Safe gas taps and connectors Business-use gas safety system Osaka Department: 2-37 Chiyozaki 3-chome-minami, Nishi-ku, Osaka 550-0023 Gas Leak Emergency Number 14 ● Area: Osaka-shi 0120(0)19424 South Department: 2-2-19 Sumiyoshibashi-cho, Sakai-ku, Sakai-shi 590-0973 ● Area: Sakai-shi, Izumiotsu-shi, Izumi-shi, Kishiwada-shi, Kaizuka-shi, Izumisano-shi, Gas Leak Emergency Number Tondabayashi-shi, Matsubara-shi, Fujiidera-shi, Takaishi-shi, Habikino-shi, Sennan-shi, Kawachinagano-shi, Hannan-shi, Tadaoka-cho, Osakasayama-shi, Tajiri-cho, Kumato- 0120(3)19424 ri-cho, Kanan-cho, Misaki-cho, Taishi-cho, Wakayama-shi, Kainan-shi, Iwade-shi North East Department: 2-3-17 Inaba, Higashiosaka 578-0925 ● Area: Suita-shi, Toyonaka-shi, Minoh-shi, Ikeda-shi, Takatsuki-shi, Ibaraki-shi, Settsu-shi, Shimamoto-cho, Hirakata-shi, Higashiosaka-shi, Yao-shi, Kashiwara-shi, Gas Leak Emergency Number Daito-shi, Shijonawate-shi, Neyagawa-shi, Moriguchi-shi, Kadoma-shi, Katano-shi, Yawata-shi, Kyotanabe-shi, Nara-shi, Yamato Takada-shi, -

Frontierlab@Osakau

FrontierLab@OsakaU Scientific Empowerment Program for International Students INTRODUCTION Osaka University is at the forefront of Scientific technological innovation in Japan and is recognized as one of the leading Empowerment science universities in the world. FrontierLab@OsakaU of Osaka Program for University is a program designed to nurture creative competency in International students by offering a wide range of Students potential research directions and emphasizing hands-on laboratory experience. It is specifically created for international students seeking to upgrade vital research and analytical skills. Applications from both undergraduate and graduate science and engineering majors are welcome. !1 Why FrontierLab@OsakaU? Close Supervision by Top Scientists Learning in the Community of Practice in the World The Japanese tradition of the spirit of Osaka University has long been creation is very much alive in the frontier recognized for its world-class research research laboratory. Participants will output and quality training for up-and- have a first-hand experience of the coming researchers. Each participant in Japanese spirit of invention and the FrontierLab Program will be assigned breakthrough through laboratory to an internationally renowned research experiments at Osaka University. group, and thematic studies will be conducted under the close supervision of the faculty who are top in the field. Interactive and Experiential Learning FrontierLab@OsakaU characterizes itself with small group discussions and one-to- one supervision by faculty, which enable participants to experience interactive and Hands-on experiential learning. Participants select Experience of a topic from basic to applied to the most challenging and cutting-edge and Internationally conduct experiments through peer consultation, group work and interactive Renowned discussions. -

E N G L I S H

Welcome to City Map and Public Be Prepared for Useful Information Toyonaka City Transportation Accidents and for Foreign Citizens Emergencies Toyonaka Your Life in In Case of Illness Pregnancy, International Center Toyonaka Child-rearing, Education Procedures Related List of Facilities Information & to Your Daily Life Consultation Services in Different Languages E n g l i s h Contents ■ Welcome to Toyonaka City ······························· P.1 ■ City Map and Public Transportation ······················ P.2 Hankyu Railway, Kita-Osaka Kyuko Railway (Osaka Municipal Transportation Bureau), Monorail, Airport Limousine 1 Be Prepared for Accidents and Emergencies ····················· P.3 □1 -1 Disaster Prevention (1) Earthquake (2) Typhoon (3) Flood (4) In Case of Disaster and Collecting Information (5) Alert-level Warning System in Case of Disasters □1 -2 Emergency Calls (1)Police (2)Fire/Sudden Illness/Accidents 2 Useful Information for Foreign Citizens ················· P.10 □2 -1 Japanese Classes within Toyonaka City □2 -2 Consultation Services in Different Languages (1) Toyonaka City Hall (2) Toyonaka International Center (3) Other Consultation Services in Different Languages □2 -3 Toyonaka International Center (1) Consultation Service for Foreign Residents (2) Japanese Classes (3) Newsletter (4) Projects at the International Center (5) Fureai Koryu Salon □2 -4 How to get Information for Foreign Residents (1) Koho Toyonaka (2) Newsletter for Foreigners: “Toyonaka City Monthly Information” (3) Toyonaka City Mail: Information Delivery -

Summary of Family Membership and Gender by Club MBR0018 As of December, 2009 Club Fam

Summary of Family Membership and Gender by Club MBR0018 as of December, 2009 Club Fam. Unit Fam. Unit Club Ttl. Club Ttl. District Number Club Name HH's 1/2 Dues Females Male TOTAL District 335 B 23732 ARIDA 0 0 0 48 48 District 335 B 23733 DAITO 0 0 3 48 51 District 335 B 23734 FUJIIDERA 0 0 0 30 30 District 335 B 23735 HIGASHI OSAKA FUSE 0 0 4 29 33 District 335 B 23736 HIGASHI OSAKA CHUO 0 0 2 19 21 District 335 B 23737 HIGASHI OSAKA KIKUSUI 0 0 0 36 36 District 335 B 23738 GOBO 0 0 1 51 52 District 335 B 23739 HABIKINO 0 0 0 43 43 District 335 B 23740 HASHIMOTO 0 0 0 33 33 District 335 B 23741 HIGASHI OSAKA APOLLO 0 0 0 10 10 District 335 B 23742 HIRAKATA 0 0 0 71 71 District 335 B 23743 HIGASHI OSAKA 0 0 1 39 40 District 335 B 23744 IBARAKI 0 0 0 94 94 District 335 B 23745 IKEDA 0 0 0 53 53 District 335 B 23746 ITO KOYASAN L C 0 0 0 32 32 District 335 B 23747 IZUMIOSAKA 0 0 0 24 24 District 335 B 23748 IZUMI OTSU 0 0 0 74 74 District 335 B 23749 IZUMISANO 0 0 0 26 26 District 335 B 23750 IZUMISANO CHUO 0 0 0 36 36 District 335 B 23751 KADOMA 0 0 0 20 20 District 335 B 23752 KAINAN 0 0 0 31 31 District 335 B 23753 KAIZUKA 0 0 0 26 26 District 335 B 23754 KAWACHINAGANO 0 0 3 34 37 District 335 B 23755 HIGASHI OSAKA KAWACHI 0 0 2 24 26 District 335 B 23756 KASHIWARA 0 0 0 65 65 District 335 B 23758 KATSUURA 0 0 0 24 24 District 335 B 23759 KISHIWADA CHIKIRI 0 0 0 42 42 District 335 B 23760 KISHIWADA 0 0 0 43 43 District 335 B 23761 KISHIWADA CHUO 0 0 2 51 53 District 335 B 23763 KONGO 1 1 0 28 28 District 335 B 23764 KUSHIMOTO 0 0 2 -

Minoh City Household Garbage Guide

(Please keep this guide) Minoh City Household Garbage Guide Your collection days Twice a Burnable garbage Every week on and week Every month PET bottles, unburnable garbage, Twice a week number and on dangerous garbage, oversized garbage month Every month Twice a Empty cans and bottles week number and on month ・Collection is not affected by public holidays. ・Around New Year's, there is a special schedule. Please check the December issue of the city magazine, "Momiji Dayori". ・Be sure to put garbage out in the designated area. (If you are unsure of where to put your garbage, please contact the Waste Management Division.) ※Apartment building owners, managers etc. are responsible for ensuring tenants are aware of the rules for proper disposal. PET bottles, unburnable garbage, dangerous garbage, and Collection Schdeule oversized garbage are collected on the same day Empty Burnable PET bottles, cans, unburnable,dangerous District garbage bottles and oversized garbage Be sure to put out your garbage Group A-1 before 9 a.m. on collection day Segawa, Hanjo n 1st/3rd Tuesday o i Enquiries t c Group A-2 e Sakura, Sakurai l l 1st/3rd 1st/3rd Friday ◆Regarding garbage collection A o Mon. & c p TEL . Wed. of Group A-3 W a s t e Management 072-729-2371 u s Sakuragaoka, Niina Thurs. r o 2nd/4th Tuesday Division FAX r 072-729-7337 u the h G weekly s r Mon.-Fri. (Incl. holidays)(Excl. Around New Year's) T Hakushima, Ishimaru, Nishijuku, Imamiya, Group A-4 u month . o n Semba-higashi, Onohara-nishi 2nd/4th Wednesday H 8:45-17:15 o M Gein, Aogein, Aoshinke, Saitoao-kita, Group A-5 Saitoao-minami 2nd/4th Friday ◆Regarding carry-in garbage Group B-1 Environmental TEL 072-729-4280 Hyakurakuso, Makiochi, Ina 1st/3rd Monday Clean Center FAX 072-728-3156 s Group B-2 r Tue.-Sat.