A Practical Introduction to the Dsm-5: Implementing The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sunderland Psychological Wellbeing Service Information for Referrers

Sunderland Psychological Wellbeing Service Information for Referrers Offering a range of psychological therapies across Sunderland. Call 0191 566 5454 or visit www.sunderlandiapt.co.uk A partnership between, Cumbria, Northumberland, Tyne and Wear NHS Foundation Trust, Sunderland Counselling Service, Sunderland Mind and Washington Mind Sunderland Psychological Wellbeing Service (SPWS) provides a range of therapeutic interventions delivered in Primary Care Centre’s, GP practices and community settings. Who is Sunderland Psychological Wellbeing Service for? The service is for people aged 16 years (who have completed Year 11) and over who present with mild to moderate depression and anxiety disorders, including: • Mild to moderate depression • Panic Disorder • Generalised Anxiety Disorder • Specific Phobias (GAD) • Body Dysmorphic Disorder • Stress/Work related stress (BDD) • Relationship difficulties • Obsessive Compulsive • Family stress Disorder (OCD) • Loss/Adjustment disorder • Coping with illness / • Post Traumatic Stress Disorder chronic conditions (PTSD) • Agoraphobia • Health Anxiety • Social Anxiety We also offer general mental health assessment and advice. If you have any doubt about the suitability of our service for your patient, our staff are happy to discuss this with you via our referral line on 0191 5665454. Services available Self Help Classes Self-help classes are weekly sessions for 4-5 weeks. We offer a wide range of self-help classes (lasting 60-90 minutes per class and running over a period of 3-5 weeks) including: Depression, Panic, Stress Control and Persistent Physical symptoms for people experiencing difficulties with pain and fatigue. Guided Self Help Individual work supported by a Psychological Wellbeing Practitioner delivered via telephone or on line consultation. Self-help materials are used to understand and manage problems such as depression, anxiety, stress, panic, OCD, social anxiety, low self-esteem and health anxiety. -

Gay, Lesbian, Transgender & Bisexual Individuals

Gay, Lesbian, Transgender & Bisexual Individuals Contributors: Christopher R. Martell, Ph.D., ABP, University of Washington & Private Practice Marsha Botzer, M. A., Ingersoll Gender Center Mark Williams, M.Div., and Dan Yoshimoto, M. S. University of Washington 205 A Review of the Literature As far back as 1935, Sigmund Freud wrote to the anxious mother of a homosexual son that: “Homosexuality is assuredly no advantage, but it is nothing to be ashamed of, no vice, no degradation, it cannot be classified as an illness…” (Freud, 1935 as cited in Bayer, 1987). Nevertheless, the American Psychiatric Association included homosexuality under the grouping of sociopath personality disturbances in the first edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Psychiatric Disorders (DSM-I, American Psychiatric Association, 1952). By the time of the second edition of the DSM (DSM-II, American Psychiatric Association, 1968), the diagnosis of homosexuality was moved under the general heading of sexual deviations. Alfred Kinsey and colleagues studied a group of American white males, and published data suggesting that for a certain percentage of the population was sexually stimulated by other males (Kinsey, Pomeroy, & Martin, 1948). Later, in 1953, Kinsey, Pomeroy, Martin, & Gebhard conducted similar research with females. Research was emerging in the 1950s, demonstrating that homosexuality, per se, did not constitute a mental disorder. The pioneering work of Evelyn Hooker (1957) demonstrated that homosexual males were similar to heterosexual males on tests of psychopathology. Homosexuality was removed from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Psychiatric Disorders in the third edition (DSM-III, American Psychiatric Association, 1980), but a diagnosis of ego-dystonic homosexuality was added. -

University of Michigan School of Social Work Syllabus

Course title: Interpersonal Practice with Families Course #/term: SW 623-003 Winter, 2020 Time. place Thursday 2:00-5:00pm 002 SSWB Credit hours: 3 Prerequisites: SW521 or permission of instructor Instructor: Ellen Yashinsky Chute, LMSW Pronouns: She, her, hers Contact info: Email: [email protected] Phone: 248-505-2011 You may expect a response within 24 hours Office: 3764 SSWB Office hours: by appointment 1. Course Statement a. Course description This course will build on the content presented in course SW 521 (i.e. Interpersonal Practice with Individuals, Families and Small Groups). This course will present a theoretical analysis of family functioning and integrate this analysis with social work practice. Broad definitions of "family" will be used, including extended families, unmarried couples, single parent families, gay or lesbian couples, adult siblings, "fictive kin," and other inclusive definitions. Along with theories and knowledge of family structure and process, guidelines and tools for engaging, assessing, and intervening with families will be introduced. The most recent social science theories and evidence will be employed in guiding family assessment and intervention. This course will cover all stages of the helping process with families (i.e. engagement, assessment, planning, evaluation, intervention, and termination). During these stages, client-worker differences will be taken into account including a range of diversity dimensions such as ability, age, class, color, culture, ethnicity, family structure, gender (including gender identity and gender expression), marital status, national origin, race, religion or spirituality, sex, and sexual orientation. Various theoretical approaches will be presented in order to help students understand family structure, communication patterns, and behavioral and coping repertoires. -

Pathways to Dialogue: the Work of Collaborative Therapists with Couplesi Mónica Sesma Vázquez México City, México

Sesma Vázquez Pathways to Dialogue: The Work of Collaborative Therapists with Couplesi Mónica Sesma Vázquez México City, México To hear is beautiful to those who listen. Egyptian proverb Since Collaborative Therapy is often described as a philosophical position or a stance and the literature on collaborative therapy does not provide any “recipes” or steps to follow, I was interested in talking to therapists to find out how they implement collaborative ideas in their practice, specifically in their work with couples. My curiosity started when I read that many therapists believe that couple‟s therapy is the hardest treatment modality and not many therapists included work with couples in their practice (Lebow, 2007). As a collaborative therapist I thought that my colleagues did work with couples, and that I worked with couple‟s too and my sense was we did not feel that couple‟s therapy was more difficult than our work with individuals or families. So I wanted to find out Abstract: The purpose of this study was to identify the what therapists thought about collaborative work with couples and premised that guide collaborative therapists in their efforts to how they actually did it. This was the generate dialogues in couples. The two main research beginning of my doctoral dissertation, questions were: How do therapists create dialogical processes which was a detailed qualitative study with couples? and what are the pathways to dialogue between that explored therapists‟ accounts of the three members of the conversation?., Several interviews the premisesii that guide their were accomplished, using a qualitative method to obtain the collaborative therapeutic work with perspective of 10 collaborative therapists in Mexico. -

Collaborative Therapy with Multi-Stressed Families Free

FREE COLLABORATIVE THERAPY WITH MULTI- STRESSED FAMILIES PDF William C. Madsen | 388 pages | 15 Mar 2007 | Guilford Publications | 9781593854348 | English | New York, United States Collaborative Therapy with Multi-stressed Families - William C. Madsen - Google книги William C. This volume describes an innovative approach to working with families who have not been well served by traditional mental health, social service, and medical systems. Critically examining many professional assumptions about "difficult" families, the book outlines clinical practices that facilitate a respectful, constructive, and effective therapeutic relationship. Highlighted are ways to engage reluctant clients, conduct nonpathologizing assessments, and help families develop communities of support. Of crucial importance, the author proposes that therapists move away from trying to identify Collaborative Therapy with Multi-stressed Families correct old problems. He focuses instead on how to support clients in envisioning desired futures and developing new lives. Including a wealth of compelling clinical material, the book raises important theoretical and political questions without becoming moralistic and promotes a strengths-based focus without romanticizing families or minimizing their difficulties. He has spent most of the last 20 years working in public sector mental health with "high-risk," multi-stressed families. Currently a provider of training and consultation to agencies and organizations, Dr. Madsen has developed and administered innovative programs that -

Tracey Foster Program Administrator

® Telephone ~ 1-866-653-2119 www.elitecme.com Dear Licensee: Georgia state rules allow you to complete 10 of your 40 required continuing education hours through home-study. It can be very difficult to find time in your busy schedule to complete your required continuing education.That is why we set out to create a home-study continuing education course that would not only be comprehensive, but also at a guaranteed low price. With this course book you can complete all 10 hours allowed through home-study for only $50. If you find a course with a lower price, just call us toll-free and we will beat it! Elite offers the very best in continuing education. Our company refund policy is satisfaction guaranteed or 100 percent refund. Once you review the course, go online to complete your testing at www.elitecme.com. Our secure online site allows you to immediately print out your certificate after you complete the course.We are rated A+ by the National Better Business Bureau Online Reliability Program. Should you have any questions, do not hesitate to contact us at our toll-free number: 1-866-653-2119. Sincerely, Tracey Foster Program Administrator I Elite Table of Contents Bullying in Children and Youth Chapter 1 (4 CE Hours ~ $24.00) ...........................................................................................Page 1 Final Examination Questions ...............................................................................Page 14 Early Attachment Theory: Research and Clinical Applications Chapter 2 (3 CE Hours ~ $18.00) ...........................................................................................Page -

Collaborative Recovery: an Integrative Model for Working with Individuals Who Experience Chronic and Recurring Mental Illness

University of Wollongong Research Online Faculty of Health and Behavioural Sciences - Papers (Archive) Faculty of Science, Medicine and Health 2005 Collaborative Recovery: An integrative model for working with individuals who experience chronic and recurring mental illness Lindsay G. Oades University of Wollongong, [email protected] Frank P. Deane University of Wollongong, [email protected] Trevor P. Crowe University of Wollongong, [email protected] Gordon Lambert University of Wollongong, [email protected] David Kavanagh University of Queensland See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/hbspapers Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons, Life Sciences Commons, Medicine and Health Sciences Commons, and the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Oades, Lindsay G.; Deane, Frank P.; Crowe, Trevor P.; Lambert, Gordon; Kavanagh, David; and Lloyd, Christopher: Collaborative Recovery: An integrative model for working with individuals who experience chronic and recurring mental illness 2005, 279-284. https://ro.uow.edu.au/hbspapers/1017 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] Collaborative Recovery: An integrative model for working with individuals who experience chronic and recurring mental illness Abstract Objectives: Recovery is an emerging movement in mental health. Evidence for recovery-based approaches is not well developed and approaches to implement recovery-oriented services are not well articulated. The collaborative recovery model (CRM) is presented as a model that assists clinicians to use evidencebased skills with consumers, in a manner consistent with the recovery movement. -

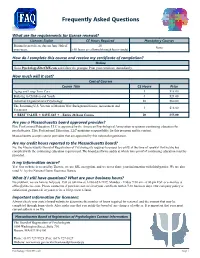

Frequently Asked Questions

Frequently Asked Questions What are the requirements for license renewal? Licenses Expire CE Hours Required Mandatory Courses Biennial renewals are due on June 30th of 20 None even years. (All hours are allowed through home-study) How do I complete this course and receive my certificate of completion? Online Go to Psychology.EliteCME.com and follow the prompts. Print your certificate immediately. How much will it cost? Cost of Courses Course Title CE Hours Price Aging and Long-Term Care 3 $18.00 Bullying in Children and Youth 4 $24.00 Industrial/Organizational Psychology 10 $60.00 The Returning U.S. Veteran of Modern War: Background Issues, Assessment and 3 $18.00 Treatment BEST VALUE SAVE $65 - Entire 20-hour Course 20 $55.00 Are you a Massachusetts board approved provider? Elite Professional Education, LLC is approved by the American Psychological Association to sponsor continuing education for psychologists. Elite Professional Education, LLC maintains responsibility for this program and its content. Massachusetts accepts course providers that are approved by this national organization. Are my credit hours reported to the Massachusetts board? No, the Massachusetts Board of Registration of Psychologists requires licensees to certify at the time of renewal that he/she has complied with the continuing education requirement. The board performs audits at which time proof of continuing education must be provided. Is my information secure? Yes! Our website is secured by Thawte, we use SSL encryption, and we never share your information with third-parties. We are also rated A+ by the National Better Business Bureau. What if I still have questions? What are your business hours? No problem, we are here to help you. -

Psychiatry at St Vincent’S Health and the University of Melbourne

WIT.0002.0044.0001 WITNESS STATEMENT OF PROFESSOR DAVID JONATHAN CASTLE I, Professor David Jonathan Castle, Consultant Psychiatrist at St Vincent’s Hospital Melbourne, of 41 Victoria Parade Fitzroy VIC 3065, say as follows: 1 I am a Professor of Psychiatry at St Vincent’s Health and the University of Melbourne. I am a former MRC Research Scholar at the South African Institute for Medical Research, MRC Research Fellow at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, and trained in both clinical research and psychiatry at Maudsley Hospital and Institute of Psychiatry in London. Attached to this statement and marked ‘DJC-1’ is a copy of my current curriculum vitae. 2 My clinical and research interests include schizophrenia and related disorders, and bipolar disorder. I served two years as Chair of the Victorian branch of the Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists and was an elected member of the Binational RANZCP Board from 2016 to 2018. I am currently a board member of both Mind Medicine Australia and the Mental Health Foundation of Australia. I am one of the founders of the Optimal Health Model currently under the auspice of Optimal Wellness Australia, in which I have a financial stake, hence I have a clear personal interest in that model, which I address in detail in this statement. 3 I make this statement on the basis of my own knowledge, save where otherwise stated. Where I make statements based on information provided by others, I believe such information to be true. 4 I am giving evidence to the Royal Commission into Victoria’s Mental Health System in my personal capacity. -

Group Therapy for Mood Disorders: a Review of the Clinical Effectiveness

TITLE: Group Therapy for Mood Disorders: A Review of the Clinical Effectiveness DATE: 09 November 2009 CONTEXT AND POLICY ISSUES: Mood disorders include bipolar disorder and depression. Bipolar disorder occurs in approximately 1% of the population and has high rate of relapse and suicide.1 Symptoms of major depressive disorder often persist despite antidepressant therapy2 and the disorder is often recurrent.3 Psychotherapy may have a role as adjunctive therapy to prevent relapse or to resolve residual symptoms in patients with mood disorders.1,4 This report will address the clinical effectiveness of group psychotherapy or psychoeducation in patients with mood disorders. RESEARCH QUESTION: What is the clinical effectiveness of group therapy interventions for the treatment of patients with mood disorders to improve functioning, health-related quality of life (HRQL), and reduce hospitalization? METHODS: A focused search (main concepts appeared in subject heading) was conducted in Medline and PsycINFO. A limited literature search was conducted on all other key health technology assessment resources, including PubMed in process, The Cochrane Library (Issue 3, 2009), University of York Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (CRD) databases, ECRI, EuroScan, international health technology agencies, and a focused Internet search. The search was limited to English language articles published between 2004 and September 2009. Filters were applied to limit the retrieval to health technology assessments, systematic reviews, meta-analyses, randomized controlled trials (RCTs), controlled clinical trials, and observational studies. Disclaimer: The Health Technology Inquiry Service (HTIS) is an information service for those involved in planning and providing health care in Canada. HTIS responses are based on a limited literature search and are not comprehensive, systematic reviews. -

Collaborative Relationships and Dialogic Conversations: Ideas for a Relationally Responsive Practice

PROCESS Collaborative Relationships and Dialogic Conversations: Ideas for a Relationally Responsive Practice HARLENE ANDERSON* To read this article in Spanish, please see the article’s Supporting Information on Wiley Online Library (wileyonlinelibrary.com/journal/famp). The author presents a set of philosophical assumptions that provide a different lan- guage for thinking about and responding to the persistent questions: “How can our therapy practices have relevance for people’s everyday lives in our fast changing world, what is this relevance, and who determines it?” “Why do some shapes of relationships and forms of talk engage while others alienate? Why do some invite possibilities and ways forward not imagined before and others imprison us?” The author then trans- lates the assumptions to inform a therapist’s philosophical stance: a way of being. Next, she discusses the distinguishing features of the stance and how it facilitates col- laborative relationships and dialogic conversations that offer fertile means to creative ends for therapists and their clients. Keywords: Collaborative Relationships; Dialogic Conversations; Philosophical Stance; Way of Being; Withness; Postmodern Therapy Fam Proc 51:8–24, 2012 s predicted when Harry Goolishian and I concluded our 1988 article Human Sys- Atems as Linguistic Systems, what seemed plausible ideas then have evolved over time. At that time we were immersed in exploring a language systems metaphor for our work, and had left behind mechanical cybernetic systems metaphors. No longer thinking of human systems as social systems defined by social organization, we viewed them as language systems distinguished by respective linguistic and commu- nicative markers. Since then the language systems metaphor, although important, had faded into the background as I continued to explore other organizing metaphors for my practice experiences. -

{TEXTBOOK} Cognitive Therapy of Substance Abuse

COGNITIVE THERAPY OF SUBSTANCE ABUSE PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Aaron T. Beck, Fred D. Wright, Cory F. Newman, Bruce S. Liese | 354 pages | 15 Mar 2001 | Guilford Publications | 9781572306592 | English | New York, United States Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Substance Use Disorders - Pinnacle Treatment Centers The evidence certainly exists to indicate cognitive therapies are effective in dealing with addictive behaviors. Traditional step groups, cognitive- behavioral therapies, and motivational interviewing have been found equally effective in the treatment of people with alcohol abuse problems American Psychological Association, One of the greatest advantages to the cognitive-behavioral therapies is that they are also appropriate in dealing with some of the mental health issues that may have been contributing factors in the onset of substance abuse. For those who are dual diagnosed, this is particularly important because of the stigmas concerning mental illness that can be found with those involved in the step programs. Ouimette, Finney, and Moos found similar results when comparing cognitive-behavioral therapy with step approaches to alcohol abuse treatment. However, the authors report that those individuals in the step program were more likely to remain abstinent one year following treatment as compared to those who were involved in a cognitive-behavioral therapy treatment modality. It is interesting to note that one of the distinct differences between the two approaches is that the step programs are free while most cognitive- behavioral therapies are financially driven and subject to financial constraints of state or locally funded programs, insurance companies, or health management organizations. Simple availability to resources could be a factor when apprising long-term outcomes in a non-research setting.