Escaping the Gilded Cage: User Created Content and Building the Metaverse

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Theescapist 055.Pdf

in line and everything will be just fine. two articles I fired up Noctis to see the Which, frankly, is about how many of us insanity for myself. That is the loneliest think to this day. With the exception of a game I’ve ever played. For those of you who fell asleep during very brave few. the classical mythology portion of your In response to “Development in a - Danjo Olivaw higher education, the stories all go like In this issue of The Escapist, we take a Vacuum” from The Escapist Forum: this: Some guy decides he no longer look at the stories of a few, brave souls As for the fact that thier isolation has In response to “Footprints in needs the gods, sets off to prove as in the game industry who, for better or been a benefit to them rather than a Moondust” from The Escapist Forum: much and promptly gets smacked down. worse, decided that they, too, were hindrance, that’s what I discussed with I’d just like to say this was a fantastic destined to make their dreams a reality. Oveur (Nathan Richardsson) while in article. I think I’ll have to read Olaf Prometheus, Sisyphus, Icarus, Odysseus, Some actually succeeded, while others Vegas earlier this year at the EVE the stories are full of men who, for crashed and burned. We in the game Gathering. The fact that Iceland is such whatever reason, believed that they industry may not have jealous, angry small country, with a very unique culture were not bound by the normal gods against which to struggle, but and the fact that most of the early CCP constraints of mortality. -

Game Developer Magazine

>> INSIDE: 2007 AUSTIN GDC SHOW PROGRAM SEPTEMBER 2007 THE LEADING GAME INDUSTRY MAGAZINE >>SAVE EARLY, SAVE OFTEN >>THE WILL TO FIGHT >>EXCLUSIVE INTERVIEW MAKING SAVE SYSTEMS FOR CHANGING GAME STATES HARVEY SMITH ON PLAYERS, NOT DESIGNERS IN PANDEMIC’S SABOTEUR POLITICS IN GAMES POSTMORTEM: PUZZLEINFINITE INTERACTIVE’S QUEST DISPLAY UNTIL OCTOBER 11, 2007 Using Autodeskodesk® HumanIK® middle-middle- Autodesk® ware, Ubisoftoft MotionBuilder™ grounded ththee software enabled assassin inn his In Assassin’s Creed, th the assassin to 12 centuryy boots Ubisoft used and his run-time-time ® ® fl uidly jump Autodesk 3ds Max environment.nt. software to create from rooftops to a hero character so cobblestone real you can almost streets with ease. feel the coarseness of his tunic. HOW UBISOFT GAVE AN ASSASSIN HIS SOUL. autodesk.com/Games IImmagge cocouru tteesyy of Ubiisofft Autodesk, MotionBuilder, HumanIK and 3ds Max are registered trademarks of Autodesk, Inc., in the USA and/or other countries. All other brand names, product names, or trademarks belong to their respective holders. © 2007 Autodesk, Inc. All rights reserved. []CONTENTS SEPTEMBER 2007 VOLUME 14, NUMBER 8 FEATURES 7 SAVING THE DAY: SAVE SYSTEMS IN GAMES Games are designed by designers, naturally, but they’re not designed for designers. Save systems that intentionally limit the pick up and drop enjoyment of a game unnecessarily mar the player’s experience. This case study of save systems sheds some light on what could be done better. By David Sirlin 13 SABOTEUR: THE WILL TO FIGHT 7 Pandemic’s upcoming title SABOTEUR uses dynamic color changes—from vibrant and full, to black and white film noir—to indicate the state of allied resistance in-game. -

Digital Dystopia: Player Control and Strategic Innovation in the Sims Online

Chapter 12 DIGITAL DYSTOPIA: PLAYER CONTROL AND STRATEGIC INNOVATION IN THE SIMS ONLINE Francis F. Steen, Mari Siˆan Davies, Brendesha Tynes, and Patricia M. Greenfield 1. Introduction Around New Year 2004, a quiet year after the official launch, The Sims Online hit the global headlines. Disappointingly, the topic was not a celebration of how this “new virtual frontier,” this “daring collective social experiment,” had succeeded in bringing “our divided nation” together, as Time magazine had blithely prophesied [1]. Instead, the media reported that the online game had turned into a Biblical den of iniquity, a Sin City, a virtual Gomorrah—and that the whistleblower who bore witness to this had his account terminated [2–5]. Rivaling mafia organizations were practicing extortion and intimidation, pimps running brothels where underage girls provided sex for money, and con artists scamming newbies out of their start capital. Maxis, the company that designed and operated the game, maintained a relaxed laissez-fair policy of light and somewhat haphazard intervention. The first mafias and in-game brothels had been established already in the early days of beta-testing; they continued to operate unchecked. Pretend crime paid well and recruitment was good, leading to a rapidly mutating series of inventive scams targeting the inexperienced and the unwary. It wasn’t meant to be like this. Gordon Walton, one of the chief designers, had spoken in glowing terms of the game’s potential to provide opportunities for better relations between people. While “all of our mass media positions us to believe our neighbors are psychopaths, cheating husbands, and just bad people,” The Sims Online would short circuit our distrustful negative stereotypes [6]. -

In the Archives Here As .PDF File

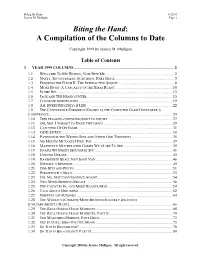

Biting the Hand 6/12/01 Jessica M. Mulligan Page 1 Biting the Hand: A Compilation of the Columns to Date Copyright 1999 by Jessica M. Mulligan Table of Contents 1 YEAR 1999 COLUMNS ...................................................................................................2 1.1 WELCOME TO MY WORLD; NOW BITE ME....................................................................2 1.2 NASTY, INCONVENIENT QUESTIONS, PART DEUX...........................................................5 1.3 PRESSING THE FLESH II: THE INTERACTIVE SEQUEL.......................................................8 1.4 MORE BUGS: A CASUALTY OF THE XMAS RUSH?.........................................................10 1.5 IN THE BIZ..................................................................................................................13 1.6 JACK AND THE BEANCOUNTER....................................................................................15 1.7 COLOR ME BONEHEADED ............................................................................................19 1.8 AH, SWEET MYSTERY OF LIFE ................................................................................22 1.9 THE CONFERENCE FORMERLY KNOWN AS THE COMPUTER GAME DEVELOPER’S CONFERENCE .........................................................................................................................24 1.10 THIS FRAGGED CORPSE BROUGHT TO YOU BY ...........................................................27 1.11 OH, NO! I FORGOT TO HAVE CHILDREN!....................................................................29 -

IGDA Online Games White Paper Full Version

IGDA Online Games White Paper Full Version Presented at the Game Developers Conference 2002 Created by the IGDA Online Games Committee Alex Jarett, President, Broadband Entertainment Group, Chairman Jon Estanislao, Manager, Media & Entertainment Strategy, Accenture, Vice-Chairman FOREWORD With the rising use of the Internet, the commercial success of certain massively multiplayer games (e.g., Asheron’s Call, EverQuest, and Ultima Online), the ubiquitous availability of parlor and arcade games on “free” game sites, the widespread use of matching services for multiplayer games, and the constant positioning by the console makers for future online play, it is apparent that online games are here to stay and there is a long term opportunity for the industry. What is not so obvious is how the independent developer can take advantage of this opportunity. For the two years prior to starting this project, I had the opportunity to host several roundtables at the GDC discussing the opportunities and future of online games. While the excitement was there, it was hard not to notice an obvious trend. It seemed like four out of five independent developers I met were working on the next great “massively multiplayer” game that they hoped to sell to some lucky publisher. I couldn’t help but see the problem with this trend. I knew from talking with folks that these games cost a LOT of money to make, and the reality is that only a few publishers and developers will work on these projects. So where was the opportunity for the rest of the developers? As I spoke to people at the roundtables, it became apparent that there was a void of baseline information in this segment. -

Crowdfunding Your Game Company Via a Title III/Reg CF Raise (Consumer Equity Crowdfunding)

Crowdfunding Your Game Company via a Title III/Reg CF Raise (Consumer Equity Crowdfunding) Gordon Walton President, ArtCraft Entertainment, Inc. What We’ll Cover Today ● Who am I? ● Equity Crowdfunding Overview ● Statistics on Title III Raises ● Preparing your Raise ● Executing your Raise ● Closing your Raise ● Ongoing Shareholder Communication ● Summary ● Q&A Gordon Walton ● First commercial computer game in 1977 (Trek-X for the Pet 2001) ● First indie company 1984-89 building 20 games (Shard of Spring, Gato, Sub Battle Simulator, PT-109, Reader Rabbit, The Playroom, NFL Challenge, Harpoon, more…) ● Went “corporate” in 1989, working for Three-Sixty Pacific, Konami, GameTek, Alliance Interactive, Kesmai, Electronic Arts (Origin and Maxis), Sony Online Entertainment, Electronic Arts (BioWare) ● Currently an “Indie” building the MMO Crowfall® Equity Crowdfunding Overview ● Rewards Crowdfunding .vs. Equity Crowdfunding ● What is a Title III/Reg CF offering? ● How is this different than a Reg D (VC or Angel Investor) offering? ● Working with a portal ● Communication restrictions Statistics on Title III Raises Close day stats ● $669,497 and over 1,200 investors ● 9th largest Title III/Reg CF investment out of ~142 starts and 74 reaching minimum funding ● Our raise was ~3.6% of all Title III money to date ● We raised 70% of all Title III money in our last week of the raise ● We raised more than the other 3 Indiegogo launch titles combined (games are hot!) Preparing Your Raise ● Picking an Attorney ● Picking a Portal to Work With ● Preparing -

December 1998

DECEMBER 1998 GAME DEVELOPER MAGAZINE V GAME PLAN 600 Harrison Street, San Francisco, CA 94107 t: 415.905.2200 f: 415.905.4962 w: www.gdmag.com Ditch the Death March Publisher Cynthia A. Blair cblair@mfi.com EDITORIAL Editor-in-Chief t the conclusion of World As Walton explains in his article, Alex Dunne [email protected] War II, Japan was nowhere Kesmai (like practically every game Managing Editor near the industrial power- development company) experienced Tor D. Berg [email protected] Departments Editor A house that it is today. The intense pressure to complete a number Wesley Hall [email protected] management of Japanese companies of games in time to guarantee their Art Director was almost feudal in nature: plant man- delivery to stores by Christmas. The Laura Pool lpool@mfi.com agers were practically overlords, and burnout and frustration that this used Editor-At-Large Chris Hecker [email protected] workers were viewed as serfs. One of the to cause his teams prompted the com- Contributing Editors people who helped turn Japan around pany to find ways to gain better control Jeff Lander [email protected] in the ‘50s was American management of projects. And while Walton stresses Mel Guymon [email protected] consultant Dr. Edwards Deming. that Kesmai’s developers still encounter Omid Rahmat [email protected] Advisory Board Deming’s lesson to managers in the occasional “crunch period,” adopt- Hal Barwood LucasArts Japan and America was fairly simple. In ing formalized development standards Noah Falstein The Inspiracy a nutshell, he said that managers’ infat- and procedures for their projects has Brian Hook id Software Susan Lee-Merrow Lucas Learning 2 uation with short-term thinking, merit given everyone more confidence in esti- Mark Miller Harmonix systems, quotas, management by objec- mating work duration, resulted in fewer Paul Steed id Software bugs in their games, and made the Dan Teven Teven Consulting tives (MBO), and so on, was all wrong. -

Download 860K

Biting the Hand 6/12/01 Jessica M. Mulligan Page 1 Biting the Hand: A Compilation of the Columns to Date Copyright 2001 by Jessica M. Mulligan Copyright 2000 by Jessica Mulligan. All right reserved. Biting the Hand 6/12/01 Jessica M. Mulligan Page 2 Table of Contents 1 THE 1997 COLUMNS......................................................................................................6 1.1 ISSUE 1: APRIL 1997.....................................................................................................6 1.1.1 ACTIVISION??? WHO DA THUNK IT? .............................................................7 1.1.2 AMERICA ONLINE: WILL YOU BE PAYING MORE FOR GAMES?..................8 1.1.3 LATENCY: NO LONGER AN ISSUE .................................................................12 1.1.4 PORTAL UPDATE: December, 1997.................................................................13 1.2 ISSUE 2: APRIL-JUNE, 1997 ........................................................................................15 1.2.1 SSI: The Little Company That Could..................................................................15 1.2.2 CompuServe: The Big Company That Couldn t..................................................17 1.2.3 And Speaking Of Arrogance ...........................................................................20 1.3 ISSUE 3 ......................................................................................................................23 1.3.1 December, 1997.................................................................................................23 -

Game Developer’S Editors Have Written a Third-Party Postmortem of the Entire Franchise, Trying to Pin Down PAC-MAN’S Continuing Appeal

>> BOOK REVIEW MEL SCRIPTING FOR MAYA ANIMATORS DECEMBER 2005 THE LEADING GAME INDUSTRY MAGAZINE >>TOO HOT FOR YOU >>FUTURE OF FLOW >>GAIJIN ATTACK COMPARING RATINGS ART PIPELINES FOR BUSINESS SMARTS FOR AS GAMES MATURE NEXT-GEN CONSOLES EASTERN PROMISE POSTMORTEM: NAMCO’s PAC-MAN DISPLAY UNTIL JANUARY 16, 2006 Havok games Xbox360 Games Current Gen Games Amped 3 Swat 4 NBA Live 06 Half-Life 2 Condemned: Criminal Origins Halo 2 The Elder Scrolls IV: Oblivion Mercenaries The Outfit Medal of Honor: Pacific Assault Perfect Dark Zero Medal of Honor: European Assault Saint’s Row Max Payne 2 Mortal Kombat: Shaolin Monks and 40+ more next-gen AstroBoy titles in development... Full Spectrum Warrior Brothers in Arms: Road to Hill 30 Brothers in Arms: Earned in Blood Tom Clancy’s Ghost Recon 2 The Matrix: Path of Neo Marvel Nemesis Painkiller FEAR Tom Clancy’s Rainbow 6: Lockdown Darkwatch Destroy All Humans and the list goes on... Supposed Competitor Uhhh . one PC game. Can you even name it? The World’s Best Developers Turn to Havok Stay Ahead of the Game!TM []CONTENTS DECEMBER 2005 VOLUME 12, NUMBER 11 FEATURES 11 RATED AND WILLING As video game violence turns more and more heads as a hot-button issue, it has become clear that the majority of the anti- video game lobby, and indeed a portion of the development community, is under- informed about just how the ratings systems work for games. In this feature, we dissect the ratings systems across four major territories—the U.S., the U.K., Germany, and Australia—to give a better impression of how the ratings board work to keep games in the right hands. -

Table of Contents

The Complete Wargames Handbook By James F. Dunnigan The Complete Wargames Handbook Table of Contents Dedication Acknowledgements Introduction Chapter 1. What is a Wargame 1. Overview 2. Turn 1: U.S. Movement Phase 3. Turn 1: U.S. Combat Phase 4. Turn 1: German Movement and Combat Phase 5. Turn 2: U.S. Movement Phase 6. Turn 2: U.S. Combat Phase 7. Turn 2: German Movement and Combat Phase 8. Conclusion Chapter 2. How to Play Wargames 1. Overview 2. How to Win 3. How to Win with the Losing Side 4. Overcoming Math Anxiety 5. Strategy and Tactics of Play 6. For the Defense 7. The Importance of Quality of Play 8. Wargaming Technique 9. Tempo and Shaping 10. How to Play Without an Opponent 11. Playing by Mail and Team Play 12. How to Get into Gaming Painlessly 13. Playing Computer Wargames 14. The Technical Terms of Wargaming Chapter 3. Why Plan the Game 1. Information 2. History 3. Special Problems of Air and Naval Games Page 1 of 291 ©JF Dunnigan 1997,2005 PDF format may not be recreated without permission from Richard Mataka The Complete Wargames Handbook Chapter 4. Designing Manual Games 1. How to Do It Yourself 2. Designing a Game Step by Step 3. Why the Rules are The Way They Are 4. The Drive on Metz: September 1944 Chapter 5. History of Wargames 1. Overview 2. Hey, Let's Start a Wargame Company in the Basement! 3. The Conventions 4. Into the 80's 5. Analytic History, and What Is a Simulation Anyway? 6. -

Stakeholder Management in Crowdfunded Video Game Development

Fabian Unger Stakeholder management in crowdfunded video game development Faculty of Information Technology and Communication Sciences Master’s Thesis May 2019 2 ABSTRACT Fabian Unger: Stakeholder management in crowdfunded video game development Master’s Thesis, 155 pages, 7 appendices Tampere University Master's Degree Programme in Media Management May 2019 This case study examines, how stakeholder interests affect reward-based crowdfunded video game development, how managers cope with (potential) stakeholder conflicts, and the similarities and differences between crowdfunding video game projects of different scales. As research on stakeholder interests in the production of crowdfunded video games is scarce, this study thus aims to fill a gap in scholarly literature. The purpose of this study is to contribute to the field of managing crowdfunding projects using a reward-based model, to examine stakeholder-developer interactions and the management of interests in crowdfunded video games, specifically from a manager’s point of view. The outcomes of this study should provide valuable insights for media managers, who deal with varying stakeholders as part of the development of a crowdfunded video game. The study examines seven cases of crowdfunded video games developed by video game companies using a reward-based financing model. It takes a qualitative approach, using semi-structured in-depth interviews with a sample of one employee per company in charge of the overall game development process. The results demonstrate the various ways in which stakeholders influence the development process, similarities and differences of crowdfunding projects of various size, and the impact of crowdfunding on the video game development process in general. -

The History of Virtual Worlds

Bartle, Richard A.: From MUDs to MMORPGs: The History of Virtual Worlds. In Hunsinger, Jeremy; Klastrup, Lisbeth; Allen, Matthew (eds.): International Handbook of Internet Research. Springer, 2010. From MUDs to MMORPGs: The History of Virtual Worlds Dr Richard A. Bartle School of. Computer Science and Electronic Engineering University of Essex, UK Abstract Today's massively multiplayer online role-playing games are the direct descendants of the textual worlds of the 1980s, not only in design and implementation terms, but also in the way they are evolving thematically. Thus far, they have faithfully mirrored the path taken by their forebears. If they continue to do so, what can we expect of the graphical worlds of the future? Introduction Golf was invented in China (Ling, 1991). There is evidence from the Dongxuan Records (Wei, Song dynasty) that a game called chuiwan (“hitting ball”) was played as early as the year 945. A silk scroll, The Autumn Banquet (unknown, Ming dynasty), depicts a man swinging something with the appearance of a golf club at something with the appearance of a golf ball, having the apparent aim of conveying it into something with the appearance of a golf hole. Golf was also invented in France (Flannery and Leech, 2003), where it was known as palle mail. Tax records from 1292 show that makers of clubs and balls had to pay a toll to sell their goods to nobles outside Paris. A book of prayers, Les Heures de la Duchesse de Bourgogne (unknown, c1500), contains illustrations of men swinging something with the appearance of a golf club at something with the appearance of a golf ball, having the apparent aim of conveying it into something with the appearance of a golf hole.