Conceived in Liberty: Volume III: Advance to Revolution

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Samuel Adams

Monumental Milestones Milestones Monumental The Life and of Times samuel adams samuel adams Karen Bush Gibson The Life and Times of samuel Movement Rights Civil The adams Karen Bush Gibson As America’s first politician, Samuel Adams dedicated his life to improving the lives of the colonists. At a young age, he began talking and listening to people to find out what issues mattered the most. Adams proposed new ideas, first in his own newspaper, then in other newspapers throughout the colonies. When Britain began taxing the colonies, Adams encouraged boy- cotting and peaceful protests. He was an organizer of the Boston Tea Party, one of the main events leading up to the American Revolution. The British seemed intent on imprisoning Adams to keep him from speaking out, but he refused to stop. He was one of the first people to publicly declare that the colonies should be independent, and he worked tirelessly to see that they gained that independence. According to Thomas Jefferson, Samuel Adams was the Father of the Revolution. ISBN 1-58415-440-3 90000 9 PUBLISHERS 781584 154402 samueladamscover.indd 1 5/3/06 12:51:01 PM Copyright © 2007 by Mitchell Lane Publishers, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced without written permission from the publisher. Printed and bound in the United States of America. Printing 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Gibson, Karen Bush. The life and times of Samuel Adams/Karen Bush Gibson. p. cm. — (Profiles in American history) Includes bibliographical references and index. -

Chapter 3 America in the British Empire

CHAPTER 3 AMERICA IN THE BRITISH EMPIRE The American Nation: A History of the United States, 13th edition Carnes/Garraty Pearson Education, Inc., publishing as Longman © 2008 THE BRITISH COLONIAL SYSTEM n Colonies had great deal of freedom after initial settlement due to n British political inefficiency n Distance n External affairs were controlled entirely by London but, in practice, the initiative in local matters was generally yielded to the colonies n Reserved right to veto actions deemed contrary to national interest n By 18 th Century, colonial governors (except Connecticut and Rhode Island) were appointed by either the king or proprietors Pearson Education, Inc., publishing as Longman © 2008 THE BRITISH COLONIAL SYSTEM n Governors n executed local laws n appointed many minor officials n summoned and dismissed the colonial assemblies n proposed legislation to them n had power to veto colonial laws n They were also financially dependent on their “subjects” Pearson Education, Inc., publishing as Longman © 2008 THE BRITISH COLONIAL SYSTEM n Each colony had a legislature of two houses (except Pennsylvania which only had one) n Lower House: chosen by qualified voters, had general legislative powers, including control of purse n Upper House: appointed by king (except Massachusetts where elected by General Court) and served as advisors to the governor n Judges were appointed by king n Both judges and councilors were normally selected from leaders of community n System tended to strengthen the influence of entrenched colonials n Legislators -

The Earl of Dartmouth As American Secretary 1773-1775

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1968 To Save an Empire: The Earl of Dartmouth as American Secretary 1773-1775 Nancy Briska anderson College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the European History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation anderson, Nancy Briska, "To Save an Empire: The Earl of Dartmouth as American Secretary 1773-1775" (1968). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539624654. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-tm56-qc52 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TO SAVE AH EMPIRE: jTHE EARL OP DARTMOUTH "i'i AS AMERICAN SECRETARY 1773 - 1775 A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of History The College of William and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts By Nancy Brieha Anderson June* 1968 APPROVAL SHEET This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Nancy Briska Anderson Author Approved, July, 1968: Ira Gruber, Ph.D. n E. Selby', Ph.D. of, B Harold L. Fowler, Ph.D. TO SAVE AN EMFIREs THE EARL OF DARTMOUTH AS AMERICAN SECRETARY X773 - 1775 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I first wish to express my appreciation to the Society of the Cincinnati for the fellowship which helped to make my year at the. -

A New Nation Struggles to Find Its Footing: Power Struggles, 1789-1804

Laws/Acts and events by the British Parliament which stress the colonies Emerging themes from this era . Navigation Act of 1660 requires exclusive use of English ships for trade in ➢ Colonial autonomy v. Crown-sanctioned oversight the English colonies and limits exports of tobacco and sugar and other ➢ To what extent should one attempt to regulate or dominate the other? commodities to England or its colonies. ➢ Two economic tensions emerged, both of which were stimulated by the ➢ This is the first of a series of Acts which were designed to direct most progression of the Acts: American trade to England; this is how the Crown strove to encourage ➢ Supply/demand economics practices which supported Mercantilism! ➢ Protectionism of English goods Navigation Act of 1673 (aka ‘Act for the Encouragement of Trade’) set up ➢ Territorial issues (as an extension of big powers rivalry) the office of customs commissioner in the colonies to collect duties/taxes on ➢ Competing territorial claims (British, French, Spanish, Dutch, goods which pass between colonial plantations. Native Americans, etc) which manifested themselves in conflict. 1681, Edmond Andros (Governor of province of NY and the Jersey’s since ➢ The idea begins to emerge in England that the colonies were not doing 1674) charged with dishonesty and favoritism in the collection of revenues. their share to help the mother country materialistically, nor to protect Circa.1686, King James II of England begins consolidating the colonies of it economically; in other words, the colonies were starting to be a New England into a single dominion, depriving the colonists of their local financial drain on England. -

PUB DUE Three At,Ated Reading Guides Were Aeveloped

411.. X %. itomesTit1180111 RD 181 929 IS 000 043 AUTHOR Schneider, Eric C.: And Others .TITLE Boston:1411 Orban Community. Boston and the American - RevcilutiOn: The Leaders, the*Issue!and the Common Man. Boston's Architecture: From First Tawnhouseto New City Hall. Boston's Artisans of the Eighteenth Century. Annotated Reading Lists. INSTITUTION Bos.ton Public Library, Hass. SPONS AGENCY National Endowment for the_Humanities(NFAH),' Washington, O.C PUB DUE 77 NOTE Fo'irelated documentso'see IRJ 008 042-046 EDRS PRICE HF01/PC03 Plus Postage: ,DESCRIPTORS Annotated BibliographAes: 4gArchitecture:*Craftsmen; Educational Programs: HumanitiesInstruction: *Local History: Public' Librarikts: Resource Guidesi Apevoldtionar.War (Onited.statefl ABSTRA.CT The three at,ated reading guideswere Aeveloped for courses offeced At the Bos_n Public,Library under the,National Endowments,for the'Human ).ties Library LearningProgram. The first lists-42 selectedrece t works of major importance covering theareas of colonial society, political structure,and the Aterican .Revolutivon.piel27 titles cited in thesecoud include not only books about Bostoearehitectureet but books aboutBoston which deal With '7 various of the city's buildings: guidebooksto 'individual buildings have been excluded. The 31 readingson Boston's artisans and their products are (II:Added into three sections:(1) the topography of th city from 1726 to 1815:(2) the artisan coamunfty and thesoc structure of'Boston, focusingon the-role'of craftsmen i Revolution and their cheinging social status:and,(3) e crafts of 18th century.Boston anA some biographical materialsot individuai 'artisans. (RAA) 4 f ****-*************************************************.*********4******** 1;4 Reproluctions suppli44 by raps are the beet thatcan be eaCle frou.the original docuaellt. -

The American Revolution Presentation

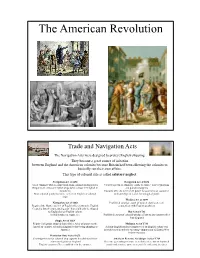

The American Revolution Trade and Navigation Acts The Navigation Acts were designed to protect English shipping. ! They became a great source of irritation between England and the American colonies because Britain had been allowing the colonies to basically run their own affairs. ! This type of colonial rule is called salutary neglect. Navigation Act of 1651 Navigation Act of 1696 Goal: eliminate Dutch competition from colonial trading routes Created system of admiralty courts to enforce trade regulations Required all crews on English ships to be at least 1/2 English in and punish smugglers nationality Customs officials were given power to issue writs of assistance Most colonial goods had to be carried on English or colonial to board ships to search for smuggled goods ships ! ! Woolens Act of 1699 Navigation Act of 1660 Prohibited colonial export of woolen cloth to prevent Required the Master and 3/4 of English ship crews to be English competition with English producers Created a list of "enumerated goods” that could only be shipped ! to England or an English colony Hat Act of 1732 included tobacco, sugar, rice Prohibited export of colonial-produced hats to any country other ! than England Staple Act of 1663 ! Required all goods shipped from Africa, Asia, or Europe to the Molasses Act of 1733 American colonies to land in England before being shipping to All non-English molasses imported to an English colony was America heavily taxed in order to encourage importation of British West ! Indian molasses Plantation Duty Act of 1673 ! Created -

Liberty, Property and Rationality

Liberty, Property and Rationality Concept of Freedom in Murray Rothbard’s Anarcho-capitalism Master’s Thesis Hannu Hästbacka 13.11.2018 University of Helsinki Faculty of Arts General History Tiedekunta/Osasto – Fakultet/Sektion – Faculty Laitos – Institution – Department Humanistinen tiedekunta Filosofian, historian, kulttuurin ja taiteiden tutkimuksen laitos Tekijä – Författare – Author Hannu Hästbacka Työn nimi – Arbetets titel – Title Liberty, Property and Rationality. Concept of Freedom in Murray Rothbard’s Anarcho-capitalism Oppiaine – Läroämne – Subject Yleinen historia Työn laji – Arbetets art – Level Aika – Datum – Month and Sivumäärä– Sidoantal – Number of pages Pro gradu -tutkielma year 100 13.11.2018 Tiivistelmä – Referat – Abstract Murray Rothbard (1926–1995) on yksi keskeisimmistä modernin libertarismin taustalla olevista ajattelijoista. Rothbard pitää yksilöllistä vapautta keskeisimpänä periaatteenaan, ja yhdistää filosofiassaan klassisen liberalismin perinnettä itävaltalaiseen taloustieteeseen, teleologiseen luonnonoikeusajatteluun sekä individualistiseen anarkismiin. Hänen tavoitteenaan on kehittää puhtaaseen järkeen pohjautuva oikeusoppi, jonka pohjalta voidaan perustaa vapaiden markkinoiden ihanneyhteiskunta. Valtiota ei täten Rothbardin ihanneyhteiskunnassa ole, vaan vastuu yksilöllisten luonnonoikeuksien toteutumisesta on kokonaan yksilöllä itsellään. Tutkin työssäni vapauden käsitettä Rothbardin anarko-kapitalistisessa filosofiassa. Selvitän ja analysoin Rothbardin ajattelun keskeisimpiä elementtejä niiden filosofisissa, -

Ballads and Poems Relating to the Burgoyne Campaign. Annotated

: : : to vieit Europe, I desire to state that his great accjuaintancc witti military matters, his long and faithful research into the military histories of modern nations, his correct comprehension of our own late war, and his intimacy with man.v of our leading Generals and Statesmen durinjr the period of its con- tinuance, with his tried and devoted loyalty and patriotism, recommend him as an eminently suitable person to visit foreign countries, to impart as weU as receive proper views upon all such subjects as are connected with his position as a military writer. Such high qualifications, apart from his being a gentleman of family, of fortune, and of refined cultivation, are entitled to the most favorable consideration from all thosH who esteem and admire them. With great respect, A. PLEA8ANTON, Bvt. Major- Gen'l, U.S.A. ExEcunvK Manbioh, I; Wati., D. C, July 13, 1869. f I heartily concur with Gen'l Pleasanton in his high appreciation of the services rendered by Gen'l de Peysteb, upon whom the State of New York has conferred the rank of Brevet Major-General. I commend him to the favorable consideration of those whom he may meet in his present visit to Europe. U. S. GRANT. ExEcunri Mansion, 1 W<ukingtm, D. a, July I3th, 1869. Dear Sir • ) I take pleasure in forwarding to you the enclosed endorsement of the President. Yours Very Truly, Gen. J. Watts db Pktsteb. HORACE PORTER.* •Major of Ordnance, V. 8. A. ; Brtvtt Brigadier-General V. S. A.; A.-de-C. to tke General-in-Chief ; and Private Secretary to the Pretident of the U.S. -

The Life and Times of Henry Rutgers—Part One: 1636–1776

42 THE JOURNAL OF THE RUTGERS UNIVERSITY LIBRARIES BENEVOLENT PATRIOT: THE LIFE AND TIMES OF HENRY RUTGERS—PART ONE: 1636–1776 BY DAVID J. FOWLER [email protected] From the steeple of the New Dutch Church on Nassau Street in New York, mid-18th-century viewers saw “a most beautiful prospect, both of the city beneath and the surrounding country.” Looking eastward, they would have seen a number of hills. One, about 80 feet in height, was at Corlear’s Hook, a distinctive feature of lower Manhattan Island that jutted into the East River. West of that point along the riverfront and extending inland was the choice, 100- acre parcel known as “the Rutgers Farm.” Situated in the Bowery Division of the city’s Out Ward, it was a sprawling tract that for decades maintained a rural character of hills, fields, gardens, woods, and marshes. In 1776, the young American officer and budding artist John Trumbull commented on the “beautiful high ground” that surrounded the Rutgers property.1 In New York City, one was never very far from the water. Commerce—with Europe, the West Indies, and other colonies— drove the town’s economy. It was a gateway port that was also an entrepôt for the transshipment of goods into the adjoining hinterland. Merchants and sea captains garnered some profits illegally via “the Dutch trade” (i.e., smuggling) or, in contravention of customs regulations, via illicit trade with the enemy during wartime. Since the Rutgers Farm fronted on the East River, where the major port facilities were located, it was strategically situated to capitalize on maritime pursuits. -

The Cradle of the American Revolution

The Cradle Of The American Revolution by The Alexandria Scottish Rite PREFACE: This research report is unique, in that the presentation is in dramatic form, rather than the usual reading of a paper. The facts are as we know them today. However, the Scottish Rite has taken a little "creative freedom" in its manner of presenting those facts. It is the hope that this will be both informative and interesting to the members of the A. Douglas Smith Jr. Lodge of Research #1949. Cast: Cradle of the American Revolution Worshipful Master — Harry Fadley Visitor #2: — James (Pete) Melvin Secretary: — William Gibbs Visitor #3: — Victor Sinclair Paul Revere: — James Petty Tyler: — Ray Burnell Visitor #1: — John McIntyre Stage: — Drew Apperson INTRODUCTION: have come up with only guess work, I figure the best way to find an answer to Narrator: LIBERTY! A PEARL OF GREAT this question is to be there and see what PRICE! Every one wants it! Only a few goes on at the time! Let’s go back in have it! Those who have it are apt to lose time to the "Cradle of The American it! The price of liberty is high! Not in Revolution" where it all began. The monetary figures, but in human lives! Cradle of The American Revolution was Thousands upon thousands of human a title given by historians to the Green lives! Dragon Tavern, a large brick building standing on Union Street in Boston, Today we are witnessing the difficult Mass. It was built in the end of the struggle for liberty all over the world; seventeenth or the beginning of the the middle East, Africa, Eastern Europe eighteenth century. -

The Navigation Acts and Colonial Massachusetts Industry

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Master's Theses Theses and Dissertations 1955 The aN vigation Acts and Colonial Massachusetts Industry William O. Madden Loyola University Chicago Recommended Citation Madden, William O., "The aN vigation Acts and Colonial Massachusetts ndusI try" (1955). Master's Theses. Paper 1137. http://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_theses/1137 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 1955 William O. Madden THE NAVIGATION ACTS AND COLONIAL MASSACHUSETTS INDUSTRr bl William O. Madden, S.J. A Th•• ie Submitted to the Facultl of the Graduate School of LOlo1a Unlveraltl in Partial Fulfl1laent of the Requirements for the Degree of Malter of Arts Januarr 19S5 LIP'.B Wllllam O. Madden, a.J., waa born at Chicago" Illlnols" Maroh 11, 1926. He was graduated trom Ouaplon Hlgb. Sohool, Pralrle du Chien, Wisconsln, In Mal' ~ 1944. In JUDe of' the same 7eal' he entered the lovltlate ot the Sacred Heart, Mlltord, Ohio, an attlliate ot Xavier Unlversltl'. In th. summer ot 1948 he was tran.terred to We.t Baden College, We.t Baden Springs, Indiana, an attil!ate ot L0l'ola Univers!tl', where he pursued cour.e. in philo.oph, and hiator;y. He received his degree ot Bachelor of' Art. In Latin 1n Februar;y, 1949. -

James Perry and the Morning Chronicle 179O—I821

I JAMES PERRY AND THE MORNING CHRONICLE- 179O—I821 By l yon Asquith Thesis submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the University of London 1973 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract 3 Preface 5 1. 1790-1794 6 2. 1795-1 805 75 3. 1806-1812 (i) ThB Ministry of the Talents 184 (ii) Reform, Radicalism and the War 1808-12 210 (iii) The Whigs arid the Morning Chronicle 269 4. Perry's Advertising Policy 314 Appendix A: Costs of Production 363 Appendix B: Advertising Profits 365 Appendix C: Government Advertisements 367 5. 1813-1821 368 Conclusion 459 Bibliography 467 3 A BSTRACT This thesis is a study of the career of James Perry, editor and proprietor of the Morning Chronicle, from 1790-1821. Based on an examination of the correspondence of whig and radical polit- icians, and of the files of the morning Chronicle, it illustrates the impact which Perry made on the world of politics and journalism. The main questions discussed are how Perry responded, as a Foxite journalist, to the chief political issues of the day; the extent to which the whigs attempted to influence his editorial policy and the degree to which he reconciled his independence with obedience to their wishes4 the difficulties he encountered as the spokesman of an often divided party; his considerable involvement, which was remarkable for a journalist, in party activity and in the social life of whig politicians; and his success as a newspaper proprietor concerned not only with political propaganda, but with conducting a paper which was distinguished for the quality of its miscellaneous features and for its profitability as a business enterprise.