Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Anglo-Norman Views on Frederick Barbarossa and The

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Edinburgh Research Explorer Edinburgh Research Explorer English views on Lombard city communes and their conflicts with Emperor Frederick I Barbarossa Citation for published version: Raccagni, G 2014, 'English views on Lombard city communes and their conflicts with Emperor Frederick I Barbarossa' Quaderni Storici, vol. 145, pp. 183-218. DOI: 10.1408/76676 Digital Object Identifier (DOI): 10.1408/76676 Link: Link to publication record in Edinburgh Research Explorer Document Version: Peer reviewed version Published In: Quaderni Storici Publisher Rights Statement: © Raccagni, G. (2014). English views on Lombard city communes and their conflicts with Emperor Frederick I Barbarossa. Quaderni Storici, 145, 183-218. 10.1408/76676 General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Edinburgh Research Explorer is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The University of Edinburgh has made every reasonable effort to ensure that Edinburgh Research Explorer content complies with UK legislation. If you believe that the public display of this file breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 05. Apr. 2019 English views on Lombard city communes and their conflicts with Emperor Frederick Barbarossa* [A head]Introduction In the preface to his edition of the chronicle of Roger of Howden, William Stubbs briefly noted how well English chronicles covered the conflicts between Emperor Frederick Barbarossa and the Lombard cities.1 Unfortunately, neither Stubbs nor his * I wish to thank Bill Aird, Anne Duggan, Judith Green, Elisabeth Van Houts and the referees of Quaderni Storici for their suggestions and comments on earlier drafts of this work. -

The Development of Marian Doctrine As

INTERNATIONAL MARIAN RESEARCH INSTITUTE UNIVERSITY OF DAYTON, OHIO in affiliation with the PONTIFICAL THEOLOGICAL FACULTY MARIANUM ROME, ITALY By: Elizabeth Marie Farley The Development of Marian Doctrine as Reflected in the Commentaries on the Wedding at Cana (John 2:1-5) by the Latin Fathers and Pastoral Theologians of the Church From the Fourth to the Seventeenth Century A Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctorate in Sacred Theology with specialization in Marian Studies Director: Rev. Bertrand Buby, S.M. Marian Library/International Marian Research Institute University of Dayton 300 College Park Dayton, OH 45469-1390 2013 i Copyright © 2013 by Elizabeth M. Farley All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America Nihil obstat: François Rossier, S.M., STD Vidimus et approbamus: Bertrand A. Buby S.M., STD – Director François Rossier, S.M., STD – Examinator Johann G. Roten S.M., PhD, STD – Examinator Thomas A. Thompson S.M., PhD – Examinator Elio M. Peretto, O.S.M. – Revisor Aristide M. Serra, O.S.M. – Revisor Daytonesis (USA), ex aedibus International Marian Research Institute, et Romae, ex aedibus Pontificiae Facultatis Theologicae Marianum, die 22 Augusti 2013. ii Dedication This Dissertation is Dedicated to: Father Bertrand Buby, S.M., The Faculty and Staff at The International Marian Research Institute, Father Jerome Young, O.S.B., Father Rory Pitstick, Joseph Sprug, Jerome Farley, my beloved husband, and All my family and friends iii Table of Contents Prėcis.................................................................................. xvii Guidelines........................................................................... xxiii Abbreviations...................................................................... xxv Chapter One: Purpose, Scope, Structure and Method 1.1 Introduction...................................................... 1 1.2 Purpose............................................................ -

The Beguine Option: a Persistent Past and a Promising Future of Christian Monasticism

religions Article The Beguine Option: A Persistent Past and a Promising Future of Christian Monasticism Evan B. Howard Department of Ministry, Fuller Theological Seminary 62421 Rabbit Trail, Montrose, CO 81403, USA; [email protected] Received: 1 June 2019; Accepted: 3 August 2019; Published: 21 August 2019 Abstract: Since Herbert Grundmann’s 1935 Religious Movements in the Middle Ages, interest in the Beguines has grown significantly. Yet we have struggled whether to call Beguines “religious” or not. My conviction is that the Beguines are one manifestation of an impulse found throughout Christian history to live a form of life that resembles Christian monasticism without founding institutions of religious life. It is this range of less institutional yet seriously committed forms of life that I am here calling the “Beguine Option.” In my essay, I will sketch this “Beguine Option” in its varied expressions through Christian history. Having presented something of the persistent past of the Beguine Option, I will then present an introduction to forms of life exhibited in many of the expressions of what some have called “new monasticism” today, highlighting the similarities between movements in the past and new monastic movements in the present. Finally, I will suggest that the Christian Church would do well to foster the development of such communities in the future as I believe these forms of life hold much promise for manifesting and advancing the kingdom of God in our midst in a postmodern world. Keywords: monasticism; Beguine; spiritual formation; intentional community; spirituality; religious life 1. Introduction What might the future of monasticism look like? I start with three examples: two from the present and one from the past. -

Waldensians and Franciscans a Comparative Study of Two Reform Movements in the Late Twelfth and Early Thirteenth Centuries

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Master's Theses Graduate College 8-1971 Waldensians and Franciscans a Comparative Study of Two Reform Movements in the Late Twelfth and Early Thirteenth Centuries Stanley D. Pikaart Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses Part of the Medieval Studies Commons Recommended Citation Pikaart, Stanley D., "Waldensians and Franciscans a Comparative Study of Two Reform Movements in the Late Twelfth and Early Thirteenth Centuries" (1971). Master's Theses. 2906. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses/2906 This Masters Thesis-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WALDENSIANS AND FRANCISCANS A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF TWO REFORM MOVEMENTS IN THE LATE TWELFTH AND EARLY THIRTEENTH CENTURIES by Stanley D, Pikaart A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College in partial fulfillment of the Degree of Master of Arts Western Michigan University Kalamazoo, Michigan August, 1971 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My thanks and appreciations are extended to profes sors Otto Grundler of the Religion department and George H. Demetrakopoulos of the Medieval Institute for their time spent in reading this paper. I appreciate also the help and interest of Mrs. Dugan of the Medieval Institute. I cannot express enough my thanks to Professor John Sommer- feldt for his never-ending confidence and optimism over the past several years and for his advice and time spent going over in detail the several drafts of this paper. -

Timeline1800 18001600

TIMELINE1800 18001600 Date York Date Britain Date Rest of World 8000BCE Sharpened stone heads used as axes, spears and arrows. 7000BCE Walls in Jericho built. 6100BCE North Atlantic Ocean – Tsunami. 6000BCE Dry farming developed in Mesopotamian hills. - 4000BCE Tigris-Euphrates planes colonized. - 3000BCE Farming communities spread from south-east to northwest Europe. 5000BCE 4000BCE 3900BCE 3800BCE 3760BCE Dynastic conflicts in Upper and Lower Egypt. The first metal tools commonly used in agriculture (rakes, digging blades and ploughs) used as weapons by slaves and peasant ‘infantry’ – first mass usage of expendable foot soldiers. 3700BCE 3600BCE © PastSearch2012 - T i m e l i n e Page 1 Date York Date Britain Date Rest of World 3500BCE King Menes the Fighter is victorious in Nile conflicts, establishes ruling dynasties. Blast furnace used for smelting bronze used in Bohemia. Sumerian civilization developed in south-east of Tigris-Euphrates river area, Akkadian civilization developed in north-west area – continual warfare. 3400BCE 3300BCE 3200BCE 3100BCE 3000BCE Bronze Age begins in Greece and China. Egyptian military civilization developed. Composite re-curved bows being used. In Mesopotamia, helmets made of copper-arsenic bronze with padded linings. Gilgamesh, king of Uruk, first to use iron for weapons. Sage Kings in China refine use of bamboo weaponry. 2900BCE 2800BCE Sumer city-states unite for first time. 2700BCE Palestine invaded and occupied by Egyptian infantry and cavalry after Palestinian attacks on trade caravans in Sinai. 2600BCE 2500BCE Harrapan civilization developed in Indian valley. Copper, used for mace heads, found in Mesopotamia, Syria, Palestine and Egypt. Sumerians make helmets, spearheads and axe blades from bronze. -

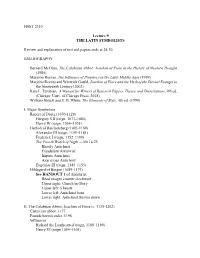

HSST 2310 Lecture 9 the LATIN SYMBOLISTS Review And

HSST 2310 Lecture 9 THE LATIN SYMBOLISTS Review and explanation of test and papers ends at 24:30 BIBLIOGRAPHY Bernard McGinn, The Calabrian Abbot: Joachim of Fiore in the History of Western Thought (1985) Marjorie Reeves, The Influence of Prophecy in the Later Middle Ages (1969) Marjorie Reeves and Warwick Gould, Joachim of Fiore and the Myth of the Eternal Evangel in the Nineteenth Century (2002) Kate L. Turabian, A Manual for Writers of Research Papers, Theses, and Dissertations, 9th ed. (Chicago: Univ. of Chicago Press, 2018) William Struck and E. B. White, The Elements of Style, 4th ed. (1999) I. Major Symbolists Rupert of Deutz (1070-1129) Gregory VII (reign, 1073–1085) Henry IV (reign, 1054–1105) Gerhoh of Reichersberg (1093-1169) Alexander III (reign, 1159–1181) Frederick I (reign, 1152–1190) The Fourth Watch of Night —Mt 14:25 Bloody Antichrist Fraudulent Antichrist Impure Antichrist Avaricious Antichrist Eugenius III (reign, 1145–1153) Hildegard of Bingen (1089-1179) See HANDOUT 1 of Antichrist Read images counter clockwise Upper right: Church in Glory Upper left: 5 beasts Lower left: Antichrist born Lower right: Antichrist thrown down II. The Calabrian Abbot: Joachim of Fiore (c. 1135-1202) Cistercian abbot, 1177. Founds hermit order, 1196 Influences Richard the Lionhearted (reign, 1189–1199) Henry VI (reign 1054–1105) 2 Pope Lucius III (reign, 1181–1185) Innocent III (reign, 1198–1216) Works Ten Stringed Psalter Concord of Old and New Testaments Exposition of the Apocalypse Book of Figures Influence: see Reeves in bibliography III. Joachim’s System Liber Figurarum (“Book of Figures”) See HANDOUT 2 of Liber IV. -

Papal Bulls Set the Stage for Domination and Slavery a Papal Bull Is a Type of Public Decree, Letters Patent, Or Charter Issued by a Pope of the Catholic Church

SANCTIONS AGAINST ETHNIC POPULATIONS Papal Bulls set the stage for Domination and Slavery A papal bull is a type of public decree, letters patent, or charter issued by a pope of the Catholic Church. Bull from Bulla / Seal Sanctioned by the Pope(s) who wrote one - Papal Bull (Decree) - after another that gave instruction and latitude to ferret out heresy. Local and regional church officials were empowered to question, punish, imprison, convert, enslave, torture and kill in the name of the Catholic Church giving rise to ‘sanctioned violence against ‘the other’ 1184 - November 4 - Pope Lucius III Ad Abolendam - Established the Inquisition To abolish the malignity of diverse heresies,…. it is but fitting that the power committed to the Church should be awakened, …. of the imperial strength, 13 C Bulla seal that by the concurring assistance ……both the insolence and impertinence of the heretics, in their false designs, may be crushed,…. 1452 June 18- Pope Nicholas V Dum Diversas It authorized Alfonso V of Portugal to reduce any “Saracens (Muslims) and pagans and any other unbelievers” to perpetual slavery. This facilitated the Portuguese slave trade from West Africa. 1455 - January 5 - Pope Nicholas V Romanus Pontifex Extended to The Kingdom of Portugal, Alfonso V and his son, the Catholic nations of Europe dominion over discovered lands during the Age of Discovery. Along with sanctifying the seizure of non-Christian lands, it allowed for the enslavement of native, non-Christian peoples in Africa and the New World. 1478- November 1 -Pope Sixtus IV. Exigit Sincerae Devotionis Affectus Authorized King Ferdinand V of Aragon and Queen Isabella I of Castile to establish their own Inquisition as well as appoint inquisitors without interference from the Church. -

SOME IMPORTANT DATES 1170 Birth of Saint Dominic in Calaruega, Spain. 1203 Dominic Goes with His Bishop, Diego, on a Mission To

SOME IMPORTANT DATES 1170 Birth of Saint Dominic in Calaruega, Spain. 1203 Dominic goes with his bishop, Diego, on a mission to northern Europe. On the way he discovers, in southern France, people who no longer accept the Christian faith. 1206 Foundation of the first monastery of Dominican nuns in Prouille, France. 1215 Dominic and his first companions gather together in Toulouse. 1216 Pope Honorius III approves the foundation of the Dominican Order. 1217 Dominic disperses his friars to set up communities in Paris, Bologna, Rome and Madrid. 1221 8th August, Dominic dies in Bologna. 1285 Foundation of the Dominican Third Order. Its Rule approved by the Master General, Munoz de Zamora. 1347 Birth of Catherine of Siena, patroness of Lay Dominicans. 1380 29th April, Catherine of Siena dies in Rome. 1405 Pope Innocent VII approves Rule of the Third Order. 1898 Establishment of the Dominican Order in Australia. 1932 Second Rule of the Third Order approved by the Master General, Louis Theissling. 1950 Establishment of the Province of the Assumption. 1964 Third Rule approved. 1967 First National Convention of Dominican Laity in Australia (held in Canberra). 1969 Fourth Rule promulgated by the Master General, Aniceto Fernandez. 1972 Fourth Rule approved (on an experimental basis) by the Sacred Congregation for Religious). 1974 Abolition of terms "Third Order" and "Tertiaries". 1985 First International Lay Dominican Congress held in Montreal, Canada. 1987 Fifth (present) Rule approved by the Sacred Congregation for Religious and Secular Institutes and promulgated by the Master, Damien Byrne. The Dominican Laity Handbook (1994) P68 THE THIRD ORDER OF ST. -

The Third Order of Saint Dominic

THE THIRD ORDER OF SAINT DOMINIC RAYMOND ALGER, O.P. LITTLE more than a decade ago the then reigning Holy Father, Pope Benedict XV, spoke thus of the Third Order of St. Dominic: "In the midst of the great dangers which on all sides threaten the faith and morals of the Christian people, it is Our duty to safeguard the faithful by pointing out to them those means of holiness which seem to Us the most useful and opportune for their defense and for their progress. Amongst those means We recognize the Dominican Third Order as one of the most eminent, most easy and most sure. Knowing the snares of the world and, not less, the salutary remedies flowing from the Divine teach ing of the Gospel, the glorious Patrician Dominic was inspired to found it, so that in this association every class of persons might, as it were, find a realization of the desire for a more perfect life." In these words Pope Benedict summed up the entire activity of the Third Order. How well the Third Order of St. Dominic is suited to take a leading role in present day Catholic Action may be seen from the very origin and development of this important branch of the Dominican family and also from the fruits of its labors which have added lustre to the light of the Church for over seven centuries. In speaking of the Third Order we refer to it primarily as an association of the laity, for as such was it first founded. Many diffi culties beset the path of the student who would attempt to trace the history of the Third Order from one original source and this because of the fact that St. -

Table of Contents Provided by Blackwell's Book Services and R.R

Introduction Heresy And Authority In Medieval Europe p. 1 Bibliography of Sources in Translation p. 10 p. 13 p. 30 St. Augustine: on Manichaeism p. 32 Theodoret: The Rise of Arianism p. 39 Theodoret: Arius's Letter to Eusebius of Nicomedia p. 41 The Creed of Nicaea (325) and Constantinople (381) p. 42 Compelle Intrare. the Coercion of Heretics in the Theodosian Code, 438 p. 43 St. Isidore of Seville: On the Church and the Sects p. 48 Alcuin: Against the Adoptionist Heresy of Felix p. 51 p. 57 Paul of St. Père De Chartres: Heretics at Orléans, 1022 p. 66 p. 72 p. 75 p. 79 p. 81 St. Bernard to Pope Innocent II: Against Abelard, 1140 p. 88 p. 91 p. 95 p. 103 The Sermon of Cosmas the Priest Against Bogomilism p. 109 p. 118 The Cathar Council at Saint-Félix-De-Caraman, 1167 p. 122 Pierre Des Vaux De Cernay: The Historia Albigensis p. 124 Rainier Sacconi: A Thirteenth-Century Inquisitor on Catharism p. 126 p. 133 p. 139 p. 144 p. 145 p. 147 p. 150 p. 151 p. 165 The Third Lateran Council, 1179: Heretics Are Anathema p. 169 Pope Lucius III: The Decretal Ad Abolendum, 1184 p. 171 The Fourth Lateran Council, 1215: Credo and Confession, Canons 1, 3, 21 p. 174 Pope Innocent III: The Decretal Cum Ex Officii Nostri, 1207 p. 178 Burchard of Ursperg: On the New Orders p. 179 St. Antony's Sermon to the Fish p. 181 p. 182 p. 184 p. 189 Caesarius of Heisterbach: The Stake p. -

The Fourth Lateran Ordo of Inquisition Adapted to the Prosecution of Heresy

Chapter 3 The Fourth Lateran Ordo of Inquisition Adapted to the Prosecution of Heresy Henry Ansgar Kelly 1 Prosecuting Heresy before Inquisition It used to be common to refer to the whole sweep of Church prosecution of heresy from the Middle Ages through the Early Modern Period as “the Inquisition,” a usage that is yet to be seen in the recent Dizionario storico dell’Inquisizione (Historical Dictionary of the Inquisition).1 There is still a wide- spread assumption that “inquisition” as a form of trial was developed for pros- ecuting heresy and was synonymous with the fight against heresy. As we will see, this was not so, in the form in which it was introduced and explained at the Fourth Lateran Council in 1215. It was only later adopted and adapted for the fight against heresy. That of course raises the question of how the ecclesiasti- cal authorities coped with reports or accusations of deviant religious beliefs or practices (whether true or false)2 before inquisition came onto the scene. We have seen some of the methods used in the previous chapters, but I want to mention particularly the process of purgation, which was set forth in the decre- tal Ad abolendam issued by Pope Lucius iii at the Council of Verona in 1184. He decreed that anyone clearly taken in heresy was to be handed over to the secu- lar authorities to be duly punished, unless he abjured, and the same was true of one who was found to be heretical by suspicion alone, unless he could demon- strate his innocence by suitable purgation.3 The process of purgation consisted 1 Dizionario storico dell’Inquisizione, ed. -

The Influence of Pope Innocent Iii on Spiritual and Clerical Renewal in the Catholic Church During Thirteenth Century South Western Europe

University of South Africa ETD Laing, R.S.A. (2012) THE INFLUENCE OF POPE INNOCENT III ON SPIRITUAL AND CLERICAL RENEWAL IN THE CATHOLIC CHURCH DURING THIRTEENTH CENTURY SOUTH WESTERN EUROPE BY R.S.A. LAING University of South Africa ETD Laing, R.S.A. (2012) THE INFLUENCE OF POPE INNOCENT III ON SPIRITUAL AND CLERICAL RENEWAL IN THE CATHOLIC CHURCH DURING THIRTEENTH CENTURY SOUTH WESTERN EUROPE by RALPH STEVEN AMBROSE LAING submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF THEOLOGY in the subject of CHURCH HISTORY at the UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH AFRICA SUPERVISOR: PROF. M. MADISE OCTOBER 2011 (Student No.: 3156 709 6) University of South Africa ETD Laing, R.S.A. (2012) Declaration on Plagiarism I declare that: The Influence of Pope Innocent III on Spiritual and Clerical Renewal in the Catholic Church during Thirteenth Century South Western Europe is my own work and that all the sources that I have used or quoted have been indicated and acknowledged by means of complete references. ………………………………. ………………………………. R.S.A. Laing Date (i) University of South Africa ETD Laing, R.S.A. (2012) Acknowledgements I would like to thank those who helped me make this work possible. In particular I wish to thank Almighty God, my parents Ambrose and Theresa Laing, my siblings, especially Janine Laing, Tristan Bailey, Fr. Phillip Vietri, Prof. M Madise, Prof. P.H. Gundani, Roland Bhana, Bernard Hutton, Ajay Sam, Rajen Navsaria, Helena Glanville, Anastacia Tommy, Paulsha January and Jackalyn Abrahams. This work is dedicated to my parents Ambrose and Theresa Laing for their love and support throughout my life.